By Scott Vezeau and Ronald S. Coddington

The pop and crack of small arms fire shattered the stillness of a northwest Arkansas afternoon in the autumn of 1862.

The gunplay erupted during a running cavalry fight in the Cane Hill Valley, as a column of Union troopers chased Confederates along a three-mile stretch of country road, through ravines, and over hills to a mound at the base of a mountain. Here, the Confederates leapt from their horses and fought briefly, then scrambled through scattered timber up one side towards the top of the peak. Supported by artillery positioned along the crest, they determined to make a stand.

The federals paused, calculating that its cannon would be ineffective in the terrain. The only apparent option: take the mountain by storm.

Two regiments, now dismounted, formed and rushed up the slope with wild shouts, as a perfect storm of shot and shell poured down from the mountaintop. The first regiment in line was the stalwart 2nd Kansas. Behind them marched the Cherokees of the 3rd Indian Home Guard, which included one of the Cherokee Nation’s most respected spiritual and political leaders, Lt. Col. Lewis Downing.

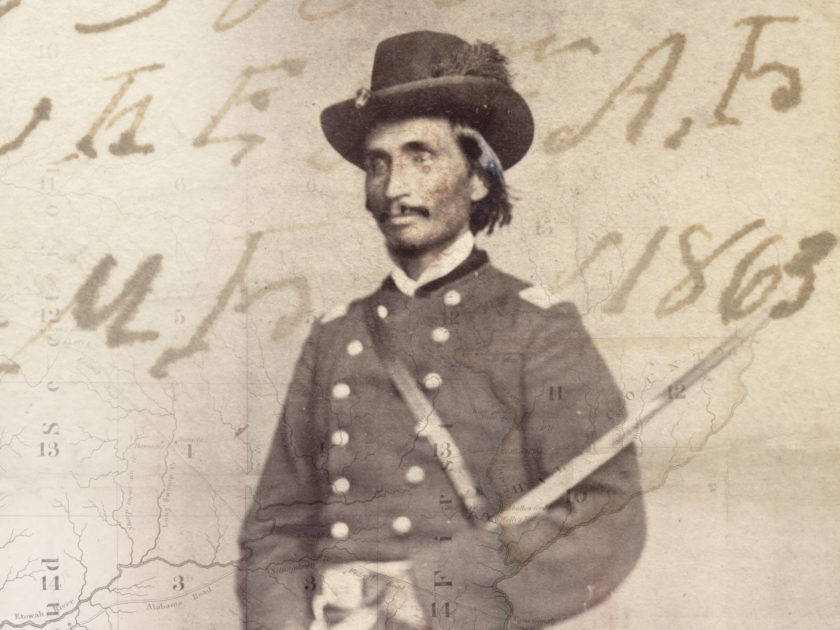

![The inscription on the back of this portrait of Lewis Downing, translated from the original Cherokee alphabet: Lewis Downing / John Manning / Good man / From over the sea [or] Across the creek / A great friend / I will always / Remember him / Here among the chiefs / June 14 1863. Carte de visite by Whitaker & Co. of Philadelphia, Pa. Private Collection.](https://atavist-migration-2.newspackstaging.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/cherokeeb-1511389059-25.jpg)

Just a few months earlier, Downing had donned Confederate gray.

The story of his life and military service represents the struggles of the Cherokee nation he would someday lead.

Born four decades earlier in eastern Tennessee, Downing, or Luyi Tuwanosgi, traced his heritage to full-blooded Cherokee warriors, a British army major and an Irishman. In October 1838, when about 15, Downing walked the infamous Trail of Tears to begin a new life in Indian Territory (present day eastern Oklahoma). He made the trek through the harsh winter climate as part of a group of 1,250 Cherokee brothers and sisters. The leader, Welsh-born Baptist missionary Evan Jones, had originally protested the federal government’s Indian Removal Act that ended in a cruel forced migration. But Jones realized that resistance was futile, and took the initiative to leave on his own accord.

The reverend and his group arrived in Indian Territory in February 1839 with 1,033 remaining souls. Young Downing became a convert of Jones, and within three years had risen to prominence among his fellow villagers in Westville, located in the Goingsnake District of the new Cherokee nation.

Downing’s star rose quickly. By 1844, at age 21, he was an ordained pastor with his own church. The following year he took an elected seat as senator of his district. In politics, Downing was an adherent of John Ross, a mixed-race Cherokee who had fought the British under Gen. Andrew Jackson during the War of 1812. Ross went on to become a staunch defender of Cherokee rights as Principal Chief of the nation.

