By Richard Leisenring Jr., with images and artifacts from the author’s collection

With the surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army in April 1865, many Union volunteers from Brooklyn, N.Y, were finally heading home. Shortly after, the city’s mayor, Alfred M. Wood, proposed that a medal should be designed and presented to the honorably discharged boys in blue in recognition of their sacrifice. The medals would be awarded during an appropriate ceremony.

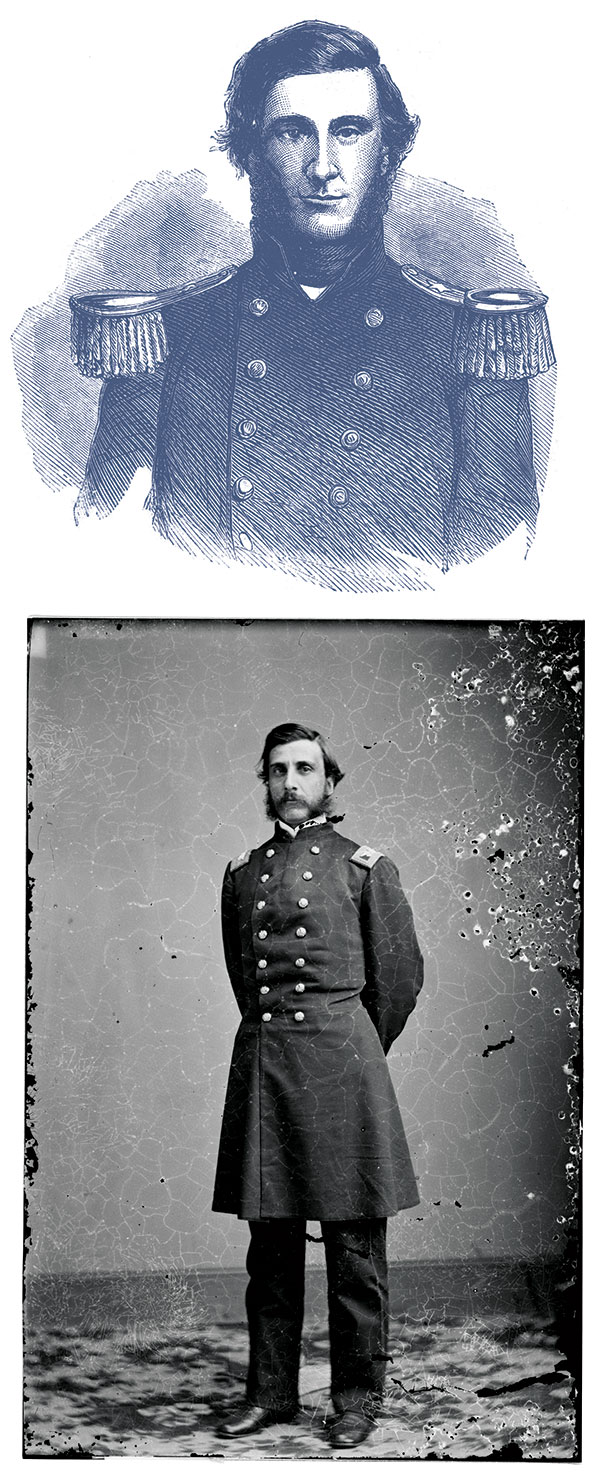

Wood, having experienced war first hand as a soldier and seeing its cost, made it a goal to recognize his comrades in a meaningful way. He had served as colonel of the 14th New York State Militia, popularly known as the 14th Brooklyn, during the Battle of Bull Run in 1861. Wood suffered a serious leg wound during the engagement and fell into enemy hands. After a formal exchange in February 1862 and discharge from the service, he and other prisoners of war returned to a hero’s welcome in Brooklyn. Wood ran successfully for mayor in the fall of 1863 and served a two-year term, choosing to retire rather than seek reelection.

