By Patrick Naughton

During heavy fighting along one sector of the Petersburg front on a February day in 1865, a Union lieutenant aided a wounded brother officer. The lieutenant later recalled how he assisted his comrade from the battlefield to an ambulance before returning to his command. The entire event took no less than 15 minutes.

Officers who had performed similar acts of humanity on battlefields across the war-torn South were remembered in official reports and other writings as heroes. But this time, the well-meaning lieutenant was branded a coward, and hauled before a court martial.

His trial offers insights into how leaders treat honor and pride, and how differently soldiers react under combat conditions.

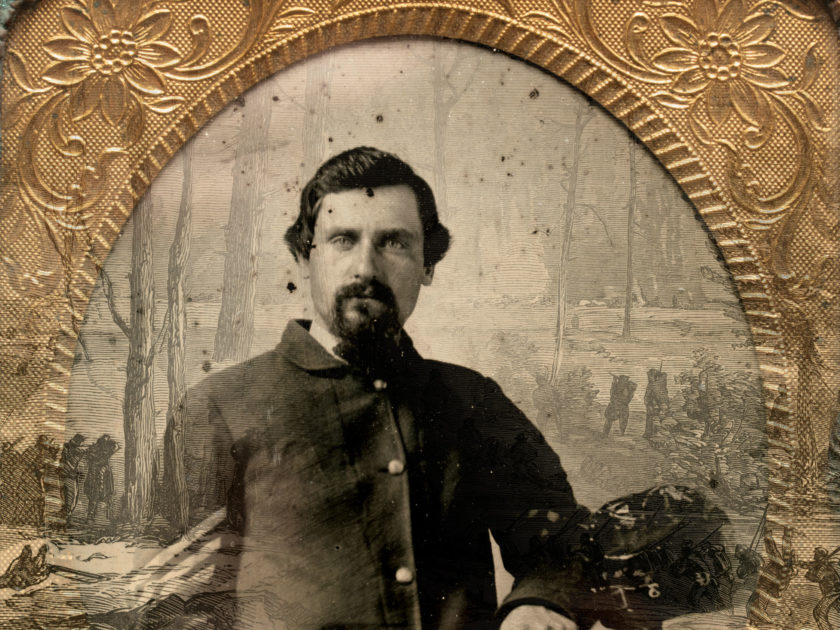

The lieutenant, John Sandford Williams of the 3rd Delaware Infantry, started his service in 1862, working his way from a private to first sergeant before earning an officer’s commission. Along the way, Williams fought in numerous engagements, including Cedar Mountain, Sulphur Springs, Second Bull Run, South Mountain, Antietam, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, Bethel Church and operations against Petersburg and Richmond.

The rescue of his comrade that ended with charges of cowardice occurred during the Battle of Hatcher’s Run, also known as Dabney’s Mill. It was one of numerous offensive operations undertaken by Union forces during the Siege of Petersburg.

The commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, ordered a large cavalry force to sever Confederate supply lines and, as he wrote in his orders, to “take advantage of any opportunity of inflicting injury on the enemy.”

Meade also sent in his Fifth Corps, led by Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, as a blocking force to secure the flanks of the cavalry. Warren and his troops, including Williams and his fellow Delawareans, became engaged in a raging, seesaw fight in front of Confederate breastworks for three days, between February 5 and February 7, 1865. Day One witnessed a lighting advance by Warren’s men; Day Two a humiliating retreat; and Day Three, a return to where they had started.

On that second, dismal day of battle, Lt. Williams commanded the color guard at the head of the Third Brigade of Warren’s Second Division.

Meade, known as the “Old Snapping Turtle” for his irascible manner, bitterly recorded in his dispatches that Warren’s troops were “compelled to retire in considerable confusion.” In his after-action report, Warren acknowledged shortcomings. “I wish to further state that our falling back from Dabney’s Mill under the fire of the enemy was, in my opinion, unnecessary and was against my orders” stated the humbled corps commander, “I believe we can do better next time.”

Warren was less contrite with his subordinates. His Second Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Romeyn B. Ayres, received the brunt of his wrath. “The losses are not sufficient to justify a retreat,” he scolded. Furthermore, Warren claimed, he had issued orders to remain and fight despite the cost.

In his defense, Ayres pointed to the sudden appearance of enemy cavalry that had torn into his lead brigade and swept it away with such ferocity that it took precious time to reorganize his force and continue the advance.

