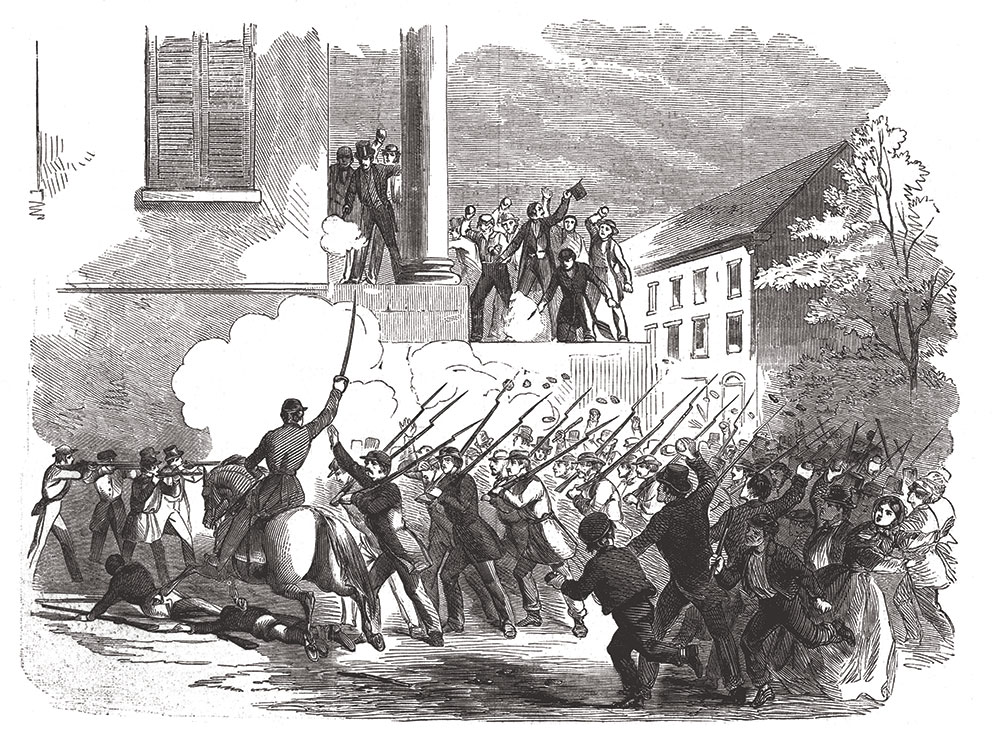

Less than a month after the bombardment of Fort Sumter inaugurated civil war, pro-secession militia in Missouri agitated to join the nascent Confederacy. When word leaked that the militia planned to raid the federal arsenal in St. Louis, where 38,000 muskets and rifles were stored, Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon and his U.S. forces, about 6,000 state volunteers and regular troops, went into action. On May 10, 1861, Lyon moved against the militiamen quartered at Camp Jackson in St. Louis and compelled the surrender of 669 of them.

As Lyon and his men marched the prisoners through the city, throngs of pro-secession citizens turned hostile, throwing stones and shouting profanity—reminiscent of the Baltimore Riot weeks earlier. Firing broke out in the streets of St. Louis, leaving 28 citizens dead and 75-90 more injured, including women and children.

