60,000 Fought for the Union.

President Abraham Lincoln celebrated Maryland’s adherence to the United States in his December 1861 Annual Message to Congress. Referencing pro-secession riots in Baltimore and other anti-government acts, he observed, “Maryland was made to seem against the Union. Our soldiers were assaulted, bridges were burned, and railroads torn up within her limits, and we were many days at one time without the ability to bring a single regiment over her soil to the capital. Now her bridges and railroads are repaired and open to the Government; she already gives seven regiments to the cause of the Union.”

Union Loyal Citizens of Bel Air Helped Soldiers Isolated from Their Regiment to Safety After the Riots in Baltimore

Pro-secession rioters who attacked the 6th Massachusetts Infantry as it made its way through Baltimore on April 19, 1861, did not prevent the regiment from fulfilling its mission to protect the U.S. capital. But not all the Massachusetts men arrived in Washington. That night, 27 soldiers separated from the regiment arrived in Harford County north of Baltimore. The next morning, the Harford Light Dragoons escorted them to the Pennsylvania line. As they crossed over, the grateful soldiers offered three cheers for Maryland.

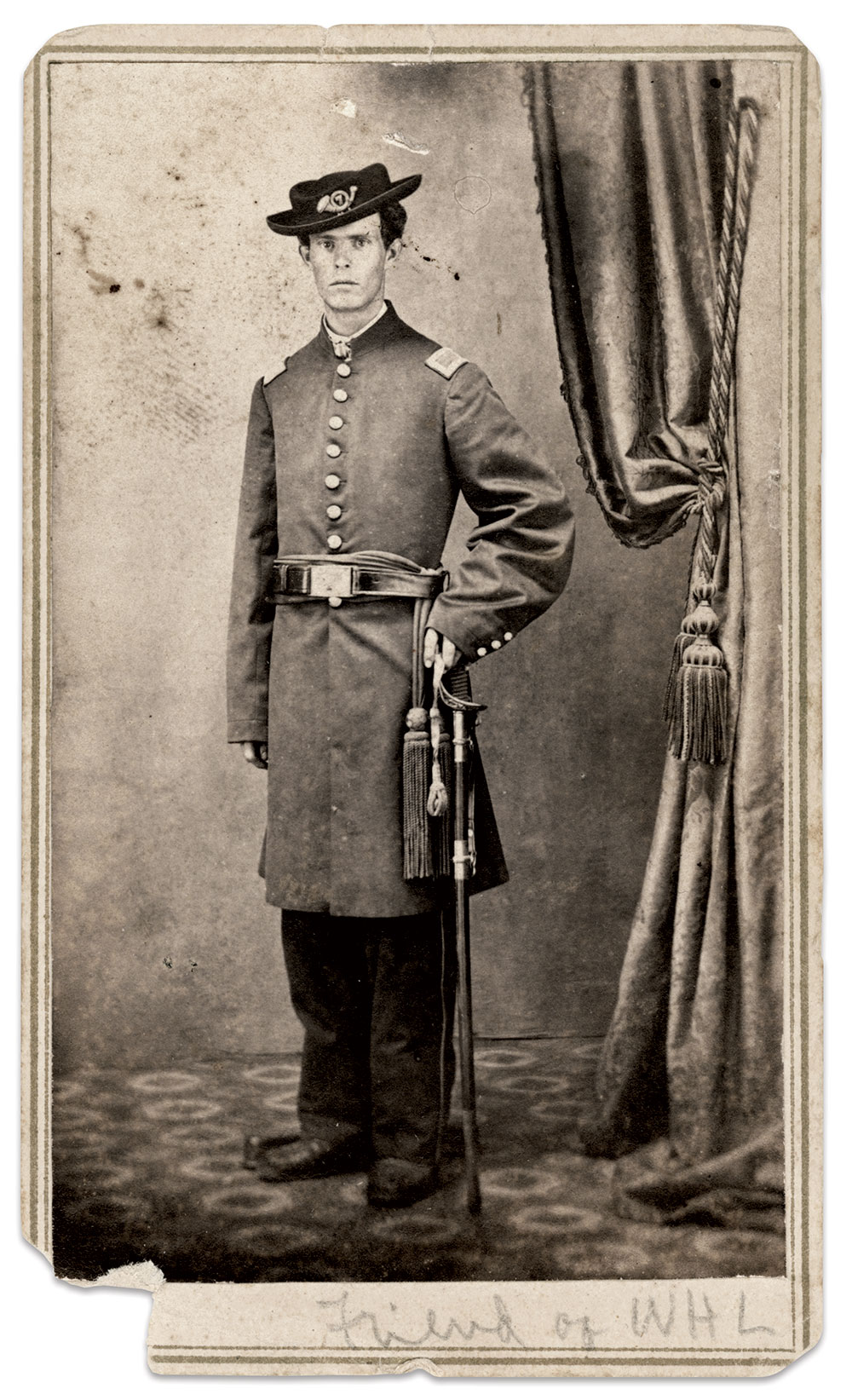

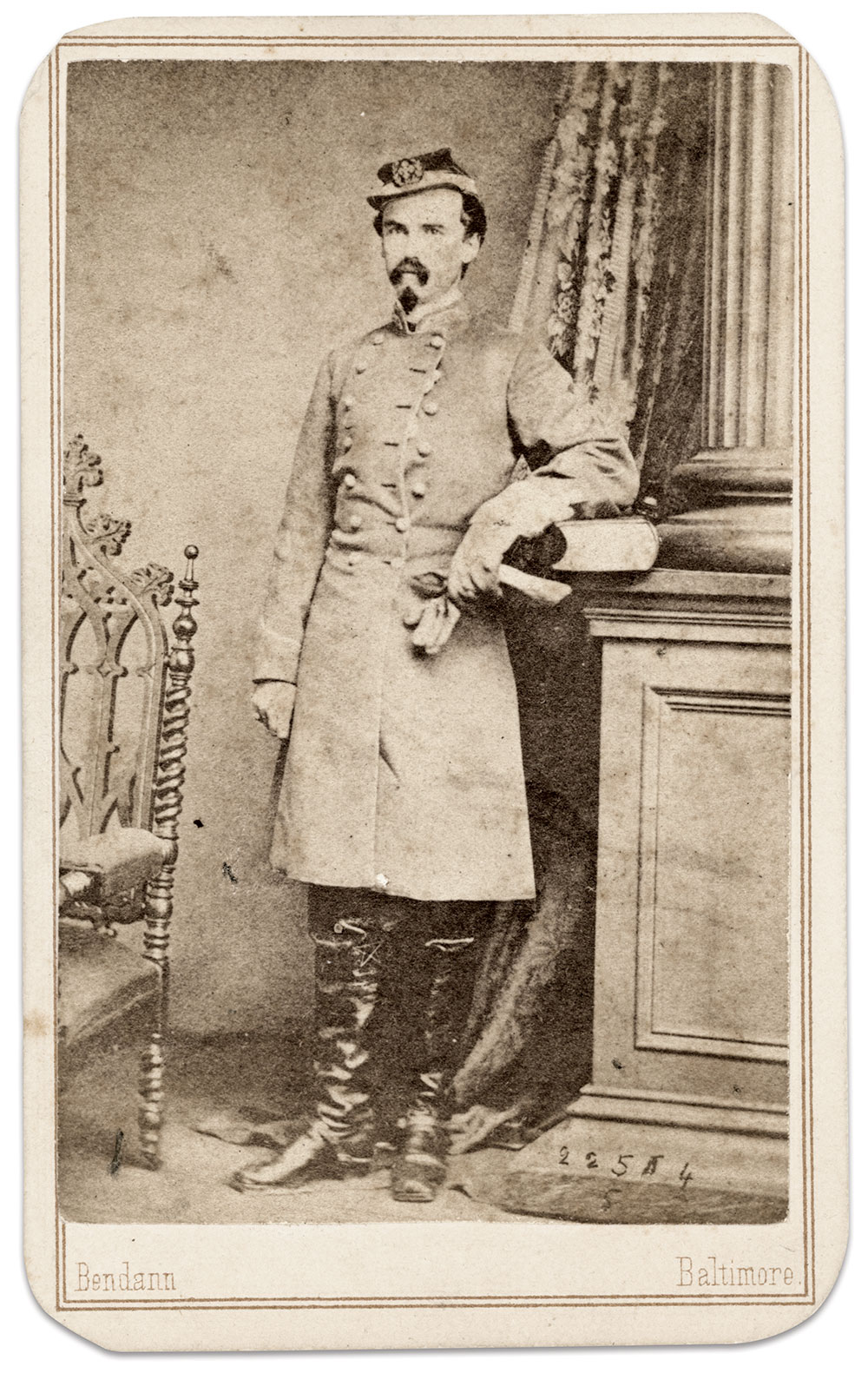

In the Harford County seat of Bel Air, National American Editor Richard Edwin Bouldin published the story. Born and raised in the town, 23-year-old Bouldin joined the 7th Maryland Infantry in 1862. Starting as second lieutenant of Company C, he rose to captain and led his command in Shenandoah Valley operations, the repulse of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, and heavy fighting during the Overland Campaign. He resigned due to poor health in late 1864.

Bouldin went on to work in the Baltimore Customs House and as postmaster of Bel Air. Active in the Maryland National Guard and the Grand Army of the Republic, he died in 1920 at age 82. His obituary noted, “the central facts of the Captain’s life centered around the civil war through which he bore himself with fidelity and ability.”

Son of the Gallant Ridgely

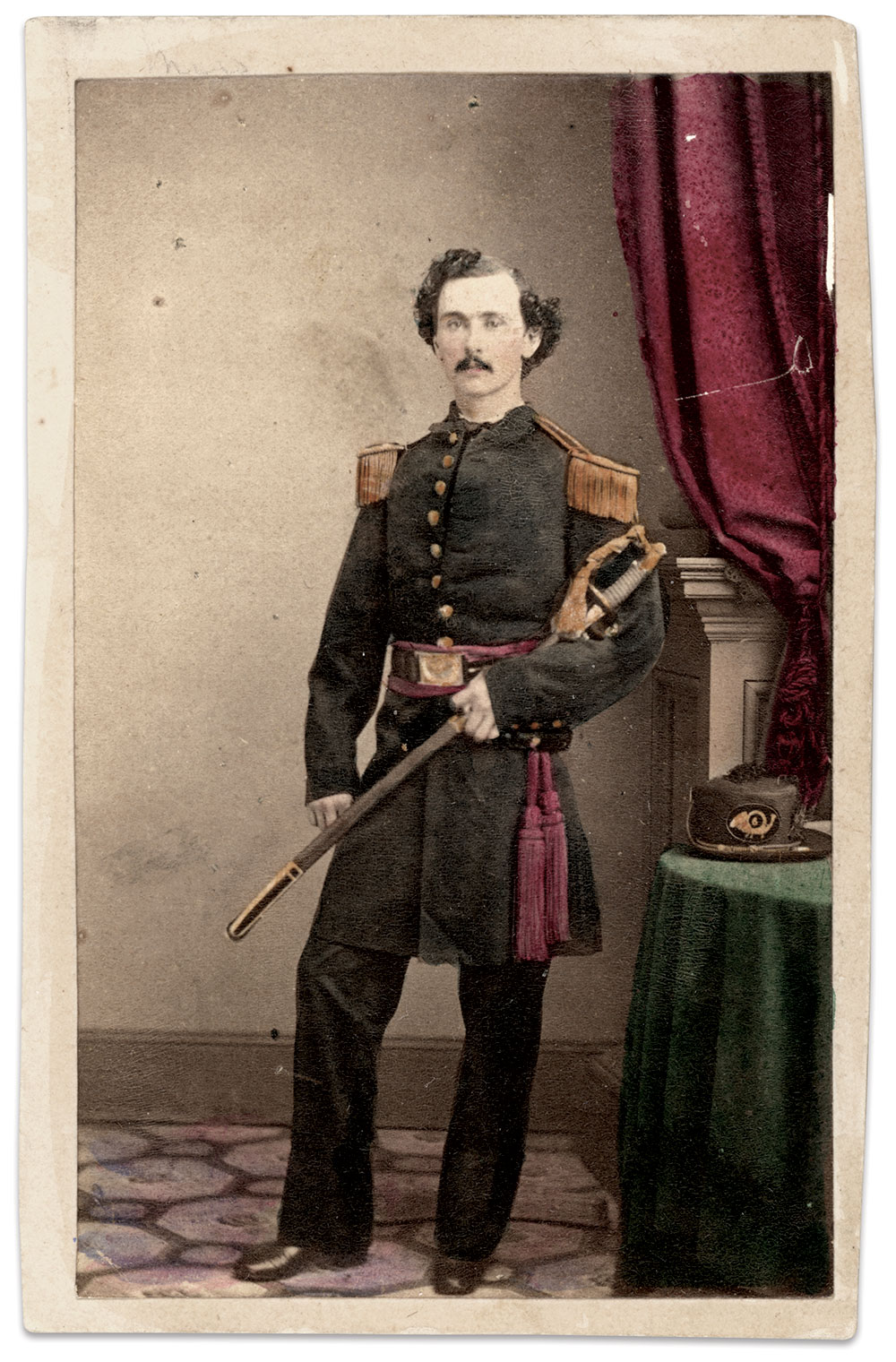

During the Mexican War, 1st Lt. Lott Henderson Ridgely of the 4th U.S. Infantry suffered a mortal wound in a fight at Galaxara Pass in 1847. Many mourned his death, including close friend Ulysses S. Grant and Brig. Gen. Joseph Lane, on whose staff Maryland-born Ridgely served. Lane adopted the dead soldier’s seven-year-old son, Franklin Lee Ridgely.

Young Franklin gained admission to the Naval Academy about 1855 but did not graduate. When the war came, he joined the army. As a second lieutenant in the 6th U.S. Infantry, he fought in the Peninsula Campaign and then resigned for his health. Ridgely settled in St. Louis, where he had family connections. Successful in business and active as a patron of music and the arts, he served as St. Louis Park Commissioner and played an important role in erecting Civil War monuments in the city’s sprawling Forest Park. Ridgely died in 1916 at age 75. His wife and two children survived him. His son, Frank Eugene Ridgely, graduated from the Naval Academy and became a commander.

He Resigned From the Naval Academy to Join the South. Then He Changed His Mind.

In April 1861, Naval Academy Cadet Yates Stirling, 18, resigned to join the Confederacy. Then he changed his mind and on May 1 wrote to Navy Secretary Gideon Welles to withdraw the resignation.

Days passed without a reply. Two of Stirling’s brothers traveled from Baltimore to Washington to plead the young man’s case to the Secretary but failed to get an audience. They left a hurriedly penned request: “I leave this note to tell you very earnestly to allow the young man whose friends are very anxious to keep him at this time under the flag of the country to withdraw the resignation considering it not sent and order him to report to the school. An early action would very much oblige myself and my brother who feel deeply on the subject of his loyalty to the country.”

It worked. Stirling spent the next 44 years in the U.S. Navy, rising in rank to rear admiral by his retirement in 1905. He died in 1929 at age 85. His remains rest in Arlington National Cemetery.

