By Adam Ochs Fleischer

In the previous installment, I focused on a backdrop used in Lexington, Mo., during a storm of sectarian conflict. Identifying the backdrop to photographer Thomas D. Saunders will hopefully prove useful in understanding the context of his images. But because soldiers affiliated with both sides and irregular forces passed through Lexington, the gallery’s location does not necessarily assist in identifying the subjects who sat before it.

The featured backdrop in this column stands in strong contrast. Located in Kalamazoo, Mich., the “Tiger Tree” backdrop likely appears behind soldiers affiliated with a small number of regiments raised or trained in the area. If you spot the distinctive Tiger Tree in an image, you will have an immediate, relatively confined place to begin research.

Kalamazoo

Situated in southwestern Michigan, Kalamazoo was a medium-sized town of about 6,000 in 1860. Equidistant from Detroit and Chicago, Kalamazoo connected the two cities by rail, and, at the start of the Civil War, was considered an important transshipment station. As a nexus of the surrounding area and a conduit to other parts of the country, it became an ideal location to raise regiments for quick training and transportation to the war’s Western or Eastern theaters.

Not long after the onset of hostilities, at least five separate offices were set up in Kalamazoo to enlist men. Through the course of the war, the following units are known to have recruited in Kalamazoo: 2nd Michigan Infantry, 6th Michigan Infantry (later, Artillery), 16th U.S. Infantry, 1st Michigan Cavalry, 11th Michigan Cavalry, 13th Michigan Infantry, 17th Michigan Infantry, 18th U.S. Infantry, 25th Michigan Infantry, 28th Michigan Infantry, 1st Michigan Light Artillery (14th Battery, Battery G), and the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters.

A subset of these regiments also organized in Kalamazoo: the 6th Michigan Infantry, 11th Michigan Cavalry, 13th Michigan Infantry, 25th Michigan Infantry, 28th Michigan Infantry, 1st Michigan Light Artillery (14th Battery, Battery G), and the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters. It stands to reason that the soldiers in these regiments had a lengthy presence in the city, and were more likely to have their photo taken there.

Camp Chandler

If one heard of Kalamazoo before its industrial growth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it would likely have been due to the town’s reputation as a mecca for harness horse racing and other equine events. The Kalamazoo Horse Association, near the southeastern outskirts of the city, constructed a massive track for racing and exhibitions in 1858. Called the National Driving Park, it hosted races and events that drew large crowds and national attention before shuttering in the late 1880s. Its grandest moment occurred not long after its completion in 1859, when the mare Flora Temple (the “Bob Tail Nag” referred to in the famous song Camptown Races) set a one-mile race world record of two minutes, nineteen and three-quarters seconds. Newspapers across the country declared the feat a triumph. The Detroit Free Press reported that after the race there were an exuberant ‘three cheers for Flora Temple, three cheers for Mr. McMann (the jockey), [and] three cheers for the Kalamazoo Horse Association.”

In 1862, with the echoes of the cheering crowd for Flora Temple reverberating across the track, the state expropriated the National Driving Park as a training ground for regiments organized in Kalamazoo. Named Camp Chandler, Lt. Benjamin F. Travis of the 25th Michigan recalled it fondly in his regimental history, writing, “The camping ground in National Park was as fine a place as could be selected for the organization of a military force. It consisted of about 80 acres, with a broad one mile racing track. The camp was fully a mile from the center of the town, and was on its southeastern outskirts. The 6th and 13th regiments had been previously organized there, and the horse stables for the use of exhibitors had been enclosed and provided with bunks, to be used as sleeping apartments and habitation for the soldiers. So we had no tent service while in camp there. Other buildings on the ground supplied the officers and men with headquarter arrangements, storage for supplies, [a] dining hall, and other conveniences.”

Lt. Travis added, “Another feature of preparation for the service was the besieging of the camp with Hawkers, Peddlers and quacks, preaching into the soldiers the need of providing against disease and discomforts of the service, in order to sell and round out a profit on conveniences and medicines as preventative of disease and accident—just as if the government had not been informed sufficiently and made the necessary provision for every emergency.”

One peculiar event recounted by soldiers present at Camp Chandler was an orchestrated “hunt” of buffalo brought by traveling showmen to the grounds in late September 1862. Charging 25 cents for admittance (soldiers were allowed to watch for free), a “hunter” roused the tired herd and “in imitation of the Indian,” as Lt. Travis recounted, repeatedly thrust his spear into one “poor beast” until it sustained a large loss of blood. The buffalo continued to thrash and move about until the “hunter” fired three pistol shots to its head.

Private John A. Wilterdink, 22, of the 25th Michigan wrote to his family, stating that the showmen “brutally killed one [buffalo], in a way too cruel to describe.”

Lieutenant Travis was equally appalled. “It was doubtful which was the greatest brute, the one by nature or the one who would cast aside human and taken up that of the animal.”

