By Adam Ochs Fleischer

In this installment, we stay in the Wolverine state to study an example used in Jackson by photographer Norman Erastus Allen. Like Kalamazoo, the city of my previous focus, Jackson was an important nexus facilitating commercial activity and transport from Eastern cities to the Western frontier.

Allen, the son of a politically connected merchant, was well suited to have a successful establishment in town, and practiced as a photographer for many years.

Ascertaining the exact location of backdrops and the photographers who used them is often a laborious process involving meticulous research and the triangulation of service records. In this case, however, Allen’s backdrop has been definitively identified by its appearance in cartes de visite, which bear his name and business address on their reverse. In many ways, this provides the gold standard for establishing a backdrop’s location, and the photographer who used it.

Jackson

Founded in 1829 and named after then President Andrew Jackson, residents had considered and ruled out two related names: Jacksonburgh and Jacksonopolis. Though early settlers aspired for the new town to be named the capital of Michigan, Jackson was passed over. The erection of the first state prison in Jackson in 1839 served as a sort of consolation prize. The prison proved a boon for the young town, bringing in jobs and resources from elsewhere in the state.

Jackson steadily grew through the 1840s and 1850s, greatly assisted by the construction of several rail lines, which ran through the town. For a time, Jackson served as the terminus of the Michigan Central Railroad. With its economic prosperity and increasing population, Jackson began to wield political influence.

A seminal event in Jackson history occurred in 1854 when a large anti-slavery event, known as “Under the Oaks,” was held. Due to the heat, the meeting was moved from a local hall to a nearby oak grove. Attendees attacked the institution of slavery vociferously, and agreed in their resolved platform to “cooperate and be known as Republicans.” Many trace the birth of the Republican Party to this very meeting.

By the start of the Civil War, Jackson, now an incorporated town, had established itself as an important regional transshipment station and rail center; a perfect location for the quick transfer of goods and troops. Likely due to this, a military camp was built there in 1863/64. Named “Camp Blair” after Michigan Governor and Jackson resident Austin Blair, the facility became a bustling rendezvous point, convalescent camp and recruitment post. More than 22,000 troops passed through Camp Blair in 1865 on their way home following the war’s conclusion

The Photographer

At the “Under the Oaks” event, on the sweltering hot day of July 6, 1854, Gov. Blair and other prominent locals gave speeches, drew resolutions and endorsed a slate of candidates for public office. Among these new self-proclaimed Republicans was undoubtedly a man named Norman Allen, the photographer’s father. A local merchant and Jackson pioneer, he helped finance the town’s first newspaper and was elected to several local positions. A fervent abolitionist, he is cited as one of the three principal agents who guided escaped slaves along the Underground Railroad through Jackson. As the penultimate stop to freedom in Canada, Jackson played an important role in the network of safe houses.

Following “Under the Oaks,” Allen ran for sheriff with the first crop of endorsed Republicans, but narrowly lost. Fifty years later, he received a glowing mention in a speech commemorating “Under the Oaks.”

While it is unclear whether Allen’s son and namesake adopted his father’s politics, he did inherit his business acumen. In 1857, then 27-year old Norman Erastus Allen started a photographic gallery at the Merchant Exchange Block in Jackson. Perhaps bolstered by the elder Allen’s popularity and the family’s prominence, the endeavor proved a clear success. Allen operated from a series of locations in Jackson through 1864. His younger brother, Charles, a sometime dentist, also operated as a photographer in town. He may have partnered with his older brother. Charles fought in the Civil War with the 26th Michigan Infantry. Though he suffered from disease during much of his service, he survived the war.

While it is unclear whether Allen’s son and namesake adopted his father’s politics, he did inherit his business acumen. In 1857, then 27-year old Norman Erastus Allen started a photographic gallery at the Merchant Exchange Block in Jackson. Perhaps bolstered by the elder Allen’s popularity and the family’s prominence, the endeavor proved a clear success. Allen operated from a series of locations in Jackson through 1864. His younger brother, Charles, a sometime dentist, also operated as a photographer in town. He may have partnered with his older brother. Charles fought in the Civil War with the 26th Michigan Infantry. Though he suffered from disease during much of his service, he survived the war.