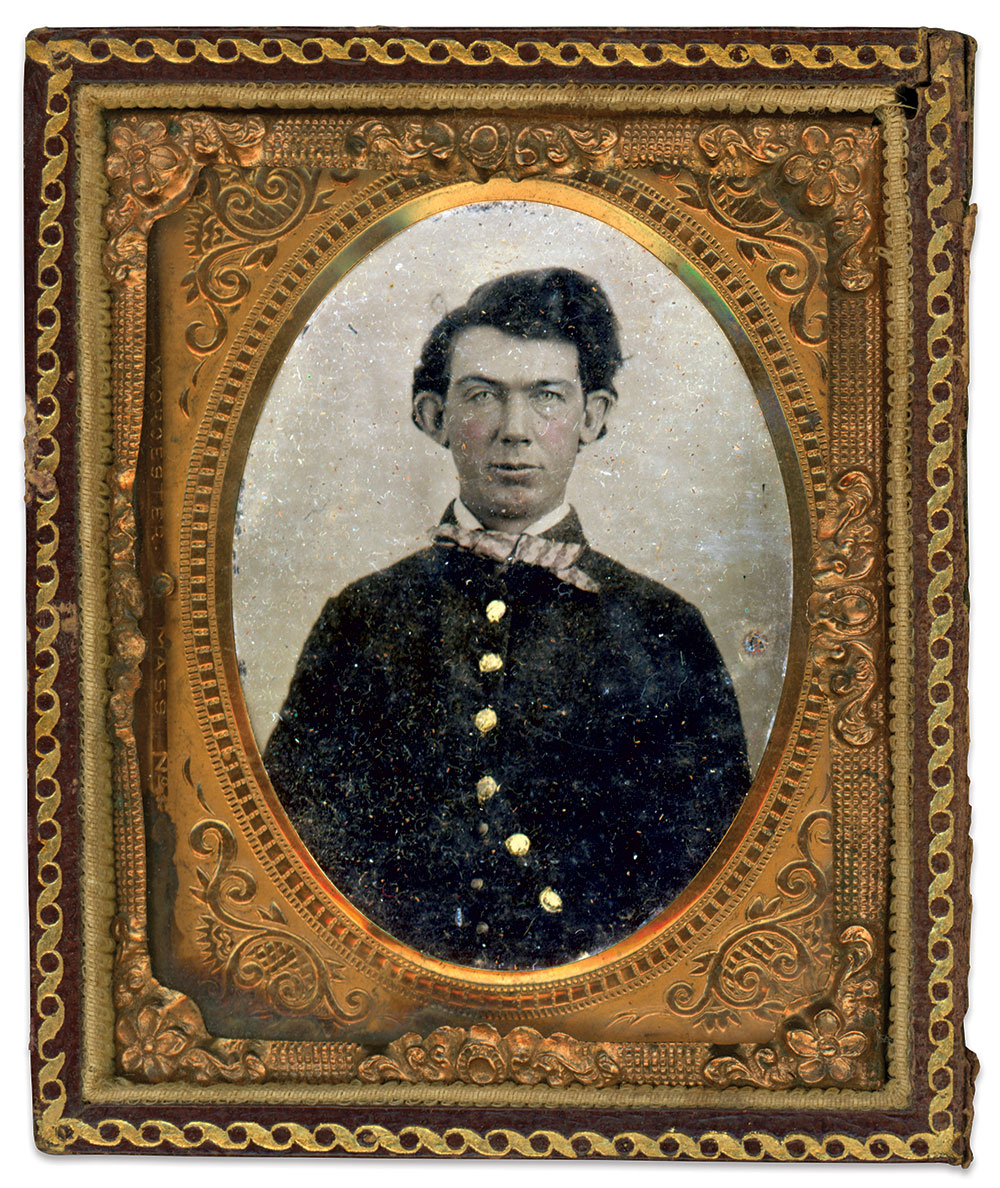

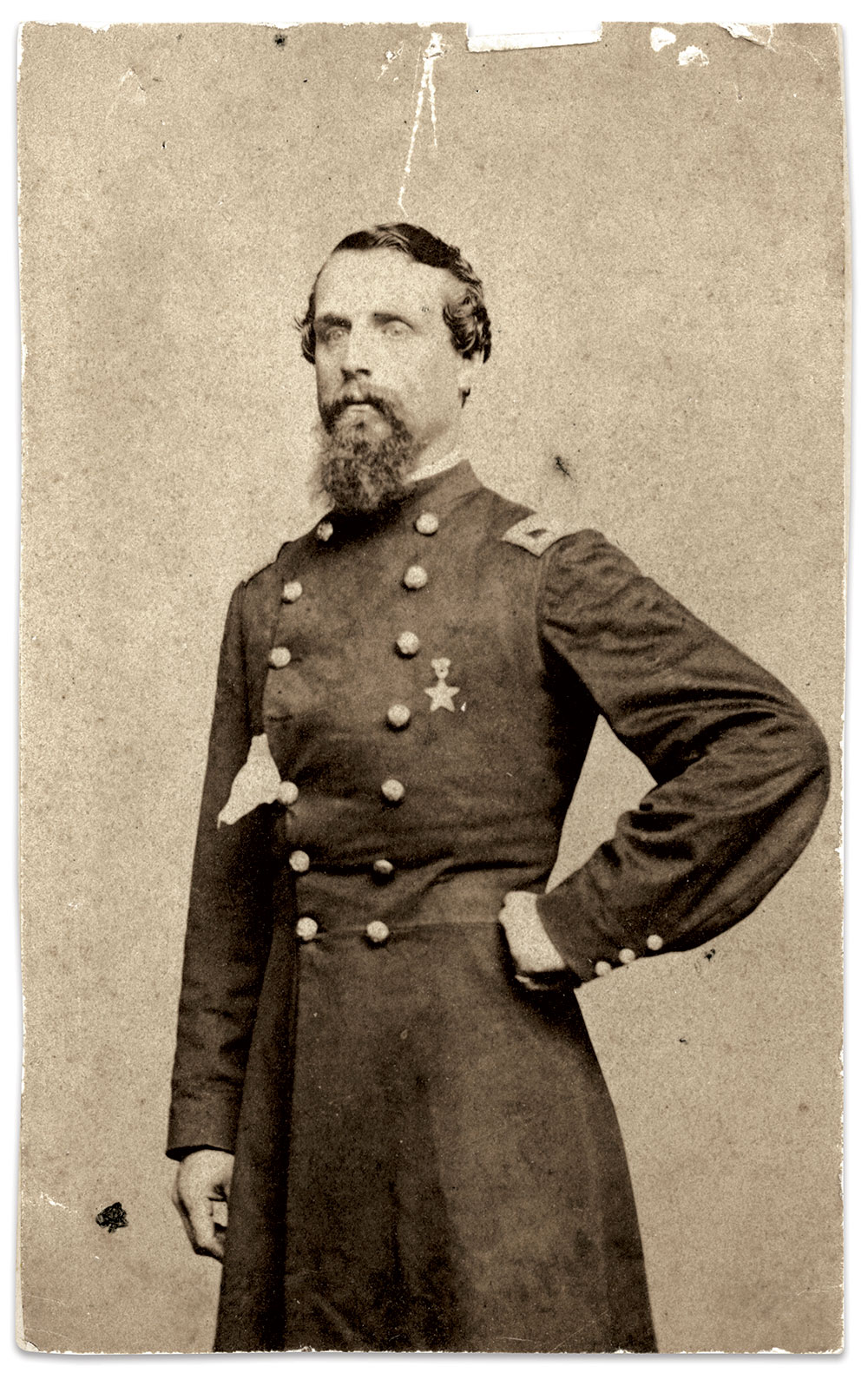

Sergeant to General

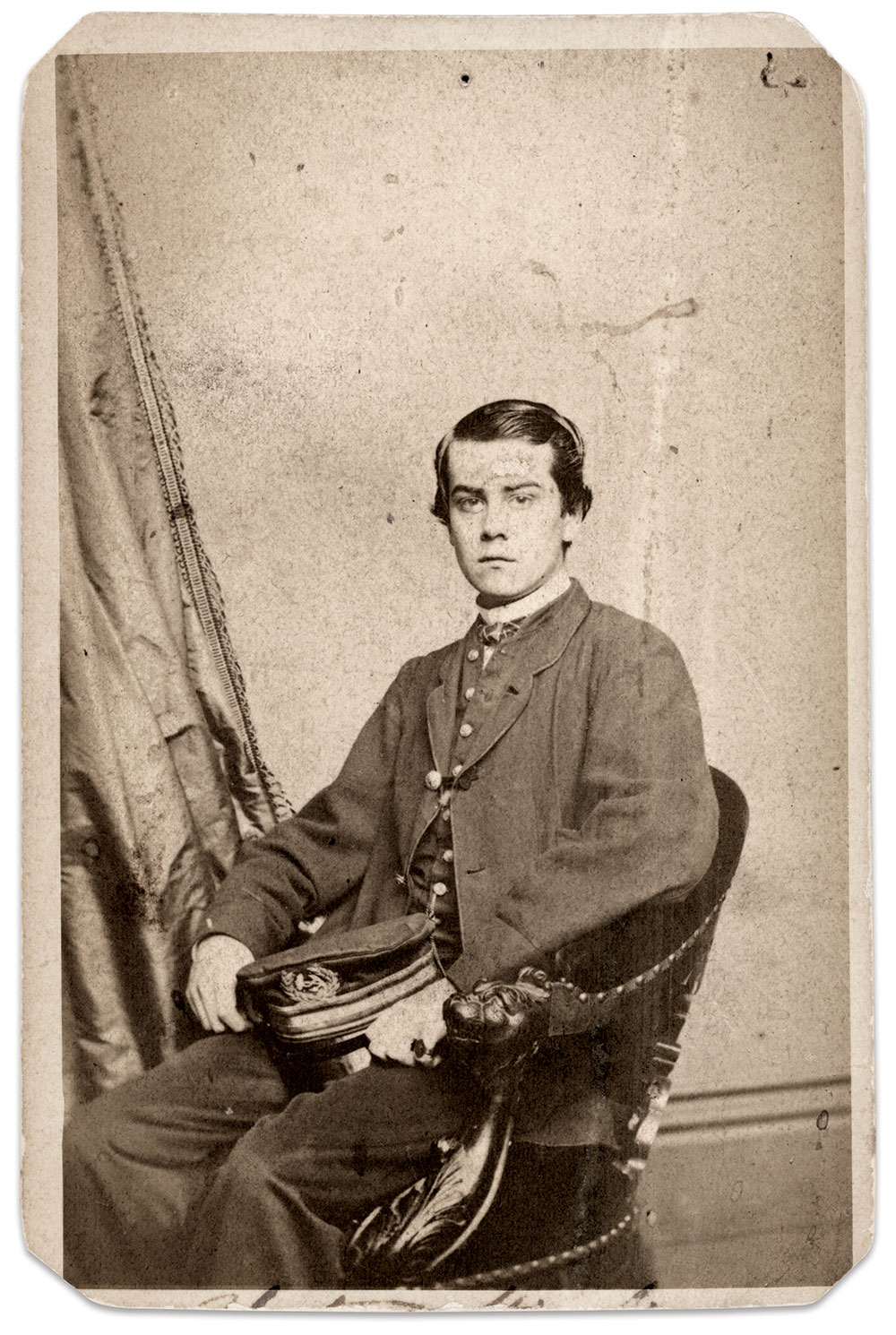

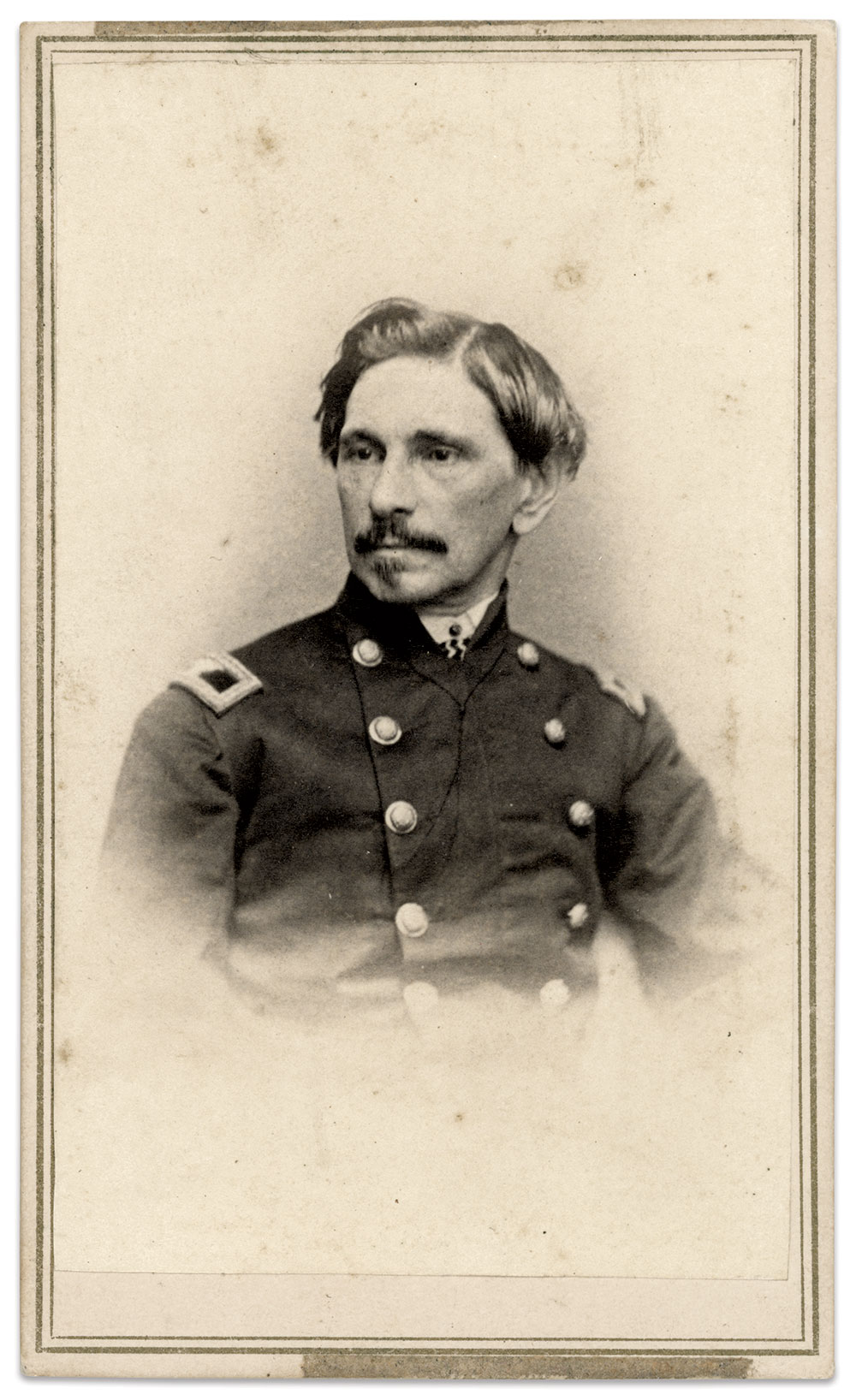

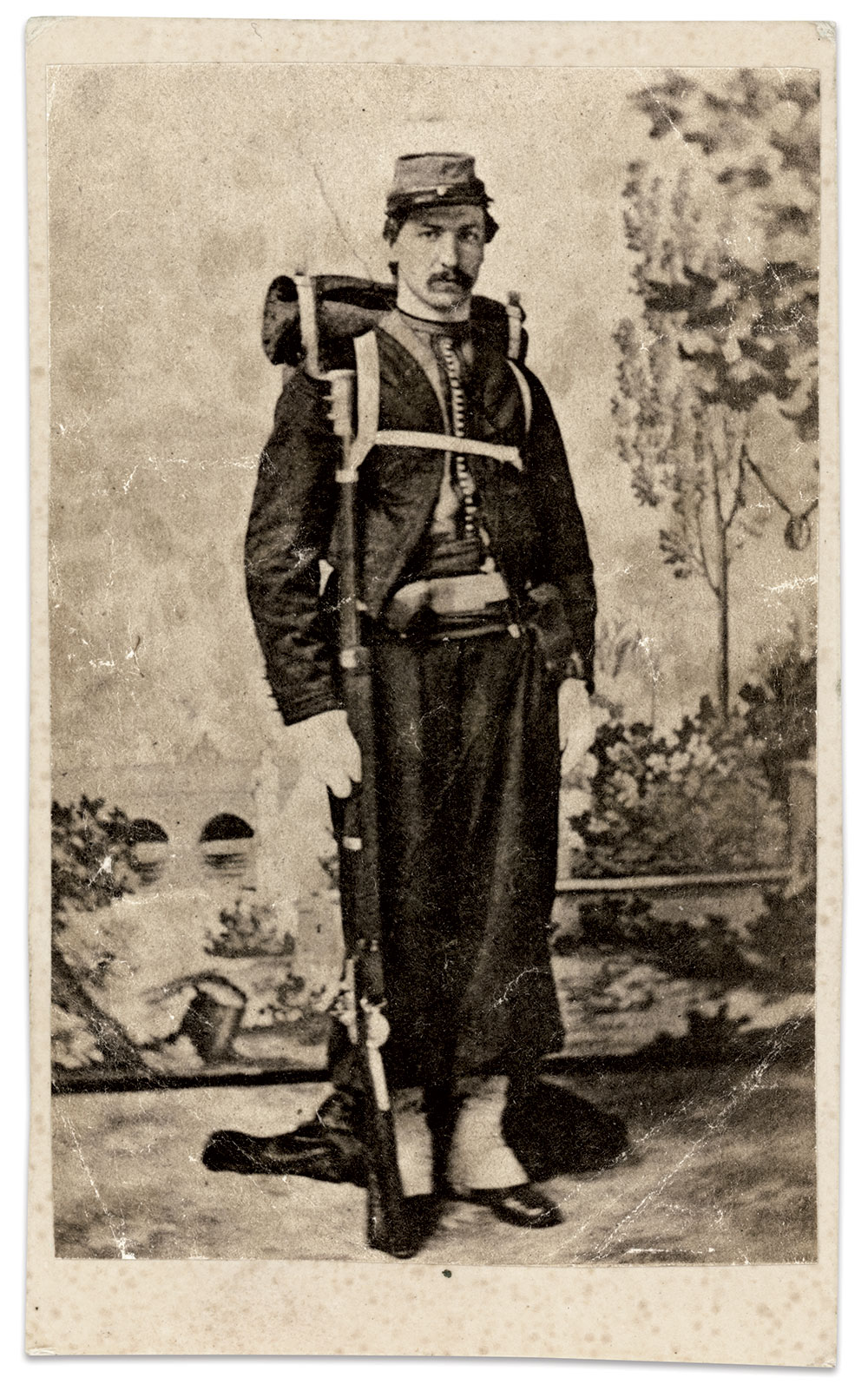

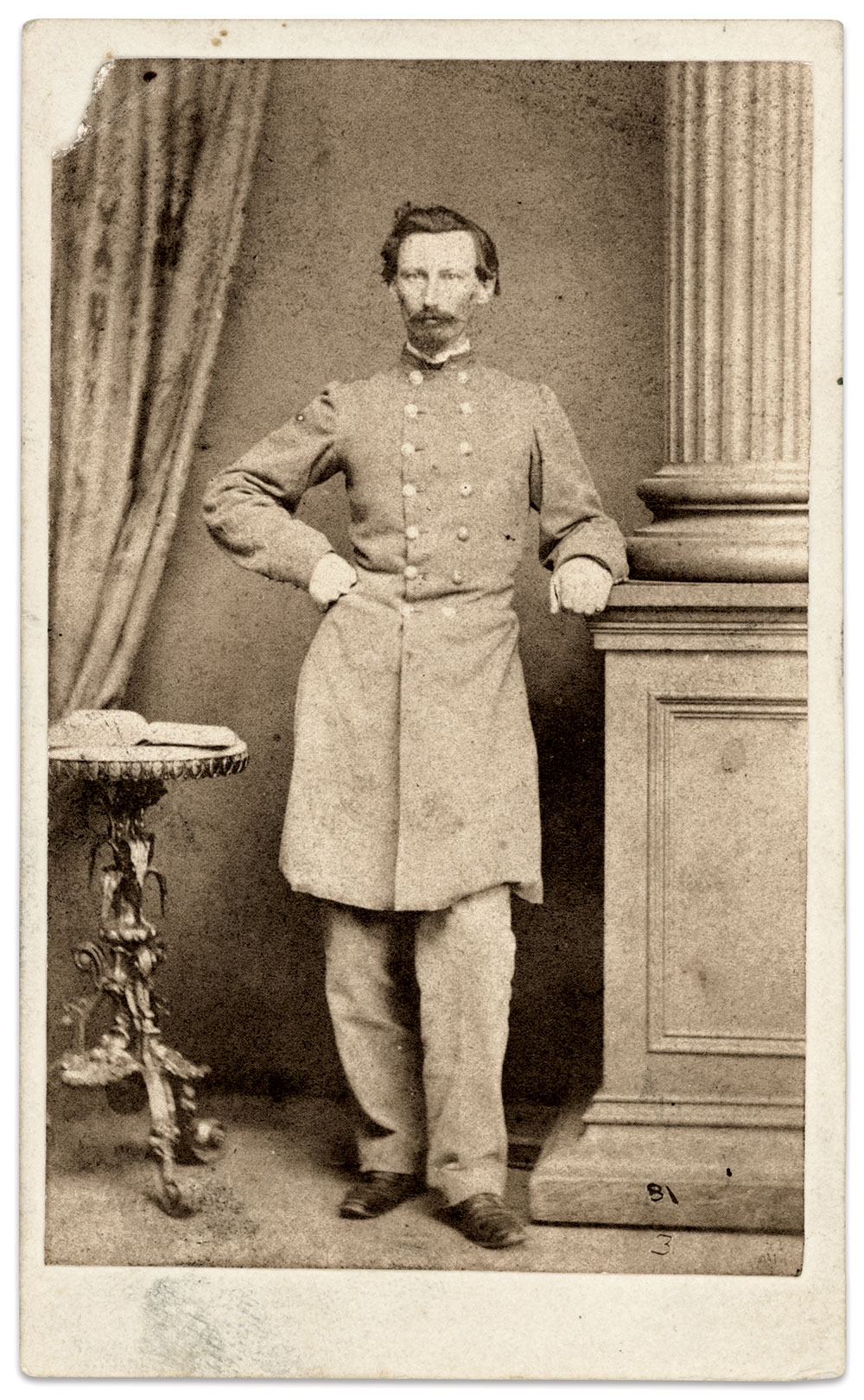

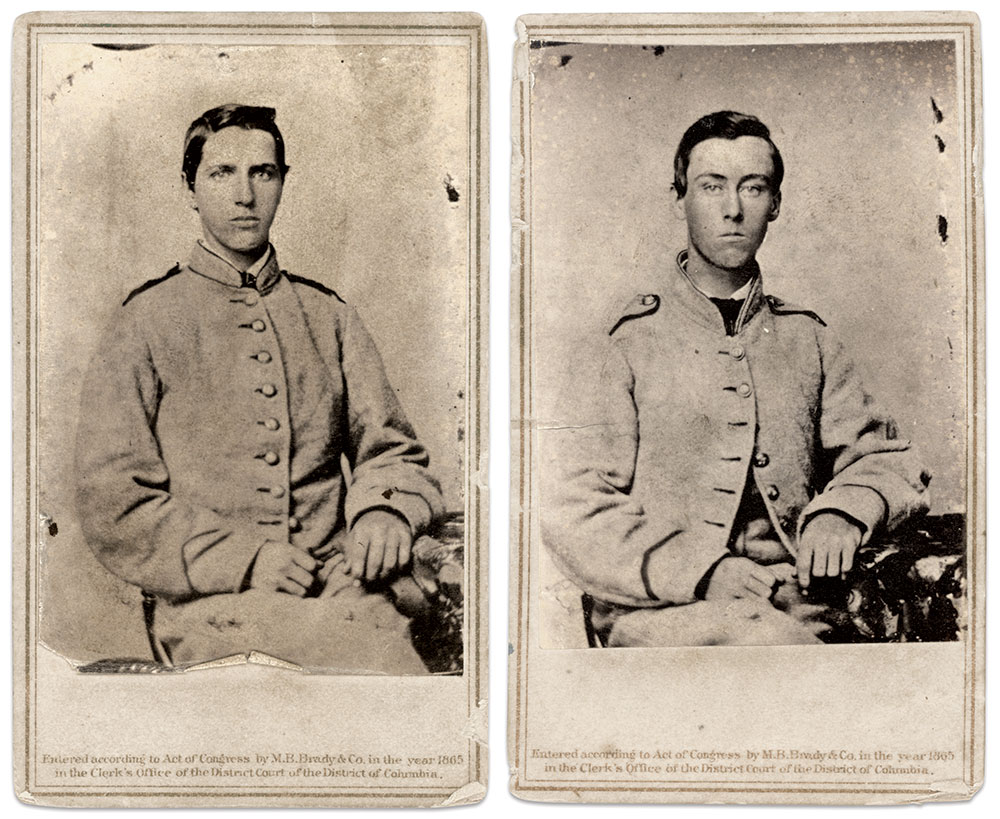

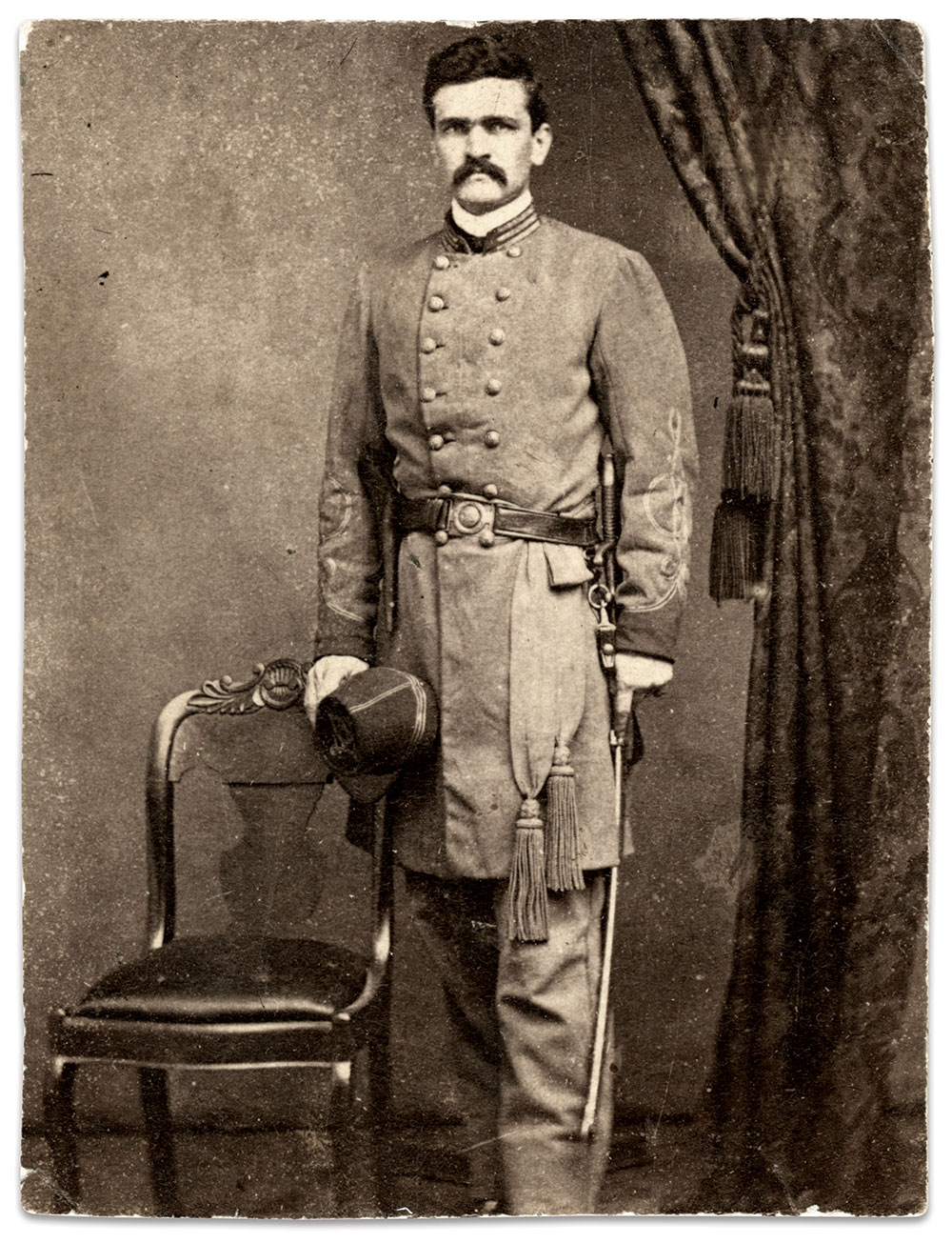

Baltimore pattern-maker David Leroy Stanton, 21, began his war service in May 1861 as first sergeant of Company A of the 1st Maryland Infantry. He’s pictured here soon after his enlistment. Four years later, he ended his service as a brevet brigadier general and brigade commander. Along the way, he fought in 17 engagements, many in Virginia, including the May 1862 Battle of Front Royal, where he fell into enemy hands, and two 1864 battles in which he suffered wounds: Spotsylvania Court House and Weldon Railroad. He earned his brigadier’s brevet for gallantry at the April 1865 Battle of Five Forks. After the war, he managed the office of a military pension attorney and became active in the Grand Army of the Republic. Baltimore’s Post 36 of the G.A.R. was named in his honor. Stanton died in 1919 at age 79.

1st Maryland Battles the 1st Maryland at Front Royal

Early in the morning of June 6, 1862, Col. John Reese Kenly arrived by train in his hometown of Baltimore. The enthusiastic crowd who met him at the station could not have been prepared for his appearance—a severe saber cut and bullet wound in back of his head, a smaller cut on his neck, and heavy bruises on his face and chest. The injuries had occurred in the recent Battle of Front Royal, Va., where Kenly and his 1st Maryland Infantry were garrisoned when a enemy force three times their number attacked. The honor of leading the advance fell to the Confederate 1st Maryland Infantry commanded by Col. Bradley Johnson. Kenly’s Marylanders put up a stiff resistance against their Confederate brothers before they attempted a retreat and were cut off by reinforcements ordered in by overall commander Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson. They captured Kenly and his surviving command.

According to a report in the Baltimore Sun, “After Col. Kenly with his command was removed to Winchester, the officers of the First Maryland regiment (infantry) on the Confederate side visited him, as did also many of the rank and file,” adding, “it is well to state that during all these visits or interviews the kindest feelings were manifested towards them, those on the Confederate side honoring and praising those on the Federal side for the bravery displayed on the battle-field, as it (in their own expressions) ‘did honor to old Maryland.’”

Paroled to Baltimore, Kenly recovered, was exchanged, received his brigadier’s star, and went on to command on the brigade level for much of the rest of the war.

Back in Baltimore, Kenly could not support himself in his chosen profession as a lawyer. Though poverty stared him in the face, he refused to apply for pensions for the Civil War or previous service in the Mexican War. After he died in 1891 at age 73, his old adversary, Col. Johnson of the Confederate 1st, paid tribute to the modest hero, Kenly: “He would not sell his blood for gold nor commute his patriotism for greenbacks.”

Kenly left behind his 1873 book, Memoirs of a Maryland Volunteer, War With Mexico. He dedicated it to Zachary Taylor, who Kenly considered the “true type of the American soldier.”

“I Have Never Retreated Without Orders, and I Cannot Do It Now”

In 1886 at Washington, D.C., a team of French artists led by Théophile Poilpot unveiled the 20,000-square-foot canvas painting of the Second Battle of Bull Run. The scenes depicted included a U.S. officer on a bay horse with his sword raised: Lt. Col. William Chapman, a brigade commander in Maj. Gen. George Sykes’ division of U.S. Regulars. During a rear guard action near the Henry House, the enemy poured heavy fire into the brigade. Subordinates implored Chapman to pull back. He told them, “We have been put here for something, I don’t know just what; but I have never retreated without orders, and I cannot do it now.”

A son of Maryland and 1831 West Point graduate, Chapman’s service followed America’s westward expansion. In the Mexican War, he distinguished himself in the victorious 1847 Battle of Molino del Ray, where, as a 27-year-old captain in the 5th U.S. Infantry, he led the regiment after his superior officers became casualties. Chapman compared the intensity of fire at Molino del Ray to Second Bull Run, which resulted in a colonel’s brevet for gallantry. It turned out to be his last combat. Ailing, he went on sick leave and retired from active service in 1863. He died in 1888.

Fighting Quartermaster

Colonel James Lowry Donaldson proved his fighting mettle twice during the war. In February 1862, while serving as staff quartermaster in the military District of Santa Fé, New Mexico Territory, he engaged in the Battle of Valverde. In December 1864, he organized a combat unit from his quartermaster department for the Battle of Nashville.

