By Ronald S. Coddington with images from the Rick Carlile Collection

One Sunday evening during the summer of 1863 in Alabama, Union officers gathered beside a clear spring near Bridgeport, not far from the tent of their commander. This band of brothers, together since the first weeks of the war, had experienced the ferocity of combat, grueling marches, and the rigors of life in camp—forming bonds that even death could never break.

But the Union Army had transferred their beloved leader to a new command. To mark their time together, they presented him with a token of their affection and appreciation.

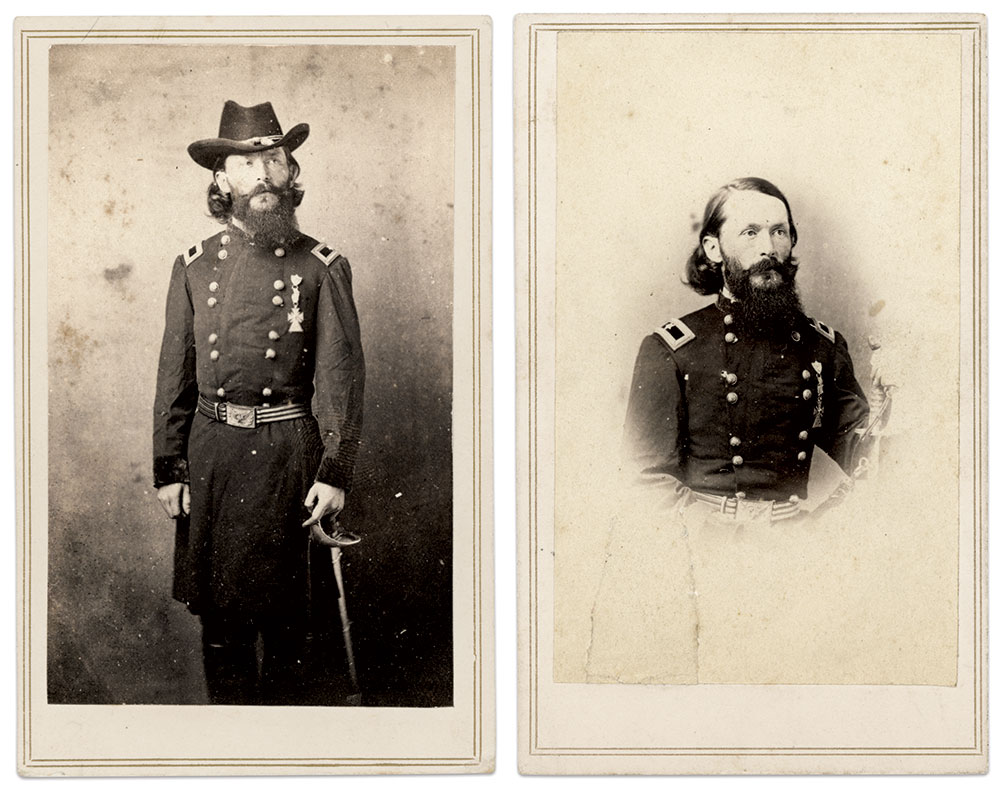

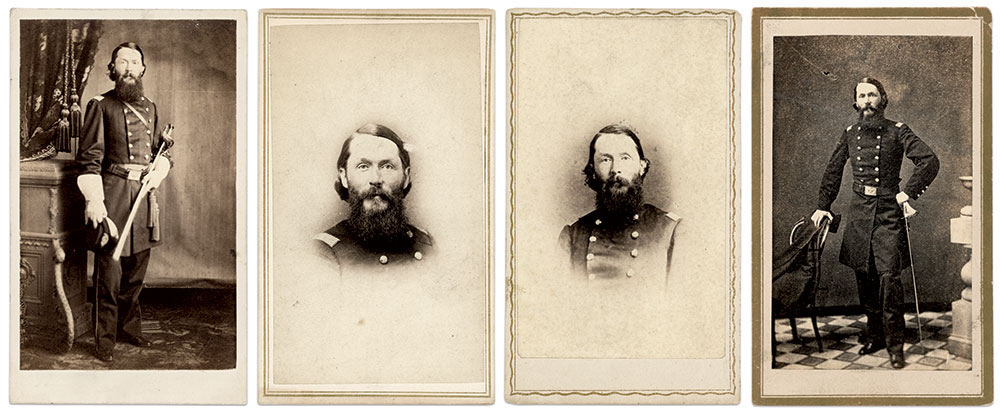

The humble ceremony, organized by the predominantly Irish Catholic officers of the 10th Ohio Infantry, paid tribute to Brig. Gen. William Haines Lytle. The regiment’s lieutenant colonel, William M. Ward, presented Lytle with a custom gold medal featuring a Maltese cross set with emeralds and diamonds and engraved with an Irish shamrock and inscriptions. Ward shared appropriate remarks for the occasion, and pinned the jeweled decoration to Lytle’s coat.