The lead brigade, the Third, was commanded by James Gwyn, a hard-fighting son of Ireland who had earned his way from a company officer in a Pennsylvania regiment to colonel and brevet brigadier general. He acknowledged the cavalry attack which “threw it into such confusion for a few minutes that the brigade never again, through the day, became thoroughly united.” Gwyn claimed that his force had advanced too far forward with unprotected flanks, leaving him vulnerable to the attack that required a retrograde movement of the entire Union line. He also noted the occurrence of several friendly fire incidents that further destabilized the brigade.

In short, he argued, the brigade could not be faulted for the retreat.

The accounts by the top brass were inconsistent with eyewitness reports on the ground.

One officer noted that the Third Brigade men, after receiving what he reported as only some “straggling shots” from the enemy, “became panic-stricken and fled as if by common consent, firing into their officers and among one another as they ran.” A colonel mentioned seeing a mass of troops fleeing through the woods, their colors leading the way. After attempting to order the mob to form and fight, the colonel was greeted by Gwyn in hot pursuit of his own men, who gruffly claimed that “his brigade had broken after receiving but a slight fire from the enemy.”

In a news story headlined “Temporary Defeat of Union Forces,” the New York Times reported, “For a short time it seemed as though a regular panic had seized upon our men.”

In context, Hatcher’s Run, though not a decisive Union victory, achieved some success. A number of enemy supply wagons were seized or destroyed, and Confederate trenches around Petersburg had to be extended, further stressing already strained interior lines.

Back at the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac, Meade suffered a crisis of confidence in his Fifth Corps. “The ignorance I am under of the exact moral condition of Warren’s corps,” he wrote, “and his losses from stragglers, has restrained me from giving him positive orders to attack.” By some counts, almost 600 soldiers from the Fifth had fled and were listed as missing.

Meade acted on his concerns when it came time to man entrenchments to match the Confederate extension. He sent the Second Corps in to occupy them and relegated the Fifth to defend the rear as a punishment for its performance.

With his personal honor and that of the Fifth Corps in question, Warren admonished the Second Division and its Third Brigade. “The brigade left the front without orders and without encountering a sufficient force of the enemy to justify it,” he informed his subordinates. With his positive and clear orders to remain and fight it out, Warren “wished his troops to understand that he will not shield them in his reports. If they won’t fight the country must know it.”

Examples had to be made.

One of the soldiers singled out was the officer who commanded the color company of the lead element of the attack on February 6—Williams. On March 2, 1865, in a makeshift courtroom at the headquarters of the Second Division, a general court martial convened by virtue of Special Orders Number 34 from the Army of the Potomac tried Case Number 16. The court tried Williams on three charges, to which he pled not guilty: conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline, misbehavior before the enemy, and absence without leave.

The prosecution called six witnesses. The first, Manuel Eyre, was the wounded officer Williams assisted. Eyre, first lieutenant and adjutant of the 3rd, acknowledged that Williams helped him to an open field where the brigade commander attempted to reform the unit after its retreat. He added that Williams assisted him 200 to 300 yards further to the rear than necessary, to the actual field hospital—contradicting Williams’ ambulance claim. Eyre closed by noting that Williams then turned back, and that “the engagement, in my opinion, was over at that time.”

The next witness, 1st Lt. William Cloward of the 4th Delaware Infantry, happened to be standing next to Eyre when he was wounded. Cloward could not recognize who had assisted Eyre back to the aide station, but noted that whoever it was, they were gone for up to one half hour. The prosecution asked, “Was there or was there not considerable fighting after that?” Cloward answered that there was, which cast doubt on Eyre’s memory.

The prosecution then called Capt. John Cade, another member of the 3rd, to support Cloward’s statement. Cade testified that he had also been standing next to Eyre at the time of the wounding, and that he exchanged words with Williams. “The accused informed me,” Cade recounted, “that the adjutant was wounded and that he insisted to carry him to the rear.”

Now, Col. Gwyn took the stand. He confirmed Eyre’s story of meeting him in the open field and, due to his wound, gave him permission to go to the rear. After that, Gwyn drew a blank. “When Lieut. Eyre came up and told me that he had been wounded there was no one supporting him,” he informed the court. “I do not recollect having seen the accused at all.”