Donaldson, son of a prominent Baltimore family, had graduated from West Point in 1836, and followed the professional path of many young officers in Florida, Mexico, and western outposts, including New Mexico, where he was stationed when the Civil War began. He is best remembered for keeping supplies flowing in the Department of the Cumberland in 1863 and 1864. His commanding officer, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, praised him: “Joining me at Chattanooga, at the period when all looked gloomy and foreboding, you unraveled the intricate meshes then surrounding the Quartermaster’s Department within my command, and restored system and order where confusion had triumphantly held sway.”

Donaldson received brevets of major general in the regular and volunteer armies for his wartime service and remained in the army until 1874. He died in 1885.

He “Never Failed In the Hour of Peril”

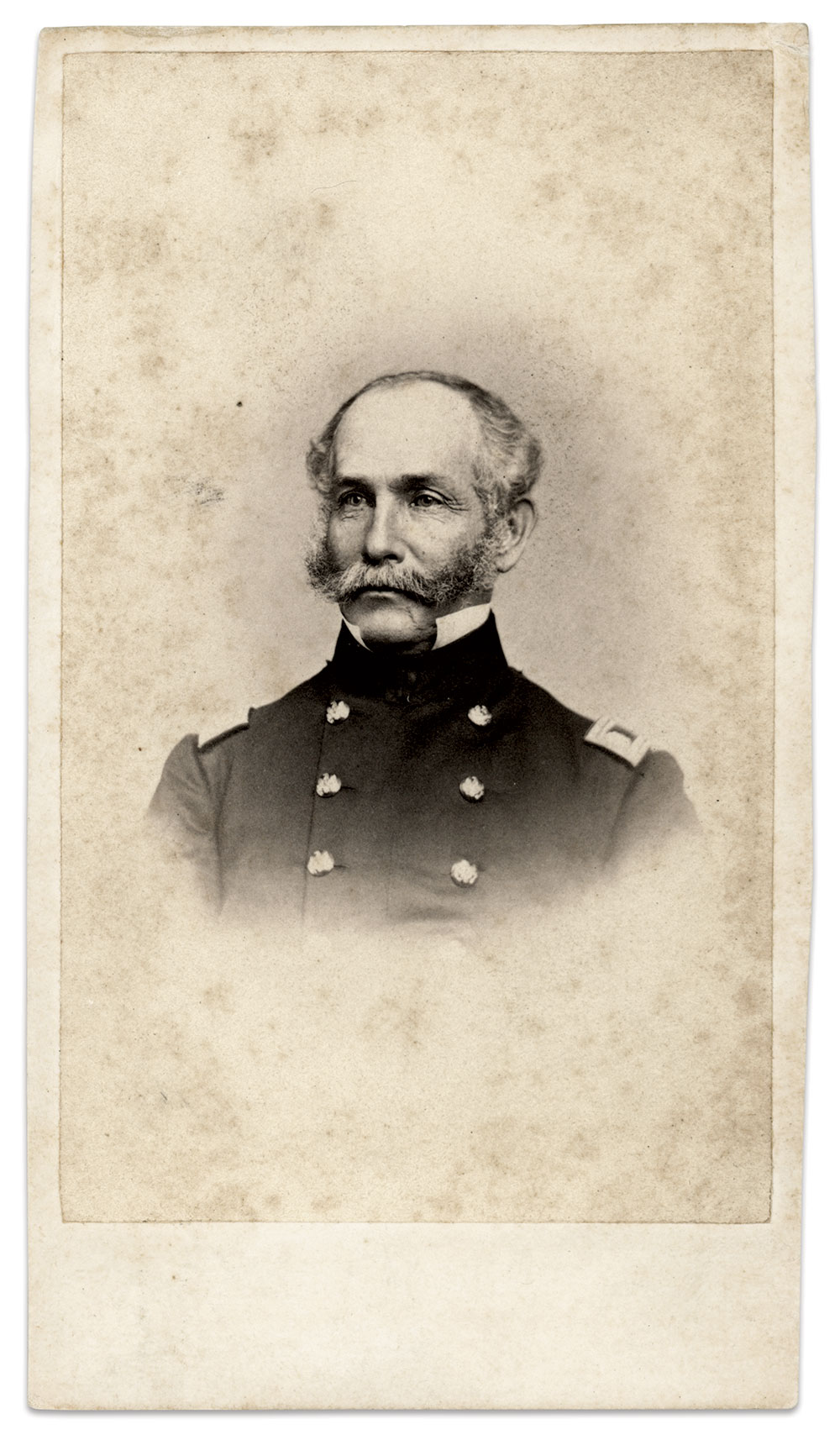

At Antietam, Baltimore-born Brig. Gen. William Henry French led his 2nd Corps division in the initial attack against Confederates in the Sunken Road. The fierce fighting that followed cost his division about 1,800 casualties. He wrote with pride and sorrow in his after-action report, “Receiving orders from the general in-chief to hold my position to the last extremity, it was done, but not without terrible loss.”

French had learned the arts of war in varied experiences since graduating from West Point in 1837, notably during the Mexican War, where he served as an aide to general and future U.S. President Franklin Pierce and received a pair of brevets for gallantry. When the Civil War began, his education and experience served him well in the Peninsula and Antietam campaigns, and the battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. He rose to major general and corps command along the way. French’s star faded during the 1863 Mine Run Campaign after Army of the Potomac commander George G. Meade faulted him for moving too slowly. Removed from command in early 1864, French continued on in an administrative capacity. French remained in the postwar army, retired in 1880, and died a year later at age 66.

At Antietam, a Homecoming of Sorts for a Color Bearer

At Antietam, the 148-strong 3rd Maryland Infantry fixed bayonets and charged past the Dunkard Church into a wooded area under orders to attack enemy infantry threatening an artillery position. Color sergeant David J. Weaver helped rally the Marylanders as they drove off the Confederates and held the position under heavy fire for two hours before ordered to retire.

For 28-year-old Weaver, the fighting was a homecoming of sorts. He had lived and worked as a coach maker about a dozen miles north in Williamsport, Md., prior to his enlistment in June 1861. Soon after the battle in the fields and woods of Sharpsburg, Weaver advanced to sergeant major. By the summer of 1863, he wrote with pride to an uncle, “I have been in 9 battles and still are safe. I enlisted a private and a perfect stranger to all in the regiment to which I belong and now I am a 1st lieutenant.” The battles included Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. Weaver went on to fight in others, among them Spotsylvania and The Crater. He managed to avoid wounds and mustered out as a captain in October 1864.

Weaver made his home in Cherrytree City, Pa., and died of cancer in 1892 at age 58. His wife, Catherine, and four children survived him. His Grand Army of the Republic comrades buried him with full honors.

Wounded Bugler from Ireland’s County Clare

The 1st Maryland Cavalry fought dismounted in operations against the Confederate defenses near Deep Bottom, Va., during the third week of August 1864. Several skirmishes and a successful charge that ended with the capture of rebel rifle pits cost the Marylanders nearly five score casualties, including Bugler Thomas J. Harr.

Born in County Clare, Ireland, Harr came to America with his family at age 11 in 1856. A laborer in Baltimore when the war began, he joined the 1st in early 1862 and participated in various actions in the Shenandoah Valley. He had the misfortune of being part of two companies on duty in the garrison of Harpers Ferry when Stonewall Jackson compelled its surrender just before the Battle of Antietam. Harr and his paroled comrades spent several months at Chicago’s Camp Douglas until being exchanged in early 1863. He spent much of the rest of the year on detached duties and sick in the hospital, missing the battles of Brandy Station and Gettysburg. He returned to the 1st for the Siege of Petersburg, including the Second Battle of Deep Bottom that resulted in his wound.

Harr soon recovered, returned to duty, and mustered out in 1865. He eventually settled in Fostoria, Ohio, where he died in 1907 at age 62. His wife and several children survived him.

