By Kurt Luther

In past columns, we often focused on identifying Civil War soldier photos. However, military images are a much broader genre, and one type of portrait that has seen relatively little attention from photo sleuths is that of the 19th century military cadet. In this column, I explore the identification process for two such cadets, with the help of community members and archives professionals, period newspapers, and genealogy resources.

This story began with a request for information in Civil War Faces, a Facebook group dedicated to the study of Civil War portraits with over 14,000 members. Sharon Karam, a postcard dealer, shared a carte de visite of an unidentified young man in uniform, likely a military cadet. Karam asked about the man’s uniform as well as the significance of a pin on his jacket. The carte had a backmark from C.A. Pugh of Blacksburg, Va.

As a professor at Virginia Tech, whose main campus is based in Blacksburg, I found my interest piqued. Virginia Tech was founded in 1872 as a land-grant university with a corps of cadets. Today, as one of only six senior military colleges in the United States, it boasts 1,200 cadets. Could this photo depict a cadet from Virginia Tech’s early years?

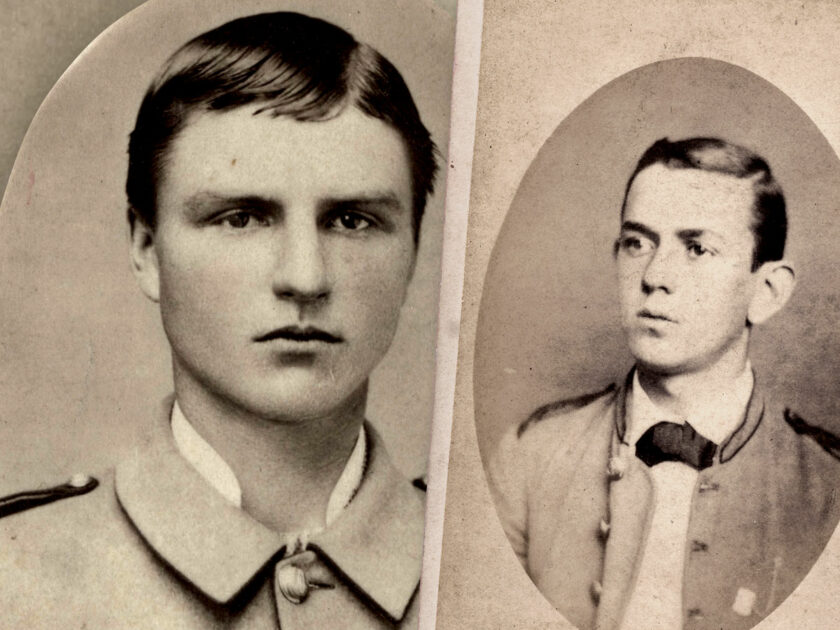

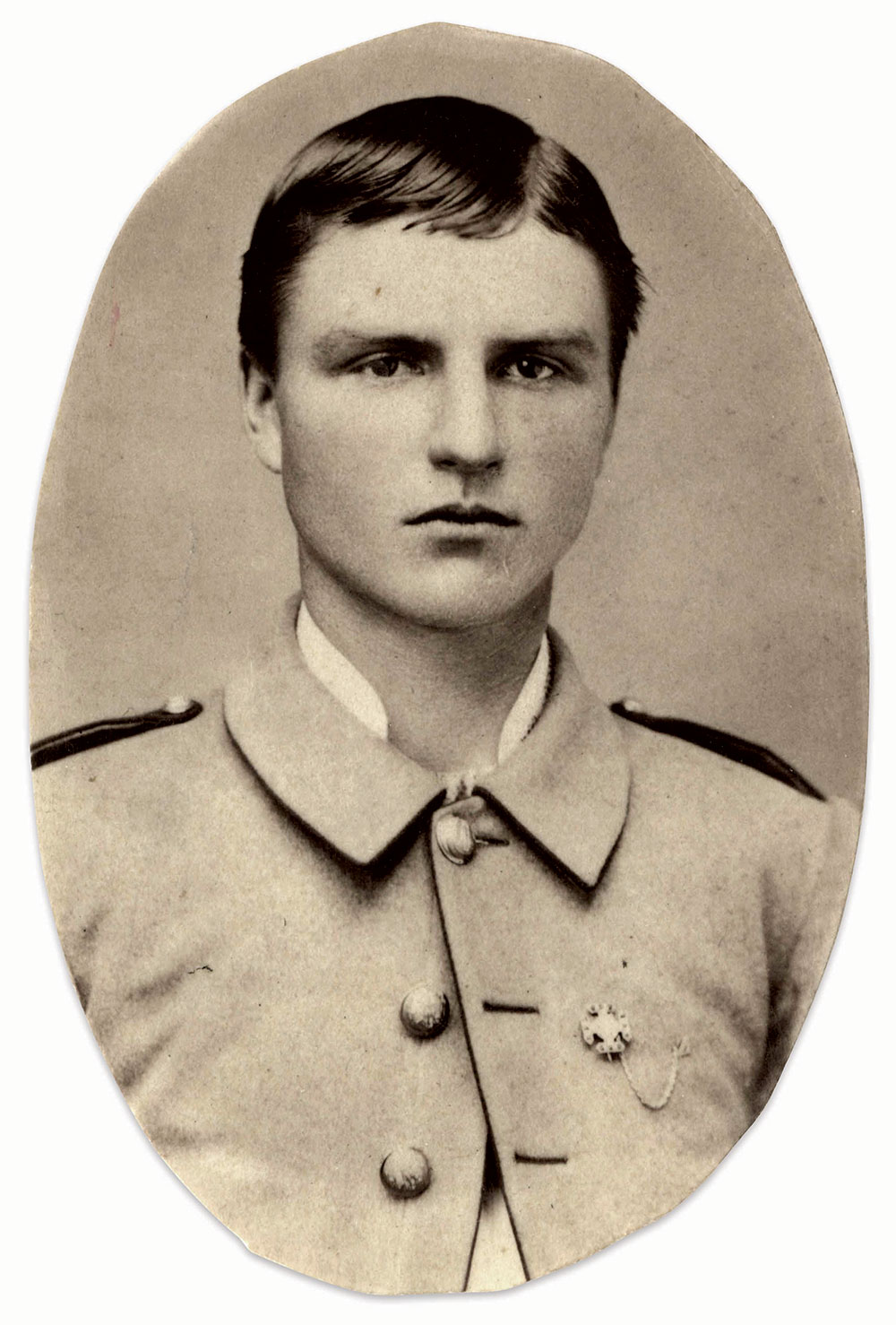

Looking closer, I saw that the photo shows a young man with carefully combed dark hair and dark eyes. He wears a light-colored military coat with the top button fastened, a pointed collar, and shoulder loops. There is a cross-shaped pin with a short chain (pin guard) affixed to his left breast. The vignette view crops out any rank insignia that might have been visible on his sleeves.

