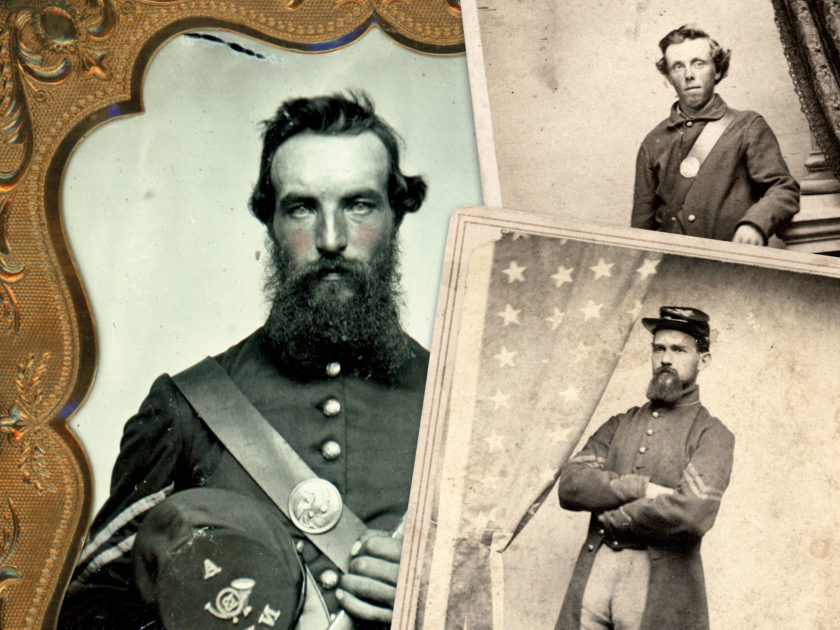

The Granite State’s contribution to the Union army is as remarkable as the unique NHV insignia worn on the caps of its volunteers.

More than one in 10 New Hampshire men served—35,000 strong formed in more than two dozen military organizations. Eight of the state’s infantry units were enshrined in the list of “Three Hundred Fighting Regiments” compiled by William F. Fox in his landmark treatise Regimental Losses in the American Civil War.

At Gettysburg, 900 New Hampshire men fought, with 368 becoming casualties. One of the regiments present, the 5th New Hampshire Infantry, suffered the most battlefield deaths of any Union regiment during the entire war. Sacrifices by the 5th and their brothers in blue restored the Union, saved the Republic, and ended slavery.

Granite State veterans left behind monuments and memorials, regimental histories, related books and articles, and a mountain of personal papers, including the photographs shown here. A representative group of soldier portraits, all identified and accompanied by accounts of their lives and service, cast a spotlight on New Hampshire’s role in the Civil War.

The Advance of the 50

Port Hudson is remembered for the surrender of its Confederate garrison after its position became untenable five days after the fall of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. The anticlimactic conclusion at Port Hudson belied numerous courageous acts performed during the Union siege of the rebel stronghold.

The regimental historian of the 15th New Hampshire Infantry described one such event as “The Advance of the 50.” On June 13, 1863, five men from each company in the regiment joined the same number of infantrymen from the 26th Connecticut to determine the strength of the heavily defended rebel fortifications in their front. They made it within 200 feet of the parapet of Battery 16 before overwhelming fire stopped their advance. They held the position until nightfall.

One of the trapped men, 1st Lt. Alfred B. Seavey of Company H, took cover behind an old tree stump with a sizable tangle of exposed roots. As the hours passed, enemy fire riddled the roots and the stump without wounding him. At one point, one of his men, located directly to his left, was threatened by a lone Confederate that fired shots at him. Seavey asked his exposed comrade for his rifle, and the man complied. Seavey then poked a hole through a rotted section of the stump, took aim and fired a single bullet into the sand bags from which the shots came. The rebel fired no more.

When truce flags later went out to care for wounded on both sides, the color bearers met near the stump. The Confederate, a major, inquired who was behind the stump with a rifle. Seavey identified himself, and was informed by the officer that the single bullet he fired struck and killed a respected rebel sergeant.