Defending Free Press

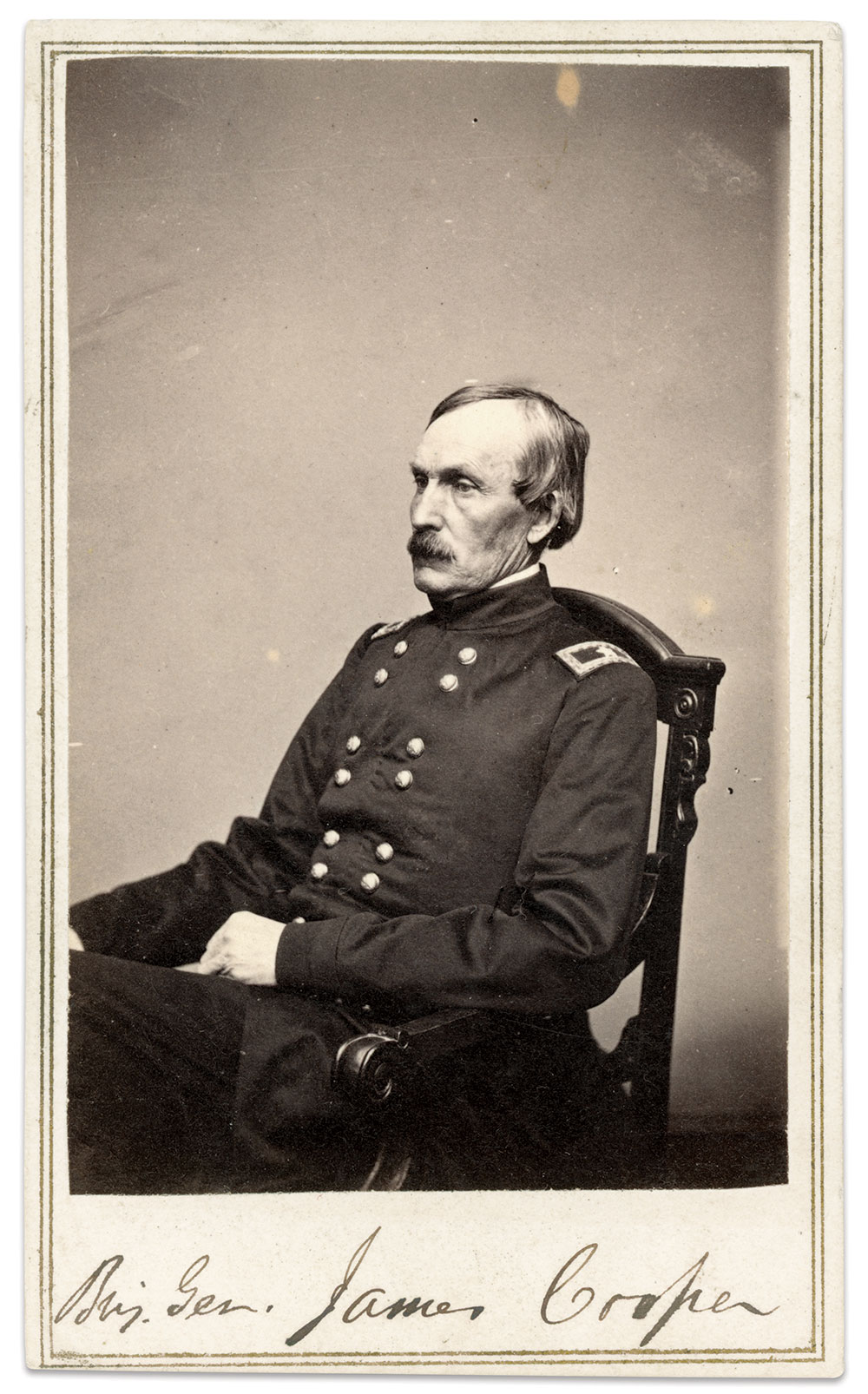

In Columbus, Ohio, on March 5, 1863, a mob of about 100 soldiers and citizens dressed as soldiers destroyed the offices of the Columbus Crisis, an anti-war newspaper supporting the faction of the Democratic Party known as Copperheads. The commander of nearby Camp Chase, Brig. Gen. James Cooper, stepped in to suppress the mob, restore order, and protect the rights of a free press—no small achievement in war.

Cooper, born in Maryland in 1810, graduated from college in Pennsylvania and settled into a law career in a crossroads town called Gettysburg in the 1830s. He rose to become a U.S. Senator aligned with fellow Senator Thaddeus Stevens. Cooper retired in 1855 and practiced law in his native Maryland. When war loomed, he came out of retirement to keep Maryland in the Union. When war came, President Abraham Lincoln authorized Cooper to recruit a army brigade. He did, and after campaigning in West Virginia, received orders to command Camp Chase, the military base and prisoner of war facility near Columbus.

Cooper proved an able administrator and defender of liberty and freedom. He died of pneumonia only three weeks after the incident at the Columbus Crisis office.

Five Months at Belle Isle; a Lifetime of Suffering In Mental Institutions

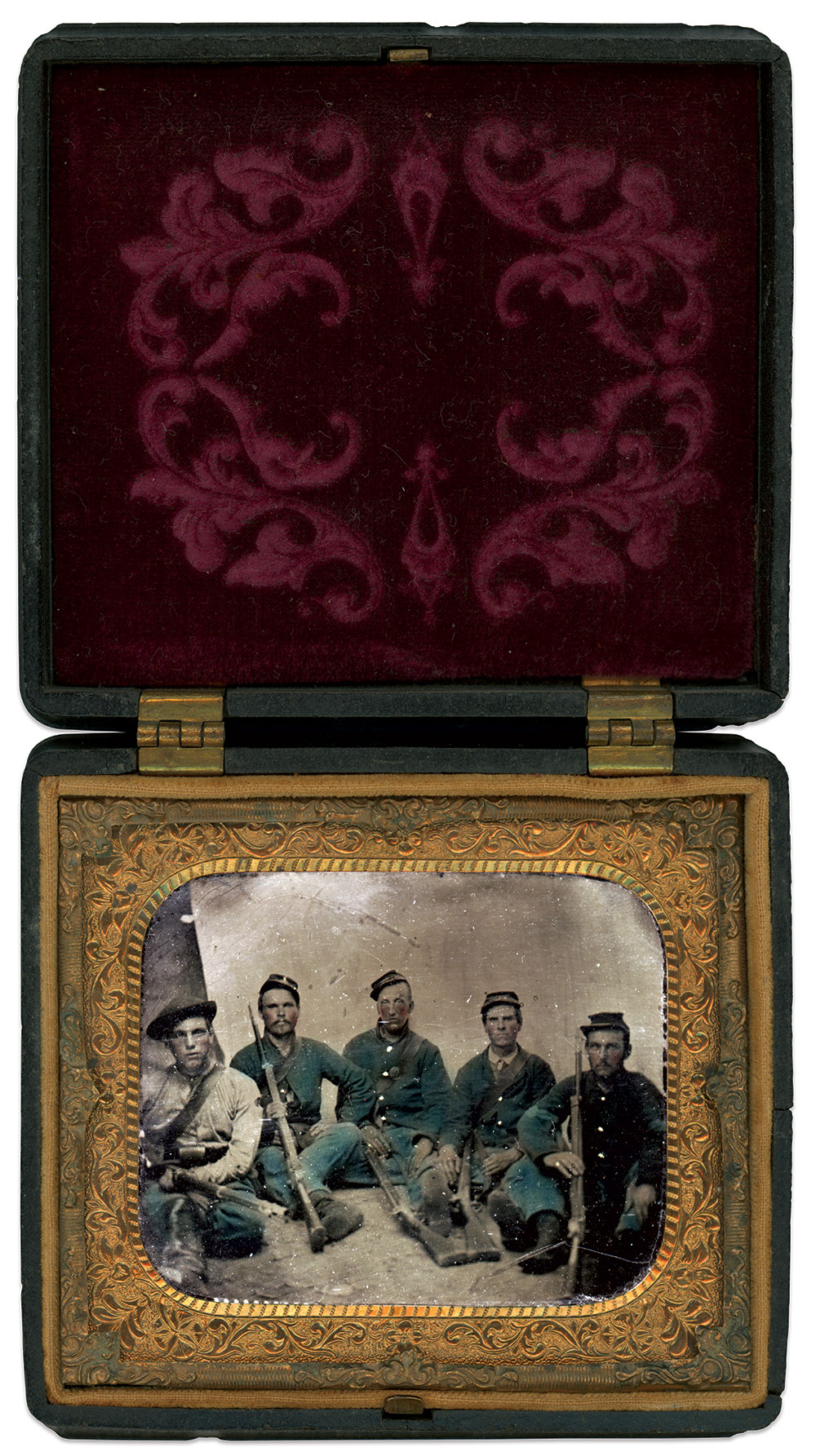

When William T. Carter enlisted in the 9th Maryland Infantry in June 1864, he may have expected an uneventful six-month enlistment, as evidenced by his casual pose with four pards. It turned out to be the opposite. On October 18, Confederates captured him and most of the men and officers in his regiment at Charles Town, W. Va.—casualties of a raid conducted by Confederate Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden. Carter spent the next five months at Belle Isle prison in Richmond, and after his release in March 1864 a lifetime in and out of mental institutions. He died in 1927 at about age 85.

“Hullo, Uncle Harry!”

In September 1863, Union forces advanced from the Rappahannock to the Rapidan rivers in Virginia. For one officer, a Marylander fresh out of West Point, the campaign proved his mettle as a soldier. Jacob Henry Counselman, a second lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Artillery, was praised in after-action reports for his leadership and the accuracy of guns in his Battery K. The campaign is also memorable for an incident recounted by Lt. Col. Theodore Lyman, an aide to Army of the Potomac commander George G. Meade. Lyman described a charge in the vicinity of Culpeper made by Brig. Gen. George A. Custer that resulted in the capture of three enemy cannon and a number of prisoners. Lyman added: “A queer thing happened in the taking of the three guns. An officer was made prisoner with them, and, as he was marched to the rear, Lieutenant Counselman of our side cried out, ‘Hullo, Uncle Harry!’ ‘Hullo!’ replied the captain’s uncle. ‘Is that you? How are you?’ And there these two had been unwittingly shelling each other all the morning!”

The meeting of uncle and nephew illustrates Maryland’s divided loyalties. Counselman did not resign from West Point when the Civil War began and graduated in June 1863. Assigned to the 1st Artillery, he led his battery at Brandy Station, earning a brevet, and other operations in Virginia until June 1864, when he became lieutenant colonel of the 1st Maryland Cavalry and served with distinction until the war’s end.

Counselman returned to the 1st Artillery after the war, but ill health cut his life short in 1875 at about age 34. His remains rest in Arlington National Cemetery.

Punished by Standing on a Barrel

In April 1864, a court martial found Pvt. James D. Ricketts of the 4th Maryland Infantry guilty of two charges after a guard duty incident. The first charge, being absent without leave, cost him five dollars and ten days policing grounds under guard. The second, disobedience of orders, cost him another five greenbacks plus the indignity of standing on a barrel for six consecutive hours, six days in a row.

This was not the first time Ricketts landed on the wrong side of military law. The Baltimore-born laborer was absent without permission on several occasions following his enlistment as a drummer in mid-1862. Despite his problematic record, he remained in the ranks until the regiment mustered out of service in 1865. He died in 1890.

Captured by Mosby, Sent to Andersonville

Colonel John Singleton Mosby and his Rangers disrupted federal communications along the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in West Virginia as part of an effort to support Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s 1864 Raid on Washington, D.C. On June 29, they posted a howitzer overlooking Duffields Depot and compelled the surrender of its Union garrison. The Rangers burned the depot and left with about 50 prisoners, including Pvt. John J. White of Maryland’s 1st Potomac Home Brigade.

White went on to be confined at Andersonville until early 1865, when he was paroled and sent north to Benton Barracks in St. Louis. In May 1865, White returned to his home in Frederick, where he died in 1923 at age 79.

Maryland Military Connection

Some of Maryland’s soldiers had minor connections to the Old Line State. They include William H. Revere, Jr., who organized the 10th Maryland Infantry in 1863 and led it as colonel for a six-month enlistment. Born in Illinois, Revere belonged to Elmer E. Ellsworth’s famed U.S. Zouave Cadets. Revere followed Ellsworth into the 11th New York Infantry when the war began. After an innkeeper gunned down Ellsworth when he removed a Confederate flag from an Alexandria, Va., hotel in May 1861, Revere received a captain’s commission in the 44th New York Infantry, popularly known as “Ellsworth’s Avengers.” He served through the 1862 Peninsula Campaign and the Second Battle of Bull Run before leaving the 44th to organize the 10th Maryland. Following its disbandment he became colonel of the 107th U.S. Colored Infantry and barely survived the war, dying of fever in September 1865 while on duty in Morehead City, N.C. He was about 33 years old. His superior officer, Col. Delavan Bates, praised Revere as “a very energetic, hardworking, and efficient officer.”