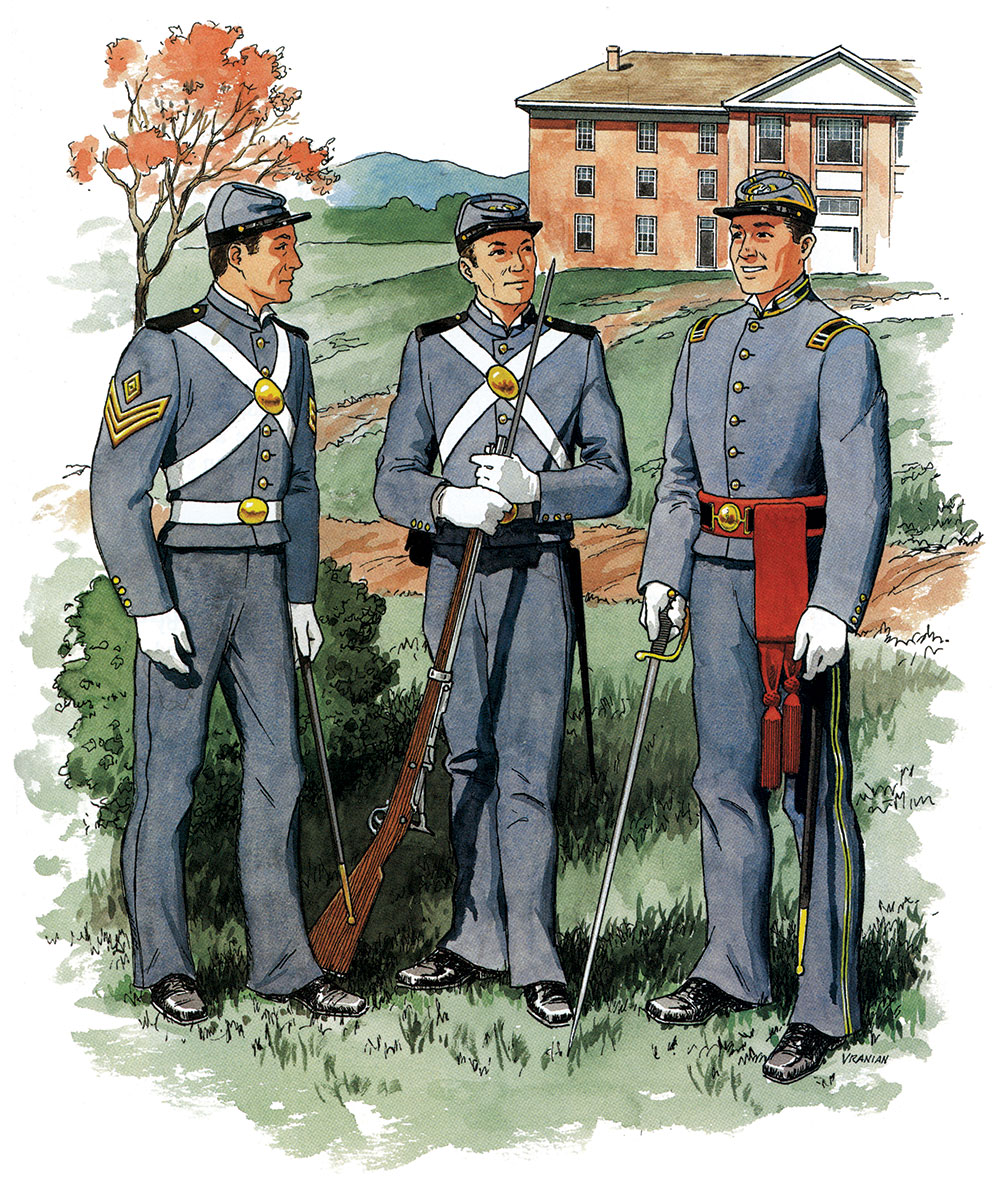

I knew from previous study of Virginia Tech cadet uniforms that their designs changed frequently over the first few decades of the university’s existence, so identifying the unknown cadet’s variant could help date the image. I consulted a book in my collection, Donning the Blue and Gray (1992) by Harry Downing Temple, which offers illustrations and descriptions of Virginia Tech cadet uniforms from the university’s founding through World War II. For the year 1881, I found what looked like a perfect match in the enlisted version of the cadet uniform. The book further notes that this design proved unpopular and, by late 1883, was replaced with a West Point-inspired coatee. Thus, the unknown cadet likely sat for this photo between 1881 and 1883.

I shared my findings with Daniel Newcomb, a collector of early Virginia Tech photos with a master’s degree in history from that university. Newcomb confirmed the photo was a Virginia Tech cadet and agreed with my theory about the uniform and dates.

With Newcomb’s help, I felt confident that the photo showed an early VT cadet, but I had no chance of identifying him without reference photos. I shared what I had found so far with Aaron Purcell, Director of Special Collections and University Archives at Virginia Tech, who connected me with his colleague John Jackson. In the archives, Jackson located an exact copy of the unknown cadet photo, and his version had a name inscribed–Gholson C. Harris. Jackson also identified the pin as indicating membership in the local Zeta chapter of Kappa Sigma Kappa, an early VT fraternity, based on contemporary examples. The date estimate from his uniform also proved correct. Jackson found another photo of Harris dated 1883, and an 1884 student newspaper article mentioned Harris returned home to Holly Springs, Miss., to study medicine. On Ancestry.com, I learned that Harris attended medical school in Louisville and died in 1929.