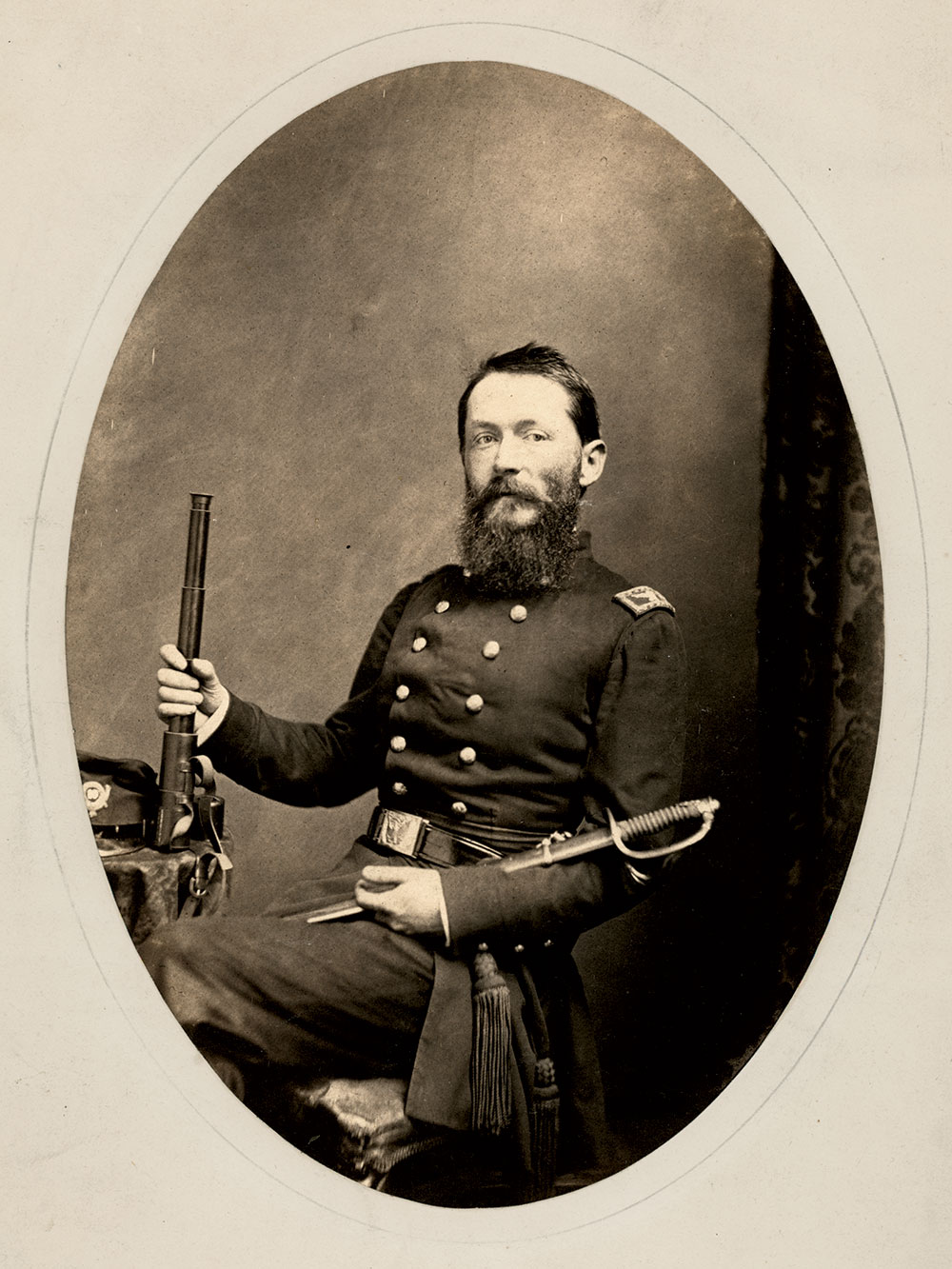

Lytle, clearly moved, replied. Standing in front of his comrades, his six-foot frame with brown hair touched with an auburn hue, and a redder beard and mustache, captivated his audience with emotional warmth, intellectual eloquence, and other oratorical gifts.

He spoke with heartfelt appreciation to the Buckeye boys and other Midwestern men who ranged from the prairies of Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin to the Great Lakes. He recalled the battles into which they marched shoulder to shoulder and earned the nom de guerre “Bloody Tenth” for sacrifices to preserve the Union.

He ended his acceptance speech with words of hope and optimism: “That the day of ultimate triumph for the Union arms, sooner or later, will come, I do not doubt, for I have faith in the courage, the wisdom, and the justice of the people. It may not be for all of us here to-day to listen to the chants that greet the victor, nor to hear the bells ring out the new nuptials of the States. But those who do survive can tell, at least, to the people, how their old comrades, whether in the skirmish or the charge, before the rifle-pit or the redan, died with their harness on, in the great war for the Union and Liberty.”

It was a day forever remembered by those who were there. One admirer compared Lytle’s speech to President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Ask No One to Live or Die for You