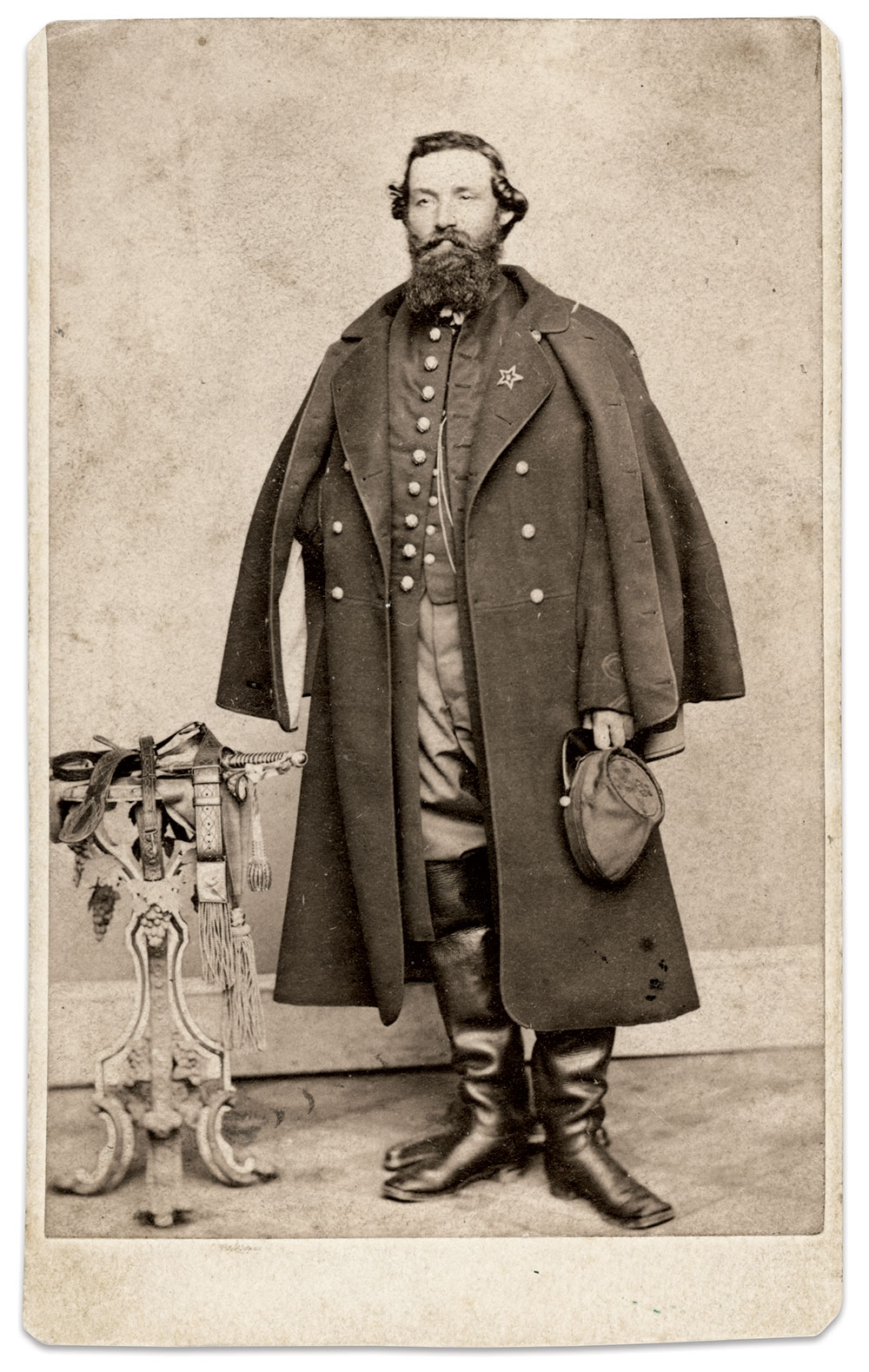

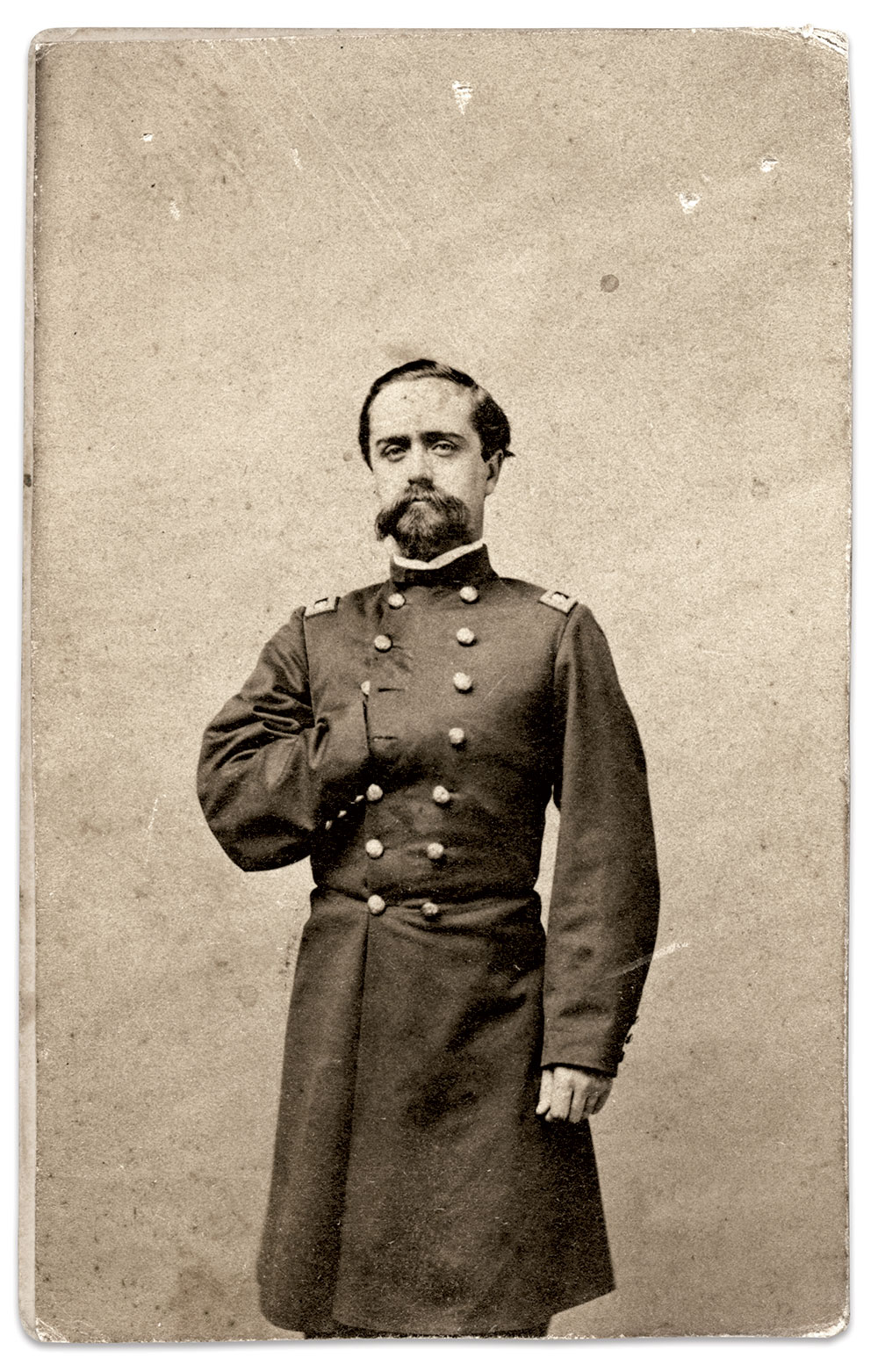

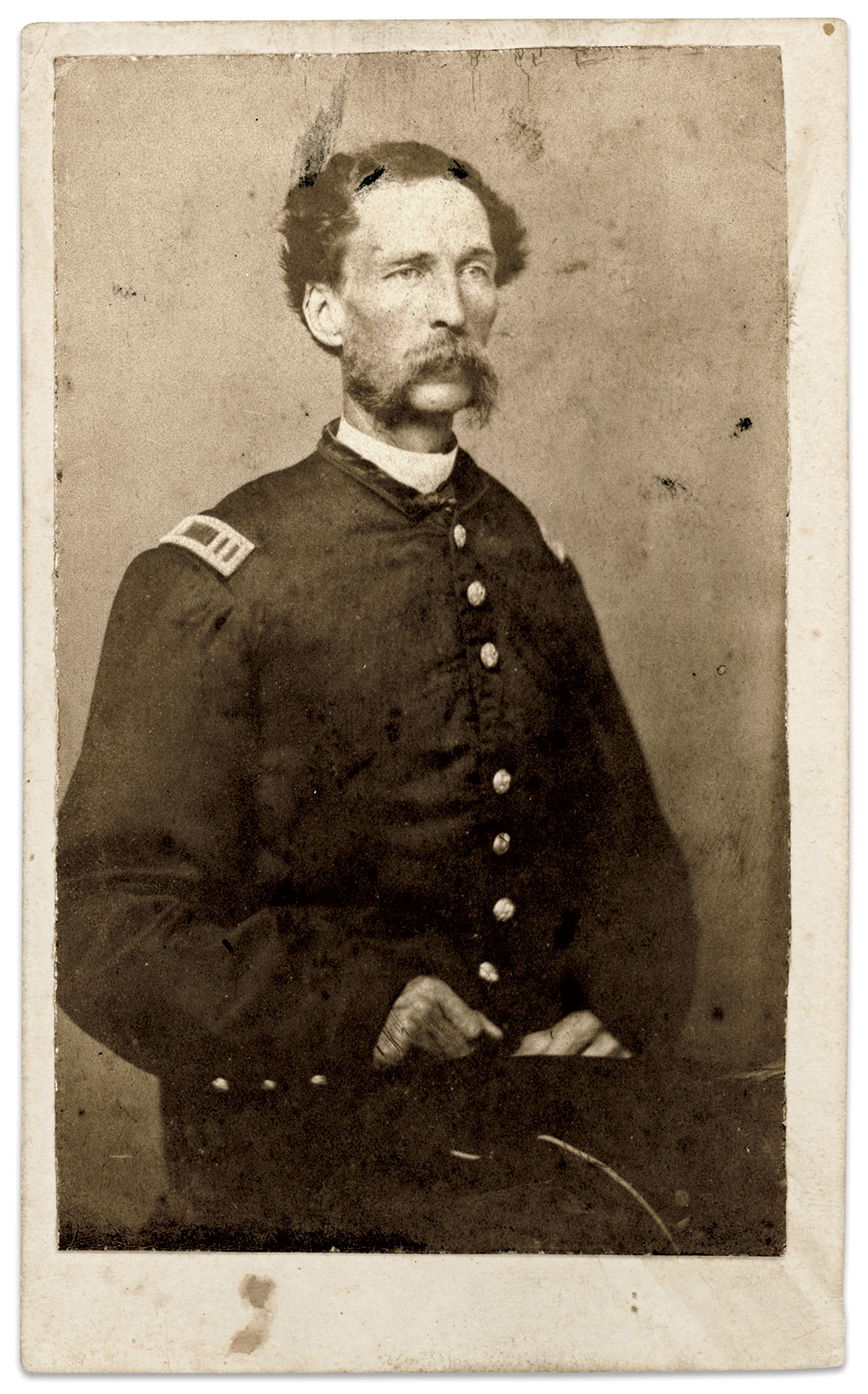

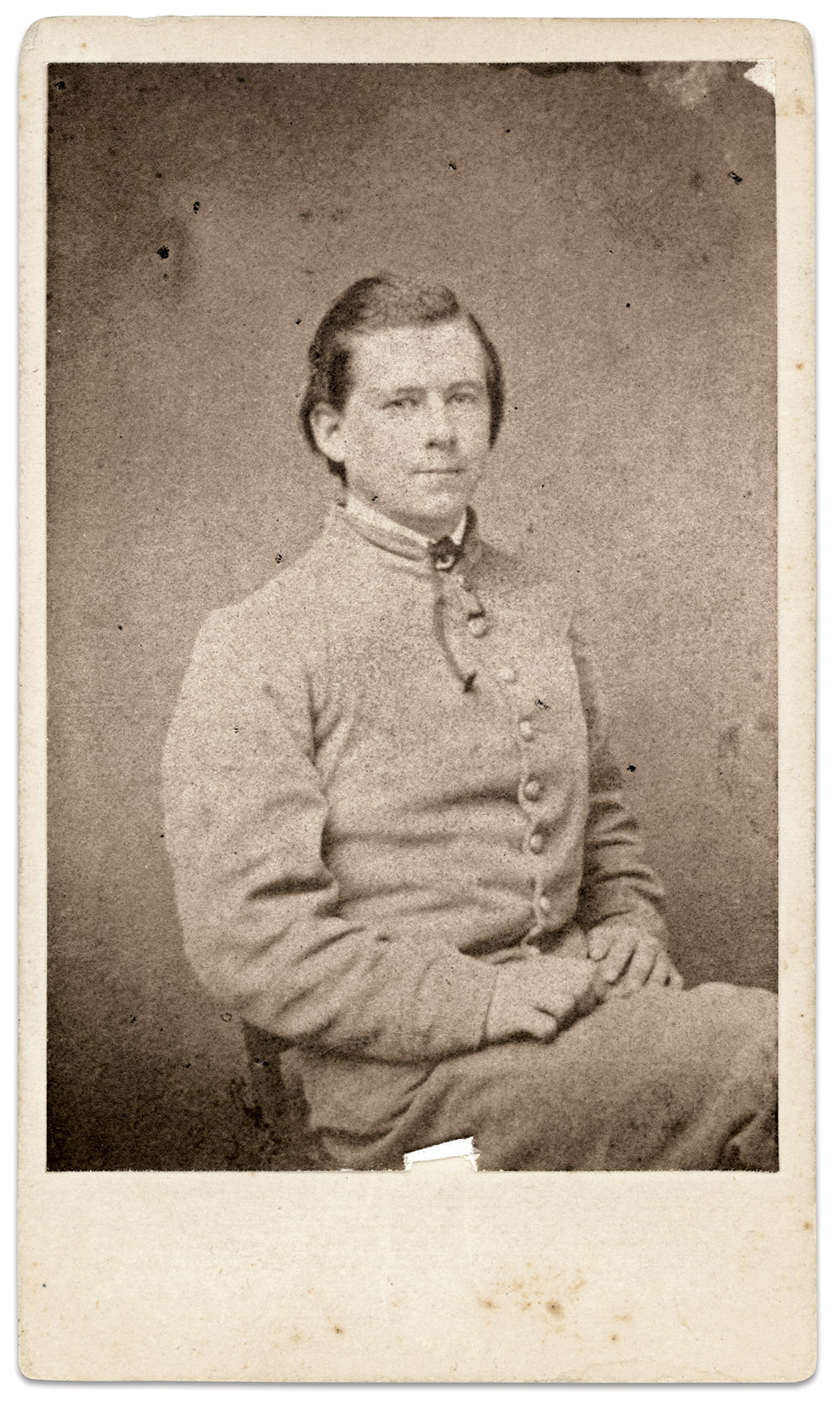

A 100-Day Man at Monocacy

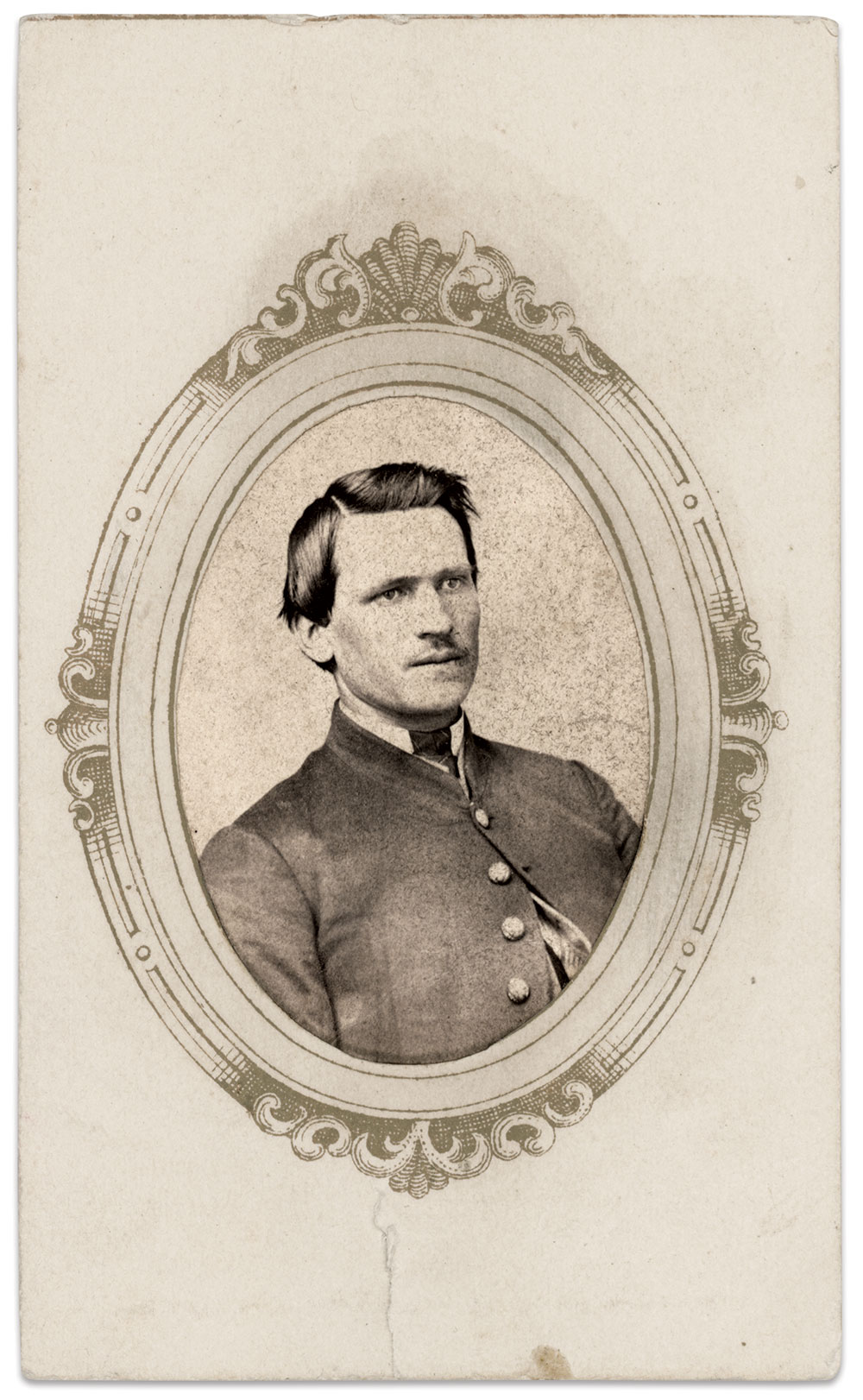

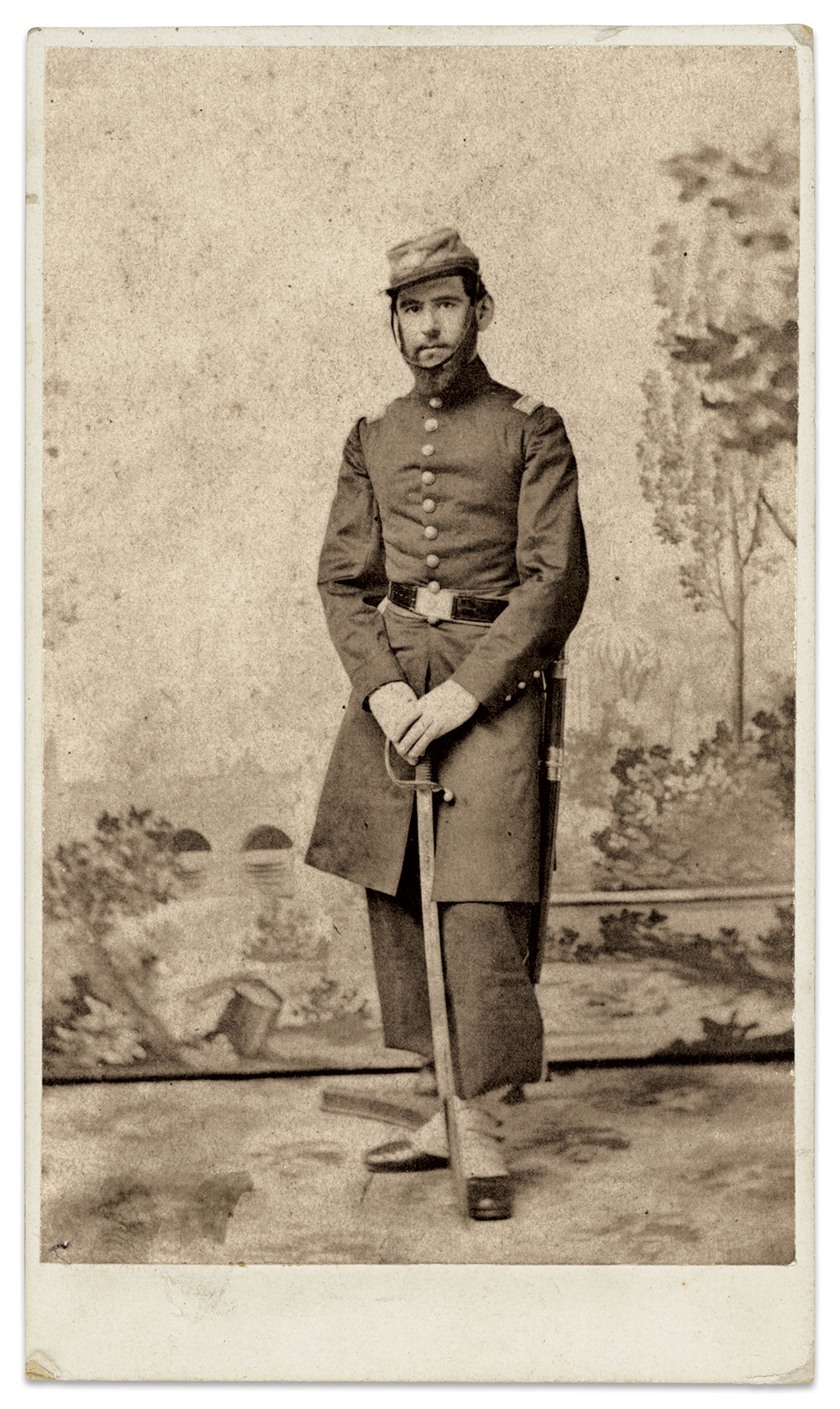

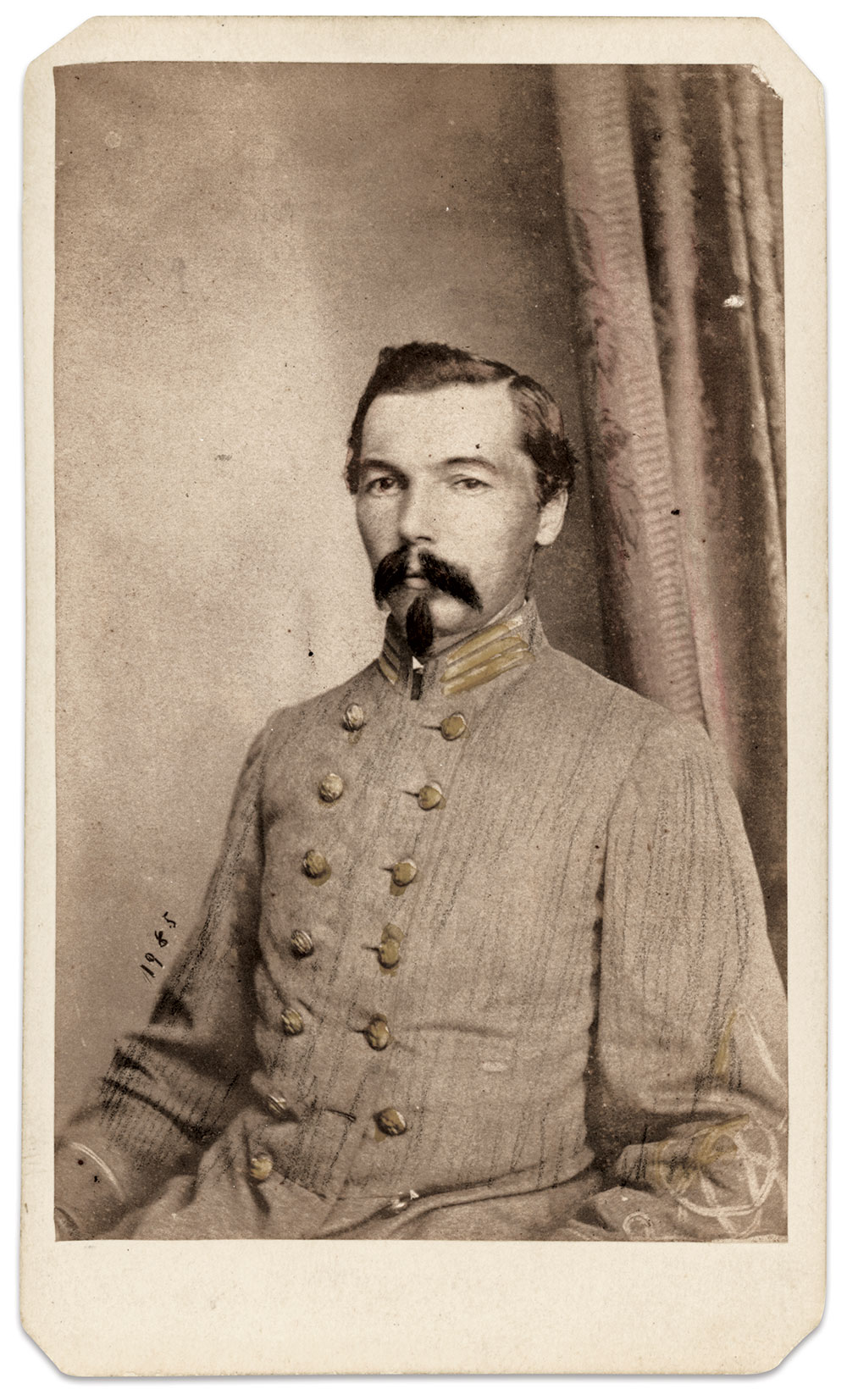

Captain Archibald D. Ferguson, a Baltimore grocer, and his comrades mustered into the 11th Maryland Infantry for a 100-day enlistment in mid-June 1864 with an understanding that they would take charge of part of the Defenses of Baltimore and free up seasoned troops for combat. Ferguson noted on the back of this portrait, “When I entered the service.”