Downing revealed his spiritual nature in a speech before an 1852 gathering of the Baptist Missionary Union in Pittsburgh, praising the Cherokee translation of the Bible.

“The efforts made before this translation to spread abroad the light of the gospel among them, was something, in my mind, like the dawn of a new day, just before it breaks on the world; but now, since it is disseminated among my nation, it is like the light of the sun when it breaks forth and shines upon the earth.”

Nine years later, the storm clouds of another war obscured that light. In May 1861, Chief Ross issued a proclamation that declared his nation neutral, and urged its warriors to refrain from partisan demonstrations. But unhealed wounds caused by decades of hostile government policy fueled dissension within the ranks of warriors. Two newly minted Confederate brigadiers, Indian Territory commander Ben McCullough and special envoy Albert Pike, pressured Ross to side with them. The generals enjoyed the support of Ross’s longtime rival, Stand Watie, who had been appointed a Confederate colonel after the declaration of Cherokee neutrality.

A mass meeting called by Ross on Aug. 21, 1861, rallied an estimated 4,000 warriors. Bowing to political realities and maneuvering to keep the Cherokee nation unified, Ross recommended they enter into treaty negotiations with the Confederacy. A series of resolutions were passed, including the recognition of slaves as property and the denunciation of abolitionists.

Deep divisions remained however, as illustrated by the formation of two regiments of mounted rifles very dissimilar in character.

The 1st, commanded by Col. John Drew, and with Downing as chaplain, sided with Ross and his pro-Union abolitionist agenda. The regiment organized with an understanding that they would be confined to service within the borders of the Cherokee homeland.

According to one account, Downing founded a paramilitary branch of the Keetoowah Society.

Some of Drew’s men, including Downing, reportedly held membership in the Keetoowah Society, a religious organization founded to preserve traditional Cherokee culture. They preached a gospel of unity, organization and activism. According to one account, Downing founded a paramilitary branch of the Keetoowah. “This association was a secret organization of Union men, formed for the purpose of strengthening the hands of the loyal, and reassuring them by a knowledge of their strength and of their friends. That they might know each other they wore a pin stuck into the lapel of the coat in a peculiar manner, which was, however, discovered by the traitors, and some other sign had to be adopted; but they are still known as ‘Pin Indians.’”

The 2nd, led by Col. Watie, was composed of warriors who embraced Southern ways, including the ownership of about 4,000 slaves.

Drew’s regiment became undone almost as soon as it formed. A late 1861 campaign to subdue anti-Confederate Creeks and Seminoles resulted in desertions by warrior-soldiers that refused to fight fellow Indians. The Confederate defeat at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Ark., in March 1862, further destabilized the regiment, and a federal invasion of Indian Territory prompted the final disbandment of the regiment during the summer. As part of the breakup, Downing led 200 of his men across federal lines on July 6, 1862.

Downing immediately joined the Union’s 3rd Indian Home Guard as lieutenant colonel. The move marked his transition from religious leader to a senior field officer. He reported to the regiment’s colonel and commander, William A. Phillips, a Scotsman who had a successful career as a journalist and lawyer before he joined the army.

One of the earliest engagements by Phillips, Downing and the Indian Home Guardsmen occurred in the Cherokee homeland. On July 28, 1862, they, and other Union forces, routed Confederates at Bayou Barnard. The Union force held its position for three days, during which time it assisted in the evacuation of Chief Ross and the Cherokee archives from the now war-torn country engulfed in its own civil war. Ross fled in exile to the east and formed a pro-Union government, while Col. Watie became Chief of the pro-South Cherokee government.

The dual governments existed through the rest of the war.

Downing remained with his regiment and participated in numerous actions. One was the assault against Confederates making a stand from a mountaintop during the Battle of Cane Hill on Nov. 28, 1862. The Union brigadier in charge, James G. Blunt, recorded in his official report, “The resistance of the rebels was stubborn and determined. The storm of lead and iron hail that came down the side of the mountain, both from their small-arms and artillery, was terrific; yet most of it went over our heads without doing much damage.” The Kansans and Cherokees reached the crest and drove off the rebels.

“We should be one in our laws, one in our institutions, one in feeling and one in destiny.”

Downing could have continued in active field command. He had received praise for his abilities as a soldier. But he was called away to the Indian Territory village of Cowskin Prairie in mid-February 1863 to preside over an historic meeting of the pro-Union Cherokee National Council. Though a government without a country, for Stand Watie and his pro-South faction controlled the homeland, the Council affirmed its ties with the U.S., and passed an act to abolish slavery in its territory. The Cherokee Emancipation Proclamation passed on Feb. 19, 1863; mere weeks after President Abraham Lincoln issued his proclamation.

