By Charles T. Joyce

The destructive force of explosive artillery shells and soft lead Minié balls, combined with 19th century military medicine, took a toll on Union soldiers. The wounded included some 25,000 men who sacrificed an arm in battle.

The relationship between these “empty sleeves” and the Northern civilian population was complex. Amputees’ experiences following the end of their active service ranged considerably. Some were able to make the most of their emblems of honor and find a measure of postwar peace and even prosperity. Others struggled and succumbed in the face of a public that became increasingly indifferent to their plight, anxious to move on from the past in the name of national reconciliation.

The men who paid this particular price at the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg fared no differently, as revealed by these representative tales.

July 1: The plains north of town

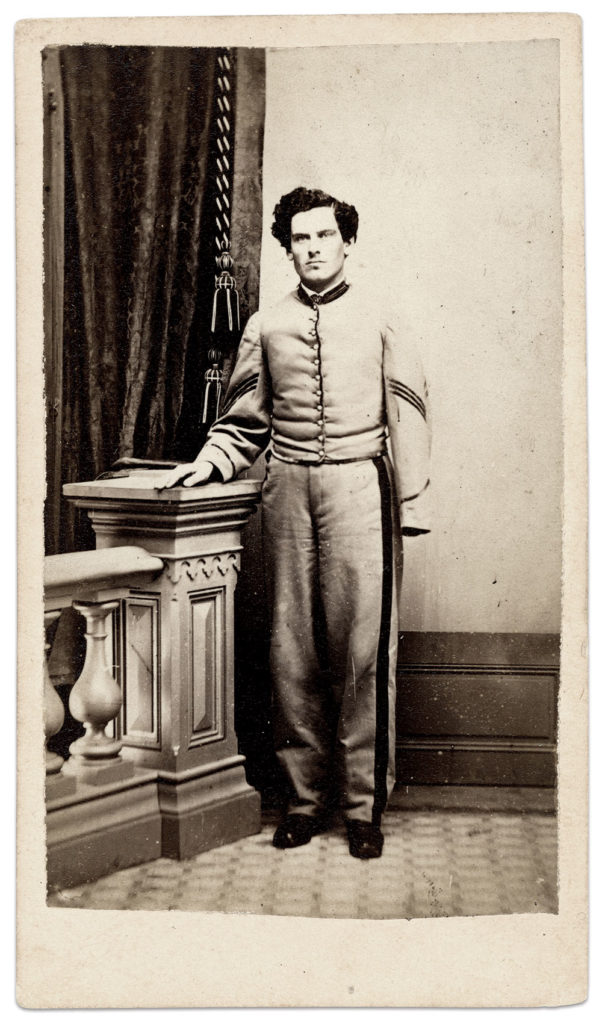

Sgt. Vincent Parsons Carroll

Company E, 25th Ohio Infantry

In July 1861, Ohio farmer Vincent Carroll, 22, enlisted in Company E of his home state’s 25th Infantry. He distinguished himself in uniform and received a promotion to sergeant in his regiment’s color company a month before Gettysburg.

On the afternoon of July 1, 1863, Carroll carried one of the 25th’s battle flags during the brief but frenzied fight near Blocher’s Knoll. At some point a musket ball tore into his left arm. Taken to the 11th Corps field hospital at the George Spangler Farm, medical personnel treated Carroll with cold-water dressings to staunch the flow of blood and facilitate healing. It did not work, and surgeons eventually amputated the bullet-mangled limb.

Following surgery, Carroll served briefly in the Veteran Reserve Corps until discharged at Baltimore in July 1864, exactly one year and one day after his wounding.

Carroll returned to Ohio and drifted aimlessly during the rest of the 1860s, finding it difficult to farm with one arm. In the spring of 1867, he gained admission to the National Home for Disabled Soldiers in Dayton. Released later that summer, administrators readmitted him again in April 1868, before being discharged a final time at his own request that November.

His life took a turn for the better in the following decade. He met and married 18-year-old Harriet Isabel Fickle in March 1871, and landed a job as a telegraph operator for the Central Pacific Railroad Company. He remained in this position for the next 40 years. He made his home with “Belle” and their brood of six children in Anderson, Ind. He died there in 1911, and Belle followed him six years later.