Wood’s proposal was accepted by the Common Council of the City of Brooklyn on June 26, 1865, making the service medal one of, if not, the first such award authorized by a governmental body in the United States for the Civil War. New York State followed shortly after with its own medal, quietly issued on a limited basis. The Federal government lagged far behind with a similar recognition in 1905.

Brooklyn officials hastily organized a grand Fourth of July welcome parade for the few who had returned from the battlefields in Virginia. According to plan, after the parade these veterans would receive certificates redeemable for the medal when ready. But the event did not go as planned due to a breakdown in communications. Much to Wood’s embarrassment, the veterans were dismissed after the parade and were not present at the scheduled presentation ceremony that followed.

To make up for the mishap, plans were immediately put into motion to create a more formal event worthy of the moment. The city allocated $10,000 to cover expenses.

Wood’s mayoral term ended on Dec. 31, 1865, and his successor, Samuel Booth, assumed office. The former mayor used his political clout to nudge Booth to turn over the medal creation and ceremony to the Committee on War and Military Affairs. The committee decided to hold the event on Oct. 25, 1866, which allowed them enough time to complete the work and to enable the attendance of all of Brooklyn’s war veterans.

Planning the grand event

The event would consist of a military parade, presentation ceremony and a meal specifically for the veterans. It would also coincide with the dedication of the new military parade ground at Prospect Park, in the heart of Brooklyn. Special invited guests included the Empire State’s Republican governor, Reuben E. Fenton, and the two senior most officers of the U.S. Army and Navy: Lt. Gen. U. S. Grant and Rear Adm. David Farragut.