Seavey survived the day. Two of his command died, and six were wounded. Port Hudson fell weeks later, and soon after the 9-month enlistment of the 15th ended.

Seavey returned to his occupation as a harness-maker in Gilford, N.H., and reunited with his wife, Ellen, and a daughter. He did not enjoy peace for long, dying in 1871 at age 42.

Close Call at Port Hudson

By all accounts, the closest Albert Franklin Brown Edwards came to meeting his end in the war occurred in Louisiana during the Siege of Port Hudson. “Edwards was here under fire, but marvelously escaped injury when the barrel of his gun was burst by a passing ball,” noted one writer in a post-war biographical sketch.

Edwards, a member of Company K of the 15th New Hampshire Infantry, a 9-months regiment organized in late 1862, spent the majority of his enlistment in the environs of Port Hudson as a corporal and sergeant. Though the biographer did not note the exact date of Edwards’ close call, it may have occurred in one of the battles fought on May 27 or June 14, 1863. A month after the surrender of the Port Hudson garrison, Edwards and his comrades mustered out of service. He returned to the army in 1864 with the 18th New Hampshire Infantry, and participated in the Siege of Petersburg.

After the war ended, he became a farmer and lumberman. Active in veterans’ groups and local politics in Chester, N.H., he died in 1925 at age 81. His second wife and several children survived him.

Eventful Furlough

In July 1864, after more than two years actively engaged in Louisiana, the veterans of the 2nd New Hampshire Cavalry left for a month-long furlough in the Granite State. Their number included Cpl. William H.H. Fernald of Company G. A farmer in Dover, N.H., Fernald had participated in his share of fighting, including the failed assault against the formidable defenses of Port Hudson on June 14, 1863, during which he suffered a wound in his foot.

Fernald and his comrades belonged to the 8th New Hampshire Infantry (with the exception of the period December 1863 to July 1864, when military authorities converted the 8th to mounted infantry). They were designated the 2nd New Hampshire Cavalry from March through their furlough in July 1864. The hat brass and the photographer’s Dover backmark date this portrait to his furlough. Dan Miller, author of American Zouaves, 1859-1959, observed that Fernald’s uniform includes “some purely Zouave inspired details—the tombeau on the chest—but the rest of the uniform is more of a chasseur as it buttons up and has a collar.” He suggests that the regiment may have been inspired by other regiments serving in the Gulf region, specifically the 48th Ohio, 34th Indiana, and 4th Iowa infantries.

The significance of the seven-pointed star, perhaps knit or crochet, worn on his chest is unknown. It may be related to his marriage to Laura J. Canney, which took place Aug. 11, 1864, about the middle of Fernald’s furlough.

Fernald rejoined his regiment in the Gulf after the end of his break and served through October 1865. He returned to his newlywed wife and farmed until his death at age 43 in 1885. Laura lived until 1935. She never remarried.

Detailed as a Nurse in Louisiana

Soon after he enlisted in the 15th New Hampshire Infantry, Pvt. Mark Hunking Winkley was detailed as a hospital nurse. There’s no evidence that the 26-year-old peacetime farm laborer from Strafford, N.H., had experience as a caregiver. But his record suggests he was well suited to the task, as he served in this capacity with the 15th in Louisiana until he mustered out at the expiration of his 9-month term in August 1863. Winkley’s dedication to duty with the sick and wounded took a toll on him, and he became hospitalized after developing chronic rheumatism during his final months in uniform. His illness continued after his return home, and he died at Strafford on April 17, 1867, at about age 31. His wife, Sarah, and three children survived him.

A Family Visit Ends with an Enlistment

While on a visit to relatives in New Hampshire in 1862, Illinois-born and raised Henry F. Partridge joined the army. He is pictured here after his enlistment in the Granite State’s 9th Infantry, displaying his cap with the letters of his adopted state. He wears a Model 1855 rifle belt, with a hunting knife and revolver tucked into it, and is armed with a Model 1841 rifle.