July 2: Action near The Wheatfield

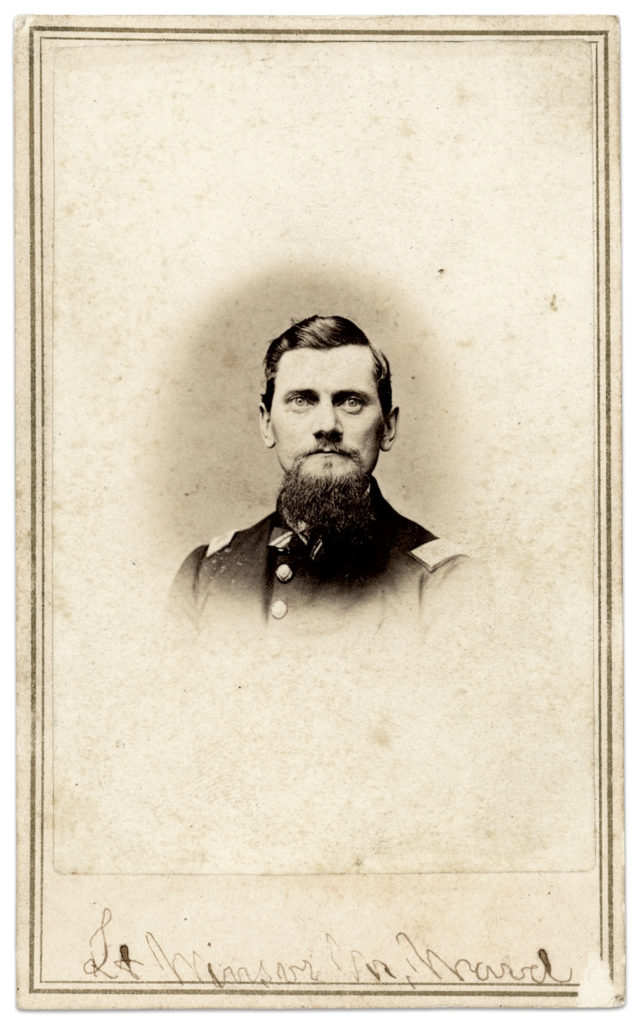

1st Sgt. Windsor Morse Ward

2nd Company, Massachusetts Sharpshooters

By the late afternoon of July 2, Windsor Ward, 29, and his company of sharpshooters, attached to the 22nd Massachusetts Infantry, occupied a position atop Rocky Hill. The tree-covered knoll owned by farmer John Rose overlooked his soon to be famous Wheatfield.

In the subsequent action against Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw’s South Carolina Brigade, Ward suffered a bullet wound to his right arm above the elbow. Ward described the gunshot as “shattering the main bone” of his limb.

Evacuated to a military hospital in York, Pa., Ward had a 3 to 4-inch section of the shattered bone removed in August. This surgery may have been an early orthopedic attempt at “limb salvage” to avoid full amputation, a procedure that today engenders strong debate among civilian and military surgeons. Whatever the motivation, the result for Ward was a withered and useless remnant. The physical limitations and mental challenges he faced equaled those encountered by amputees. Depending upon the result of the surgery and condition of remaining bone, muscle and tissue, he may have looked similar to armless veterans.

Ward learned to write with his left hand and tried, unsuccessfully, to return to duty with his regiment. The army transferred him to the Ambulance Corps. Determined to serve in a larger capacity, he applied for an officer’s commission in the Veteran Reserve Corps. He did so on the strength of what he described as a verbal order from the commander of the 22nd promoting him to the rank of second lieutenant. He appeared before the examining board, which rated his general education as “bad,” and his knowledge of regulations, articles of war and the service “indifferent.”

Ward returned to Massachusetts. Unable to resume the trade of carpenter that he practiced before the war, he applied for and received an invalid pension.

Meanwhile, the federal government offered free artificial arms to veterans in need. Many found them ill fitting, cumbersome and uncomfortable. By one estimate, less than 20 percent took advantage of this benefit. Ward qualified to receive a resection apparatus for his withered limb. He chose instead to seek the monetary value of the device and it is unclear whether this tactic was successful. He struggled financially until 1869, when President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him Postmaster of Peabody, Mass. He held this position into the 1880s. He also served as the Commander of G.A.R. Post 50, strewing flowers upon the graves of comrades every Decoration Day. After a long and painful bout of pancreatitis, Ward died in 1908 at about age 74.

July 2: Somewhere west of Cemetery Ridge, the Union counterattack against Barksdale’s Charge