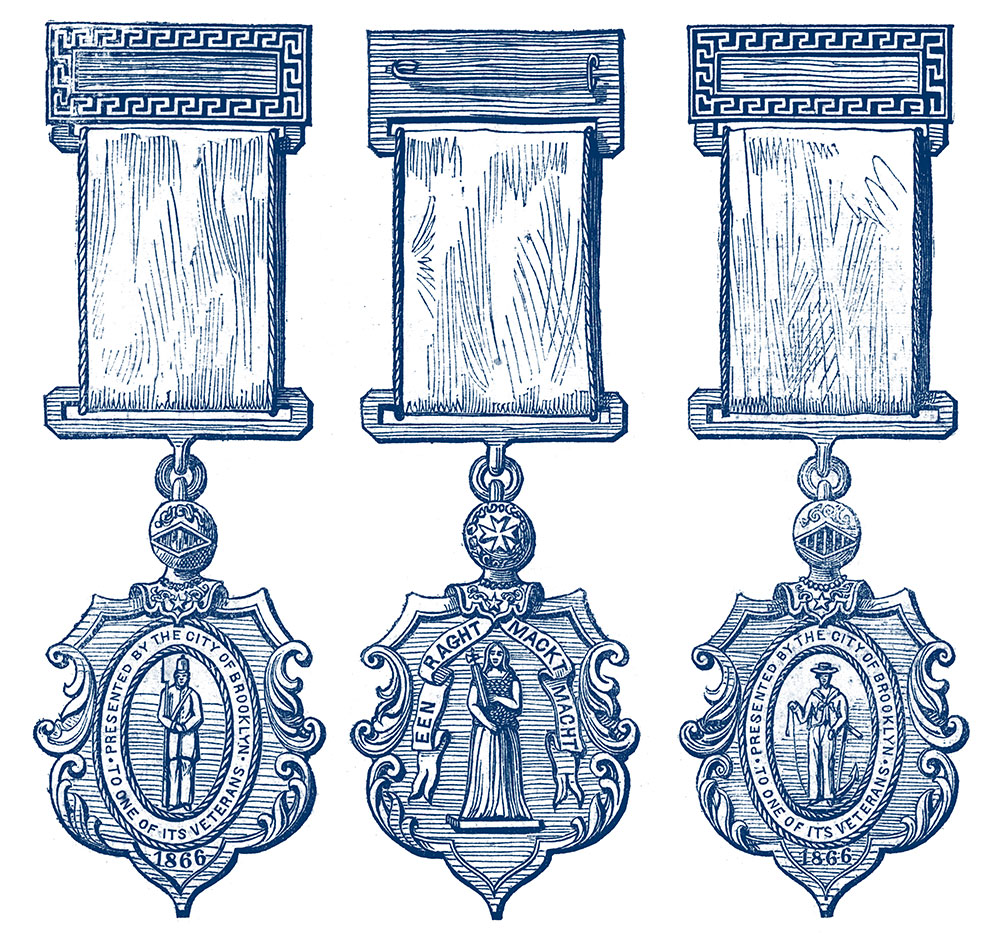

Meanwhile, design and production continued for the army and navy medals. A combined total of 6,000 bronze medals were contracted at a cost of $8,750, including the dies. Two solid gold versions for Grant and Farragut were produced for an additional $200.

The medal design consisted of a shield-shaped planchet with a soldier or sailor on the obverse surrounded by the words, “Presented by the City of Brooklyn to one of its veterans,” and the 1866 date. The reverse featured Brooklyn’s city seal. The medal was suspended from a dark blue satin ribbon attached to a rectangular bronze brooch.

The Committee also established eligibility requirements. Any soldier or sailor who resided in Brooklyn or Kings County at their time of enlistment and served honorably during the war would receive a medal. A second qualification allowed for veterans that served honorably in a unit raised in or accredited to the city or county. Provisions were also made for those that had died during their service, and allowed for their next of kin to receive a medal. As Brooklyn had been credited with having furnished 20,000 men, the Committee emphasized that only those that had actually served in the field or at sea qualified, which trimmed the numbers.

The Committee launched a massive campaign to inform veterans in area newspapers between Oct. 11-25, 1866. The notice instructed them to go with their proof of service to Room No. 1 in City Hall during evenings to register. To simplify the process, the notice encouraged officers of qualifying units to submit a list of men under their former command they deemed entitled, and urged comrades to contact their commanding officers.

Simultaneously, the Committee met with former commanders to ensure the event would be conducted in organized military fashion. On October 23, an order of procession with starting times and locations for the parade was released to the public. Two days later, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle published a “Roll of Honor” featuring a list of 4,000 veterans, 108 of them sailors.

One significant change occurred at this time. The Committee changed the location from Prospect Park, construction of which had fallen behind schedule, to Fort Greene, also known as Washington Park. Workers scrambled to build a 40-by-60-foot reviewing stand, and large tables for a lunch for the veterans, which would precede the ceremony.