Three weeks later, the green Marylanders found themselves in the Battle of the Monocacy against battle-hardened Confederate veterans in Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s Corps. The 11th, part of the 1st Separate Brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Erastus B. Tyler, contributed to the Union victory. According to an Ohio officer in another brigade, the colors of the 11th were left on the field and recovered by U.S. forces.

The Marylanders completed their brief term, and many reenlisted for a full year in the new 11th. Ferguson joined them and spent his time in Baltimore as provost marshal on Brig. Gen. Tyler’s staff. The last time Ferguson’s name appears in records is 1869.

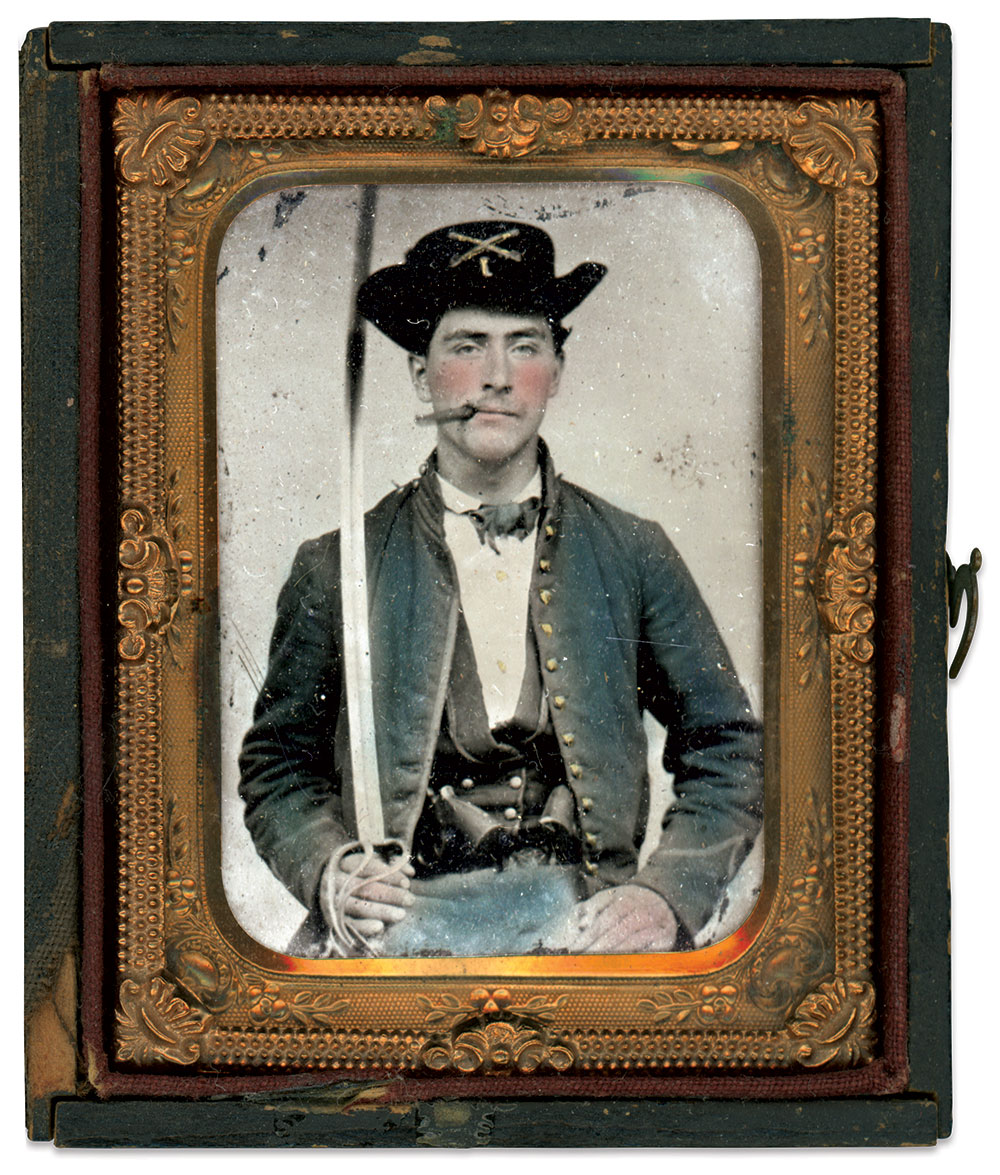

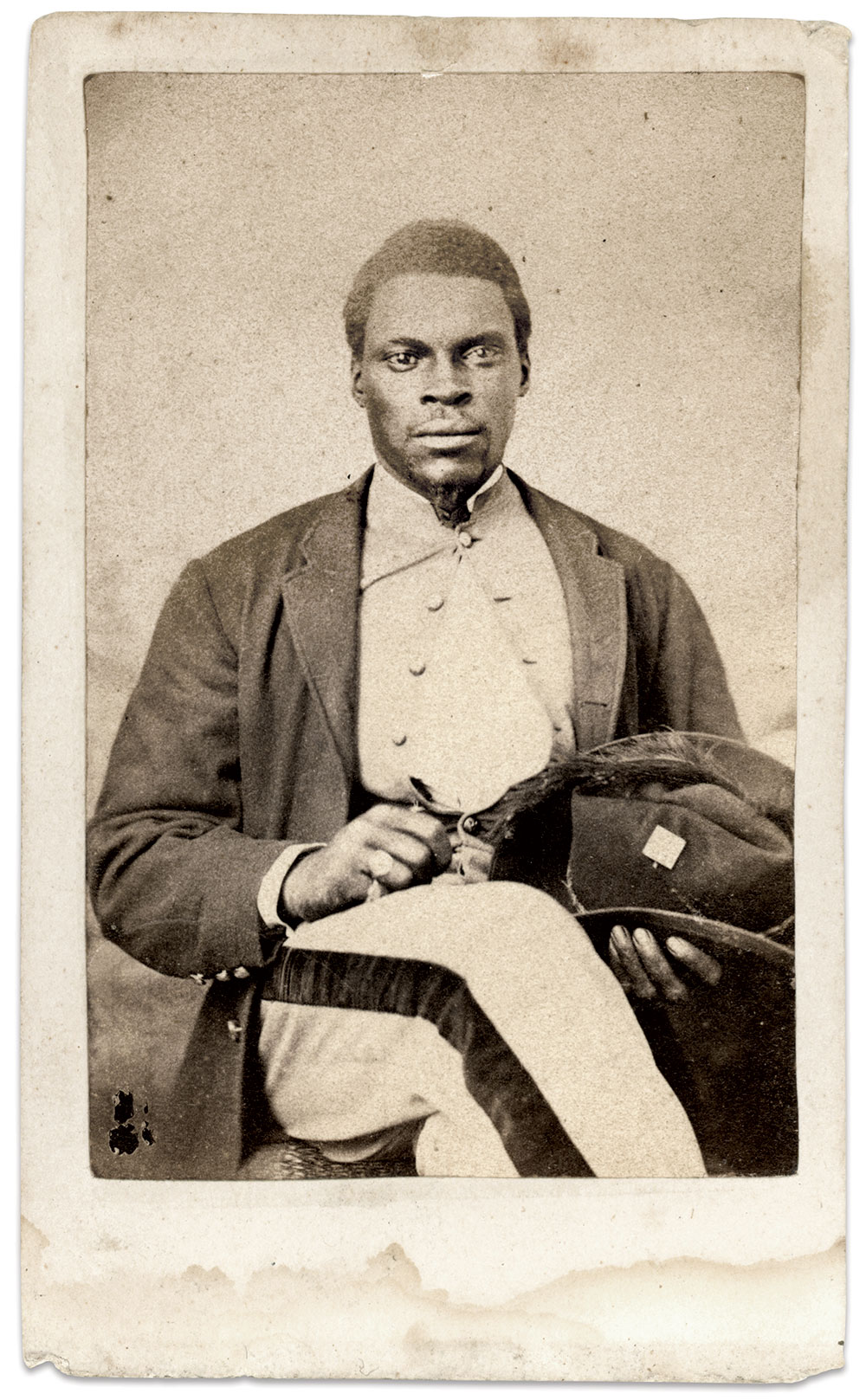

At The Crater and in Texas

Enslaved in Southern Maryland, Peter Butler was not freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. His enslaver, former judge and state legislator Peter Crain, consented for Butler to join the U.S. Army in late 1863. He enlisted as a private in the 19th U.S. Colored Infantry, received basic training in Baltimore, and reported for duty with his regiment to Virginia with the Army of the Potomac’s 25th Corps. He wears the diamond-shaped badge of the Corps on his plumed hat. The 19th participated in the 1864 Siege of Petersburg and fought at the battles of the Crater and Bermuda Hundred. Along the way, Butler advanced to corporal of Company B.

After hostilities ended, the War Department dispatched 50,000 men, including the 19th, to Texas as a show of force against French troops occupying Mexico. Butler mustered out at Brownsville, Texas, in January 1867—the last time his name appears on a government record.

U.S. Colored Troops and Ex-Confederates Join Forces in Texas to Invade Mexico

During the night of Jan. 4-5, 1866, along the Texas-Mexico border, an irregular force of about 125 volunteers composed of the 118th U.S. Colored Infantry and ex-Confederate soldiers crossed the Rio Grande on an English schooner and landed in Mexico. By morning, they captured forts near the town of Bagdad, its garrison of about 200 Austrian soldiers, and four cannon. Three French warships sent landing parties to recapture the town and were repulsed by the Americans. The ranking U.S. officer turned Bagdad over to Mexican Gen. Mariano Escobedo on January 6, and returned with his men to Texas.

This is one version of the account of the U.S. incursion into French-occupied Mexico, as told by strike force commander Lt. Col. Isaac D. Davis of the 118th. The 25-year-old native of Cecil County began his military service in 1861 as a corporal in the 5th Maryland Infantry, rose to commissary sergeant, and left the regiment in 1864 to accept a captain’s commission in the 118th. In July 1865, he advanced to lieutenant colonel.

Less than a month after Davis’ troops captured Bagdad, Napoleon III announced a staged withdrawal of French troops from Mexico. Davis told his story in 1896, claiming he acted without orders but that his superior officer, 25th Corps commander Maj. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel, was aware of the plan. Davis noted that the expense and tedium of maintaining a strong military presence while diplomatic negotiations dragged on motivated him to act: “All were heartily tired of the inactivity and anxious to strike a blow for the liberation of Mexico and the vindication of the Monroe Doctrine.”

Davis died in 1920 at age 78.

25,000 Fought for the Confederacy.

President Jefferson Davis held high hopes that Maryland would secede from the Union and join the Confederate States. During the earliest part of the conflict it seemed possible. Davis observed in his memoirs,“The story of Maryland was sad to the last degree, only relieved by the valor of the gallant men who left their homes to fight the battle of State-rights, when Maryland no longer furnished them a field on which they could maintain the rights their fathers bequeathed to them. Though Maryland did not become one of the Confederate States, she was endeared to the people thereof by many most endearing ties.”

Pro-Secession Mob in Baltimore, Pro-Union Mob in Williamsport

Dewitt Clinton Rench of Williamsport spoke often and publicly about his Southern sympathies. The son of a wealthy farmer who enslaved seven persons in Washington County, Rench graduated from Franklin and Marshall College in Pennsylvania and studied law with an uncle in Baltimore, where he joined the Maryland Guard Battalion.

Rench participated in the pro-secession riots in Baltimore on April 19, 1861, according to a historian of the 6th Massachusetts Infantry. The 6th suffered many casualties after protestors attacked, including 17-year-old Luther C. Ladd. “The murderer of Ladd was probably a drunken, dissolute wretch named Wrench. He afterwards often boasted of the deed, and rejoiced in having killed that ‘boy soldier who shouted for the Stars and Stripes when he fell.’”

Rench met his end two months later while in Williamsport on business. A group of pro-Union men accosted Rench and told him to leave. He brushed them off and stepped into a store to smoke a cigar. Meanwhile, a large and angry mob gathered. When Rench walked outside and mounted his horse, a man grabbed the bridle. Hot words and gunshots were exchanged and Rench fell dead.

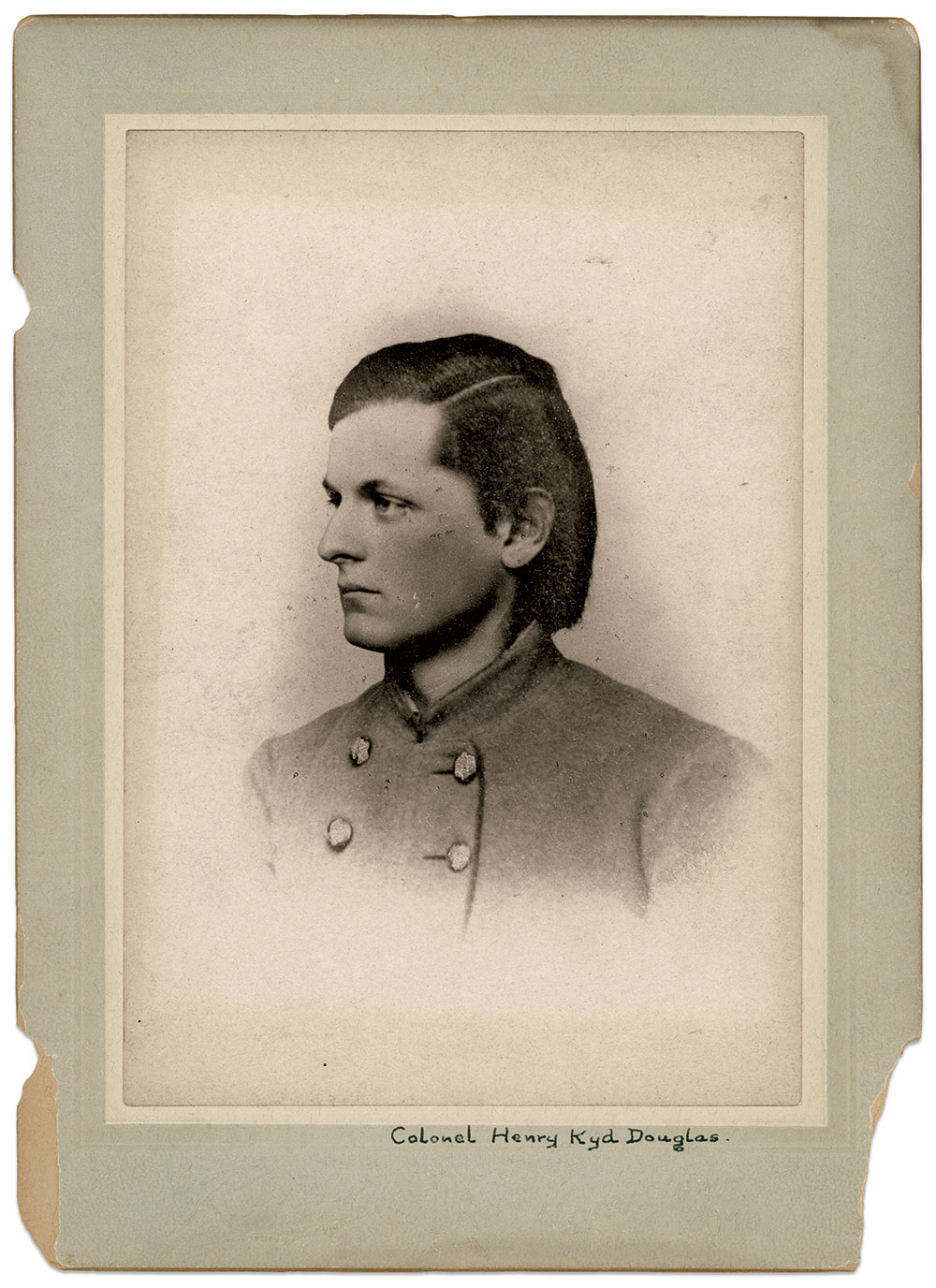

Word of his death made it to a Confederate army camp overlooking Williamsport. One of the officers, Lt. Henry Kyd Douglas, had been Rench’s close friend and college roommate. Douglas expected Rench to join him in the army. His anticipation turned to grief.