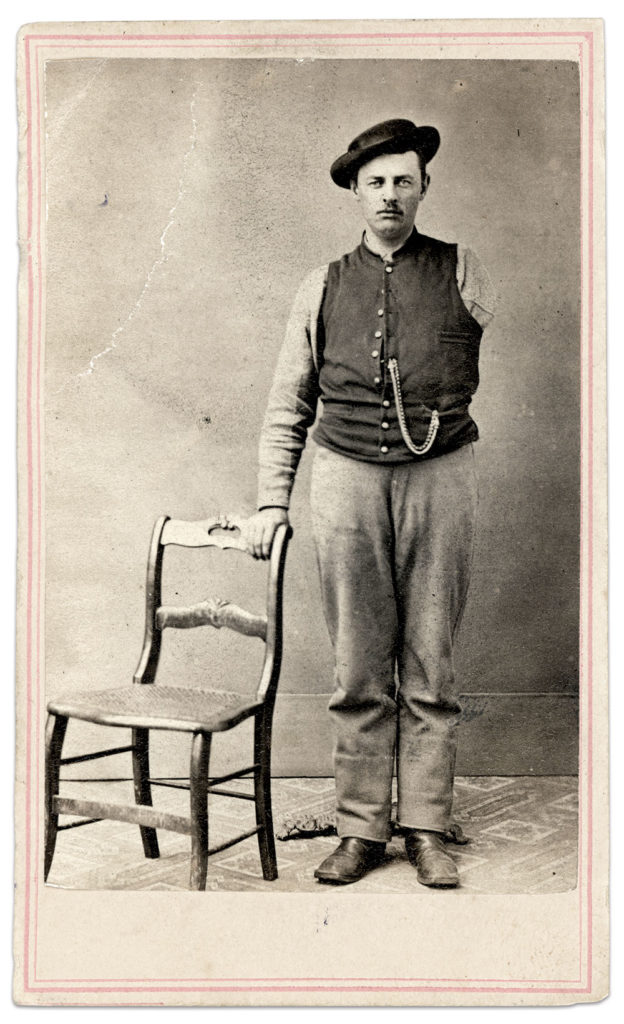

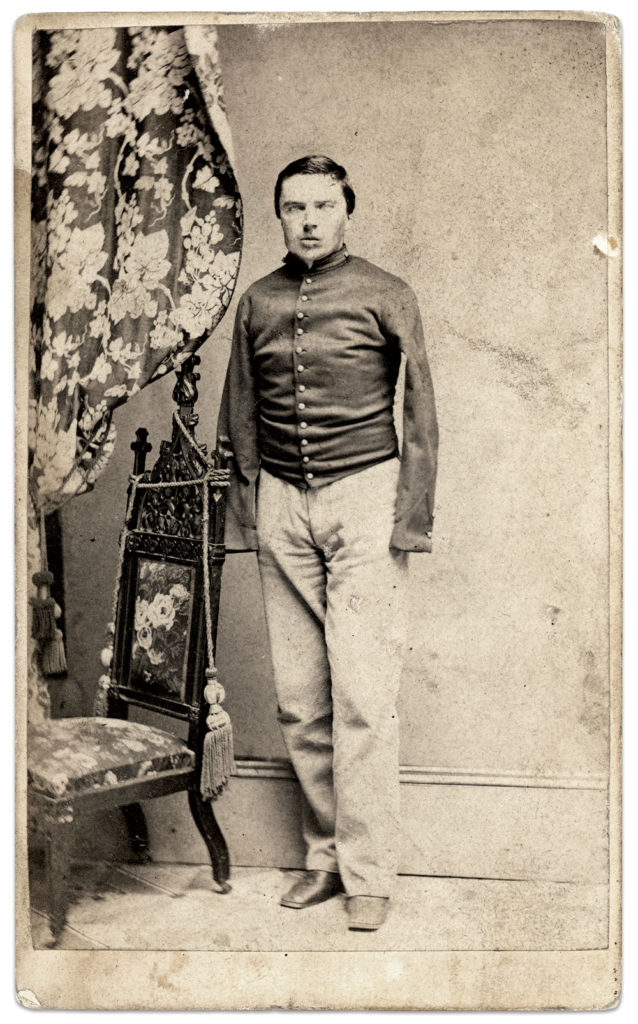

Pvt. Edmund F. Craft

Company F, 126th New York Infantry

Edmund Craft and his comrades in the 126th New York Infantry arrived at Gettysburg seeking redemption. Placed in an untenable position at Harpers Ferry the year before, Confederates forced the surrender of the 126th and its brother regiments in the New York Brigade. The New Yorkers languished on parole at Camp Douglas in Chicago, where they were unfairly labeled the “Harpers Ferry Cowards.” In early 1863, they returned to active duty.

A few months later at Gettysburg, at a supremely crucial point late in the battle’s second day, the New York Brigade charged into the relentless assault of Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s Mississippians, forced them back, and helped save the center of the Union line. The New Yorkers paid a heavy price for this moment of glory. In Craft’s Company F, 22 of 41 men were killed or wounded. Craft received a ghastly bullet wound to his left arm.

The army transported Craft to Baltimore’s Jarvis Hospital, and then, sometime before July 9, to Lovell General Hospital in Portsmouth Grove, R.I. He numbered among 900 Gettysburg casualties sent to the New England hospital. A local newspaper account described them as “dirty, half starved, completely exhausted and generally in miserable condition, their wounds bandaged crudely with old rags.”

The bullet lodged in Craft’s limb was not extracted until July 14. By this time, infection had set in. On August 12, surgeons amputated his arm, according to one record, at “the middle third.” Throughout the fall, healing eluded him. He endured two more amputations, on December 18 and December 22, the latter taking away the “head, and remaining shaft” of the arm. The final surgery, performed by Contract Surgeon Edmund Seyfforth, was listed as one of 47 cases of “Successful Secondary Amputations at the Shoulder for Shot Injury,” in the Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion.