The 9th spent most of the next three years in the Eastern Theater, with the exception of a yearlong stint in Mississippi to participate in the Siege of Vicksburg. Partridge advanced to sergeant along the way and suffered wounds in two 1864 Virginia battles. At Petersburg on June 18, a ricocheting cannon ball struck him on the right hip and knocked him out. Presumed dead and carried to the rear, he regained consciousness and spent a few months in the hospital. Shortly after his return to the ranks in September, he suffered a gunshot wound in the opposite hip during the fighting at Poplar Springs Church. This injury ended his combat service, and resulted in his discharge in May 1865. According to the regimental historian, Partridge “enjoys telling the story of how the Confederates wasted their lead.”

In 1867, Partridge relocated to the village of Winchendon, Mass., and went into the contracting and building trade with George C. Willson, an old army buddy who served alongside him in Company I. Partridge lived a long life, dying at age 96 in 1935. He served as commander of his local Grand Army of the Republic post before his passing. Partridge outlived his wife, Susan, and most of his comrades, including Willson, who had died in 1914. Partridge died in the home of Willson’s son, Edgar.

Wounded during the Battle of the Mine

Capt. Matthew Nolan Greenleaf and his comrades in the 6th New Hampshire Infantry were a short distance behind the front line when the detonation of a mine left a massive crater in the Confederate defenses at Petersburg, Va., on July 30, 1864. As the first line of troops advanced, the Granite Staters took their place and waited for orders. When rebel artillery rained down upon them, they appealed to their brigade commander, Simon G. Griffin, to let them join the fray. The request was denied as too many men already occupied the crater. The fire intensified, and the request renewed. Griffin relented, ordering the 6th to advance into an open field close to the crater and await further orders. This move proved even more dangerous for the men, who eventually withdrew with the remnants of the battered Union army.

Greenleaf numbered among the wounded. A silversmith born in Massachusetts, he had started his war service with a 3-month enlistment in the Bay State’s 5th Infantry. He joined the 6th as first sergeant of Company C in October 1861 and steadily advanced through the ranks. He received his captain’s bars and command of Company H less than a month before the Battle of the Crater. His injury ended his service and he left the regiment with a disability discharge before the end of the year. Greenleaf died at age 39 in 1873. His wife and a son survived him.

Pioneer Gettysburg Battlefield Guide

One day in the autumn of 1890 in Gettysburg, a group of Marylanders set out for a tour led by Charles Austin Hale, a popular battlefield guide. Hale, a lecturer and authority on Paul Philippoteaux’s Cyclorama painting, had firsthand knowledge of the three-day fight.

More than a quarter-century earlier, then 2nd Lt. Hale and his comrades in the 5th New Hampshire Infantry, 182 strong, led the counterattack in The Wheatfield during the afternoon of July 2. In two hours, it lost about 45 percent of its numbers. Hale survived without injury and received a promotion to first lieutenant.

Hale had not been so lucky in previous engagements. The Maine-born son of a minister had suffered two slight wounds since his 1861 enlistment. As a color sergeant at Fredericksburg, a comrade recalled asking him, “Who will care for the flag?” as he was carried off the field of battle. He suffered another injury as a second lieutenant at Chancellorsville.

The cumulative toll of fighting compromised Hale’s health. The 5th went down in history as having suffered the most battlefield deaths of any Union regiment. He resigned a month after Gettysburg and found employment in Washington, D.C., as a War Department records copyist. He returned to the regiment in early 1865, received his captain’s bars, and mustered out at the war’s end.

Hale went on to marry and work as a machinist in New Jersey before becoming involved with the Gettysburg Cyclorama and, later, with tours of the battlefield. Though not the first professional guide at Gettysburg—this honor falls to Sgt. William David Holtzworth of the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry according to The Association of Licensed Battlefield Guides—Hale’s pioneer work contributed to the high standards for which today’s guides are recognized. He worked closely with the Tipton brothers, who held a virtual photographic monopoly in Gettysburg throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1899, Hale died at age 58 after a brief illness.

