By Melissa A. Winn

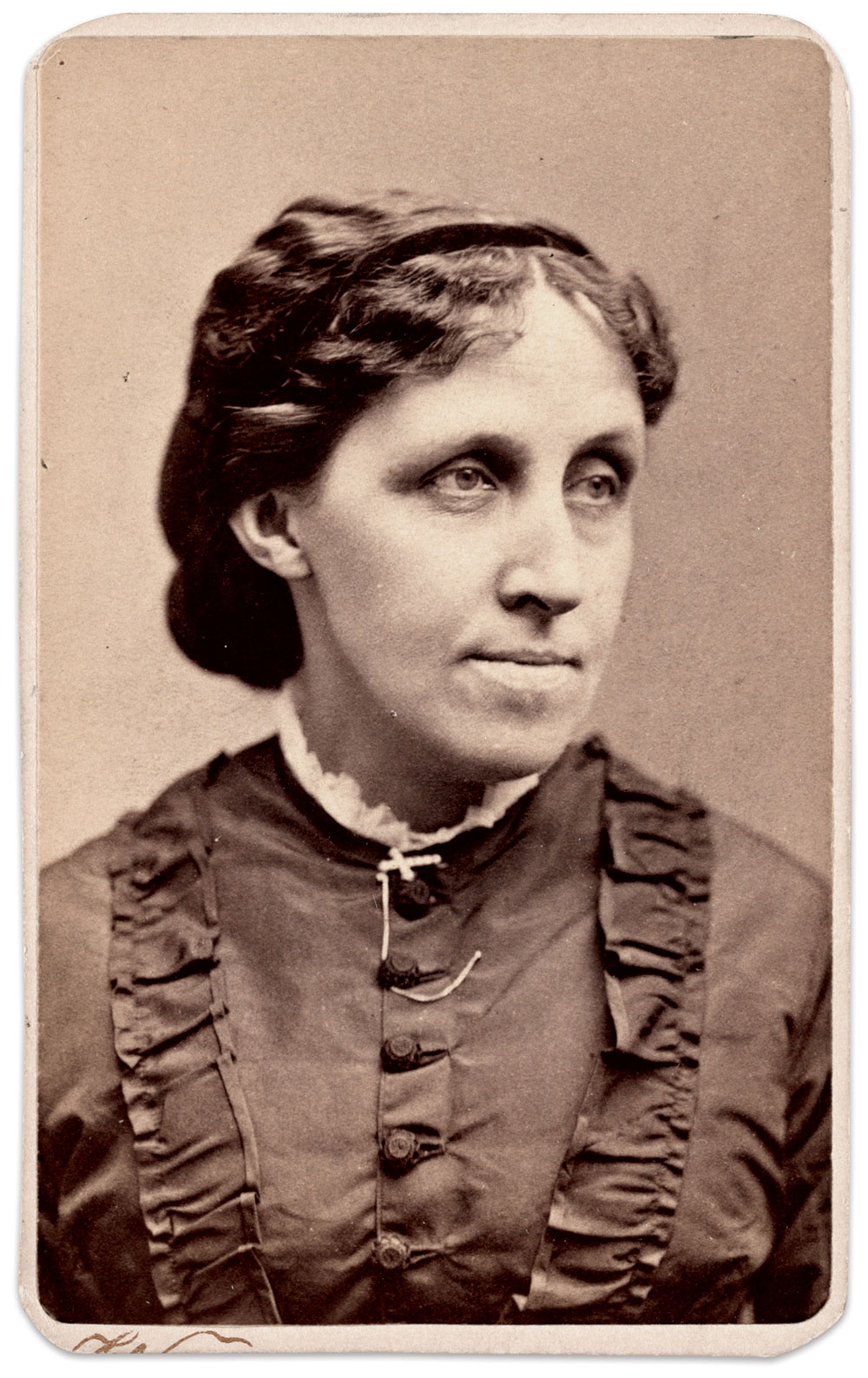

Long before Little Women became a beloved classic, Louisa May Alcott emerged as a young woman of principle and passion, shaped by poverty, reformist ideals, and the brutality of war. Though most remember her as the author who created the storybook lives of the March sisters, Alcott led a life marked by far greater complexity and courage. During the Civil War, she served as a nurse in Union hospitals—an experience that deeply influenced her and helped sharpen her voice as both a writer and a social commentator.