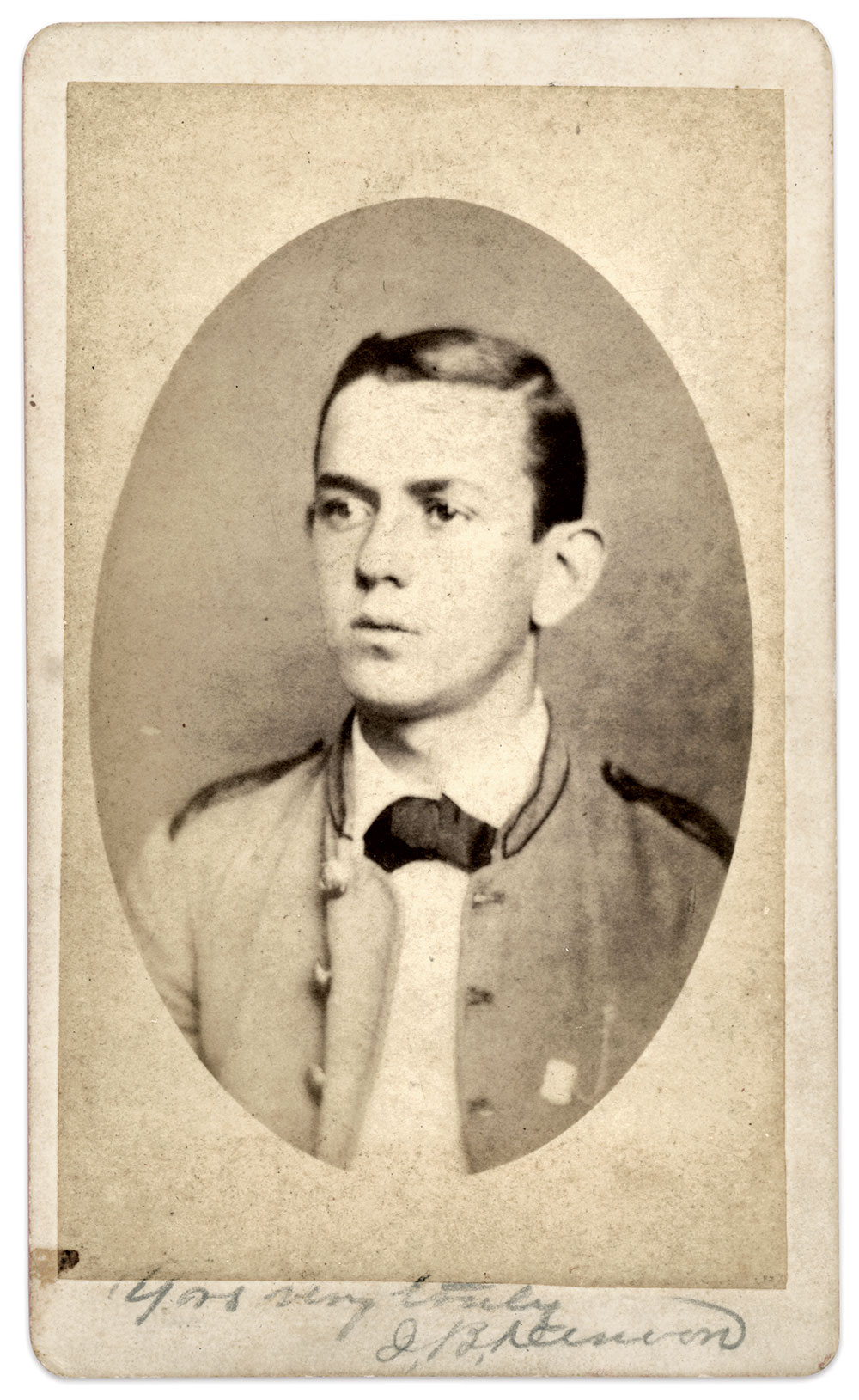

A day after posting this unknown cadet photo, Karam posted a second photo. This photo, too, was a vignetted carte de visite depicting a young man in a military uniform. He had similar coiffed dark hair and eyes, but slightly larger ears, and the style of his uniform differed from the other cadet’s. He wore an unbuttoned, light-colored jacket with a short collar and dark piping and dark-colored shoulder loops over a white collared shirt and dark cravat. He also wore a pin and guard of a different design on his left breast.