Cowskin Prairie thrust Downing into senior leadership role on behalf of the Cherokees. He soon left for Washington as a member of a delegation to assist Chief Ross in mending fences with the Lincoln administration over the Confederate alliance a year earlier. They also sought greater protection from the Union army from rebels in Cherokee territory, which could provide its citizens with the freedom to engage in agricultural pursuits. According to one news report, Downing and Chief Ross called on President Lincoln at the White House on June 6, 1863.

Two additional delegates had joined Ross and Downing. Capt. James McDaniel of the 2nd Indian Home Guard traveled with Downing to Washington. The other delegate was Downing’s spiritual guide and mentor, Evan Jones. According to an eyewitness, Indian Affairs Special Agent Addison G. Proctor, Ross explained to Lincoln that the Confederate alliance was a “temporary surrender or treaty.” Lincoln replied, “‘Chief Ross, we are not disposed to remember the past; let by-gones be by-gones; your people have two regiments in the Union service, which, of necessary, corroborates what you say.’ Continuing his remarks, as a genial smile lit up his countenance, ‘even were we disposed to take advantage, as a great nation, we would be stopped by our respect for law and equity, from attempting to profit by what was clearly our own default, as we are solemnly pledged by our treaties to protect you from external enemies.’”

About a week later, on June 14, Downing inscribed this carte de visite portrait to a man named John Manning. His identity, and his relationship to Downing, are not known. The photograph was taken in Philadelphia, where Chief Ross had established a residence.

Downing went on to become Acting Principal Chief. He played a key role in efforts to reunite the divided Cherokee nation after the end of the Civil War. Chief Ross was ill and in decline. Downing represented the Union Cherokees, and Stand Watie the Confederate Cherokees, in failed peace councils held in July and September 1865. Negotiations resumed in Washington between the two factions and government representatives, and ended in the recognition of the Union Cherokees as the legitimate government of the Cherokee nation. The Confederate Cherokees ceased to exist. The treaty was signed on July 19, 1866.

Chief Ross died two weeks later. He was 75.

Downing was automatically elevated to Principal Chief, though his tenure was brief. Three months later, the Congress of the reunified Cherokee nation elected William P. “Will” Ross to be its leader. College-educated and steeped in legislative experience, the late chief was his uncle. He faced an uphill battle to heal fresh wounds opened as the factions fought for control of the restored government.

In an effort to bring the two sides together, Downing called for unity, and opposed policies that discriminated against one side or the other. His position launched a movement and a political party that culminated in a crushing victory over Will Ross in a general election held in August 1867.

In his first State of the Union address, Downing declared, “Our laws should be uniform, the jurisdiction of our Courts should be the same over every part of our Nation and over every individual citizen.” He added, “We should be one in our laws, one in our institutions, one in feeling and one in destiny.”

These words, and Downing’s subsequent actions, guided the Cherokee people through a peaceful reconstruction of the government. Elected to office again in 1871, Downing did not complete his second term. In October 1872, he contracted pneumonia and died two weeks later. He was not quite 50. His third wife, Mary, and five children survived him.

Downing’s pivotal role in the reunification of the Cherokee nation has been largely overshadowed by the memory of John Ross, remembered today as the Moses of his people.

But it may be fairly stated that Downing might be remembered as their second Moses.

Special thanks to Zachary Barnes, Language Technology Assistant of the Cherokee Language Program of the Cherokee Nation.

References: Official Records; Meserve, “Chief Lewis Downing and Chief Charles Thompson (Oochalata), Chronicles of Oklahoma (September 1938); Foreman, Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indians; Baptist Missionary Magazine (October 1842); Pittsburgh Gazette, May 22, 1852; New Orleans Crescent, Sept. 5, 1861; Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture; Minges, “‘Are you Kituwah’s son?’ Cherokee Nationalism and the Civil War,” Union Theological Seminary; Gaines, Confederate Cherokees: John Drew’s Regiment of Mounted Rifles; Detroit Free Press, Jan. 28, 1863; Cleveland Daily Leader, April 4, 1863; “Cherokee Emancipation Proclamation,” Archives Division, Oklahoma Historical Society; Letters Received by the Adjutant General, 1861-1870, National Archives; Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1863-1870, National Archives; Detroit Free Press, June 8, 1863; Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the Year 1863; Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 19, 1865; Public Laws of the United States of America, Passed at the First Session of the Thirty-Ninth Congress, 1865-1866.

Scott Vezeau of Clarksville, Tenn., is a collector and researcher of antique images. He is a graduate of the United States Military Academy (West Point) and a retired U.S. Army Infantry Officer.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.