Lytle’s natural abilities surfaced early in life. His family tree, rooted in Ireland, branched out to America and spread from East to West. Each generation flourished, distinguished by leaders in military and civil society, carrying forward the promise of a better life, passing along an inheritance of duty and service. His father, Robert, had made his reputation in Cincinnati as a lawyer and a Jacksonian Democrat in the U.S. Congress.

By the time Lytle came into the world in 1826, the family name was well-established in Southern Ohio and Northern Kentucky. The early and untimely death of his father in 1839, when Lytle was 13 years old, cast a pall over his youth but did not slow him down: law studies at Cincinnati College, founded by his grandfather; captain of a company during the Mexican War; successful legal practice; militia general; two terms in the Ohio legislature on the Democratic ticket; a bid for lieutenant governor of the Buckeye state that fell short by 1,925 votes to Republican challenger Martin Welker, who joined the new governor-elect, Salmon P. Chase, in Columbus.

Now 31 and in the prime of life, an admirer described him: “Lytle had in him a steady fire of energy which kept him always active. There was nothing eccentric about him, nothing hesitating or despondent. Though of the so-called ‘poetic temperament,’ he did not affect peculiar sensibilities, indulge unruly passions, or exact tribute of sentimental sympathy from his friends. He was strong and self-reliant, asking no one to live for him or to die for him.”