This photo also lacked a photographer’s backmark, but perhaps more promisingly, it had two inscriptions, one on each side. Both contained the penciled valediction “Yours very truly” followed by what appeared to be the cadet’s name. The first part was clearly “J.B.” or “J. Bolling,” but the cramped handwriting made it difficult to decipher the last name. Fortunately, the user who posted the photo had crowdsourced the transcription effort. Another user, Rebecca Stearns, identified the surname as “Denoon.” Better yet, she also found a possible matching profile on Find a Grave. “J. Bolling Denoon” was born in 1859, died in March 1909, and buried in Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Va.

The Find a Grave profile didn’t provide any other information about this Denoon. I wanted to learn more about him, starting with the mystery of whether he was indeed a Virginia Tech cadet. Dating the uniform and consulting Virginia Tech Special Collections and University Archives had worked well before, so I tried it again. Returning to Donning the Blue and Gray, I turned only a few pages before finding my answer. The enlisted version of the very first cadet uniform, established at the university’s founding in 1872, was a perfect match for Denoon’s attire. Temple notes that Virginia Tech’s first commandant of cadets, Brig. Gen. James Henry Lane, formerly of the Stonewall Brigade, “modelled the cadet uniform after that of the Confederate soldier.” Just to be safe, I checked the other uniforms in the book, but found no other matches. Enlisted cadets wore this uniform until 1881, when they switched to Gholson Harris’s version with the pointed collar, so the date range was about a decade wide.

I shared this information with Aaron Purcell and John Jackson in VT Special Collections and University Archives. Jackson responded with the answer I was hoping for: “Our early student index file has James B. Denoon listed as a freshman in 1876, and as a sophomore in 1877, with no further mentions.” Denoon was indeed a VT cadet within the time frame I had estimated, photographed during the first years of the university’s existence wearing the Corps’ original uniform. But what happened to him afterwards?

I ran some broad Google searches on various permutations of his first and middle names and initials. There were few results, but one for “J. Bolling Denoon” surfaced in issues of the fraternity Pi Kappa Alpha’s monthly journal, The Shield and Diamond, from 1891-92, digitized on Google Books. Denoon is listed twice as a member of the fraternity’s Epsilon chapter, established at “Virginia Agricultural [and Mechanical] College” (an early name for Virginia Tech) but marked “extinct” as of the 1890s. This clue suggests that the pin Denoon wears in his cadet portrait might represent his Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity. I found a similar-looking modern version of the pin and guard called a “President’s Badge” for sale by the fraternity’s official jeweler, Herff Jones.

Pi Kappa Alpha, founded at the University of Virginia in 1868, also has an interesting history at Virginia Tech. Its Epsilon chapter established in 1873, of which Denoon was apparently a member, was the “first social organization of any kind” at Virginia Tech, according to the university’s website. However, by 1880, the administration had turned against fraternities and passed regulations banning secret societies and associations that led to most fraternities closing–hence, Denoon’s chapter listed in the fraternity journal as “extinct” in the early 1890s. Fraternities reestablished themselves at Virginia Tech within a couple of decades, but it would be almost a century, in 1972, before Pi Kappa Alpha became one of the first two fraternities formally recognized by the university. Denoon’s Epsilon chapter is still active, though currently on a deferred suspension for hazing and other violations.

My Google searches also revealed another lead: a second Find a Grave profile, this one for “James B. Denoon.” Like the profile found by Stearns, this one showed an 1859 birth year. But unlike the other profile, this one indicated that Denoon died in 1896 and was buried in Charlotte, N.C. It seemed hard to imagine two men with variations of the same name, “James Bolling Denoon,” both born in 1859, but with different death years and location. I realized I needed to dig deeper and figure out which of these profiles, if either, described the cadet in the photo.

First, I tried to learn the source of the death year on each profile. The 1909 profile stated simply that the date of burial was March 13, 1909, and the reference was “Cemetery Records.” The 1896 profile included several snippets from obituaries published in the Charlotte Observer newspaper. The first and longest of these notes that Denoon’s death at age 36 was “totally unexpected,” though he had suffered from consumption (tuberculosis) for over a decade. According to this obituary, Denoon grew up in Richmond. Denoon and his wife, whom he married in Charleston, W. Va., ran the telephone exchange together in Charlotte and raised a young daughter. This 1896 profile does not name the wife or daughter and does not link to any parents, siblings, or other family members.