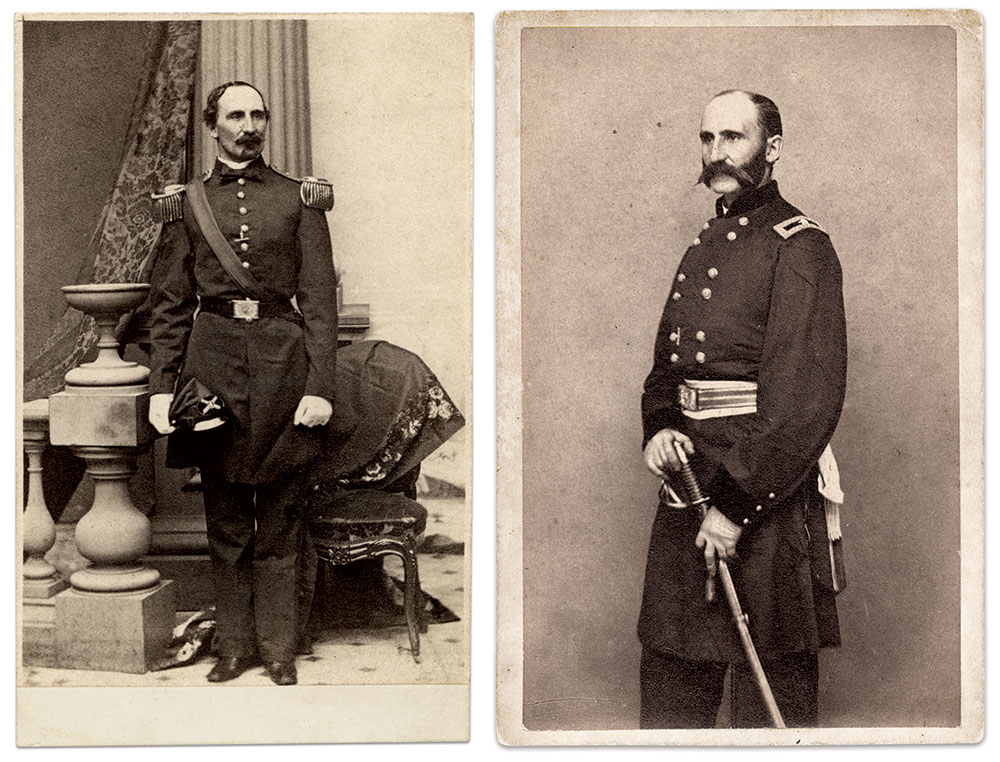

One of the Union officers in the thick of the fray was 1st Lt. Rufus Saxton of the 4th U.S. Artillery. Born into a progressive Massachusetts family, Saxton attended West Point and graduated in 1849. He spent the 1850s in operations against Florida Seminoles, on frontier duty, and as an artillery instructor at his alma mater. The army planned to send him to Europe in 1860, but threats of war prompted a change of assignment to St. Louis in early 1861.

A few months later came the attack known today as the Camp Jackson Affair.

Saxton recalled the event after the war. “I had been drilling a body of recruits, and was ordered to command them in a charge on the Confederate batteries. We set out at dawn, and realizing fully the dangers of the task we had been sent, you can imagine our feeling when instead of the storm of grape and canister we expected we were greeted by the white flag, in token of surrender. It was my duty then to escort the prisoners to the arsenal, and as we moved them off the yells of the populace and the cheers for Jeff Davis showed us the temper of the crowd. Several shots were fired at us; one just grazed my neck, another killed the sergeant at my side. I warned the crowd that I should fire if this kept up, but the taunts only grew louder. One burly ruffian seized hold of my first sergeant. My raw recruits acted splendidly, and with perfect coolness. I gave the order ‘Ready!’ And at the command ‘Aim!’ My youngsters responded in perfect time, and each man aimed low. Had I given the word to fire the slaughter must have been terrific. But there were women and children in the crowd, and just at the right moment the rioters came to their senses, and I was enabled to give the order ‘Recover arms!’ A German regiment that followed mine was not so patient, and several scattering shots from these soldiers killed about thirty persons in the crowd. When we got our prisoners in the arsenal a man named McDonald came up to me and said: ‘Captain, you are not going to be killed in this war. I fired three shots from my revolver point-blank at you, and never fazed you.’ It was one of those shots that killed my sergeant.”

Camp Jackson marked the first of many assignments given to the dependable and talented Saxton during the war. He is well remembered for defending Harpers Ferry against Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s forces in 1862—an act that resulted in the Medal of Honor—and his service as military governor of the Department of the South, in which he championed Black communities to bring men of color into the military, and helped families transition from enslavement to freedom.

Saxton remained in the U.S. Army after the war and retired in 1888. Making his home in Washington, D.C., he died in 1908 at age 83. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

In a biographical sketch of his life and service, the writer revealed a piece of advice Saxton liked to share: “To the young he would say that ‘forgetfulness of self’ should be the guiding principle of life.”

Most Hallowed Ground

is part of the Arlington National Cemetery (ANC) Project. Established by Jim Quinlan of The Excelsior Brigade, its mission is to identify all Civil War veterans on the grounds. Contact Jim at 703-307-0344.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.