By Melissa A. Winn

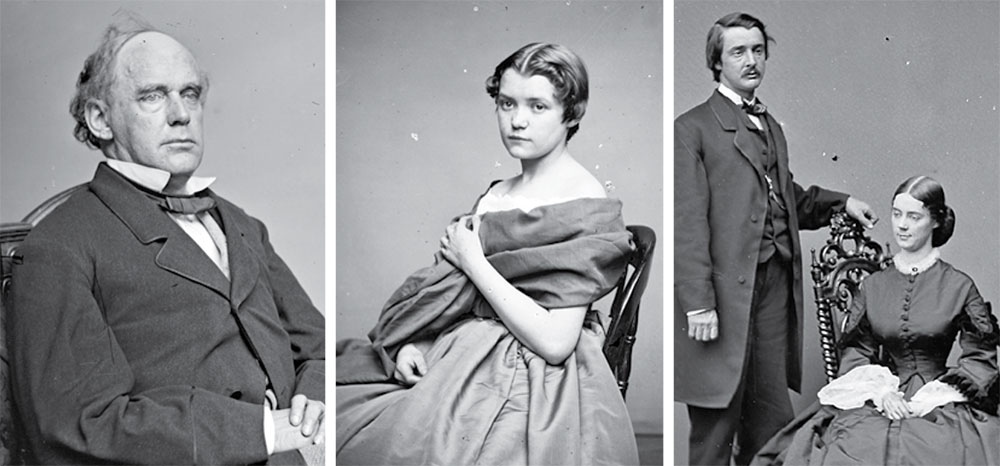

As a woman of the 19th century, Kate Chase owed her privilege and stature to her father Salmon P. Chase’s political positions. However, she made her own popularity and reputation throughout the Civil War years as the reigning social queen of Washington, D.C. She was bright, attractive, vivacious, and most of all ambitious.

Born Katherine Jane Chase on Aug. 13, 1840, in Cincinnati, she was the eldest surviving daughter of Chase and his second wife, Eliza Ann Smith. Her mother died of consumption shortly after Kate’s fifth birthday and her father soon remarried a woman with whom Kate clashed. Sent off to a boarding school in New York at age nine, the girl emerged as a woman polished in society and politics.

When her father became the governor of Ohio in 1856, his third wife had also passed from consumption and Kate served as Chase’s official hostess.

In 1861, when President Abraham Lincoln appointed Chase Secretary of the Treasury, Kate, just 21 years old, moved to Washington, and quickly became the belle of the capital. Her social standing brought her into a notable rivalry with First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln, as Kate sought to be more than just a hostess—she sought influence.

Kate impressed her father’s friends and the men of the town tripped over her. The German-born American politician Carl Schurz said, “She had something imperial in the pose of the head, and all her movements possessed an exquisite natural charm. No wonder that she came to be admired as a great beauty and broke many hearts. After the usual commonplaces, the conversation at the breakfast table, in which Miss Kate took a lively and remarkably intelligent part, soon turned itself upon politics.”

British journalist William Howard Russell described “her head tilted slightly upward, a faint, almost disdainful smile upon her face, as if she were a titled English lady posing in a formal garden for Gainsborough or Reynolds.”

Presidential aide John Hay was also an admirer. Hay wrote to a friend in late 1863, “The town is dull. Miss Chase is so busy making her father next President that she is only a little lovelier than all other women. She is to be married on November 12th which disgusts me with life. She is a great woman & with a great future.”

Indeed, on Nov. 12, 1863, Kate married the wealthy Rhode Island senator and former Gov. William Sprague IV in a lavish ceremony that was one of the social events of the Civil War era. Sprague had been the youngest governor in the nation during his years in office from 1860-1863, during which he briefly served as an aide to Col. Ambrose E. Burnside during the First Battle of Bull Run. Sprague’s wedding gift to Kate included an extravagant tiara of pearls and diamonds, underscoring both the social and financial aspects of the union.

Shared ambition drove the marriage, though the couple also bore four children, a son and three daughters. Sprague’s infidelities and drinking threatened their union from the start, as did Kate’s rumored philandering and lavish spending.

Kate’s number one priority was always winning her father the presidency. She played a major role as campaign manager for his presidential aspirations in 1864, when he unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination, and again in 1868 when he ran (this time as a Liberal Republican and Democrat) without success. His final run in 1872 also proved unsuccessful. For a woman of the 19th century, Kate proved herself crafty, powerful, and smart, if not always successful.

In 1873, Salmon Chase passed away. By this time Sprague experienced financial troubles, especially after the Panic of 1873, and Kate and William’s already tenuous marriage fell apart. She began an affair with powerful New York Senator Roscoe Conkling. According to reports, Sprague discovered them at his Rhode Island home, chased Conkling with a shotgun, and threatened to throw Kate out a window. Sprague’s drinking and his own infidelities exacerbated the situation. A messy divorce followed in 1882, and Kate took back her maiden name.

She moved to Edgewood, her father’s estate, with her three daughters, where she lived a relatively obscure and impoverished life. When her only son, Willie, committed suicide at age 25 in 1890, Kate herself began to unravel.

She died in poverty at Edgewood on July 31, 1899, of Bright’s disease, a kidney ailment, at age 58. Her small funeral was nearly unattended, although the Cincinnati Enquirer did cover it. Despite the modest ceremony, the paper paid her a proper tribute, stating: “No Queen has ever reigned under the Stars and Stripes, but this remarkable woman came closer to being Queen than any American woman has.”

Melissa A. Winn has been enchanted with photography since childhood. Her career as a photographer and writer includes numerous publications, among them Civil War Times, America’s Civil War, and American History magazines. She is currently Director of Marketing and Communications for the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Melissa collects Civil War photos and ephemera, with an emphasis on Dead Letter Office images and Gen. John A. Rawlins, chief of staff to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Melissa is a MI Senior Editor. Contact her at melissaannwinn@gmail.com.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.