Reaching for the Colors at the Klingel Farm

The 12th New Hampshire Infantry marched into Gettysburg commanded by a senior captain after its field officers had all been lost a month earlier at Chancellorsville. On July 2 during heavy fighting north of the Klingel Farm against Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox’s Alabama Brigade, there came a moment when the color sergeant of the 12th suffered a mortal wound. Granite State boys rushed to his aid. As the sergeant’s grasp of the Stars and Stripes slipped away, Cpl. Samuel Brown reached out to keep the banner from falling.

Brown, pictured here, had started his service as a private in Company C, and suffered a hip wound in the recent action at Chancellorsville. His older brother, Caleb, fought in Company D.

As Brown reached out for the flag at Gettysburg, he was struck by rebel lead in the bowels. Carried to a field hospital in the evening, he succumbed to his wound while being removed from an ambulance. He was 21. Gettysburg also proved to be brother Caleb’s last battle. Suffering from chronic diarrhea, he was sent to Baltimore, where his father took him to New Hampshire to recuperate. He died about a week later.

From Corporal to Captain

In late 1864, Capt. Jasper Warren and two companies of the 25th U.S. Colored Infantry helped keep the peace in Union-occupied West Florida. Warren, a 33-year-old carpenter and married father of two from New Hampshire, had started his military service two years earlier as a corporal in Company A of his home state’s 13th Infantry. About a month after the regiment fought its first major engagement at Fredericksburg in 1863, Warren earned his sergeant’s stripes. When an opportunity came for advancement as an officer in the U.S. Colored Troops, Warren seized the opportunity, and received a captain’s commission in the 25th infantry in early 1864. He spent the rest of the year in the Department of the Gulf. His time in command in the western part of Florida numbered among his last assignments before mustering out in December.

Warren returned to New Hampshire and life as a carpenter. Following the death of his wife, Olivia, in 1867, he remarried and became the father of three children that all died young. Active in civic affairs in Wolfeboro and the Grand Army of the Republic, Warren died in 1912 at age 81.

The Redoubtable Ayer

Age has its advantages. According to the historian of the 3rd New Hampshire Infantry, Capt. Henry Harrison Ayer “had more influence over a squad of men than many a younger officer, because of his age, firmness and sternness, with all that goes therewith.”

Ayer, a 42-year-old cabinetmaker born in New York, brought a host of eccentric behaviors and peculiar personality traits detailed by the historian. A genuine character in his Company B and throughout the regiment, Ayer possessed courage to match. Injured by a spent musket ball during the July 18, 1863, assault against the garrison of Fort Wagner, S.C., and, a month later by another ball that passed through his neck near the spine and base of his skull, he recovered and fought on with his command. Less than a year later at Drewry’s Bluff, Va., another rebel bullet tore through his thigh and nicked the femoral artery, causing his death. Wrapped in a rubber blanket and buried in a hastily dug and marked grave, his remains were later recovered and reinterred in a cemetery in Penacook, N.H. His wife, Jane, and two children survived him. Thus ended the life of a man referred to by the regimental historian as “the redoubtable Ayer.”

Likeness at Fort Richardson

Fort Richardson, located along a crest southwest of Alexandria, Va., marked the highest point of the Arlington line of the defenses of Washington, D.C. Boasting 15 guns and a garrison of more than 400, it sat adjacent to a sprawling military encampment. At some point, a photographer named Cross set up shop in the vicinity and engaged in brisk business, as evidenced by the surviving number of cartes de visite.

Charles H. Johnson numbered among the soldiers that stopped by the gallery to preserve his likeness during the war’s waning months. A private in Company E of the 1st New Hampshire Heavy Artillery, he joined the regiment in late 1864 and traveled with his comrades to the nation’s capital. There, they garrisoned a 10-mile stretch of the city defenses, and performed picket duty through the remainder of the war.