Ten days hence, Lt. Travis, Pvt. Wilterdink and the rest of the 25th Michigan left Camp Chandler and headed to war.

Where was the studio?

The “Tiger Tree” backdrop photographer might have been a local, or an itinerant who set up in concentrated areas of military activity to take advantage of the ample market for picture taking. In either case, their identity has yet to be discovered.

While I initially believed the photographer was operating in Camp Chandler, primary evidence suggests they were in Kalamazoo proper, not in the confines of the former racetrack.

Private Wilterdink makes this clear in a letter from Camp Chandler to his family on Sept. 9, 1862: “We are not able to go to town much. Three men per day out of the seventy men in Company “I” is not many. I hope to get a turn soon so I can have my portrait made.”

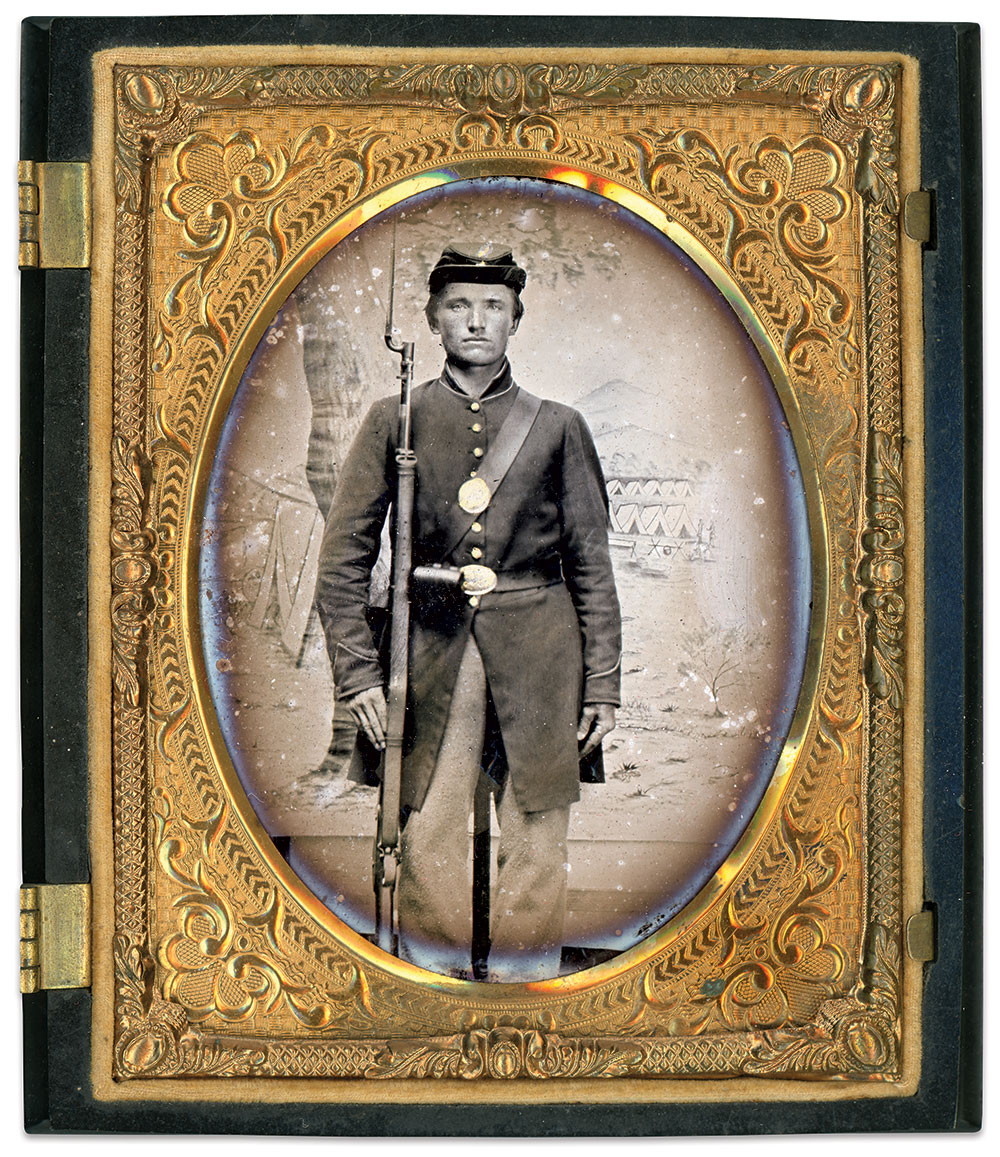

Wilterdink writes later of finally being able to go to town on September 20 (he is actually able to go to town twice in the same week) and makes arrangements to send photos back home, telling his family on September 29, “I had two portraits taken and am sending them along with Rev. Pieters to Ryk Takken. Now you can choose from three…the square one cost 2 dollars and the oval costs 1 dollar and 25 cents. That one you can hang on a wall.”

The image of Pvt. Wilterdink shown here is recorded as being taken on September 20, the day of his first trip to town.