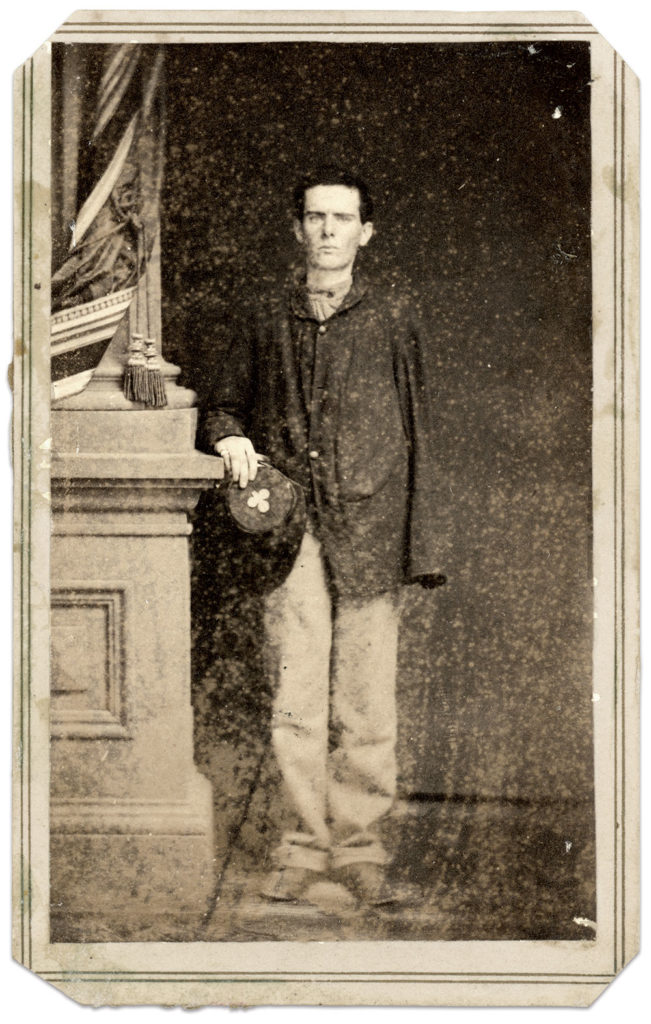

The noteworthiness of Seyfforth’s operation likely prompted this portrait of Craft by photographer Joshua Appleby Williams of Newport, R.I. It was found in an album owned by Miss Annie M. Strout, who served as a nurse at Lovell.

Seyfforth shared more than a common first name with his patient. While performing an operation at Lovell sometime after Craft’s successful amputation, Seyfforth cut his own hand. Blood poisoning necessitated the amputation of several of his fingers and part of his hand. After Seyfforth died in the mid-1870s, his wife struggled to secure a widow’s pension. In 1888, she gained approval from the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Invalid Pensions. But President Grover Cleveland, a nemesis of the pension system, vetoed it on grounds that Seyfforth “had several spells of alcoholism after the war,” and found that the doctor’s troubles were “due to habits of intemperance” and not his injury.

Meanwhile, Craft recuperated and entered the Veteran Reserve Corps on Christmas Day, 1864. After the war ended, he returned to his home in Cayuga County, N.Y., married and fathered two sons in the early 1870s.

He was fated not to live to see them grow up. Death came to Craft in February 1880 at age 39. His tombstone, in a small cemetery in Tyre, N.Y., lies broken and neglected today.