Johnson mustered out with his fellow artillerymen in June 1865, and returned to wife, Sarah, and children, whom he supported as a farmer. Upon Sarah’s death in 1883, he married twice more. Johnson succumbed to complications of a stroke in 1919 at age 78.

He Barely Enjoyed Peace

Some fortunate soldiers survived their enlistment in a hard-fighting regiment without suffering a wound in battle. Such was the case for William P. Mason, a farm laborer who served as a private and corporal in Company F of the 12th New Hampshire Infantry. The regiment participated at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and numerous engagements during the 1864 Overland Campaign. The regimental historian stated of his service, “He fought on many battle-fields of his country, and was not discharged until his country’s foes had grounded their arms, and peace once more assumed her rightful sway over a land that had drank up some of the best blood of the nation.”

Mason barely enjoyed the peace. Two years later, in 1867, he drowned while bathing in a pond with two friends near St. Charles, Minn. He was 25.

What Maurice Saw

On June 15, 1864, in the vicinity of Petersburg, Va., Pvt. Maurice S. Lamprey recorded the events of the day in his diary. He noted menacing, dark clouds of dust stirred by Confederate soldiers marching to reinforce the city, a general’s order, and more. He could not have imagined that this entry would be published 40 years later in newspapers across the country.

Born in New Hampshire, his deeply religious farmer-father, Ephraim, became the first proclaimed abolitionist in Groton. His mother, Bridget, took a great interest in women’s suffrage. In the 1860 census, Lamprey worked as a varnisher. Evidence suggests he became a photographer at some point after. In the summer of 1862, he joined his native state’s 10th Infantry. Four of his brothers also fought for the Union, and one died as a result.

In November 1863, Lamprey transferred to the U.S. Signal Corps as a private. Seven months later in Virginia on June 15, 1864, he and his comrades kept communications flowing from the signal tower on Cobb’s Hill, which had a commanding view of Petersburg. On that day, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler ordered an attack on the city before Gen. Robert E. Lee could send reinforcements. One of Butler’s subordinates, Maj. Gen. William Farrar “Baldy” Smith, succeeded in taking a portion of the enemy’s first line of defenses, but reportedly failed to push the attack. The resulting delay allowed time for Lee’s troops to entered Petersburg and hold on for nine months, until forced to abandon the city on April 2, 1865.

Butler relieved Smith from command a month later for lack of aggression, and other issues. Smith believed he had been wronged, and went to his grave in 1903 unable to clear his name. Following his death, a Signal Corps sergeant went public with a letter that held Butler responsible for stopping Smith shy of the city. The sergeant included Lamprey’s June 15 diary entry as evidence. It included these lines that implicated Butler: “Sent message to Gen. Smith to entrench at once and hold his position; guess that Gen. Butler is getting rattled over the dust that the ‘Rebs’ are kicking up; desultory firing.”

Lamprey mustered out of the army in June 1865 and returned to New Hampshire, where he practiced photography for many years. The image here, backmarked with the name of his gallery, suggests this is a self-portrait. He died in 1912.

Three Months a Soldier

On Sept. 26, 1862, the day before leaving the New Hampshire capital for the South, the men of the 12th New Hampshire Infantry made their final departure preparations. In the ranks of Company F, Stephen Wells Batchelder made out his will. He left everything he owned, plus any pay and bounty money due him, to his wife, Mary. They had married several years earlier.

Batchelder might have been concerned about his health. At 42, the peacetime farmer from Loudon, N.H., was old enough to be the father of many younger men in his company when he enlisted in August. Any fears he might have had were realized soon after the regiment’s journey began. On Nov. 16, 1862, after an approximately 16-mile march between the Virginia villages of Waterloo and Washington, an ill Batchelder was loaded with other sick men aboard a train bound for Washington, D.C. He died en route. His military service lasted all of three months.