Cheers for Baltimore and Richmond

On June 21, 1861, two companies of the 21st Virginia Infantry met for the first time at Camp Lee, near Richmond. Company B, composed of Baltimore’s cultural and financial elite, welcomed Company F, an old militia unit representing Richmond’s high society. The Baltimoreans gave the Richmonders three hearty cheers.

One of the Baltimore officers, 1st Lt. Richard Curzon Hoffman, had been born in Baltimore and worked there as a stockbroker. He had joined the Maryland Guard Battalion, a militia group formed in Baltimore in 1859. When the war came, he and many of his comrades left for Virginia, bringing their natty Zouave-inspired uniforms with them.

After the expiration of its one-year enlistment, Hoffman and other Marylanders joined the 30th Battalion Virginia Sharpshooters. Hoffman spent little time with the unit as he served on various detached duties. He remained in the army until the end of the war. Back in Baltimore, Hoffman became involved in the coal and railroad businesses. He died in 1926 at age 86, leaving behind a wife and children.

Killed at Iuka: “We Will Miss Him So Much”

A Maryland-born career soldier honored for courage in the Mexican War, Lewis Henry Little resigned his commission in 1861 and joined the Confederacy. At the March 1862 Battle of Pea Ridge, Ark., he proved an aggressive leader. Six months later at the Battle of Iuka, Little commanded the left wing of Maj. Gen. Sterling Price’s army. As Little conferred with Price, a minié bullet struck him just above his left eye and came to rest at the back of his head. He died instantly.

An artilleryman confided in his diary, “We will miss him so much, for he took such good care of his men. His body was quietly laid to rest that night, in a hastily prepared grave in Iuka.” Little’s remains were later exhumed and reinterred in Green Mount Cemetery in his hometown of Baltimore.

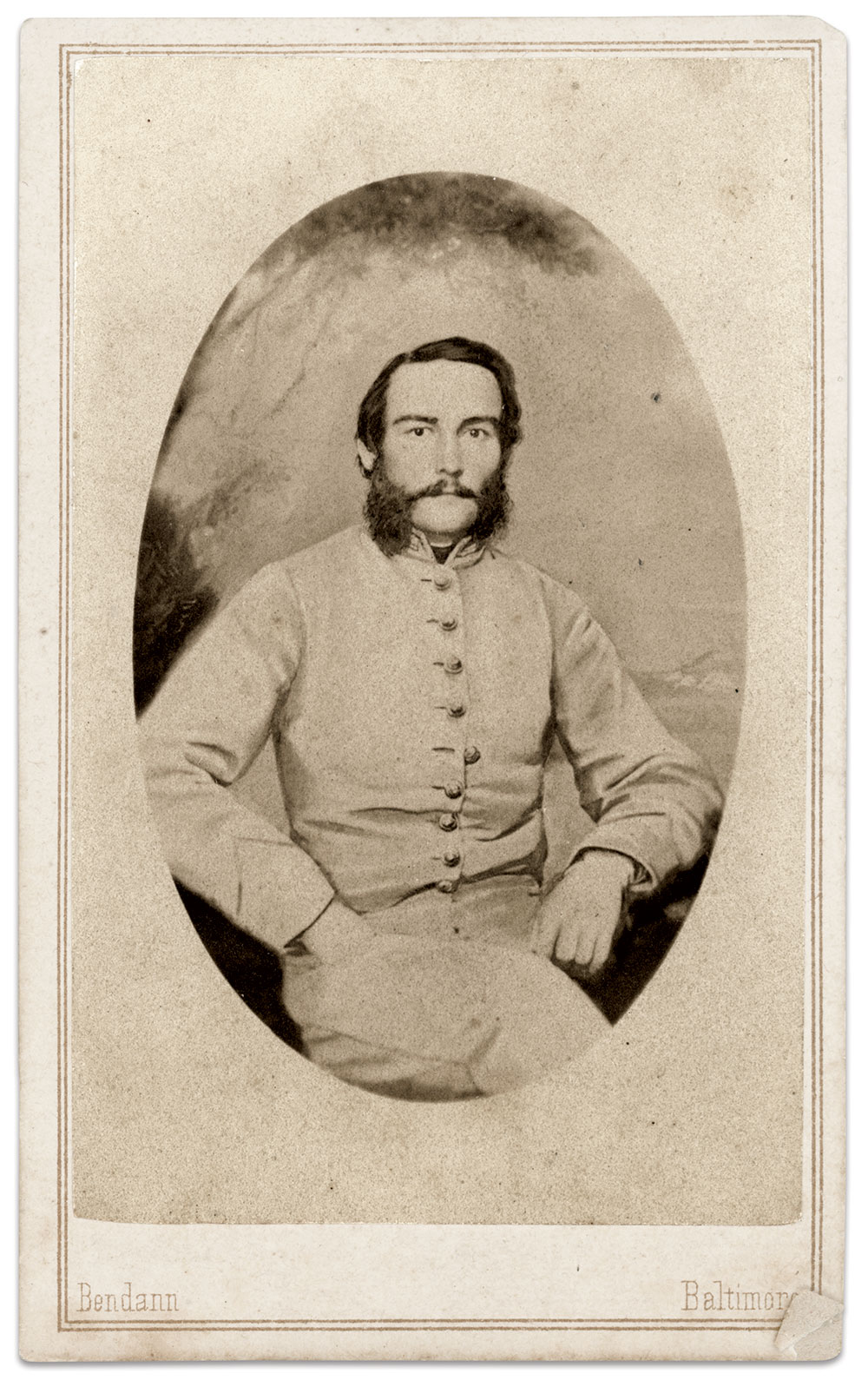

Twice on the Casualty List

As a young man in the 1850s, Thomas Alfred Price left his home in Maryland to join a railroad survey team in North Carolina. When the war began, he lived in Statesville. Price promptly joined his adopted state’s 6th Infantry and fought in the First Battle of Manassas in July 1861, suffering a wound.

Two years later in Virginia, Price became a casualty again. On Nov. 7, 1863, U.S. forces captured him and most of the regiment at the Battle of Rappahannock Station. Transported to Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C., and then on to Johnson’s Island, Ohio, he spent the rest of the war in captivity. He signed the Oath of Allegiance to the U.S. Constitution in June 1865 and gained his release. He returned to Statesville, where he died in 1914, at age 78. He spent his last years at the North Carolina Confederate Soldiers’ Home in Raleigh.

An Inspiration to His Marylanders

When it became clear that Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s massive Army of the Potomac planned to move on Richmond in the spring of 1862, Confederates responded. On April 17, Marylanders struck tents, packed baggage, and marched towards points unknown. Two days later, footsore and hungry, the boys of the Old Line State had become dispirited. One of the commanding officers, realizing it was the first anniversary of the pro-secession riots in Baltimore, relaxed discipline, found a few kegs of drink and boxes of food, and cheered up everyone.

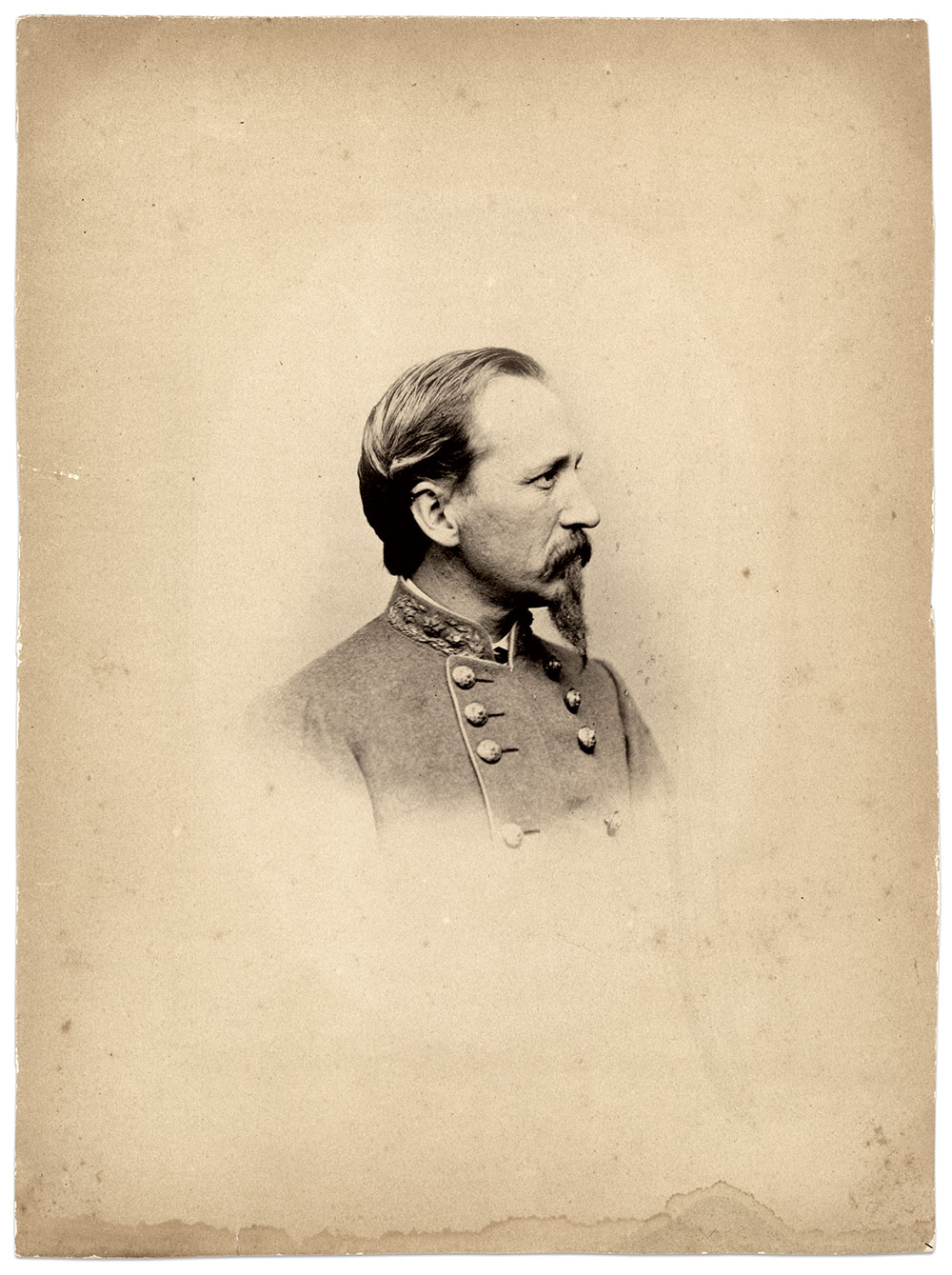

The officer, Lt. Col. Bradley Tyler Johnson, was a fervent supporter of the Confederacy. Born in Frederick and educated at Princeton and Harvard, he equipped a company of soldiers at his own expense and helped organize the 1st Maryland Infantry. A month after the first anniversary of the troubles in Baltimore, Johnson’s regiment defeated Union Col. John R. Kenly and his 1st Maryland Infantry at the Battle of Front Royal, part of Stonewall Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign. Johnson went on to fight in the Peninsula and Antietam campaigns, earn his brigadier’s star, and lead cavalry troops. He also served as commander of the post at the prisoner of war camp at Salisbury, N.C.

After the war, Johnson practiced law in Richmond and Baltimore, and dabbled in politics. He edited Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s memoirs, which were published in 1891. Johnson noted in the preface: “There is a general feeling among our own people, as well as in the country at large, against any reminder of the sufferings of that war, and against any reminiscence, which brings back painful emotions. But it is right and just that our own children should understand the causes of our action, and that they should justify us for resisting such a civilization.”

Johnson lived until 1903. He was 74 years old.

Returning a Captured Sword

In 1894, the townspeople of Bath, Maine, received an unusually-shaped package from a former Confederate officer. Inside, they found a sword engraved “Presented to Lieut. S. Nash by the ladies of Bath” and a letter describing how it had been captured on the battlefield of Resaca 30 years earlier. He noted that now was time to return the sword in the spirit of national unity.

The Confederate, Capt. Charles Stephen Hill, a Baltimorean and graduate of Columbian College in Washington, D.C., had left his job as a bank teller in 1861 to join the army. He served briefly as an officer in the 1st Virginia Artillery before accepting a second lieutenant’s commission in the C.S. Army. He advanced to captain before the end of the year. Thus began a series of ordnance assignments on the staffs of generals William J. Hardee, Patrick Cleburne, Roswell S. Ripley and Nathan Bedford Forrest. Hill received praise from his superiors for his part in the 1863 defense of Fort Wagner and Morris Island, S.C., from the spring of 1863 until its abandonment in September. He then transferred to Cleburne’s staff in the Army of Tennessee. While serving in this capacity, Hill recalled, he had acquired the sword.

Hill’s good-faith return of the sword in 1894 to the people of Bath, Maine, turned out to be a case of mistaken identity. The sword had actually been presented to 1st Lt. Sumner L. Nash of the 163rd Ohio Infantry. He lived in Bath, Ohio. Nash, still alive, claimed to have lost the sword in another action later in 1864.

At the end of his service, Hill returned to Washington and worked as a clerk in the U.S. State Department. His passion for numbers led to his organization of the Census Analytical Association in 1888. It soon became known as the National Statistical Association. Hill died in 1896, widely respected as a government statistician. His wife and several children survived him.

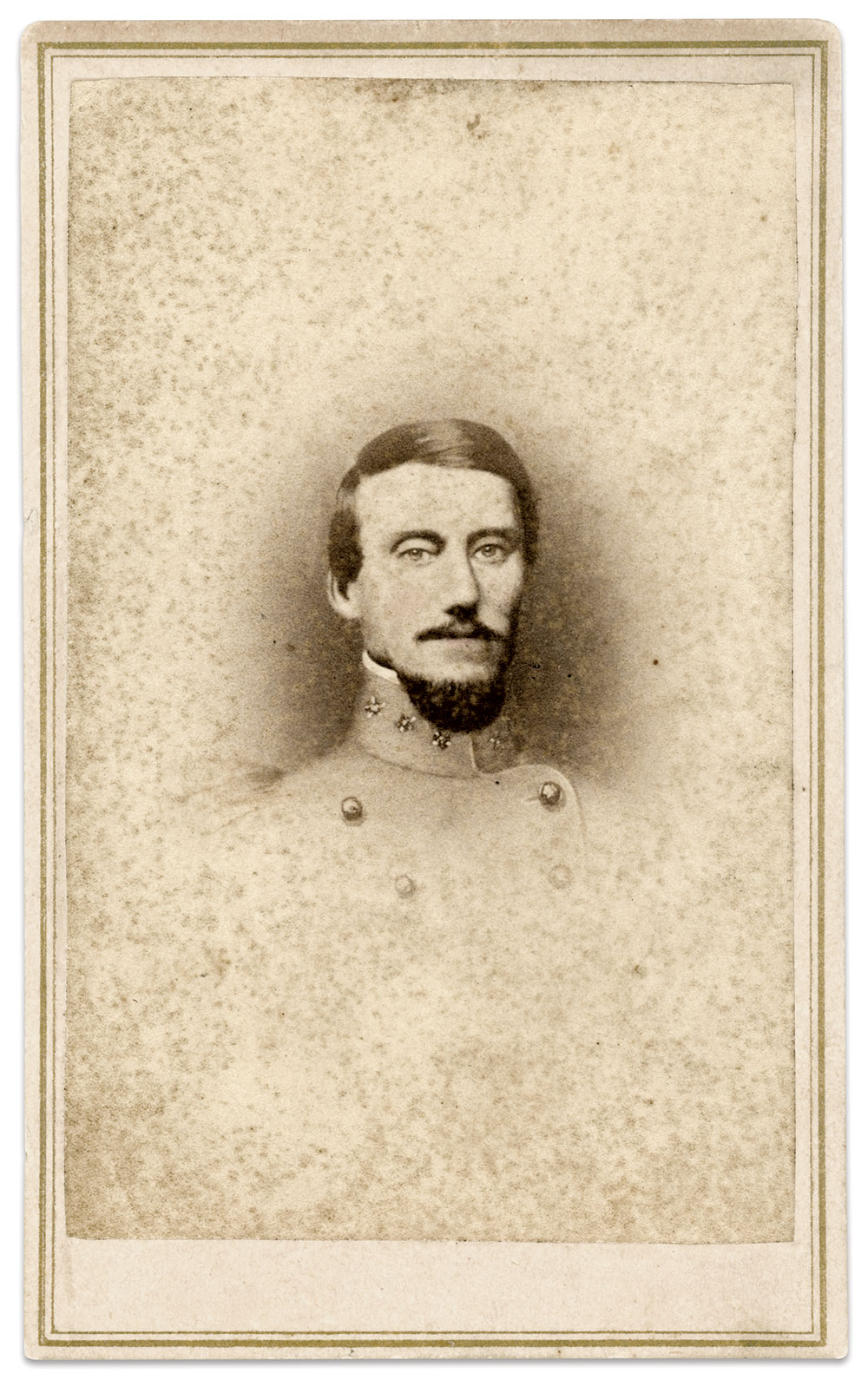

The Heart and Soul of Confederate Maryland

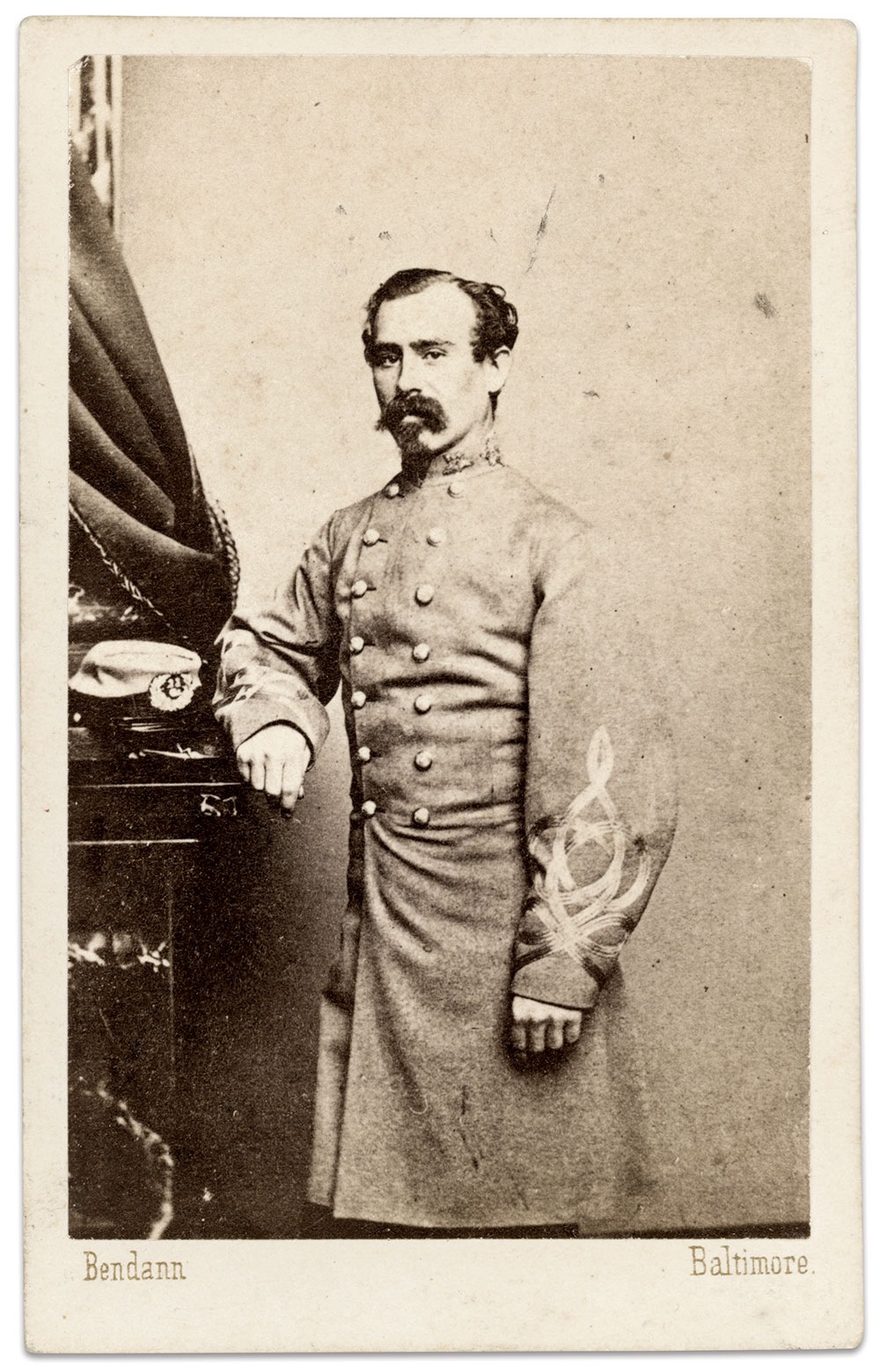

It may be fairly stated that Baltimore’s George Hume Steuart did more than anyone to build a respected fighting force of Old Line State soldiers in the Confederate army. A graduate of West Point Class of 1848 and career soldier, he possessed natural gifts for order and method. When the war came, Steuart left his family estate with his father, a War of 1812 veteran, for the South. Their Baltimore home was seized by the federal government and converted to Jarvis U.S. General Hospital.