July 2: Stevens’ Knoll, in The Saddle between Cemetery and Culp’s Hills

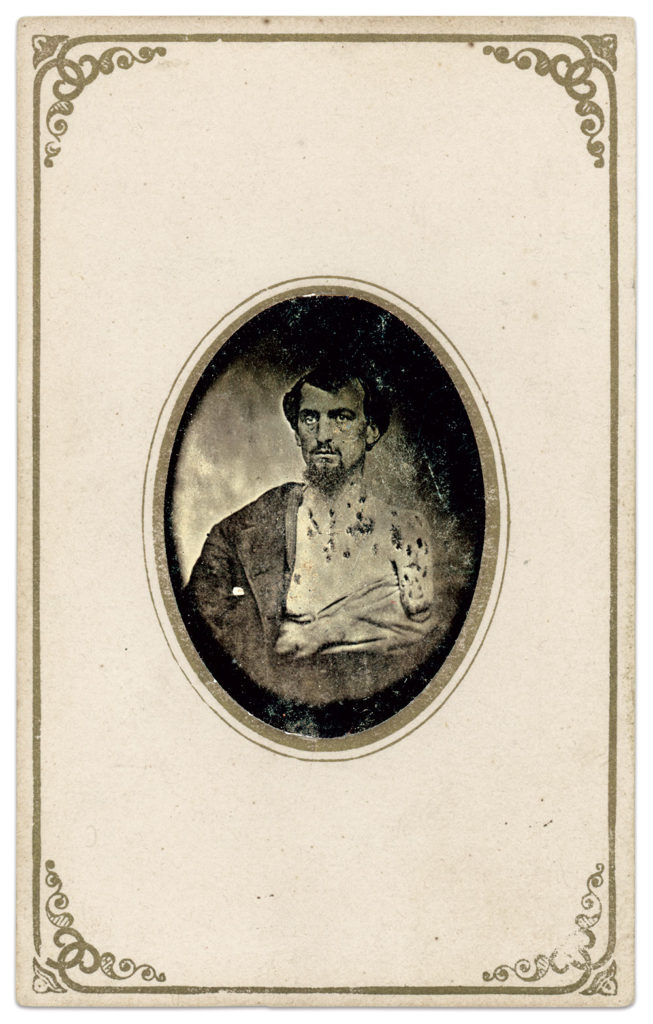

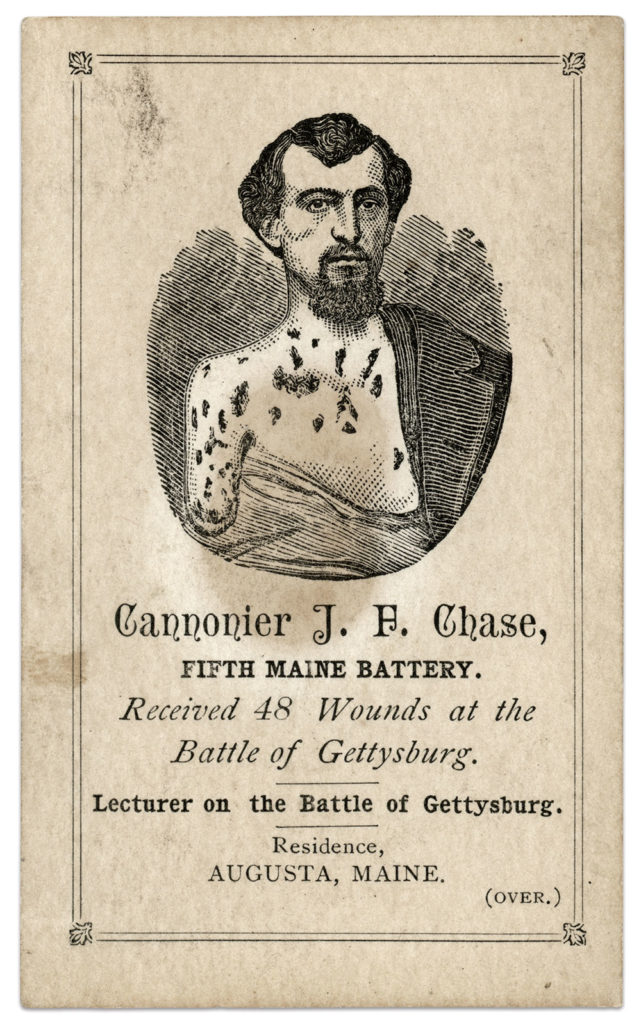

Pvt. John F. Chase

5th Maine Artillery

John F. Chase celebrated his 18th birthday by joining the army. On June 4, 1861, the strapping 6-foot tall, 160-pound young man left the family farm in Chelsea, Maine, and enlisted in Company B of the 3rd Maine Infantry. Though he entered the ranks before the First Battle of Bull Run, he received a discharge for tuberculosis ahead of that action. He returned to Maine and recovered sufficiently by early December to join the newly formed 5th Maine Artillery. His respiratory problem dogged him throughout 1862, however, necessitating another furlough home that fall. He returned to the battery in March 1863.

At the battle of Chancellorsville, Chase stayed with and serviced his gun after all but one of his crew had been killed or wounded, and then helped drag the piece off by hand. He received the Medal of Honor in 1888 for his actions.

At Gettysburg, Chase fought during the Battery’s intense action on July 1st and survived the retreat through town, ending up on a small knob of land just southeast of Cemetery Hill. It was here, as the Battery went into action against the Confederate assault on the evening of the next day, that Chase suffered a horrific wound: A canister charge exploded prematurely and tore off his right arm, blew out his left eye, and peppered his upper body with 48 pieces of shrapnel, piercing his lungs and breaking several ribs. Rendered unconscious, Chase was placed in a cart with a group of dead soldiers and taken for burial before regaining his senses. Given water by an alert attendant, the maimed artillerist’s first words reportedly were “did we win the battle?”

Taken to a farm field hospital, Chase did not receive treatment for several days. Instead, as he later wrote, “the surgeon let me lie there to ‘finish dying.’”

Against all odds, he survived. One writer estimated that Chase “received more wounds, and lived, than any other soldier in the Civil War.” By September 1, he had recovered sufficiently to be moved to the General Hospital in Philadelphia, and received his discharge a few days after President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address.

Chase returned to Maine. Although he suffered with pain the rest of his days, he went on to live a remarkable life over the next half century. An inventor, he applied for and was granted some 47 patents, from items such as an improved hoopskirt for fashionable ladies, the “Chase Bustle,” to the “Chase Aero,” a competitor to the Wright Brothers’ successful “flying machine.” Along the way he married and fathered seven children. A government pension for his military service helped him support his family.

Always seeking new means of income, Chase became involved in promoting the Gettysburg Cyclorama, and parlayed his battle scars into a side career as a successful lecturer on the painting, even though he had no firsthand knowledge of that portion of the battle. In the latter 19th century, he started a business in Gettysburg, “J.F. Chase & Co.,” manufacturing souvenir items for the tourist trade, catering especially to returning veterans. He fashioned paperweights, canes and other ephemera out of wood culled from various points on the battlefield. Such items are highly prized today.

In 1895, Chase settled in Florida, where he dabbled in real estate until 1914. He succumbed to pneumonia at the age of 71.

July 3: Early morning along the Baltimore Pike

Pvt. John H. Bearry

Battery K, 5th U.S. Artillery

Visitors to the Northern Ohio Sanitary Fair in Cleveland during the early days of March 1864 were greeted by an armless soldier. He stood near the office of The Sanitary Gazette, a veterans’ newsletter, “soliciting aid in procuring a pair of artificial limbs to replace his own which were lost at the battle of Gettysburg.” This was John H. Bearry, a 24-year-old Ohioan who had enlisted in Battery K of the 5th U.S. Artillery in December 1861.

By Gettysburg, Bearry and his fellow artillerists had become seasoned veterans who manned their four 12-pounder Napoleons under the command of 1st Lt. David H. Kinzie. The Battery belonged to the Army of the Potomac’s 12th Corps Artillery Brigade.

During the evening of July 2 at Culp’s Hill, most of the 12th Corps was moved from the position and Confederate infantry launched an assault and secured the lower crest. About 3 a.m. on July 3, the federals prepared to drive them out. Battery K, arrayed on the south side of Baltimore Pike, shelled the rebels on the hill. Later that day, the Battery was exposed to overshoots from the Confederate artillery barrage preceding Pickett’s Charge.