The Backdrop

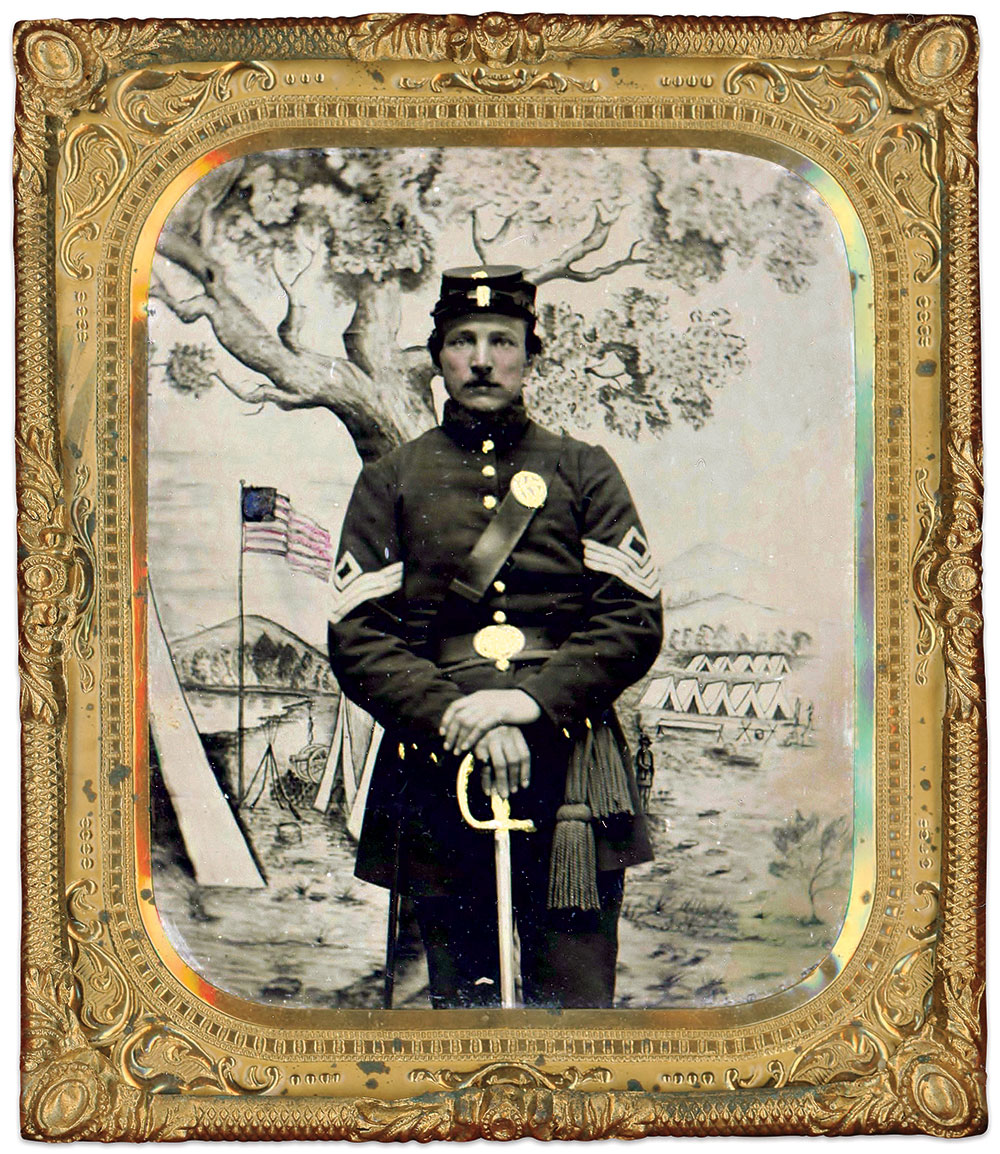

The backdrop depicts a patriotic scene filled with imagery common to this genre. Soldiers appear milling about or on sentry duty. A cannon, an assortment of A-frame tents, a tinted U.S. flag, and other items are visible. What distinguishes this example and gives it its name is the large tree in the foreground of the painting. While the top of the tree is not always visible in portraits, branches thick with leaves extend across the picture plane.

The tree does not appear well rendered in relation to the camp behind it. The striped appearance on the shadowed portion of its left side (from the viewer’s perspective) is curious. It is unclear what the artist’s intention was, my intuition is that it was an unsuccessful attempt at adding realism to the trunk’s appearance.

Special thanks: I owe a debt of gratitude to collector Dale Nielsen, who is responsible for naming the “Tiger Tree backdrop of Kalamazoo” and determining the area of its location. Dale went to great lengths to assist in the research necessary for this article, and without him it would not have been possible to write. Thank you, Dale!

Adam Ochs Fleischer is passionate researcher of Civil War photography and an admitted image “addict.” He began collecting in high school and quickly became obsessed. He lives in Chicago.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.