The parade and ceremony unfold

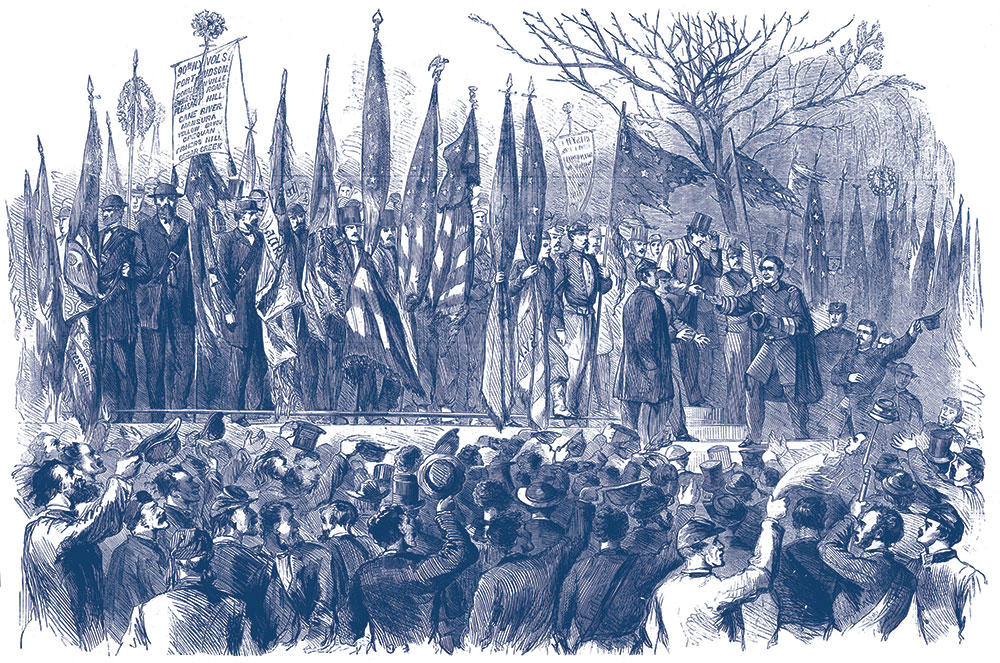

The event got underway on October 25. “Early in the day the veterans and members of the militia regiments were on their way to the various places of assemblage, the blue and the grey—not the dirty grey of the Confeds—showing handsomely as the men gathered,” reported The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “Then came the noise of drums and fife, the fluttering of the colors, the pleasant greetings of old comrades who had fought side by side through many a terrible battle, and shared rations and blankets many a time. Scarred faces, mutilated limbs, and withal the wonted movements of the old soldier, asserted that no merely holiday troops were to parade for their own gratification, but that ‘The Old Guard’ were to receive the honors to which they are so justly entitled.”

The 4,000 veterans organized in 10 regiments, and Navy veterans prepared for the first of many marches that continued into the 20th century.

Carriages full of dignitaries led the procession down Fulton Street, including Gov. Fenton, local politicians, military brass and a contingent of disabled veterans. Two companies of the city’s 7th Cavalry followed, and in their wake came Brig. Gen. Abram Duryée, commander of the Zouaves of the 5th New York Infantry, and his entourage. Another carriage of dignitaries and a platoon of police trailed Duryée. Then came the honored veterans, marching against a backdrop of Stars and Stripes that floated from buildings and waved by grateful throngs of spectators. Upon arrival, the veterans occupied positions around the reviewing stand with their regimental colors placed on the platform.

Grant did not attend and sent his regrets. Farragut did though, and spoke briefly.

Several dignitaries addressed the audience, including Gov. Fenton and former Mayor Wood.

Wood recalled the courageous volunteers who left home in 1861, the losses of so many good men on faraway battlefields, the support from the home front, and the triumph over enemies of the Constitution. “Wrong has always perished, will always perish, and the more enormous the guilt the more certain the punishment,” he noted. “The rights of men cannot be betrayed and betrayer escape; so with the Rebellion. It’s dark history is finished; it has been ground to atoms; treason has become odious; but all that went forth from this goodly city did not perish on the field of carnage or in the rebel prisons.”

Wood concluded his address by describing how the loyal patriots of Brooklyn welcomed home their boys in blue with open arms, and expressed gratitude for their service. “But Brooklyn was not satisfied, though the soldiers felt that she had done all that the fullest gratitude or patriotism required,” Wood observed. “She felt, that grand old city that she is, that something else remained to be done, and she resolved to give each soldier some tangible token of her appreciation of his valor; that each one should have a memento to be preserved and handed down from father to son.”

After concluding his remarks, Mayor Booth led the veterans and spectators (press reports estimated the crowd ranged from 15,000 to 50,000) in a rousing version of “We’ll rally round the flags, boys.” And then, the presentation of medals commenced. To streamline the ceremony, Mayor Booth and Wood presented each representative of the various organized groups with the required number medals to be distributed amongst their members. Those veterans present who were not represented by a group were called by name and handed their medals.

With all of the medals presented, the men were dismissed and treated to a lunch of sandwiches and lager beer. The dignitaries enjoyed an invitation-only dinner that evening.