The profile also doesn’t mention Virginia Tech. A man born in Richmond in 1859 would be from the right geographic area, and the right age (about 17) to attend the university as a freshman in 1876, but I needed more hard evidence. The 1880 U.S. Census, available via Ancestry.com, shows J. Bolling Denoon, a 20-year old telegraph clerk, living in Richmond in the home of his older brother Ritchie. From J. Bolling Denoon’s 1909 Find a Grave profile, claiming he is buried in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery, we know this must be Richard Denoon (1851-1920), interred in the same family plot.

The Library of Congress’s Chronicling America digitized newspaper archive yielded two notable results in Richmond-area newspapers during the 1880s. The Dec. 5, 1880, edition of Richmond’s Daily Dispatch contained an item about a new militia company being formed in the city, with several volunteers, including one J.B. Denoon, forming a color guard. This anecdote places Denoon in Richmond following his time at Virginia Tech, and still involved in martial pursuits, but otherwise doesn’t shed much light. The militia unit that his new company would join, identified as the “First regiment,” is likely part of the Virginia Volunteers, the predecessor to the Virginia National Guard that was first authorized in 1871, and funded beginning in 1884, according to the Library of Virginia’s Adjutant General Records.

Another item in the Daily Dispatch published over four years later, on March 11, 1885, notes that “Mr. J.B. Denoon, of Richmond, who has been stationed at Charleston, W. Va., several years in charge of the Telephone exchange there, has been assigned to duty in this City.” We know from Denoon’s obituary that he married his wife in Charleston, and now we know what he was doing there. Less clear is why he returned to Richmond, but the 1896 obituary quoted in the Charlotte Observer suggests that he had come to town nine years ago, or about 1887, only a couple years after returning to Richmond.

Besides the occasional advertisement, there are few newspaper references to Denoon over that decade until October 2, 1895, when the Observer profiled “Supt. Denoon and his agreeable and expert better half,” Mrs. Denoon, the principal daytime operator. The article notes that “Mrs. Denoon is particularly skillful with ear, hand, and head, and to her is entrusted the main business of the office, while Mr. Denoon looks after the outside wires and stations.”

Sadly, the Observer’s next mention of the Denoons, less than four months later, was James’ aforementioned obituary on January 16. Subsequent notices about the funeral and burial in Charlotte’s Elmwood Cemetery followed. On January 19, a follow-up story reported that Mrs. Denoon would be returning home by February to be with her mother. “Just who will take charge of the telephone exchange,” it added, “has not been decided.”

Determining the first name of a married woman in the 19th century can be challenging, more so here because of the destroyed 1890 census records. Mrs. Denoon isn’t listed in either of James’ Find a Grave profiles, nor could I find their marriage records in West Virginia’s online database. However, she is listed in contemporary city directories as “Mrs Fanny Denoon” with the same home address as James. A Find a Grave search for that name shows that Fannie Gebhart Denoon died in 1921 in Charleston, W. Va., age 67. As the newspaper indicated, she returned home to Charleston to live with her mother, Margaret, and never remarried. The profile also lists the unnamed daughter mentioned in James’ obituary. She was Jessie Belle Denoon (1889-1970), a retired secretary who also never married. Both are buried in Charleston, but in Spring Hill Cemetery, not with James in Elmwood.

Having traced the life of James Bolling Denoon since his time as a Virginia Tech cadet, we see he lived in Richmond; Charleston, W. Va.; and Charlotte, N.C. He started a militia company, married, raised a daughter, and pursued a successful career in the telegraph / telephone industry before succumbing to tuberculosis at age 36. But one key question remains. If Denoon died in 1896 in Charlotte, why does Find a Grave suggest that he was buried in Richmond in 1909, surrounded by his parents and siblings?

The answer comes from one more Charlotte Observer article, dated March 12, 1909. It states, “The remains of Mr. J.B. Denoon, which were interred in Elmwood cemetery 13 years ago, on January 16th, 1896, were disinterred today and will be taken to Richmond, Va., this evening.” Thus, both Find a Grave profiles are substantively correct. Denoon died in 1896, but after his wife and daughter removed to West Virginia, perhaps his Richmond-based family wanted him back home.

Sharon Karam’s curiosity to learn more about the unnamed cadet in her carte launched a journey to discover his name and connection to the early years of Virginia Tech. The research techniques used to identify this 19th century military cadet are similar to sleuthing Civil War portraits, and open up new avenues to appreciating our past.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is a MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.