An Assignment in Washington

Minor events can shape life in unexpected ways. Cpl. Henry Garland Ayer of the 1st New Hampshire Cavalry had such an experience in the fall of 1862 when detached from his company to serve as clerk to the regimental quartermaster. He performed well in his new duties. When the quartermaster received an assignment on the brigade level, he took Ayer with him. Ayer eventually moved to the Cavalry Bureau in Washington, D.C., where he remained until November 1864, when his term of enlistment expired. At this point he took on a new assignment—husband.

Days before his discharge, he married Sarah E. Shields, a Washington native. He worked as a clerk in the Treasury Department and later the Pension Bureau to support Sarah and, beginning in the late 1860s, the first of three children. Ayer died at age 50 in 1889 from peritonitis. Sarah joined him in death six years later. They lie buried alongside two of their children in Congressional Cemetery.

Thanksgiving, 1862

On Nov. 27, 1862, Pvt. William Thorp celebrated Thanksgiving by posing for his likeness. He did so in a studio not far from the encampment of his regiment, the 16th New Hampshire Infantry, at Park Barracks in New York City. He and his comrades had arrived a few days earlier from the Granite State on the first leg of their journey to the seat of war. Most of the men were wowed by the sights and sounds of the city, and far less enthusiastic about the poor quality of Thanksgiving dinner supplied by dubious contractors.

For Thorp, a 39-year-old native of Derby, England, who had arrived in America during his youth, this Thanksgiving was likely the first away from his wife, Almira, and four children at home in Weare, N.H.

It was also his last Thanksgiving. Less than a year later, he succumbed to chronic diarrhea in a military hospital at Mound City, Ill. Almira raised the children with the assistance of her late husband’s pension. She never remarried, and lived until 1918.

A Birthday to Remember

On May 8, 1863, Charles A. Place marked his 21st birthday in a decidedly un-celebratory manner: He entered Libby Prison as a guest of the Confederate army. Five days earlier, Place and his pards in the 12th New Hampshire Infantry fought in the thick of the action at Chancellorsville. Place fired 60 rounds, when, he recalled, “my gun became so foul that I could not drive a charge home, so I forced the end of the rammer against a small tree close by. As we fell back to avoid capture by one line of the enemy we found ourselves in the rear of another, and could do nothing else but surrender.”

Place’s time at Libby Prison and Belle Isle was relatively short compared to other prisoners of war. His captors released him 17 days after he entered Libby, but he never forgot the experience. The following year at Petersburg, when in harm’s way, he took great pains to avoid capture, which included risky exposure to rebel bullets.

Place had started his service as a private in Company A. He advanced to first sergeant, and received a promotion to second lieutenant during the war’s last weeks, but never officially mustered out at this rank. After the regiment completed its enlistment in June 1865, Place returned to New Hampshire and married Abbie Cate, the sister of one of his comrades. They started a family that grew to include three children. He supported them as a traveling salesman. Place lived until age 71, dying in 1913.

Among the Last Volunteers

Federal government calls for states to supply men for military service continued into late 1864, and New Hampshire was no exception. In Conway, located near the White Mountains and the Maine border, civic leaders encouraged volunteerism with $800 (about $13K today) to avoid the indignity of a local draft. Among those who volunteered was 23-year-old clerk George H. Thom. He became a second lieutenant in Company E of the 18th Infantry, the last organized unit in New Hampshire.

According to a historical sketch, “The members were almost entirely citizens of the State. A good many of them had seen service in other organizations, and the remainder were good men, whose delay in volunteering may fairly be presumed to have been justifiable.” Thom was in the latter category. He spent a few months with the 18th in the defenses of Washington, D.C., and at the front lines of Petersburg, before he resigned due to disability in mid-March 1865. The 18th went on to fight in two of the war’s few remaining actions in Virginia, the Battle of Fort Stedman, and the final assault against Petersburg.

Thom resumed his life as a clerk and moved to Chelsea, Mass., where he died of apoplexy in 1899 at age 58.

In the Attack of Grover’s Brigade

The regimental historian of the 2nd New Hampshire Infantry wrote with evident pride about the advance against rebel infantry during the Second Battle of Bull Run.