At some point during the 3rd, Bearry suffered severe wounds to both arms and a fractured jaw. Records are unclear about the circumstances that led to his injuries. He may have fallen victim to a faulty artillery shell that exploded prematurely during the action on Culp’s Hill, or have been a casualty of enemy artillery related to Pickett’s Charge.

Bearry landed in the 12th Corps Field Hospital at the Abraham Spangler Farm, only a few hundred yards up the Baltimore Pike from the Battery’s position. Surgeons stabilized him but were unable to save either of his arms.

By early March 1864, Bearry had returned to Ohio. Unable to use the ill-fitting artificial limbs provided by the government, and lacking funds to purchase a set that functioned better, he attended the Cleveland Sanitary Fair to raise $200 for the latter.

A letter prepared on his behalf revealed the outcome of his efforts: “I would inform those whose kindness I am so much indebted, that the proposed sum of two hundred dollars towards getting my artificial arms is subscribed. As you can never know of the sorrows into which my misfortune has plunged me—especially by the rebuffs and reproaches of disloyal men—so can you never know how your kindness has blest me; more by the proof it has given me that my labors are appreciated and that I have your sympathy, than by the very tangible assistance you have rendered me. I can do no more than express to you my heart-felt gratitude, and endeavor that your investment in my behalf shall not be a bad one.”

Bearry struggled in his quest for better artificial limbs after the promising start in Cleveland. By late 1864, he was a patient in New York City’s Central Park Hospital, known for treating soldiers in need of artificial arms. There he encountered Jacob Switzer, who had lost his right arm while fighting in the 22nd Iowa Infantry at the Third Battle of Winchester. Switzer found Bearry “very despondent and discouraged,” because he had not been able to get a good arm.

Switzer noted that Bearry finally managed to find a New York manufacturer who fabricated an arm “with which he could write, feed himself, take off or put on his hat and do almost anything that did not require use of fingers.” Within two weeks after receiving the custom device, Bearry was able to write his own letters.

Bearry moved to Iowa to start a new life. Switzer encountered him again in 1870. By then, Bearry had married and secured a postmaster position. Switzer recounted how he visited his homestead, marveling that Bearry “had stock and himself fed his pigs their slop.”

Bearry and his wife Adeline had a daughter in 1873. The family moved back to Ohio, where he died in 1891 at age 54.