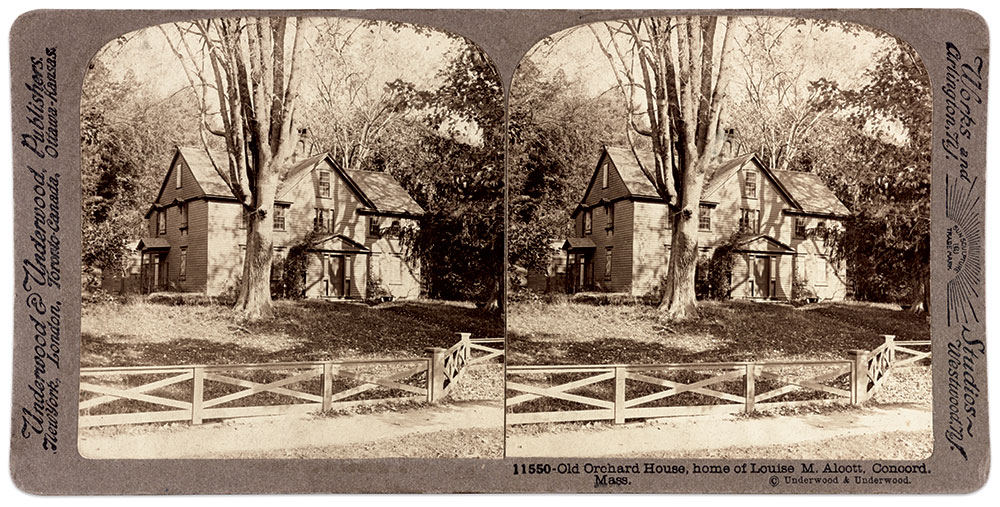

Born November 29, 1832, in Germantown, Pa., Louisa grew up in a household steeped in education, philosophy, and reform. Her father, Bronson Alcott—a transcendentalist thinker and educator—maintained a close association with Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Bronson co-founded a utopian society, where Louisa and her family lived for a brief time. The Alcotts struggled to make ends meet and Louisa and her sisters were often forced to work from an early age, taking on jobs like sewing, teaching, and domestic labor to support the family.

Despite these hardships, Louisa demonstrated fierce independence and deep commitment to causes such as abolitionism, women’s rights—and to writing. A devoted diarist and author, she filled her early works with drama and adventure, often centering around bold female protagonists who defied convention—traits that later came to define her literary career.

Nurse in the Nation’s Capital

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Alcott had already published several works and taught in classrooms, but she longed for more. Like many other women, she felt compelled to support the war effort. If allowed, Louisa would have enlisted as a soldier; denied that path, she pursued service as a nurse instead. “Help needed…and must let out my pent-up energy in some new way,” she wrote in her journal.