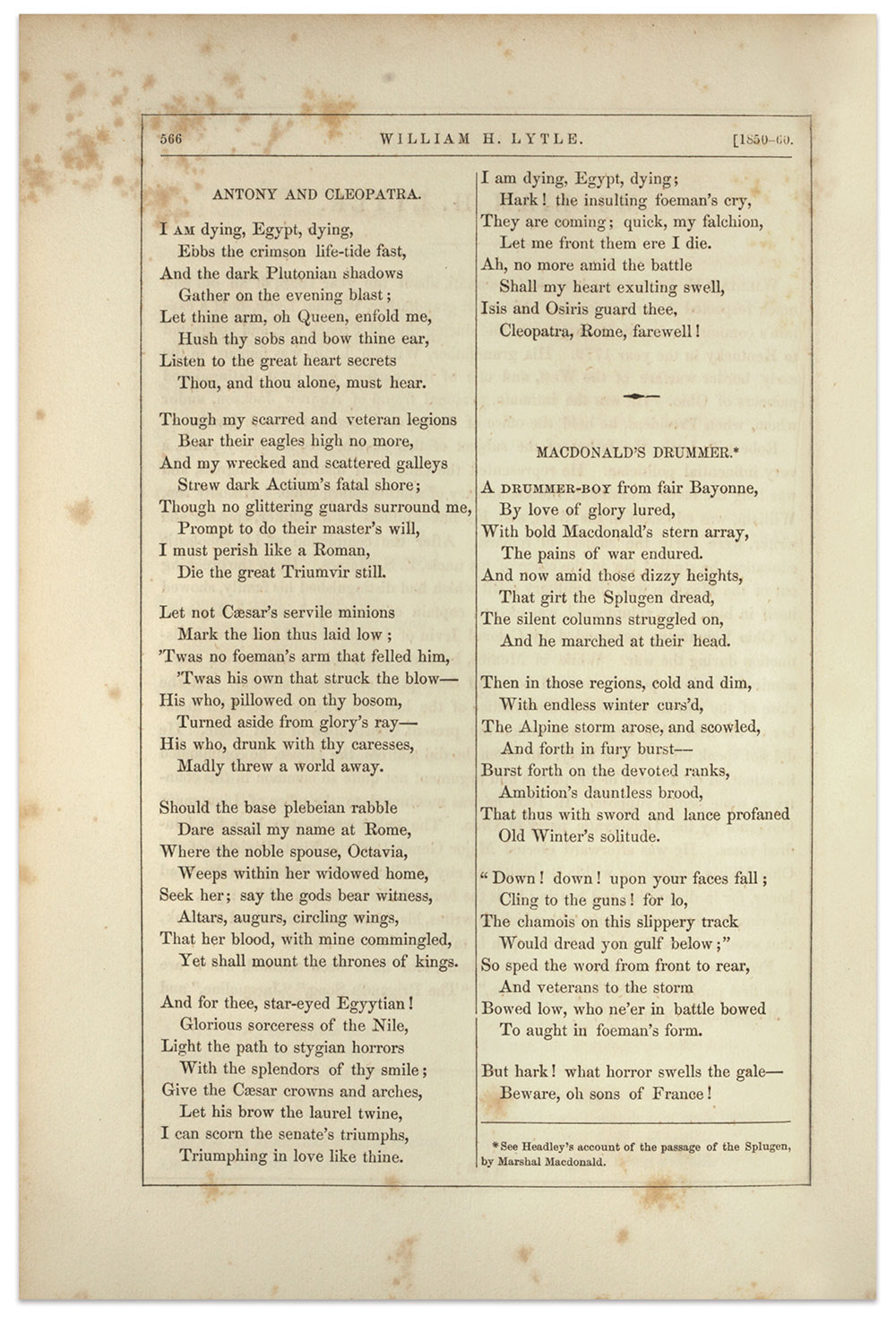

The following year, Lytle wrote a poem—one of many penned during his life. Inspired by Shakespeare’s “Antony and Cleopatra,” Lytle crafted a dramatic monologue in the voice of Mark Antony during his final moments. The memorable first line captured readers’ attention: “I am dying, Egypt, dying.”

What Lytle thought of his own effort is lost in time. According to one story, after writing the poem in July 1858, he left it on a writing table in his quarters. A friend discovered it and asked Lytle who authored it. The impressed friend, himself a poet, made a copy and carried it to the editor of the Cincinnati Commercial with a note: “The following lines from our gifted friend and talented townsman, Gen. William H. Lytle, we think constitute one of the most masterly lyrics which has ever adorned American poetry; and we predict a popularity and perpetuity for it unsurpassed by any Western production.”

Lytle’s verse enjoyed a modicum of success thanks to newspapers, a reliable source for publishing poetry, in the Midwest, South, and West. A reviewer in The Sunday Delta of New Orleans compared it to the work of literary giant Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: “It is really refreshing to turn from the cold and heavy artificiality, and the ill-adapted, second-hand Germanisms of Longfellow, to something natural, warm, vigorous and gushing, like these simply-constructed stanzas.”

Back In Cincinnati, “Antony and Cleopatra” came to the attention of William Turner Coggeshall, a journalist, publisher, and state librarian who became a bodyguard to President Lincoln. Coggeshall included Lytle as one of about 160 writers profiled in the 1860 book The Poets and Poetry of the West. Eight of Lytle’s poems made the cut.

As the storm clouds of war gathered, the poem receded into the shadows—though its classical themes of virtue, honor, sacrifice, and death echoed in the minds of many.