July 3: Morning action on the lower south slope of Culp’s Hill

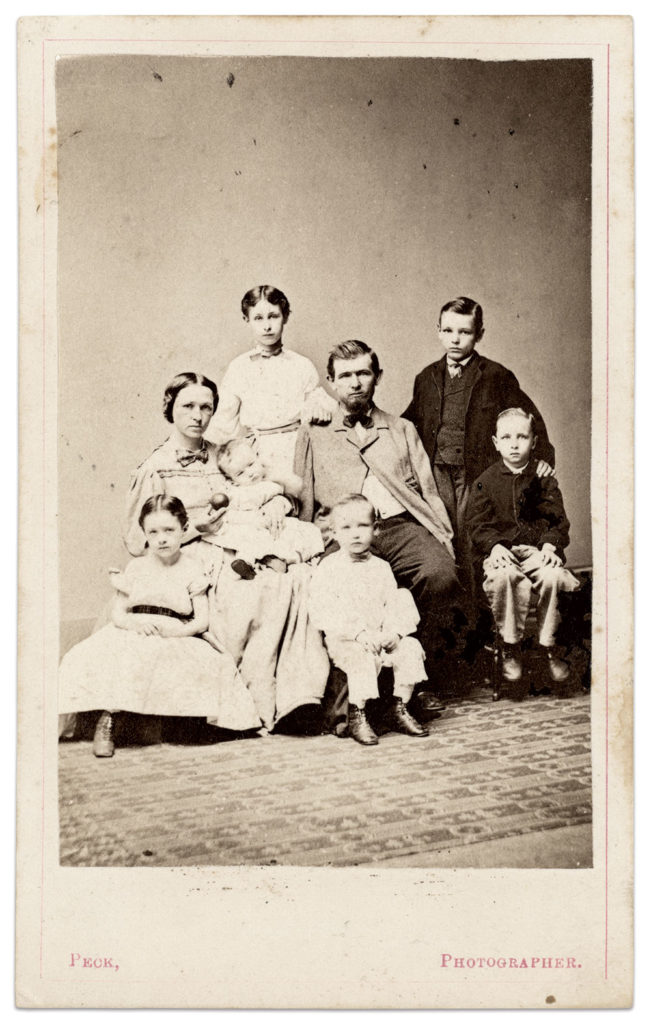

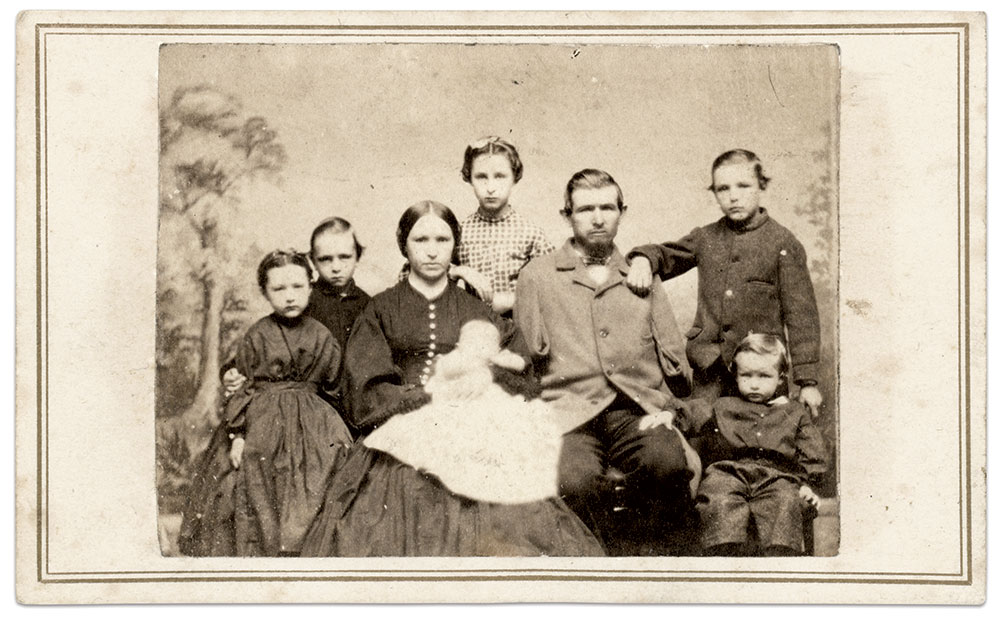

Pvt. George Warner

Company B, 20th Connecticut Infantry

During the early hours of July 3rd, after rebels captured the lower crest of Culp’s Hill, the 20th Connecticut Infantry received orders for a dangerous assignment. It was tasked to enter the woods at the foot of the hill and prevent enemy forces from flanking the right wing of federals positioned at a higher elevation. Moreover, the regiment was to act as forward observers for Union batteries keen on shelling the Confederates without hitting their own troops.

The 20th marched from its position a few rods northeast of Kinzie’s Battery of the 5th U.S. Artillery and struck the Confederates. For the next five hours, the Nutmeggers slugged it out with the 10th Virginia Infantry for possession of a stone wall. Their greatest trial, however, came at the hands of the Union gunners firing into a nearby woodlot. The historian of the 20th recalled “the sharp and almost continuous reports of the twelve pounders, the screaming, shrieking shell that went crashing the tree tops” and “the whizzing sound of the pieces as they flew in different directions.”

The commander of the brigade to which the 20th belonged, Col. Archibald L. McDougall of the 123rd New York Infantry, acknowledged that the Connecticut men fought with gallantry and did not flinch in the face of the Virginians, “enduring part of the time an afflictive and discouraging, though accidental, fire of our own batteries.”

Among the worst victims of this friendly fire was George Washington Warner, a 30-year-old peacetime millworker in Beacon Falls, Conn. He had left behind his Irish immigrant wife, Catherine, and five children a year earlier to enlist. Warner was behind a tree when an explosive projectile burst above him. According to his pension records, “one fragment struck his right arm a few inches above his shoulder—entirely severing it from the body and carrying it several feet from him.” Another jagged piece of hot metal tore into his left limb, “lacerating the soft parts badly and breaking the bones.”

Warner was carried to a nearby field hospital located at the Nathaniel Lightner Farm. Here, the regiment’s surgeon, J. Wadsworth Terry, cut off his mangled left arm within an hour after he suffered the wounds.

On July 29, Warner’s attending physician at the Lightner Field Hospital reported that the patient’s condition was good and that he slept well, though his wounds remained “quite open and discharging freely.” Warner was transported to Philadelphia to complete his recovery. In October, Catherine arrived to take her maimed husband home after the army declared him unfit for service in the Veteran Reserve Corps and discharged him.

Back in Connecticut, Warner applied for a pension. It included an affidavit by a local surgeon who assessed his case as calling for “unusual sympathy.” The doctor added, “He is entirely helpless—so far as that he cannot dress himself nor eat his food without the aid of others.” The government quickly approved the pension application, and Warner received a monthly payment of $8. In 1864, the amount increased to $25.

More than a decade later, in 1878, the amount increased to $100 after Warner submitted additional evidence of his disability. Neighbors witnessed that it was “unsafe for him to walk out from his home alone and consequently [he] is always attended by a young man,” being “entirely incapacitated from performing any act without the aid and assistance of one or more persons.”

To supplement his pension and provide for his family, which now numbered eight children, Warner sold books. He also took advantage of the carte de visite trade by marketing images of himself alone and grouped with his family. He became something of a celebrity and a living symbol of the sacrifice to save the Union. As veterans aged and monuments to their service popped up across the states, dedication ceremony organizers invited Warner to participate.

At his regiment’s Gettysburg monument unveiling in 1885, he hoisted a large American flag covering the banner by means of a rope fastened around his waist. The rope passed through a special pulley attached to the flag, which he raised by simply walking backward.

Two years later, he gripped a cord between his teeth and pulled on it to remove the draperies that covered the 110-foot Soldiers and Sailors Monument in New Haven, Conn. In 1905, he employed a similar method to uncover another Civil War monument in the city.

Warner lived until the age of 91, burying his wife and five of his children before he passed away in 1923. A year earlier, on the occasion of his 90th birthday, he expressed no remorse for the injuries he suffered in the service to his nation. “I was treated good and had plenty to eat all the time,” he reminisced, although allowing that, “there wasn’t much strawberry cake” in his diet during the years he wore Union blue.

