By Melissa A. Winn

Few people did so much for so many Wisconsin Civil War soldiers as Cordelia Harvey. In her brief time as the state’s first lady, she played an important role as a caregiver. But her major contributions, most notably for the wounded and ill, came after the sudden death of her beloved husband forced her to face a new role and a new future.

Her husband, Louis, was sworn in as Wisconsin’s seventh governor in January 1862. He and Cordelia wasted no time in turning their attention to the care of the state’s soldiers and their families sacrificing for the Union cause. Cordelia served with the Ladies’ Aid Society, while Louis met with soldiers and organized supplies for the men in the field. Following reports of heavy casualties in the 14th, 16th, and 18th Wisconsin infantries at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862, Louis organized what he called a “mission of mercy.” Wisconsin citizens donated more than 90 boxes of supplies, which the governor and volunteer surgeons he had recruited delivered to hospitals near the battlefields.

“Yesterday was the day of my life. Thank God for the impulse that brought me here. I am well, and have done more good by coming, than I can well tell you,” Louis wrote in a letter home to Cordelia on April 17.

Two days later, while boarding a steamboat in a hard rain during the darkness of night, Louis lost his balance and fell overboard. The Tennessee river currents swept him away. His body was recovered about 10 days later, nearly 60 miles downstream, and shipped back to Madison, Wis., for burial. He was only 42 years old.

Though Cordelia had been Wisconsin’s first lady for only 94 days, she would honor and serve its citizens for much longer.

The new governor, Edward Salomon, named Cordelia Wisconsin’s Sanitary Commission agent in September 1862. In this role, she visited sick and wounded soldiers in hospitals along the Mississippi River to ensure they were receiving proper treatment and care. While some hospitals were well staffed with doctors and an adequate number of nurses who Cordelia admired and claimed “had their whole heart in the work,” some hospitals were dirty, overcrowded, and barely staffed with one doctor.