One of Gwyn’s staffers, Capt. Henry Garothrop, echoed his superior’s testimony. “I know nothing about Lieut. Williams… I do not remember having seen him there at any time.” Garothrop did recall Eyre being aided to the rear but that “two persons, I did not recognize either of them, were assisting him.”

The final witness, Surg. David Wolf, treated Eyre later that night. He described the injury as “rather superficial.”

The defense focused on Williams’ character. The man selected to support Williams, Capt. Dagworthy D. Joseph, was uniquely qualified for the task. He had served with Williams since 1862 and had been singled out by Gwyn for heroism at Hatcher’s Run. Joseph recounted the numerous engagements in which he and Williams had fought together and informed the court that the accused had always done his duty as a soldier. Looking toward his comrade in the courtroom, Joseph confidently declared, “I have never known anything derogatory to your character as an officer and a gentleman.”

Williams’ written defense, submitted to the court and entered as Exhibit A, highlighted his rise from the ranks to company officer. He then told his version of events at Hatcher’s Run, explaining that at the time of Eyre’s wounding the brigade was already retreating. Eyre grasped Williams’ arm in a panic, crying, “I am wounded, I fear near the heart!” Williams, in the act of rallying the troops after the enemy stopped their advance, abandoned the effort and carried Eyre to an aid station located in an open field, where the brigade attempted to reform.

“During this time, I was engaged in a humane act,” Williams informed the court, “not thinking that I was committing a wrong.”

In the open field, Eyre clutched and begged Williams to take him to the field hospital, exclaiming, “I am getting very weak.” Williams, unwilling to go that far, assisted him to an ambulance staged near the front, at which point he returned to his command. He claimed he was gone no more than fifteen minutes. “During this time, I was engaged in a humane act,” Williams informed the court, “not thinking that I was committing a wrong.” Concluding his entreaty to the court, Williams left the case in the court’s hands, believing that they would do him justice.

A panel of eight officers from the Division deliberated the case and passed its verdict: They found Williams guilty on all charges and sentenced him to immediate dismissal from the army.

But there was a twist. The same panel recommended his sentence be remitted. They issued a signed joint letter to show him mercy. “On account of the long service and ferocious good character of the accused,” wrote the panel members. “Lt. Williams’ offence, grave as it was, was not committed through cowardice, but from less disgraceful motives.” Maj. Gen. Ayres endorsed the request.

The request wound its way through the chain of command to the highest level of the Army of the Potomac. Roughly hand-scrawled and signed by Maj. Gen. Meade in the vertical margin of the original court transcripts, it reads: “In consideration of the recommendation of the court the sentence is remitted.”

The trial record lacks a mention that Williams himself suffered a wound at Hatcher’s Run. A spent round had struck him in the lower right leg just above the ankle.

Williams went on to serve with distinction and fought with his regiment until the end of the war, which included leading his company during the Grand Review of the Armies in the nation’s capital in May 1865.

Back in Delaware after he mustered out, his injured foot became ulcerated and the veins enlarged. The pain plagued him for the rest of his days, so much so that he could no longer work in his profession as a painter. He received a disability pension from the government, which helped him support his wife and seven children. Williams died of liver cancer in 1897 at age 63. His remains rest in Riverside Cemetery in Trenton, N.J., his birth state.

Williams’ family remembered him as a hard-working family man who, despite the physical pain he suffered every day, took great pride in his service to his country. As the family’s American Revolution veterans were to him, he set an example for scores of his descendants who have since served with honor in almost every American conflict since the Civil War.

References: Official Records, Proceedings of a General Court Martial, Convened at Headquarters, Second Division, Fifth Corps, March 2, 1865, File # 00-0587, National Archives, Washington, D.C. John S. Williams military service and pension files, National Archives, New York Times, Feb. 10, 1865.

Patrick Naughton is a Medical Service Corps U.S. Army officer and a military historian. He currently serves as a Legislative Liaison to the U.S. Senate in Washington, D.C. Naughton is a recipient of the General Douglas MacArthur Leadership Award, a former Interagency Fellow, and a Congressional Partnership Program Fellow with the Partnership for a Secure America. He holds a Master of Military Arts and Science degree in History from the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, where he was an Art of War Scholar, and a Bachelor of Arts degree in History from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. His writings have appeared in Military Review, InterAgency Journal, Joint Force Quarterly, the Journal of America’s Military Past, the Journal of the American Revolution, and the National Defense University. The views expressed here are those of the author and not of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or any agency of the U.S. Government.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.