Clear the Way!

When war came in 1861, Lytle, in his role as a militia brigadier, flung himself into action. He executed direct orders from Gov. Chase’s successor in office, William Dennison, Jr., to mobilize troops. The days blurred into a wild kaleidoscope of activity to mold soldiers out of citizens. Then came a sword presented by the Cincinnati Bar, a majestic black charger with the Irish name Faugh-a-Ballaugh, or “Clear the Way,” and a colonel’s commission and assignment to the 10th. Regimental colors provided by the ladies of Cincinnati prompted a spirited reply from Col. Lytle: “When these wars are over, we will bring them back again to the Queen City of the West, without spot or blemish.”

Thus began the service of Lytle and his legion: The Western Virginia Campaign and first blood at Carnifex Ferry, during which Lytle suffered a wound in his left calf; brigade command along the vital rail lines of the Memphis and Chattanooga in Tennessee; charge of occupation forces at Huntsville in Alabama; and the October 1862 Battle of Perryville in Kentucky, where, while leading his men on foot to protect a compromised position, he received a shell fragment wound on the left side of his head behind the ear and fell into enemy hands.

Released on parole, Lytle waited four months to be exchanged. During this period, the War Department awarded him a brigadier’s star, and he missed the Battle of Stones River, where the 10th guarded the headquarters of Army of the Cumberland commander William S. Rosecrans.

After Lytle’s exchange came new orders to command the 1st Brigade of newly-minted Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s 3rd Division of the 20th Corps, Army of the Cumberland. With this move came separation from his beloved Buckeyes of the 10th—a bittersweet moment that led to the presentation, on Aug. 9, 1863, of the gold Maltese cross medal to remember the mutual bonds forged between a commander and his subordinates in the crucible of battle. Lytle’s acceptance stirred the souls of all present. One inspired soldier wrote a sonnet about the speech—apropos Lytle’s penchant for poetry—proclaiming: “Lead on, that we may follow, for I think the future hath not wherefrom we should shrink.”

Battle Fire

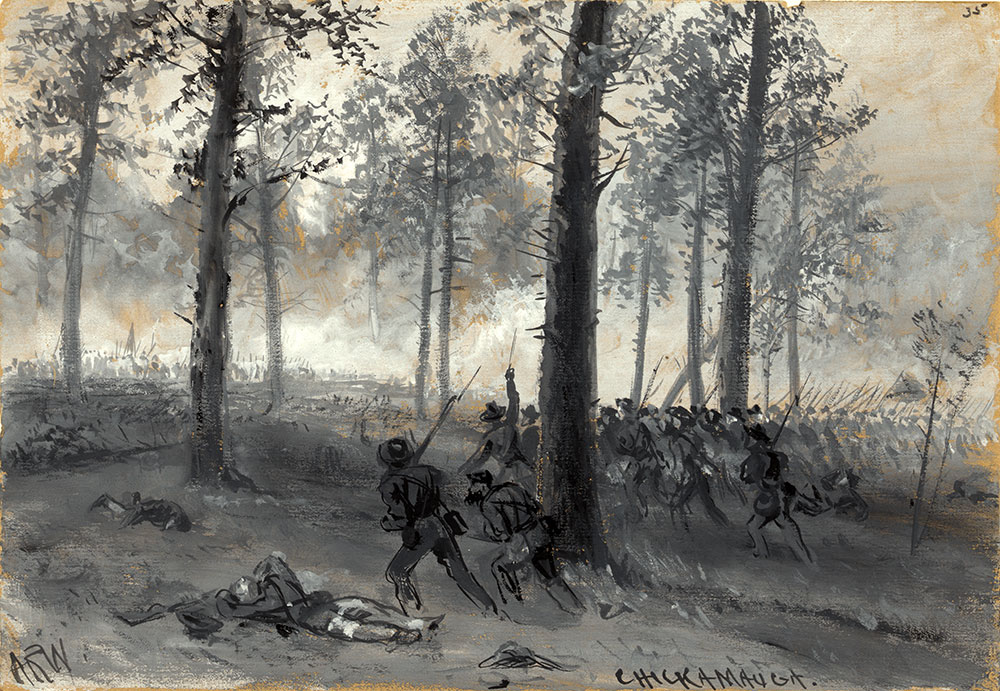

Weeks later came the Battle of Chickamauga—and Lytle’s martyrdom. There are many tellings of this story. One by fellow Cincinnatian William H. Venable pieced together eyewitness accounts by Lytle’s loyal soldiers.