While his brother was in fighting in the South, Allen plied his trade, using the patriotic backdrop, which is the focus of this installment. His photographer’s imprint on cartes de visite during the war usually incorporated the official seal of Michigan; clear evidence of the pride he took in his state’s involvement in the war effort. It is unsurprising to learn this, of course, since his father had moved to the wilderness that would later become Jackson, well before Michigan was accepted into the Union. To see Jackson’s and Michigan’s influence and political power fully realized during the Civil War era must have satisfied the Allen clan.

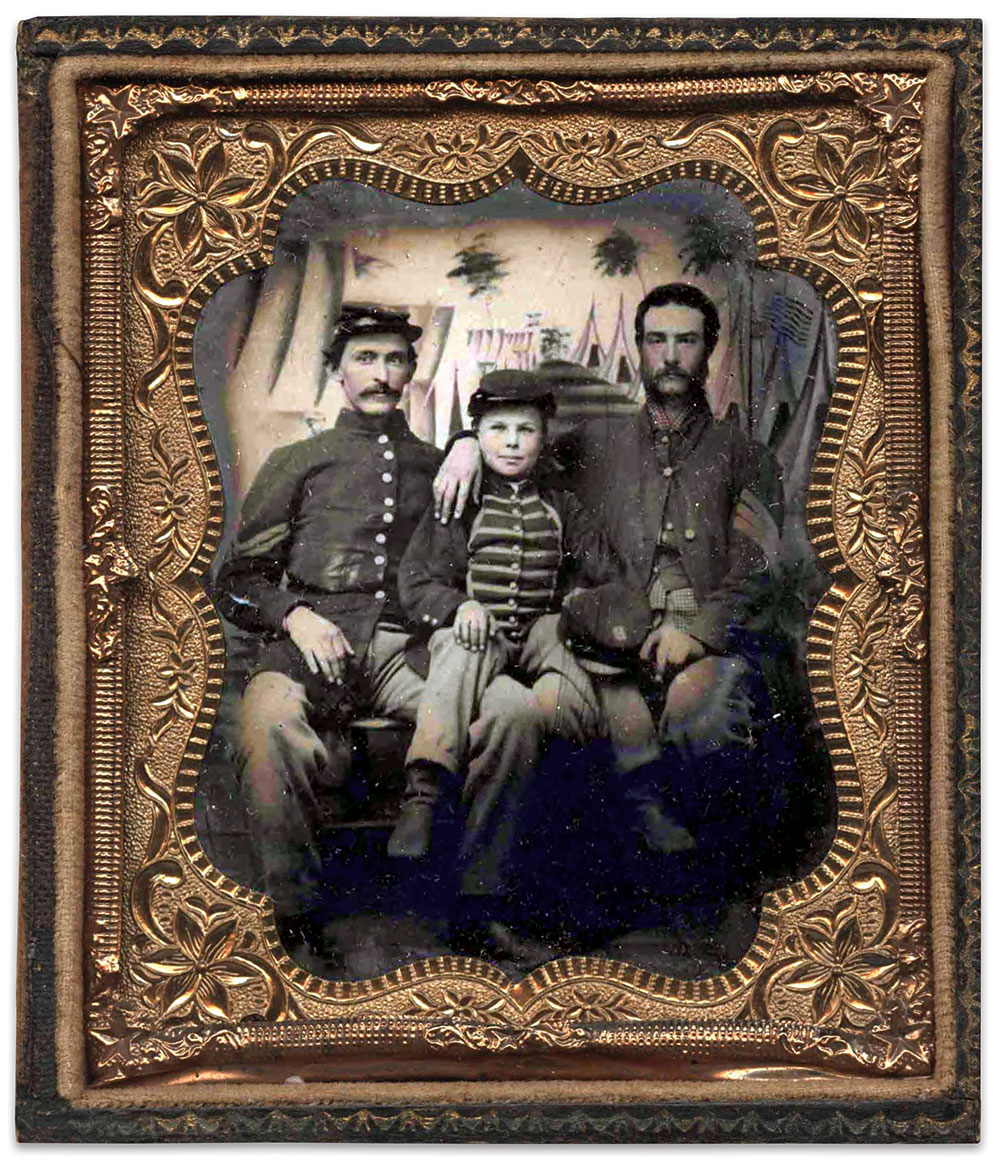

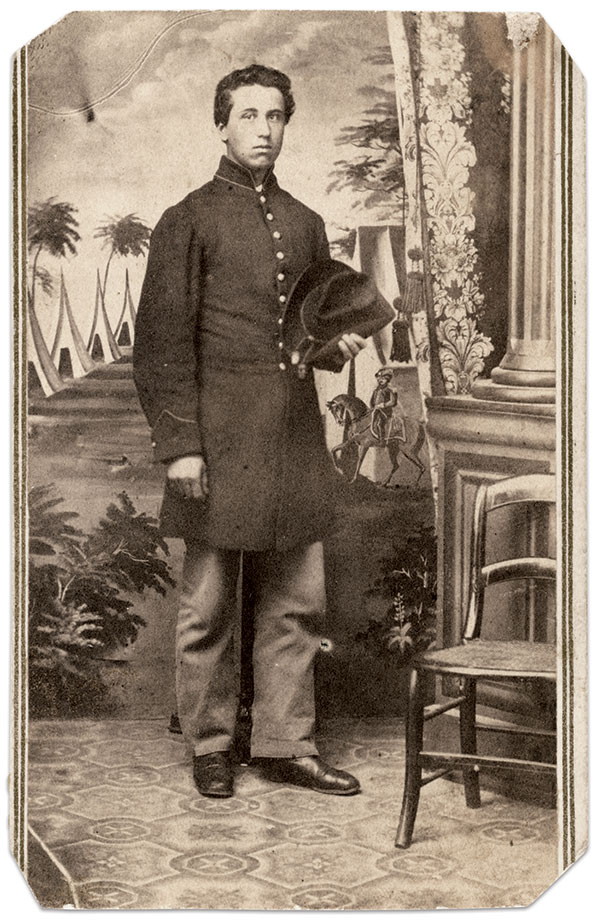

The Backdrop

The backdrop utilizes common motifs we’ve examined in past examples: a Roman column and curtain in the foreground, a cannon and a camp scene resplendent with A-frame tents. In front of the tents is a showy cavalryman riding a horse in motion. Similar figures are often seen in other patriotic backdrops. Where this backdrop somewhat differs is in the flora it depicts. Among the A-frame tents are palm trees, which are not native to Jackson or Michigan. This stirs some interesting questions. Namely, was the artist in the North and seeking to depict the type of area a soldier would likely experience once deployed? Or, was the backdrop rendered in the South and bought by Allen? It is thought provoking to consider, as most patriotic backdrops seem to loosely depict the surrounding landscape of the studio they occupy.

Final thoughts

Allen relocated his studio about 30 miles east to Dexter, Mich., in 1864, for unknown reasons. The move prevented him from photographing thousands of troops making their way through Jackson at the end of the war. Many of these men might have wished to have their portrait taken in uniform for posterity before ending their service, so his decision to leave is a curious one. In any case, it explains the rarity of examples that have survived, which show his backdrop, especially relative to other Michigan backdrops like the Camp Michigan example described previously in Military Images.

I’d like to once again thank collector Dale Nielsen for his assistance in completing this column. Without his keen eye and knowledge of Michigan photography, it would not have been possible to write.

Adam Ochs Fleischer is a passionate researcher of Civil War photography and an admitted image “addict.” He began collecting in high school and quickly became obsessed. He lives in Chicago.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on “The Palm Tree Backdrop of Jackson, Michigan”

Comments are closed.