“Shocking the first line of Confederates entrenched along a railroad embankment, savage hand-to-hand fighting broke the second enemy line but scattered their own forces. The loss of momentum at the third line that ended in a withdrawal.” The other regiments involved in the attack, part of the brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Cuvier Grover, did not make it as far as the 2nd.

The historian also detailed the losses suffered, including 1st Lt. Sylvester Rogers. A medical student in Nashua when the war began, he had helped examine recruits in the wake of Fort Sumter before joining Company G in May 1861.

At Second Bull Run, Rogers reportedly had advanced deep into the rebels’ third line when a musket ball shattered a knee. A comrade lifted Rogers and urged him to move. Another jumped in, and the two men carried the lieutenant as far as the railroad embankment, where another bullet tore into the small of his back above a hip. “Cheer up, Rogers, we will carry you safely out of this,” said one man. Rogers replied with a groan and a gasp before falling forward in death. Buried on the battlefield in an unmarked grave, Rogers’ remains were never recovered.

A month later, mourners gathered at the Universalist Church in Nashua to honor him. Denied a proper funeral, the presiding minister observed, “We can only think of him, as resting where he fell, hastily buried upon the bloody field. Far away, beyond the Potomac, we may imagine him sleeping among the undistinguished thousands who fell upon that fatal day, the 29th of August. The place has not the quiet beauty of our cemeteries. You may see there the long ridges of freshly heaped earth, where the slain are buried. The trees are scarred and torn by the shot, and the ground is still gashed by the wheels of the artillery and the hoofs of war-horses. There he lies, having fought a good fight and done noble service for our country and for us all.”

The minister continued, “We have now only to imitate the gentle ministry of nature. For mark!—another Spring will sweeten that bloody field with the breath of flowers, and with delicate fingers will cover the unsightly work of human passion, and will extract beauty even out of the bosom of decay. And may the Infinite Lord of pity as gently heal the wounded hearts that bleed to-day and in every nook and corner of memory and affection sow the seeds of healing and consolation to bloom towards heaven.”

Four Wounds in Five Months

During its three years, the 11th New Hampshire Infantry spent as much time as any regiment wiling away hours in camp. Among those Granite State men that made the long periods of inactivity tolerable was one of its finest singers, Jacob Le Roy Bell. A farmer’s son born and raised in Haverhill, N.H., Bell helped recruit local men for the army in 1862. They became part of Company G of the 11th. Bell joined them as second lieutenant and later advanced to captain. The regiment spent much of 1863 engaged in the sieges of Vicksburg and Knoxville. Bell emerged from these operations without injury.

The year 1864 proved quite different for him.

Sent to Virginia with the rest of the 11th, Bell received four wounds in the space of five months. In May at Spotsylvania, he suffered a minor injury in the left leg. A bullet left him with a scalp wound near Bethesda in June. Another bullet resulted in a minor head injury at the Battle of the Crater in July. In September, a Minié ball tore into his right thigh during the fighting near Poplar Springs Church. The last wound ended his combat service, and he spent the rest of the war recuperating on light duty in Concord, N.H. He is pictured here about this time wearing mourning crepe in memory of President Abraham Lincoln.

Bell returned to Haverhill at the conclusion of his service, and made a comfortable living as a grocer. He married and outlived two wives before suffering a life-ending cerebral hemorrhage in 1916. He was 76.

The Marker

In the Granite State’s 12th Infantry, also known as the “New Hampshire Mountaineers,” Frederick S. Morse did measure up to the moniker. Boyish looking and all of 17 when he enlisted in Company F, “he was selected as a ‘marker’ early in the service, carrying a small flag instead of a gun,” in drills, noted the regimental historian. Never joining the line of battle, the jolly-hearted teenager became an orderly to the colonel—and quite the trickster. One veteran remembered how he “always greeted you with a roguish grin suggestive of the joke or prank that was pretty sure to follow; and then he would run away with an explosive laugh that would sound something like the bursting of a coehorn mortar shell.”