In Virginia, Steuart’s father proved too old for active duty. Steuart became the lieutenant colonel of the 1st Maryland Infantry, distinguished himself at the First Battle of Manassas and advanced to colonel. A strict disciplinarian, he whipped his Maryland boys into fighting shape. In early 1862 he received a brigadier general’s commission. He led his Marylanders in numerous engagements, including Stonewall Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign, the Battle of Gettysburg and the campaigns for Petersburg and Richmond, and Appomattox. Along the way, he suffered two battle wounds. Captured at Spotsylvania in 1864, he refused to shake the hand of Union Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, an old army pal. According to one account, after Hancock extended his hand, “General Steuart drew himself up like a private at ‘attention’ and said: ‘I’m sorry, General Hancock, but under the circumstances I cannot accept your hand. I cannot shake hands with the enemies of my country.’”

Exchanged before the summer ended, he returned to his troops and surrendered at Appomattox. He left the army forever known as “Maryland” Steuart to distinguish him from another general, JEB Stuart.

Steuart returned to Baltimore and died there in 1903 at age 75.

Orders Given and Obeyed Cost a Colonel His Reputation

In the thick of combat, split-second life and death command decisions are part of leadership. For Emory Fiske Best, colonel of the 23rd Georgia Infantry his actions at the Battle of Chancellorsville, cost him everything. The Maryland-born son of a wealthy minister who enslaved 20 people, Best moved with his family to northwest Georgia during his youth. Best attended Lebanon College in Tennessee and embarked on a law career.

When the war came, he joined his local militia company, the Floyd Spring Guards, which became part of the 23rd. By the end of 1861 he advanced to major, and following the 1862 Peninsula Campaign received a promotion to lieutenant colonel. He served in this capacity during the Antietam Campaign, which found the regiment engaged at South Mountain and in vicinity of The Cornfield at Antietam. Best suffered a wound and fell into enemy hands. After his release, he returned to the 23rd and became colonel.

The following year at Chancellorsville, U.S. forces caught the Georgians off guard during the early afternoon of May 2, 1863. After skirmishers drove Best’s advance line back, and word came that he was at risk of being flanked, he ordered his men to retire a short distance and took up a new position at a railroad cut. Nearly surrounded, he ordered everyone to fall back. Most were captured. Best and about 40 of his men got away. His escape was interpreted as cowardice by some men who were unhappy with his leadership. Best was ultimately hauled before a court martial for his actions at Antietam and Chancellorsville. The trial failed to prove wrongdoing during the Antietam Campaign but held him accountable for Chancellorsville. He left the army in disgrace.

Best eventually settled in Washington, D.C., and worked as a lawyer for the Department of the Interior. He died in 1912 after suffering a stroke at his office desk.

Cousins Who Made the Ultimate Sacrifice at Gettysburg

Elizabeth Hayden and her son-in-law, Dr. John Reeves, arrived at Gettysburg’s Camp Letterman on a September day in 1863 after a 130-mile buggy ride from Red-House Farm in Southern Maryland. Elizabeth had only recently received word of the whereabouts of her 21-year-old son George, who had been wounded and captured in the recent battle.

George Carpenter Hayden left home in 1862 with other men to join the Confederate army. A letter he wrote referring to “ruthless intruders of Yankeedom” who invaded Maryland reveals the depth of his anger towards the U.S. government. Hayden enlisted in Company B of the 2nd Maryland Infantry and received a promotion to corporal. He served in this capacity, where he suffered a gunshot wound in his left knee during the struggle on Culp’s Hill on July 2-3 and fell into enemy hands. Surgeons amputated his leg at the thigh. He moved to Camp Letterman on August 5 as part of the consolidation of field hospitals that dotted the battlefield.

Hayden’s mother and brother-in-law arrived at Letterman too late. Hayden succumbed to exhaustion on September 23. Elizabeth and Dr. Reeves wrapped Hayden’s body in a blanket and loaded the remains into the buggy for burial in his homeland.

John Alexander Hayden followed his younger cousin George when they left southern Maryland for Virginia in 1862 and joined the army. Hayden also enlisted in Company B of the 2nd Maryland Infantry and fought with his cousin along Culp’s Hill, suffered a gunshot wound in his left shoulder and fell into enemy hands. Admitted to the Union Army of the Potomac’s 12th Corps hospital on July 4, he died there three days later. His burial place is unknown.

Gettysburg Claimed His Life and His Mothers’

The Hagerstown Female Seminary became a hospital for soldiers on both sides wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg. One of the Confederates, William Thomas Blackistone, had suffered a serious wound during the ferocious fighting on Culp’s Hill during the evening of July 2 into the next morning. Family members arrived from St. Mary’s County, on the southern tip of Maryland, to care for their son.

The son of a wealthy and respected attorney, Blackistone entered West Point in 1858 and, though deficient in his studies and conduct, was on track to graduate. Then the war intervened and he resigned to join the Confederate army. In Virginia, Blackistone applied for and received a lieutenant’s commission in the state’s provisional army. But after this organization disbanded as the Confederate army organized, the government rejected a new application based on the grounds that the 19-year-old did not meet the required age of 21. Disappointed but patriotic, he joined the ranks of the 1st Maryland Infantry.

On June 5, 1863, Blackistone, now 21, reapplied for a commission. The application made its way through Richmond’s red tape and received approval on August 18. Blackistone never knew it, having succumbed to his wounds on August 1. His mother, Ann, who nursed him at the Seminary, fell sick and died of disease on August 21. She was 42.

“Don’t Bury me Among the Damn Yankees Here”

On June 15, 1863, Maj. William Worthington Goldsborough and his 2nd Maryland Infantry captured Star Fort, part of the U.S. defenses of Winchester, Va. They took possession of it and about 200 enemy troops. According to one account, among the prisoners was William’s brother, Charles, the surgeon of the Union’s 5th Maryland Infantry. Charles went off to Libby Prison and William continued northward into Pennsylvania.

A couple weeks later at Gettysburg, William led his command into a suicidal charge at Culp’s Hill that devastated the regiment and left him in enemy hands with a life-threatening bullet wound in his left lung. During his recuperation in Baltimore, he met brother Charles, who had been paroled from Libby Prison.

William recovered and joined the prison population at Fort Delaware. Between August and October 1864, he became one of 600 officers sent to Charleston, S.C., and confined in a stockade in the line of enemy artillery fire for 45 days. The men would be forever remembered as “The Immortal Six Hundred.” The federals returned William to Fort Delaware for the war’s duration.

William moved to Winchester, where his brother was captured in 1863, and established the Winchester Times. His account of the war, The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army, was published in 1869. He later settled in Philadelphia. On his deathbed in 1901, William told his wife, “Don’t bury me among the damn Yankees here.” She had his body interred on “Confederate Hill” in Baltimore’s Loudon Park Cemetery.

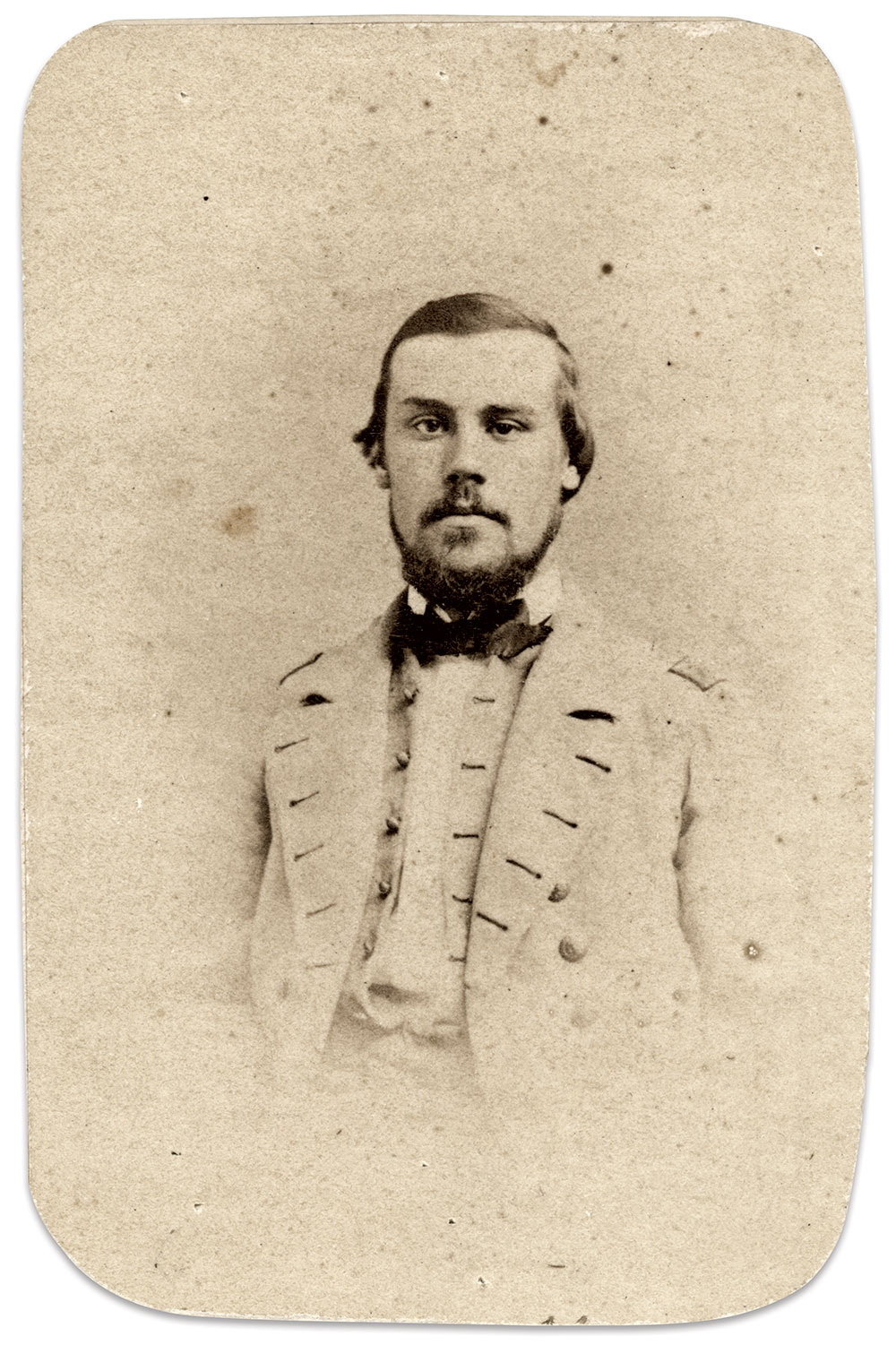

Blockade Runnings by a Baltimore Businessman

The Dare, a sleek Scottish-built blockade runner, met its end on Debidue Beach, S.C., on Jan. 8, 1864. Two U.S. warships, the Montgomery and Aries, had pursued the Dare for about 60 miles before the crew ran it ashore. Bound from Nassau to Wilmington with cargo, federal crews boarded and burned the vessel.

The Dare’s crew escaped. It included Thomas Edward Hambleton, who had traveled to Glasgow to have the Dare built. A 35-year-old native of Carroll County and graduate of St. Mary’s College, he had joined his father’s wholesale dry goods company in Baltimore. In the 1850s, Hambleton and his brother, John, did significant business with Southern firms.

Hambleton left Baltimore in early 1863 for Virginia, enlisted in the 1st Maryland Cavalry, and paid a substitute to replace him. Then he turned to his real objective—selling Southern cotton for munitions. He facilitated contracts between the Confederate War Department and Northern dealers, formed the Richmond Importing and Exporting Company, and arranged the Dare’s construction. Hambleton is also associated with the Coquette, a blockade runner captured in February 1865 as it departed Charleston, where he posed for this portrait wearing a navy officer’s uniform.

Back in Baltimore, Captain Hambleton, as he became known, founded a successful banking house with his brother. Hambleton died a wealthy and prominent man in 1906 at age 78. His obituary in Confederate Veteran magazine observed that his wartime service resulted from patriotic motives rather than personal financial gain.

“I Fight Fairly and In Good Faith”

Colonel Harry Ward Gilmor’s leadership of a battalion of partisan rangers endeared him to his Southern brethren. British by birth and a Maryland Confederate by choice, he proved a thorn in the side of the U.S. Army. Gilmor is remembered for a daring series of raids around Baltimore during Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s invasion of the North in the summer of 1864 that resulted in the Battle of the Monocacy and the Raid on Washington, D.C. In his 1866 memoirs, Four Years in the Saddle, Gilmor recalled meeting Early upon the conclusion of his raid: “When I told General Early with what ease I could have captured Baltimore with a few more men, he regretted heartily that a brigade had not been given me, and he did me the honor to say I had deserved promotion.” Gilmor added that he was offered larger commands, “but I preferred my battalion to any regiment in the army; it was the right kind of stuff, and all I wanted was more of them.”

The federals captured and released Gilmor three times during the war years: as a member of the Baltimore County Horse Guards following the April 1861 pro-secession riots in the city, during the 1862 Maryland Campaign as sergeant major of Col. Turner Ashby’s 7th Virginia Cavalry, and in February 1865 by Union scouts for Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan.

After the war, Gilmor returned to Maryland, where he became a colonel in the National Guard and served as police commissioner and mayor of Baltimore. Cancer took his life in 1883 at age 45. His death made national news and prompted an outpouring of grief by friends, acquaintances and Confederate veterans who appreciated his larger than life presence and the soldierly qualities prominently displayed on the title page of his memoirs: “I fight fairly and in good faith.”

Clubbed by a Musket at Weldon Railroad

U.S. forces seized part of the Weldon Railroad, breaking a critical Confederate supply line, on Aug. 18, 1864. Confederates, including the 2nd Maryland Infantry, attacked the same day to recapture it but were driven back. The Marylanders tried again the next day and in heavy fighting penetrated two blue lines and occupied a portion of the main Union fortifications. Enemy reinforcements counterattacked. In hand-to-hand-combat, a federal used his musket as a cudgel, slamming it over the spine of Maj. James Parran Crane of the 2nd.

Born in St. Mary’s County, Crane studied at the University of Virginia when the war began. He organized and became captain of the University Volunteers. It joined the 59th Virginia Infantry as Company G. The regiment disbanded so that students from outside Virginia could join home state regiments. Crane accepted a captaincy in the 2nd.

Crane’s injury at Weldon Railroad left him partially paralyzed in his left arm and leg and required four months to regain the use of his limbs. He rejoined the regiment in late 1864 and participated in the army’s final engagements, falling into enemy hands twice—the final time when Richmond fell in April 1865.

Crane survived, and eventually returned to Maryland. He practiced law until his death in 1916 at age 77. His second wife, Mollie, and six children survived him.

Brother of a Lincoln Conspirator

George William Arnold Jr. was one of many Washingtonians with Southern sympathies who left in 1861 and joined the Confederate army in Virginia. A Yale educated teacher born in Georgetown, he enlisted in the Engineer Corps and served in Richmond and Norfolk. In late 1862, he transferred to the Nitre and Mining Bureau, a critical agency responsible for supplying copper, lead, and other precious metals for military purposes. Promoted to artillery captain and stationed in Augusta, Ga., he traveled around the South as part of his duties. His two younger brothers, Charles Albert and Samuel Bland, both veterans of the 1st Maryland Infantry who left with disability discharges, appear to have joined him in Augusta as civilian contractors, according to research by author Nathaniel C. Hughes Jr. in Yale’s Confederates.

In early 1864, Charles and Sam returned to Maryland, possibly due to the illness of their mother, Hughes suggests. Arnold resigned and left Augusta with his family for Baltimore before the end of the year.

Following the assassination of President Lincoln in April 1865, authorities arrested brother Sam for his alleged connection to the plot hatched by John Wilkes Booth. A military tribunal found him guilty and sentenced him to life in prison along with other co-conspirators. In the fall of 1865, while Sam languished in prison, Arnold disappeared. A Yale classmate believed he had been murdered. His wife, Elizabeth, and two children survived him. She and her son are buried in unmarked graves in Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington. Her daughter, Fanny, married a Union officer and is buried alongside him in Arlington National Cemetery.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “Divided Maryland: Portraits and personal stories from the Jonathan Beasley Collection”

Comments are closed.