According to Venable’s research, during the thick of the fray on the second day, Lytle personally led one of his regiments up the gentle slope of a hill. Gaining a foothold, the other three regiments in his brigade moved in to support the position. An artillery battery, its guns wheeled up the incline by hand, added firepower.

An aide, Capt. Alfred Pirtle, painted a word picture of Lytle: “The general is sitting on his horse at this time, facing south, his left side toward the enemy, grasping in military style his reins in his left hand; his sword drawn, the blade sloping upward, rests upon the reins. He wears high top boots, plain dark blue pants, overcoat without ornament or cape, buttoned to the throat, with sword-belt outside—the only mark of rank being the gold cord of a general on a military hat; under his overcoat he wears a single-breasted blouse with brigadier-general shoulder-straps. His horse is caparisoned as becomes his rank. Upon his face is an indescribable expression caused by what is called the ‘battle-fire’—a spirit of enthusiasm brought on by the tremendous excitement of the conflict, which irradiates every feature, sparkles from his eyes, marks with sharp outlines the curves of the nostrils, and seems ready to leap forth in words from his parted lips. I can almost see him now.”

Just yards away, Capt. Edwin B. Parsons recalled the general and his staff rode up behind the center of his regiment, the 24th Wisconsin Infantry. The horsemen stood close enough for Parsons to hear Lytle remark “Brave, brave, brave boys!” Soon after, Parsons recounted, “As I was looking into his face, a ball struck him, and seemed to me must have struck him in the face or head, for the blood flowed from his mouth. He did not fall from his horse, but one of his staff officers eased him down on the ground.”

That officer, Capt. Howard Greene, also served in the 24th Wisconsin. He recalled that Lytle had turned to give an order when hit, and he reeled in the saddle. Greene’s instincts kicked in. “I jumped from my horse, caught him by the head and shoulders, and lifted him carefully down. He recognized me as I caught him, and tried to speak.”

Greene called for two orderlies to carry Lytle out of danger, for the enemy infantry had compromised the brigade’s left flank. Lytle’s chief of staff and one of his very best friends, Col. James F. Harrison, arrived and leapt from his mount to assist. A few steps later, a bullet struck and killed one of the orderlies. Another colonel, William B. McCreery of the 21st Michigan Infantry, pitched in to help. But a bullet brought him down.

“Upon his face is an indescribable expression caused by what is called the ‘battle-fire’—a spirit of enthusiasm brought on by the tremendous excitement of the conflict.”

Meanwhile, the Confederates had broken through and soldiers from the brigade streamed by, some walking and others running, in steadily increasing numbers. Stranded, Greene recalled, “It was just at this time that Lytle opened his eyes and tried to speak, but could not. I asked him if he wished to lie down, and he nodded.”

Moments later, Lytle breathed his last. He was 36 years old.

Colonel Harrison left to do what he could to rally the troops. The other men melted away in the face of the oncoming enemy troops, now within a hundred feet of Lytle’s body. Greene, satisfying himself that the general had died, joined the retreat.

The wounded McCreery fell into enemy hands. Harrison, distraught over the loss of Lytle, eventually resigned. Greene joined Lytle in death two months later charging Missionary Ridge.

The place where the poet-warrior fell is known today as Lytle Hill.

An Unanticipated Reunion

In mid-October, three weeks after Chickamauga, a dozen Union soldiers bearing a flag of truce arrived in front of Confederate lines. They had come to recover the general’s remains. The men belonged to the 10th Ohio and were led by Lt. Col. Ward, who had presented the gold Maltese cross outside Lytle’s headquarters back in August.

This was a grim reunion, far from the one they might have imagined when they parted ways just two months ago. Ward and his Buckeyes were led to the place where Lytle had been interred. How much they learned about what had transpired between the time Greene left Lytle’s lifeless body and their arrival is not known.