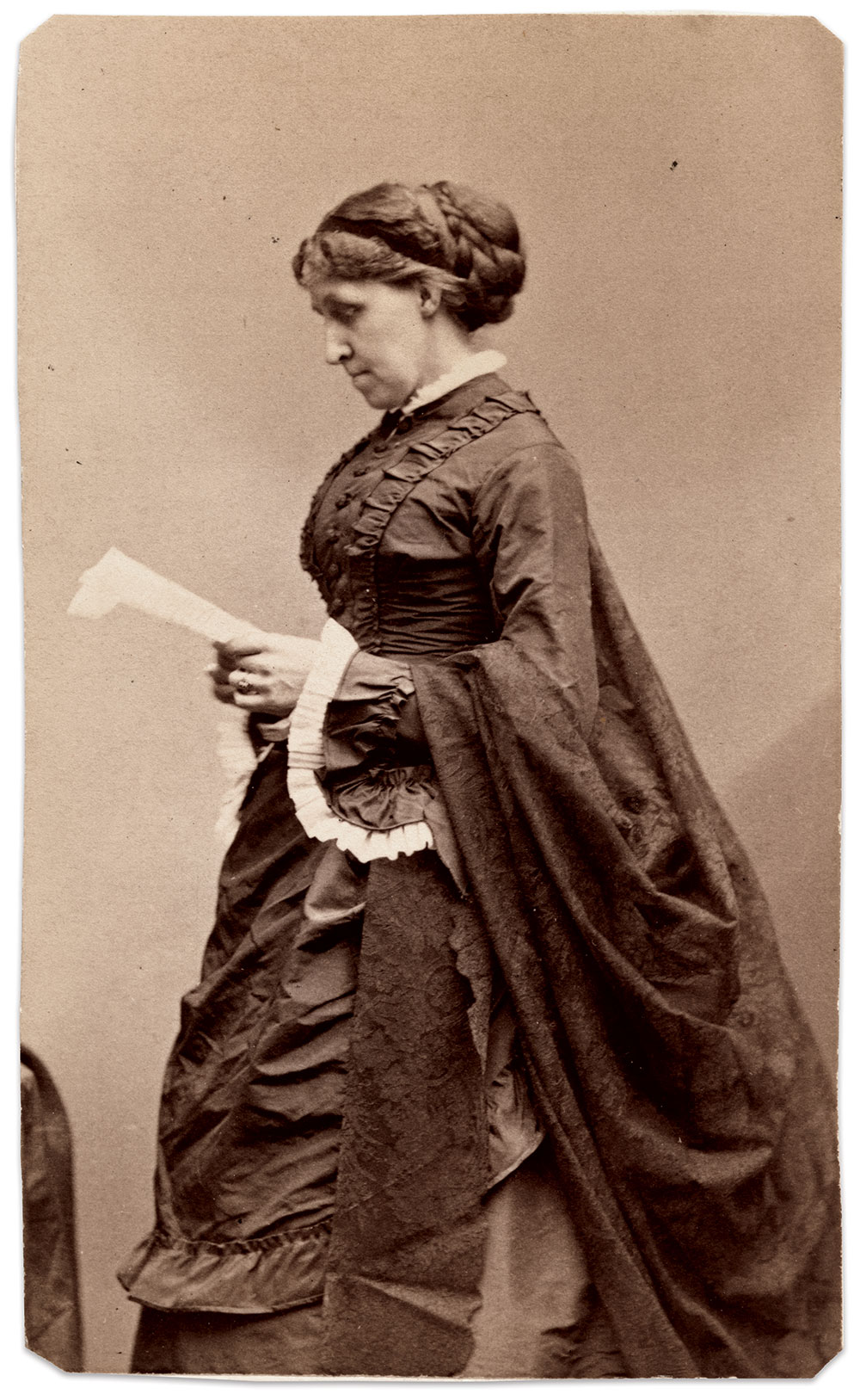

In December 1862, and just 30 years of age, she left her home in Concord, Mass., and traveled to Washington, D.C. “full of hope and sorrow, courage and plans.” Assigned to work at the Union Hotel Hospital in Georgetown, she cared for soldiers wounded at Fredericksburg, one of the war’s bloodiest battles.

Her letters from this period reveal a sobering view of war. Alcott, like other nurses, had no formal medical training. She worked twelve-hour shifts tending to wounds, bathing patients, writing letters for them, and offering comfort as many succumbed to infection or trauma. The war brought no nobility or glory—only bloodshed, cruelty, and exhaustion.

In a letter home, she wrote: “A more perfect pestilence-box than this house I never saw… wounded men, dying men, and decomposing flesh made the air oppressive.”

After just six weeks, Alcott contracted typhoid pneumonia and remained confined to her room, unable to continue her nursing duties. Doctors treated her with calomel, a poisonous mercury compound commonly used during the Civil War. Her condition deteriorated, and she drifted in and out of consciousness, haunted by alarming hallucinations. The hospital doctors, Army Superintendent of Nurses Dorothea Dix, and her fellow nurses all tried to convince her to return home. The hospital matron eventually telegraphed her father, Bronson Alcott, who came to Washington, D.C. and brought her home.

Though her nursing career ended abruptly, it gave Alcott the raw material for one of her earliest successful works: Hospital Sketches. Published in 1863, the book offered a lightly fictionalized account of her time in the hospital and introduced readers to “Tribulation Periwinkle,” Alcott’s narrator and stand-in. The sketches blended humor, realism, and sorrow in a way that captured the public’s imagination and revealed the emotional cost of war—especially through a woman’s perspective.

Critics praised the work for its honesty, clarity, and empathy. Alcott’s vivid descriptions of the wounded, her observations of military doctors, and her reflections on grief and human endurance offered a rare look into the Civil War hospital system.

Alcott continued to write, contributing stories to magazines and producing sensational “blood-and-thunder” tales under pseudonyms to earn money. In 1868, she published Little Women, which drew heavily from her own life, especially her relationships with her sisters and her upbringing in Concord, Mass.

Jo March, the spirited and rebellious heroine of Little Women, clearly took shape from Louisa herself—a tomboyish writer driven by strong ideals and a fierce desire for independence. Though the novel had a lighter tone than her earlier war writing, it still carried themes of resilience, sacrifice, and moral growth.

Little Women achieved immediate success and brought financial stability to Alcott for the first time in her life, but she never abandoned her progressive values. She remained active in the women’s suffrage movement, became the first woman to register to vote in Concord, and continued writing stories that emphasized integrity, charity, and justice.

Alcott died in 1888 at the age of 55 from a stroke, that some believe resulted from lingering complications related to mercury poisoning from her treatment during the Civil War.

In Hospital Sketches, she wrote: “Pain and death are not the greatest evils in the world… It is not easy to comfort suffering, soothe pain, or close the eyes of the dead, but these are things that must be done.”

Louisa May Alcott did them all—and turned them into art.

Melissa A. Winn has been enchanted with photography since childhood. Her career as a photographer and writer includes numerous publications, among them Civil War Times, America’s Civil War, and American History magazines. She is currently Director of Marketing and Communications for the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. Melissa collects Civil War photos and ephemera, with an emphasis on Dead Letter Office images and Gen. John A. Rawlins, chief of staff to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Melissa is a MI Senior Editor. Contact her at melissaannwinn@gmail.com.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on ““I Set Forth in the December Twilight””

Comments are closed.