July 3: Action at the Copse of Trees

Pvt. William B. Parker

Company I, 20th Massachusetts Infantry

In its climatic counterattack against the Virginians who breached the stone wall on the afternoon of July 3, the 20th Massachusetts Infantry lost heavily. By the end of the fight, more than half its men were casualties and its leadership decimated. Capt. Henry Abbott commanded the survivors.

Three days after the battle, Abbott wrote to his father. “When our great victory was just over,” he reflected, “the exultation was so great that one didn’t think of our fearful losses. But now I can’t help but feeling a great weight at my heart.”

Among those mourned was a 19-year-old soldier in Company I, William B. Parker. Before his enlistment, he worked as a house painter and lived with his two sisters and widowed father in Medford, Mass. A Minié ball struck Parker under his left shoulder blade and fractured the humerus. Transported to the Cotton Factory Hospital in Harrisburg, Pa., Parker came under the care of Acting Assistant Surgeon Lewis Post and a Harvard medical student, Carleton Shurtleff, who cut short his studies to serve as a medical cadet. Post removed the ball from Parker’s shoulder with the goal of saving the arm. But a radical amputation became necessary, and the surgery left an open wound that took nine months to heal. By then, Parker had been sent home, where his sister, Martha, found him “wasted away…like a skeleton.”

Unable to continue his painting profession, and unsuited to farming, Parker gamely attempted a return to military service. In 1867, he joined the 42nd U.S. Infantry, one of three regiments organized for wounded war veterans. But Parker could not stand the rigors of service and received a disability discharge soon after he enlisted. He returned to Medford a broken man, with “constant pain in his neck and shoulder” according to his pension application.

In 1869, the government approved his pension of $15 per month. But less than a year later he died of a condition described as paralysis or apoplexy. Parker was 26. His father, William G. Parker, tried to retain the pension, arguing that his son died of complications from the effects of the musket round at Gettysburg. A sympathetic surgeon supported the claim, but the Pension Office did not.

In 1880, at the age of 62, the elder Parker lived adjacent to Medford’s Hotel Simpson and was unemployed. His two daughters resided with him. Research has not yet disclosed his fate or where his maimed son was buried.

Epilogue

“The Empty Sleeve” became a catchphrase in post-war America, celebrated in popular culture, prose, poetry, and song. Sheet music published in 1866 venerated the men who had given a limb for the Union:

“Three Hearty cheers for those who lost

An arm in Freedom’s Fray

And bear about an empty sleeve

But a patriot’s heart today”

Amputees’ post-war experiences with the Northern public and its institutions were uneven, however. Success, whether measured by attaining financial comfort or securing a lasting sense of peace, had much to do with economic support, pluck and just plain luck—or the lack of it.

The men who sacrificed an arm at Gettysburg had the added cachet of incurring their loss in a fight widely viewed as the war’s turning point. Some, including John Chase and George Warner, used photography to publicize the sacrifices they made to end the war and reunite the country. Yet for too many, wounds suffered during those three days in July 1863 haunted them for the rest of their lives. In some of their portraits the pain remains plain to see, forever frozen in time.

References: General: Jordan, Marching Home: Union Veterans and their Unending Civil War; Coletti, “Heroes Come with Empty Sleeves,” americanhistory.si.edu; Brust, “Inside the Empty Sleeve,” Military Images, Spring 2020); Military service records and pension files, National Archives via Fold 3; genealogical, local, state and federal records via Ancestry; Find A Grave. For Carroll: The Indianapolis Star, Aug. 25, 1911; Ward: Korompilas, et al, “The Mangled Extremity and Attempt for Limb Salvage,” Journal of Orthopedic Surgery and Research (2009); For Craft: The Rochester Democrat, ca. July 11, 1863; The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion; U.S. House of Representatives, Mrs. Caroline G. Seyfforth, Message from the President of the United States, Returning House Bill No. 91126, with objections thereto. Aug. 10, 1888; For Chase: Dreese, The Hospital on Seminary Ridge at the Battle of Gettysburg; The Fredericksburg News, May 4, 2009; Hawthorne, John Chase of the 5th Maine Battery, Gettysburg Tour Guides; For Bearry: Sanitary Fair Gazette, Vol. I, No. II, Cleveland, March 5, 1864; Cleveland Daily Leader, March 23, 1864; “Reminiscences of Jacob C. Switzer of the 22d Iowa, Part II,” Iowa Journal of History, 1949; The Salem Daily News, June 23, 1891; For Warner: Banks, “No Sweet Dream: Remarkable Life of a Gettysburg Casualty,” John Banks’ Civil War Blog, Oct. 30, 2019; Appel, “A Hero’s Descendant Keeps History Alive,” New Haven Independent, June 18, 2012; The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies; Coco, A Vast Sea of Misery; Pfanz, Gettysburg: Culp’s & Cemetery Hill; Gottfried, Brigades of Gettysburg; Longley and Zaidel, Heroes for All Time: Connecticut Civil War Soldiers Tell Their Stories; Laino, Gettysburg Campaign Atlas; For Parker: Root and Stocker, Isn’t This Glorious!: The 15th, 19th, and 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiments at Gettysburg’s Copse of Trees.

Charles Joyce, an MI Senior Editor, focuses his collection on images of soldiers killed, wounded, or captured at the Battle of Gettysburg.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on ““Lost an Arm in Freedom’s Fray”: Union amputees after Gettysburg”

Comments are closed.