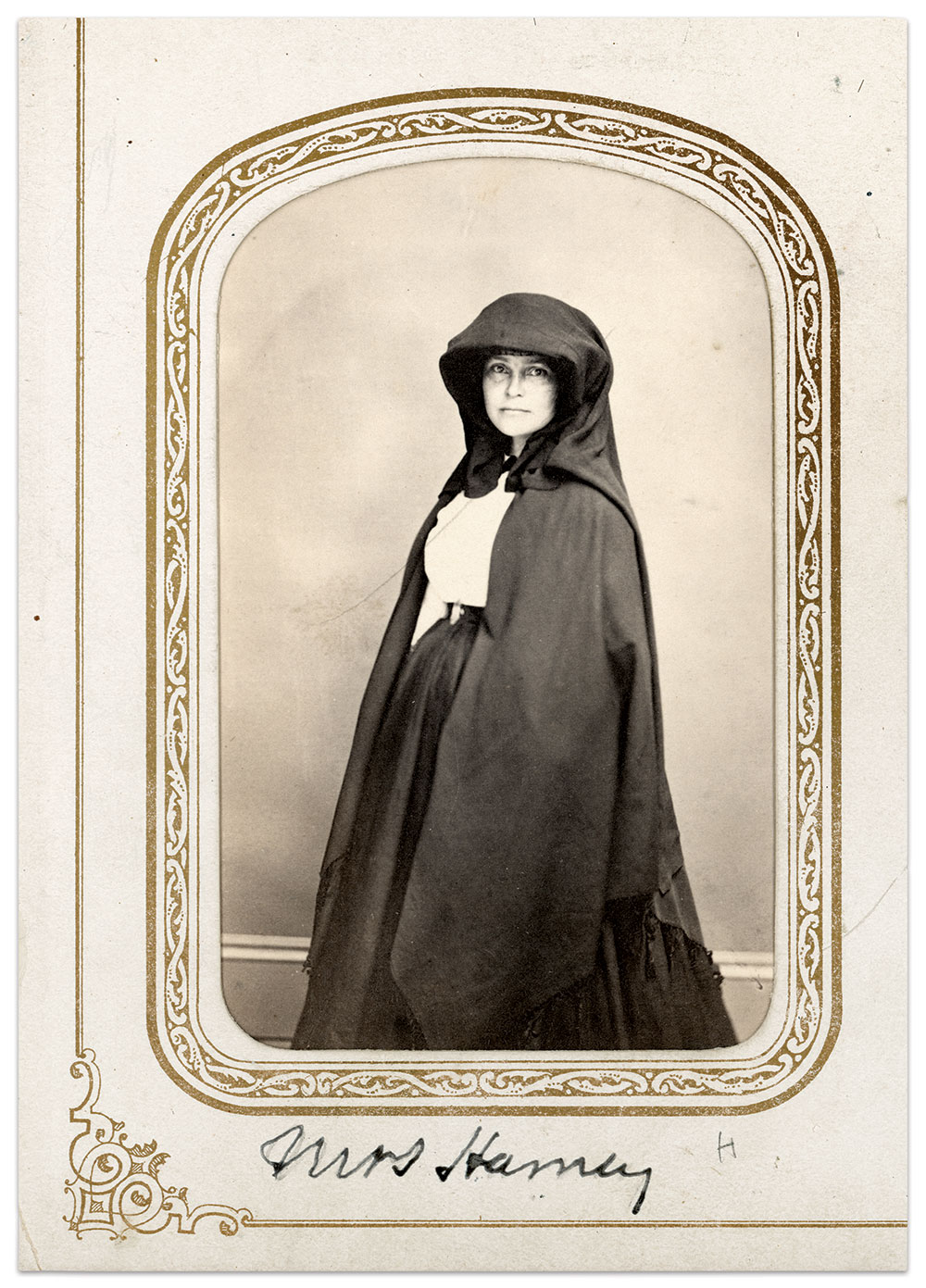

Cordelia sent requests to Gov. Salomon for more supplies, doctors, and nurses. In letters published in state newspapers, she implored Wisconsin women to send food, clothing, blankets, towels, and medical supplies. Well-liked and often wearing her signature black-hooded cape, she visited dozens of hospitals over the next months and became a favorite visitor for many wounded and ill soldiers, who dubbed her “The Wisconsin Angel.”

“I do not wish to be ‘Florence Nightingaled’ nor anything of the kind. I am simply doing my duty and doing very little compared with the great amount there is to be done.”

Granted permission by Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, Cordelia then visited all of the hospitals under his command. One Memphis, Tenn., hospital housed nearly 1,500 soldiers. When the medical inspector vowed to send home any soldier Cordelia listed as unfit to serve again, she spent three days visiting every single one and listing all of those she felt should be sent home. The medical inspector agreed and sent hundreds home.

When soldiers and colleagues began to consider her a hero, Cordelia wrote, “I do not wish to be ‘Florence Nightingaled’ nor anything of the kind. I am simply doing my duty and doing very little compared with the great amount there is to be done.”