Some criticism of the festivities appeared after in newspapers, which claimed the event was politically motivated, as Wood was a Democrat and Booth a Republican. Disgruntled veterans who did not register in time for the medal also complained. To make up for the latter, officials opened an office in city hall for veterans claiming the medals. Although 6,000 remaining medals were distributed, the additional claims outnumbered the medals on hand, and the city ordered an additional 1,137 medals to fulfill the requests. A grand total of 7,237 medals were issued.

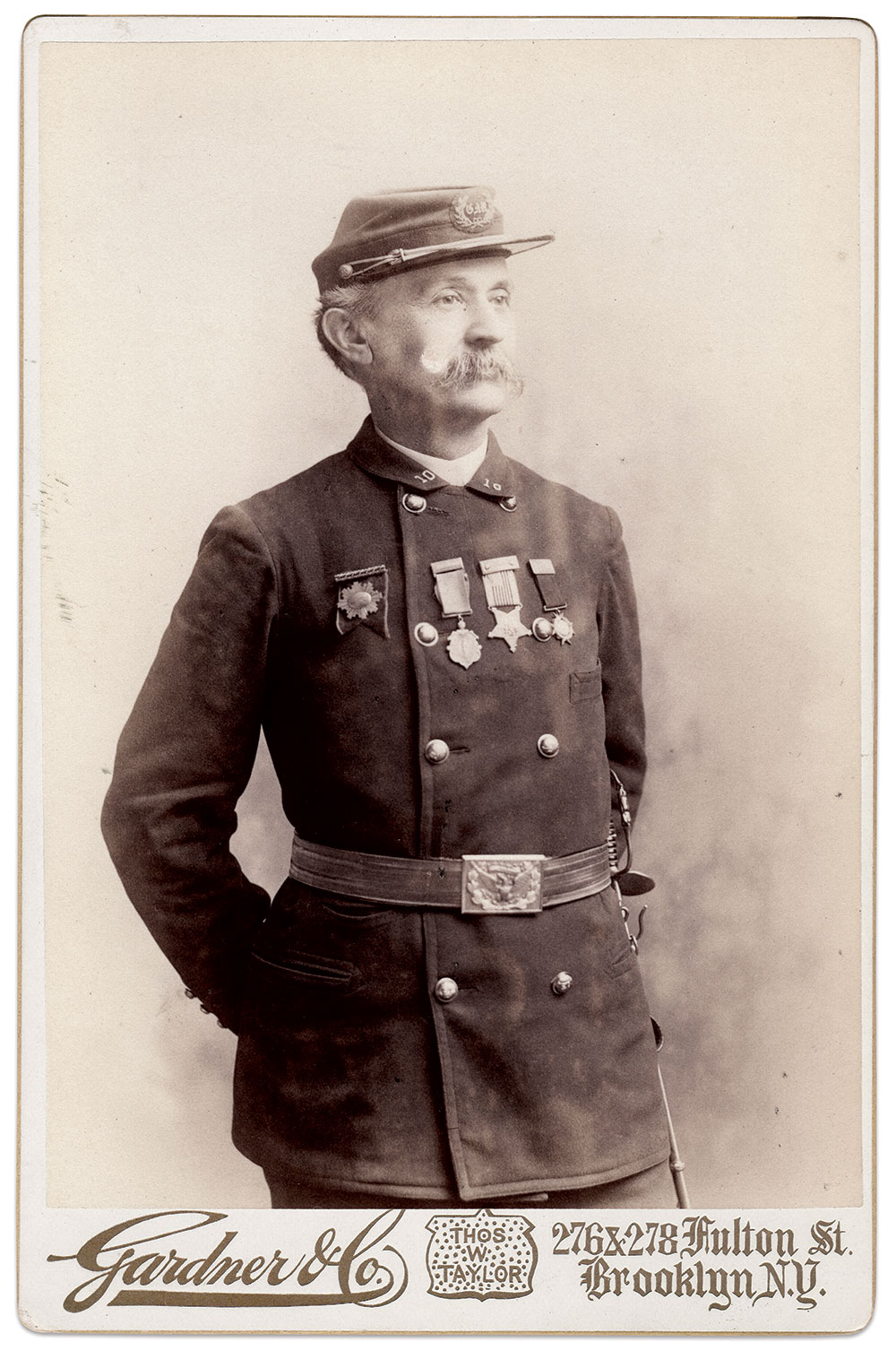

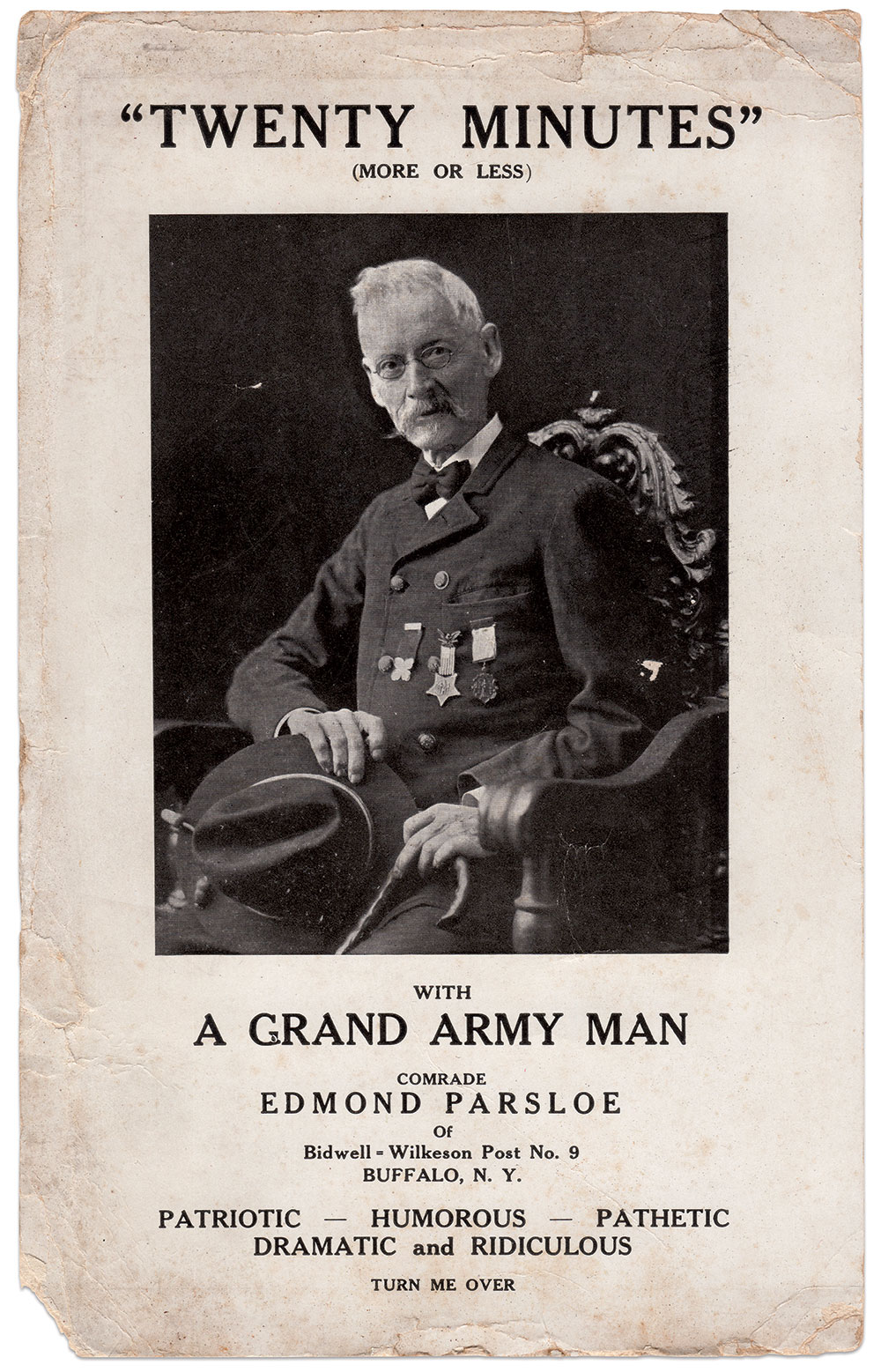

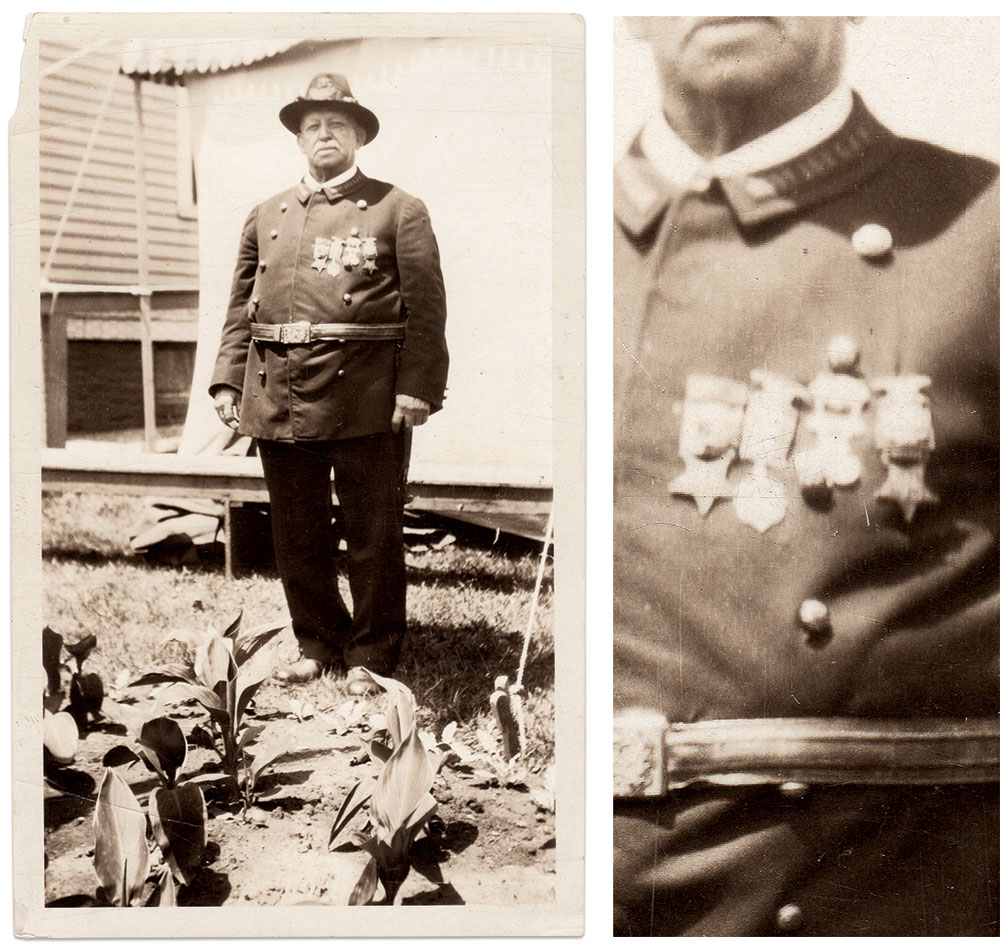

Surviving photographs in various formats taken over the following decades show the recipients proudly wearing their medals, and suggest they cherished these tokens of respect and honor. The ribbons, notoriously fragile, did not hold up well. Wearers replaced them with a variety of other ribbons and brooches, which is evident in surviving images.

References: The Brooklyn Daily Eagle; Manual of the Common Council of the City of Brooklyn, 1866; The Brooklyn Daily Union, Oct. 25, 1866.

Richard Leisenring Jr, a MI Contributing Editor, is writing an in-depth history of the Brooklyn Service medal and would like to hear from anyone who has named medals or photos of veterans wearing it.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.