The same soldier recalled how Morse begged to fire a shot at the rebels from the trenches of Petersburg during the grueling summer of 1864. Handed a loaded rifle, he poked it through a hole in the earthworks. As he took aim and prepared to pull the trigger, a bullet from the other side tore into the rifle and destroyed it, sending stock and lock splinters through his cap and hair. His sober face generated an abundance of laughs and jokes from his pards.

Fun-loving Morse ended his enlistment when the regiment mustered out in June 1865. He eventually made his way to Massachusetts, married, and worked as a painter for a carriage manufacturer and an ice company. Active in the Grand Army of the Republic until his death in 1911 at age 65, his obituary observed that he was well known in town—evidence that he was a character throughout life.

Two Garrisons, Two Cities

On July 25, 1864, Pvt. David P. Stevens and his comrades in the Martin Guards mustered into federal service at Fort Constitution in Portsmouth Harbor. The timing was notable. Only a month earlier and 60 miles north in Portland, Maine, a schooner operated by a crew of Confederate raiders invaded the harbor, but caused no serious damage.

Fortunately for Stevens, about 19, and the other men in the company, the 90-day enlistment was uneventful. Afterwards, he enlisted as a sergeant in the 1st New Hampshire Heavy Artillery, along with many others from the Guards. Ordered to Washington, D.C., the regiment garrisoned a 10-mile stretch of the city’s defenses and performed picket duty. At some point, Stevens fell ill and died of disease in June 1865.

Bivouac of the Dead at Cold Harbor

Sometime during the night following the fighting at Cold Harbor, two Granite State men buried a beloved lieutenant killed earlier in the day. With the grim work done, the exhausted soldiers lay down to snatch some sleep, using the soft mound of earth as a pillow. The deceased officer, 1st Lt. Gorham Pierce Dunn of the 12th New Hampshire Infantry, had been shot through both legs in a charge, and later finished off by a rebel sharpshooter who sent a musket ball through his chest. According to the regimental historian, he had been talking with a wounded comrade and uttered “Oh, dear!” and collapsed in death after the bullet struck.

A diminutive carpenter born in Massachusetts, Dunn began his service in the 12th as a sergeant, and advanced to first lieutenant by February 1864. Four months later, he met his death at Cold Harbor, a month shy of his 29th birthday. He had long believed he would not survive the war, and had a premonition of death shortly before the battle. His sword, sash and a photograph of his wife, Caroline, were sent home to her. A daughter also survived him, but she died in 1867. Caroline married twice more before she passed in 1926.

The historian of the 12th recalled Dunn’s life and service in the regiment’s history. “Though small in stature he was great in his measure of true worth, and memory, even now, repictures his pleasant face and genial smile, and we sigh to think ‘That one so worthy long to live, So quickly passed away.’”

Dunn was also memorialized by a cenotaph in Walnut Grove Cemetery in Danvers, Mass.

Common Grave at Winchester

The Third Battle of Winchester, or Opequon Creek, is remembered for the big success of “Little Phil” Sheridan in clearing Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s Confederate army from the Shenandoah River Valley—a significant victory for the federals.

In the 14th New Hampshire Infantry, a historian remembered the engagement for a single assault: “The charge of the Fourteenth—holding the right of the line—at the battle of the Opequon was a remarkable performance from any standpoint of criticism. Losing one third of its number in thirty minutes, the regiment advanced persistently until all semblance of formation was destroyed; and the scattered remnants retreated only on repeated orders.”

A total of 53 men and officers were killed or mortally wounded, and another 90 injured. The dead included 23-year-old Sgt. Matthew Macurdy of Company H. Because of the fast-moving pace of the fight, Macurdy’s body was left behind with others. He and 28 of his comrades were later recovered and buried on the battlefield in a mass grave. The remains were later disinterred and reburied at the National Cemetery at Winchester, where, in 1868, the Granite State erected an obelisk to honor its fallen sons.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.