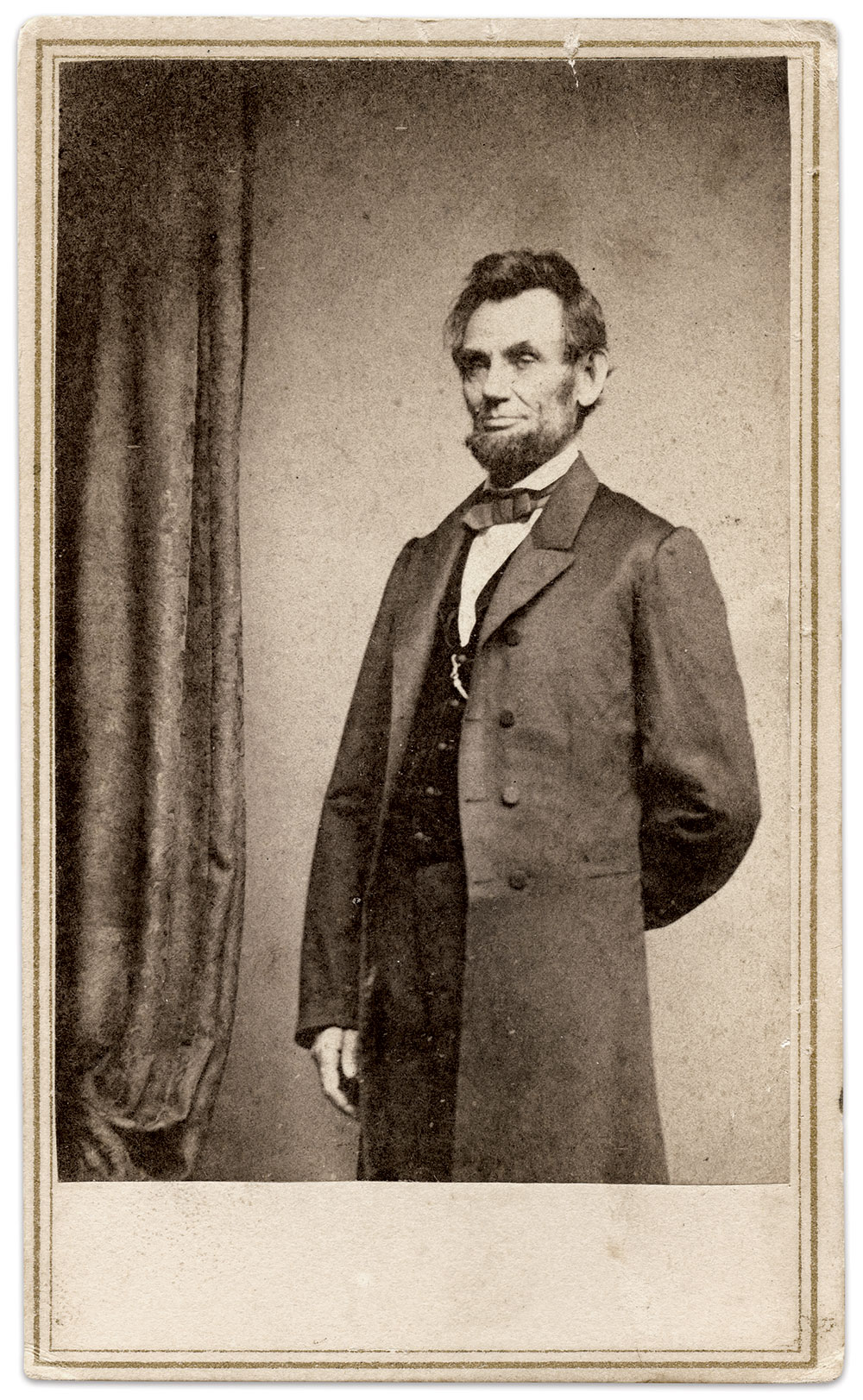

The more time Cordelia spent in Southern hospitals, the more convinced she became that if soldiers could be moved to Northern hospitals with better conditions and cooler air, they could recuperate better and faster. She advocated for military hospitals in Northern states and soon found herself visiting Washington, D.C., to persuade President Abraham Lincoln to establish them. Lincoln feared that men sent home to recuperate would desert, but, after multiple visits, Cordelia convinced him otherwise. Three of these military hospitals were established in Wisconsin, including the Harvey Hospital in Madison.

As the war progressed and Cordelia witnessed more sacrifice by Wisconsin’s men and women, she took up a new cause: the war’s orphaned children.

Cordelia returned home in 1865 with six parentless children and advocated for their care by the state. Meanwhile, she learned the military hospitals she valiantly fought to open would soon be closed for lack of need, and considered them ideal candidates for converting to orphanages.

The Harvey Hospital became the Wisconsin Soldiers’ Orphans Home in January 1866. Cordelia served as its first superintendent. The building housed dormitories, a classroom for 150 students, and an infirmary. The orphanage housed as many as 300 children. As the children were placed in foster care, the numbers dropped and the home was closed in 1875. In the nine years it was open, 683 children between the ages of nine and 14 called it home.

Cordelia married Rev. Albert Chester in 1876, and lived with him in Buffalo, N.Y., until his death in 1892. She then moved back to her and Louis’s home in Wisconsin, where she taught Sunday School. On Feb. 27, 1895, Cordelia died at the age of 70. She was buried next to Louis in Madison’s Forest Hill Cemetery.

Melissa A. Winn has been enchanted with photography since childhood. Her career as a photographer and writer includes numerous publications, among them Civil War Times, America’s Civil War, and American History magazines. She is currently marketing manager for the American Battlefield Trust. Melissa collects Civil War photos and ephemera, with an emphasis on Dead Letter Office images and Gen. John A. Rawlins, chief of staff to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Melissa is a MI Senior Editor. Contact her at melissaannwinn@gmail.com.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.