Venable filled in the gap. His research revealed a connection between the Confederates credited with overrunning the Union line and killing Lytle, and the care and preservation of his body: Deas’ Brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Zachariah C. Deas.

Two Southern officers in the brigade played key roles.

Captain and assistant adjutant general Douglas West received a request from an unnamed federal officer who remained behind. He asked that Lytle’s body be protected. According to Venable, “West relates that, on hearing the name Lytle, he was thrilled, being ‘familiar with the poem which made the name immortal.’ Major West took in his keeping the general’s sword-belt and scabbard, pistol, portmonnaie, memorandum book, spurs, and even his shoulder-straps. ‘That night,’ he says, ‘in our bivouac by the camp-fire, we read the papers, letters, and scraps of poetry that we found in the pocket-book.’”

Assistant Surgeon E.W. Thomason of Dent’s Battery of Light Artillery, Venable learned, had been Lytle’s friend since the Mexican War. Thomason had the general’s remains taken to his tent, and then arranged for burial and a marked grave. Before interment, he covered the head wound with green leaves, securing them with a lace net and a finely woven cambric handkerchief. The gesture may have been intended as an act of respect and modesty, and to spare Lytle’s family and friends the sight of his injury when the body was later disinterred for return home.

Lieutenant Col. Ward and his detachment recovered Lytle’s remains and escorted them to Louisville, Ky., for transport by the mailboat Nightingale to Cincinnati. Arriving on October 21, a company of Ohio militia escorted the black coffin with silver casings to the courthouse rotunda and placed it on a dais strewn with white roses. Four sentries guarded the body while it lay in state overnight—one of them a member of the Bloody Tenth.

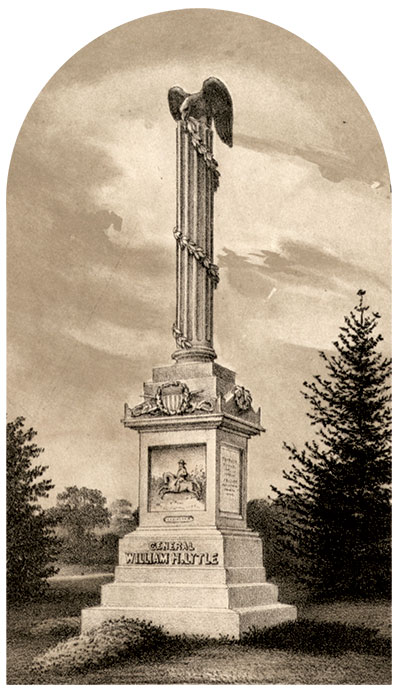

The next day, Cincinnati citizens lined city streets to witness a solemn procession that escorted the hearse pulled by six white horses with black plumes, the whole draped in mourning materials consistent with Victorian traditions. Particularly affecting were the tattered colors of the 10th, furled and festooned with crepe and ribbons. The procession took a half-hour to pass. Lytle’s remains rest in Spring Grove Cemetery, marked by an imposing monument.

Between the announcement of his death and burial, newspapers on both sides of the divided country resurrected “Antony and Cleopatra” as a fitting tribute to the general’s memory. The Chicago Tribune proclaimed Lytle “fell like a Roman.” The Cincinnati Enquirer bestowed upon Lytle the title “Bayard of the Volunteer Army” in recognition of his noble moral and martial qualities, adding, “He made it glorious with his sword, immortal with his pen!”

“Antony and Cleopatra” continued its popular life after Lytle’s death. Its heyday, from about 1875 to 1915, coincided with Blue and Gray reunions and the voluminous writings by the veterans. As the old soldiers passed from the scene, so did the poem—with modest resurgences at the beginning of World War II and during the Civil War Centennial.

References: Venable, ed., Poems of William Haines Lytle; The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Ky., July 13, 1902; The Sunday Delta, New Orleans, La., April 10, 1859; Coggeshall, The Poems and Poetry of the West; Johnston, J. Stoddard, “General W.H. Lytle and His Famous Poem ‘I Am Dying, Egypt, Dying,’” Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society (January 1914); Chicago Tribune, Oct. 14, 1863; The Cincinnati Enquirer, Oct. 14, 1863; National Archives via Fold3.com.

Ronald S. Coddington is editor and publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.