By Scott Valentine

Many a Northern man did not answer the call to join the Union army in 1861. One of them, Samuel Augustus Duncan, continued teaching students at Dartmouth College, his alma mater. The valedictorian of the Class of 1858 and New Hampshire native, the 25-year-old might have remained on campus.

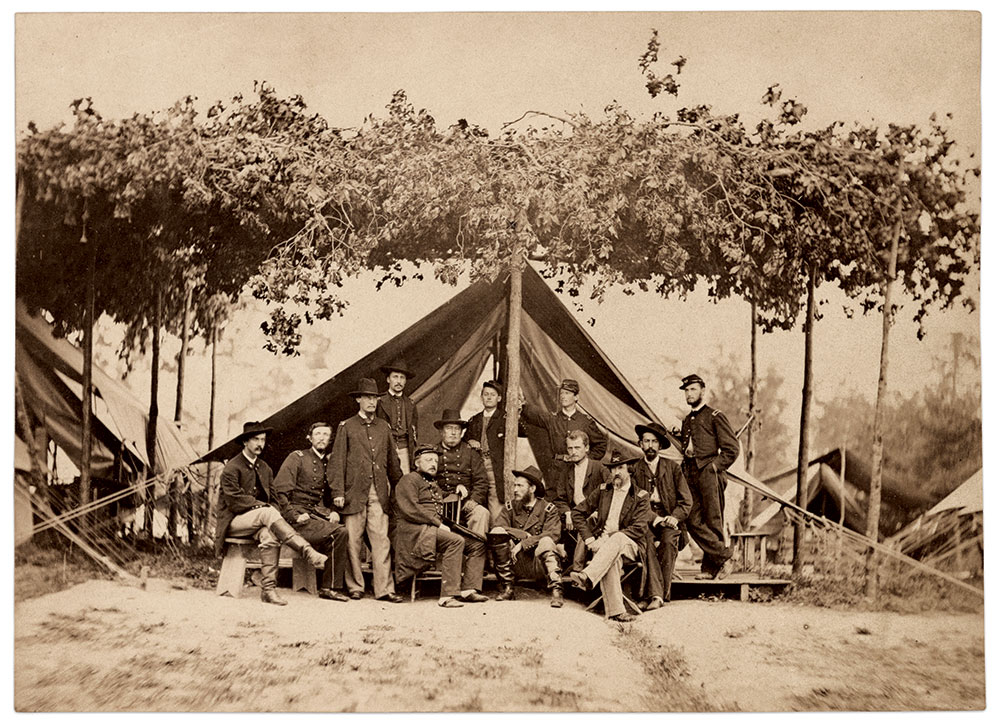

But the failures of the Peninsula Campaign prompted him to act. In late 1862, he began his service as major of the Granite State’s 14th Infantry. Deployed to Washington, D.C., Duncan grew frustrated by the lack of activity and sought higher command in the newly forming U.S. Colored Infantry (USCT) regiments. Approved by the Examining Board, he received a colonel’s commission in the 4th USCT in late 1863.

A little more than a year later, Duncan—now commanding a brigade composed of the 4th and 6th USCT in Brig. Gen. Charles Paine’s division of the 18th Corps—received orders from Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler to lead an assault on the Confederate defenses at New Market Heights during the Siege of Petersburg.

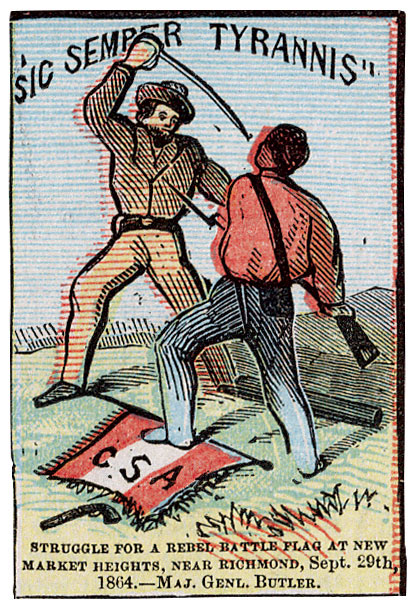

Duncan and his brigade faced a brutal gauntlet: swampy ground, a brook, thick brush, and a line of sharpened wooden stakes. Leading the 4th on foot, Duncan advanced directly into the heat of the enemy’s fire. Sergeant Maj. Christian Fleetwood of the 4th described the moment: “It was sheer madness, and those of us who were able had to get out the best we could. Reaching the line of our reserves and no commissioned officers being in sight, I rallied the survivors around the flag.” Fleetwood received the Medal of Honor for his actions.

A lieutenant in the 6th captured the horror of the charge: “With shouts and cries… we plunge on and on, men dropping… the bullets sing… Surging up to the parapet, our men leap the low, newly made lines and black and white meet, hand to hand, no longer as master and slave.”

The brigade was shattered. Few reached the Confederate trenches. Of the 700 men who took part, more than 400 were killed, wounded, or missing. Duncan had his hat shot off and his uniform pierced by two bullets before being seriously wounded in the ankle and forced to leave the field. He spent five months recovering.

In an after-action report, Maj. Gen. Butler stated, “Better men were never better led—better officers never led better men. With hardly an exception, officers of colored troops have justified the care with which they have been selected. A few more such gallant charges, and to command colored troops will be the post of honor in the American armies.” In the same report, Duncan was breveted brigadier general for gallantry and a subsequent major general of volunteers brevet.

Duncan became a patent lawyer after the war. He died in 1895 at age of 69.

Scott Valentine is a MI Contributing Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on ““Better Men Were Never Better Led””

Comments are closed.