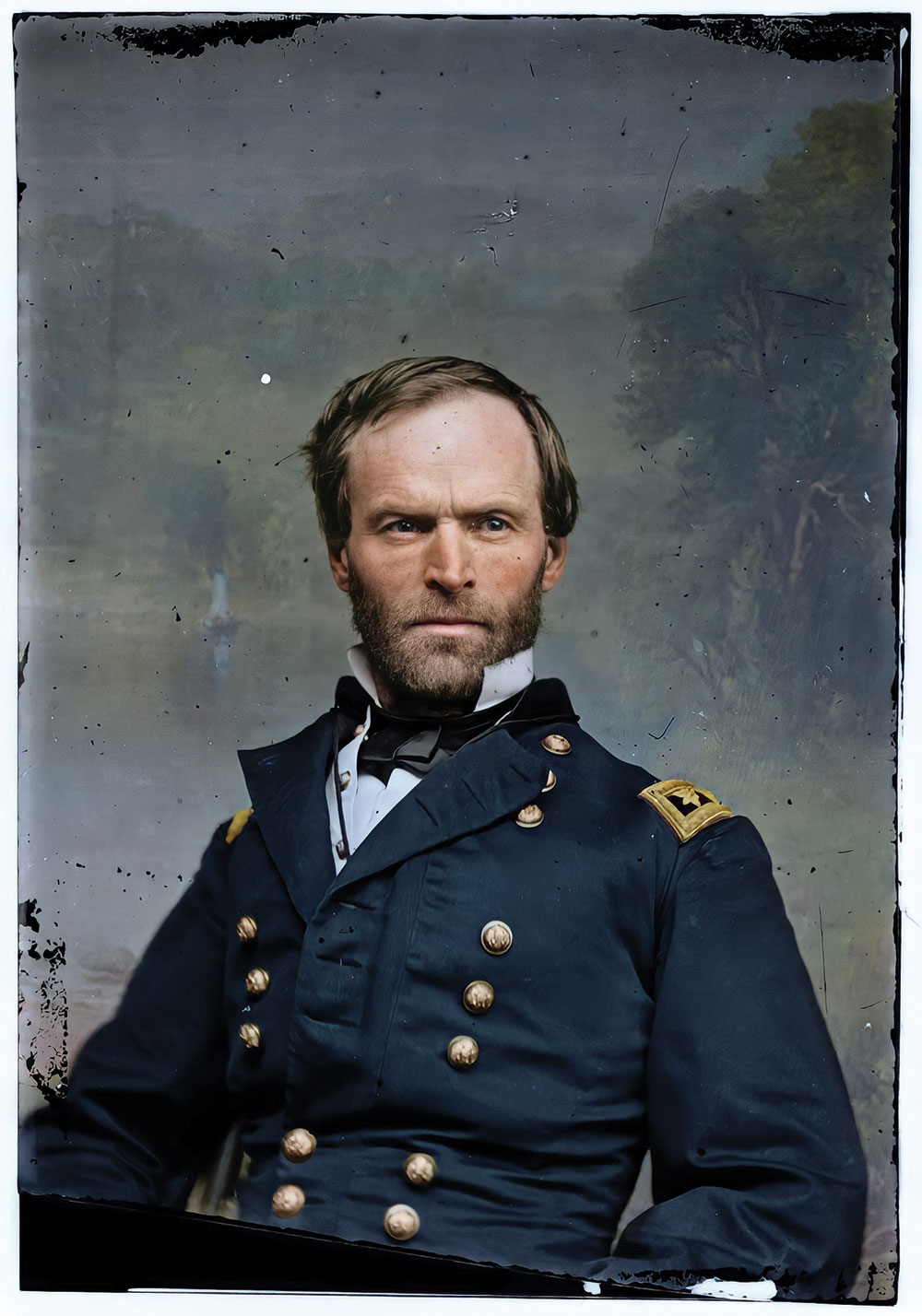

“Coloring imagery is as old as photography itself,” notes Matt Loughrey of My Colorful Past. A leader in the modern movement to colorize historic images using digital technologies, Loughrey follows in the footsteps of early photographers and colorists who applied tints directly on the surface of hard plate images and albumen prints. Loughrey uses today’s technical tools to add motion to old photos, adding a new dimension to still pictures. He does so with an artist’s eye, a mastery of technology, and a scientific method that favors what he calls “moral authenticity.”

In this exclusive MI interview, Loughrey discusses his work.

Q: What is your background, and what motivated you to start this business?

My mother and father are both from artistic and engineering backgrounds, a combination of their abilities lives on in me and as a result I fast found out I had a native skill to explore. I’ve always been around hardware, programming and art. In January of 2017 I got a call from Nina Strochlic, a writer at National Geographic, and learned that they wanted to feature my work in the magazine itself. The awareness raised enabled me to concentrate on this craft full time, and that’s when the enterprise began in full.

Q: In a layperson’s terms, describe how you colorize images.

Coloring imagery is as old as photography itself and can be approached in a handful of ways. I adopt the painter’s approach, and rather than paint the subject matter, I instead paint the light. Therein the subject matter is revealed. I take into account the degradation of an image, the medium upon which the scene is photographed, the depth of field, the fall of light, and more. This is where the key to realism lives.

Q: Do some images work better than others when coloring?

All images present their own hurdles; damage isn’t necessarily a factor in the case of workflow but more so depth of field and light fall details in the image. It’s rare that an assignment is turned away.

Q: How do you decide which colors to choose for an image? (Hair, clothing, etc.)

A lot of folks (including myself at one point) are of the belief that colorization is down to historical referencing and educated guess work. But there is a direct relationship between monochromatic shades and their corresponding hues in the red, green and blue spectrum. Exploiting the data of that relationship is a major part of my workflow when bringing an image to life.

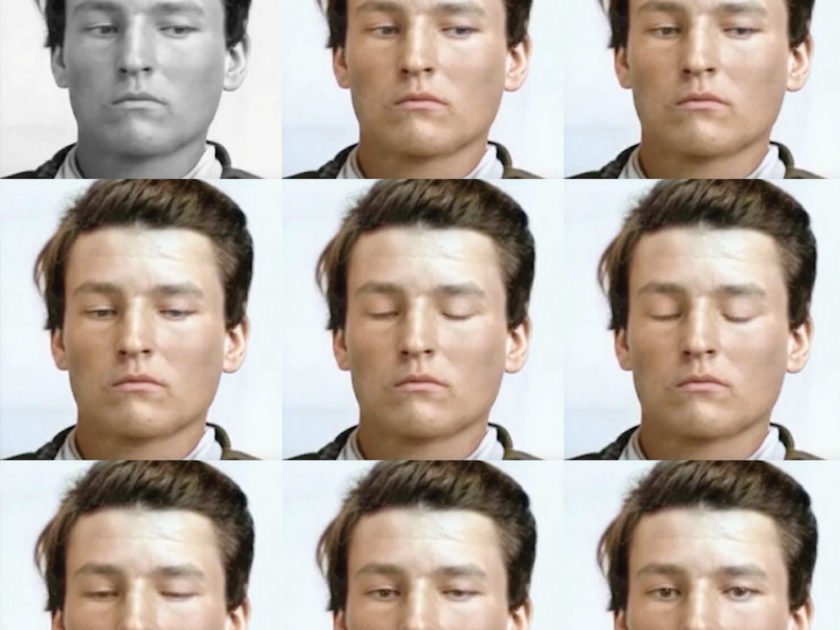

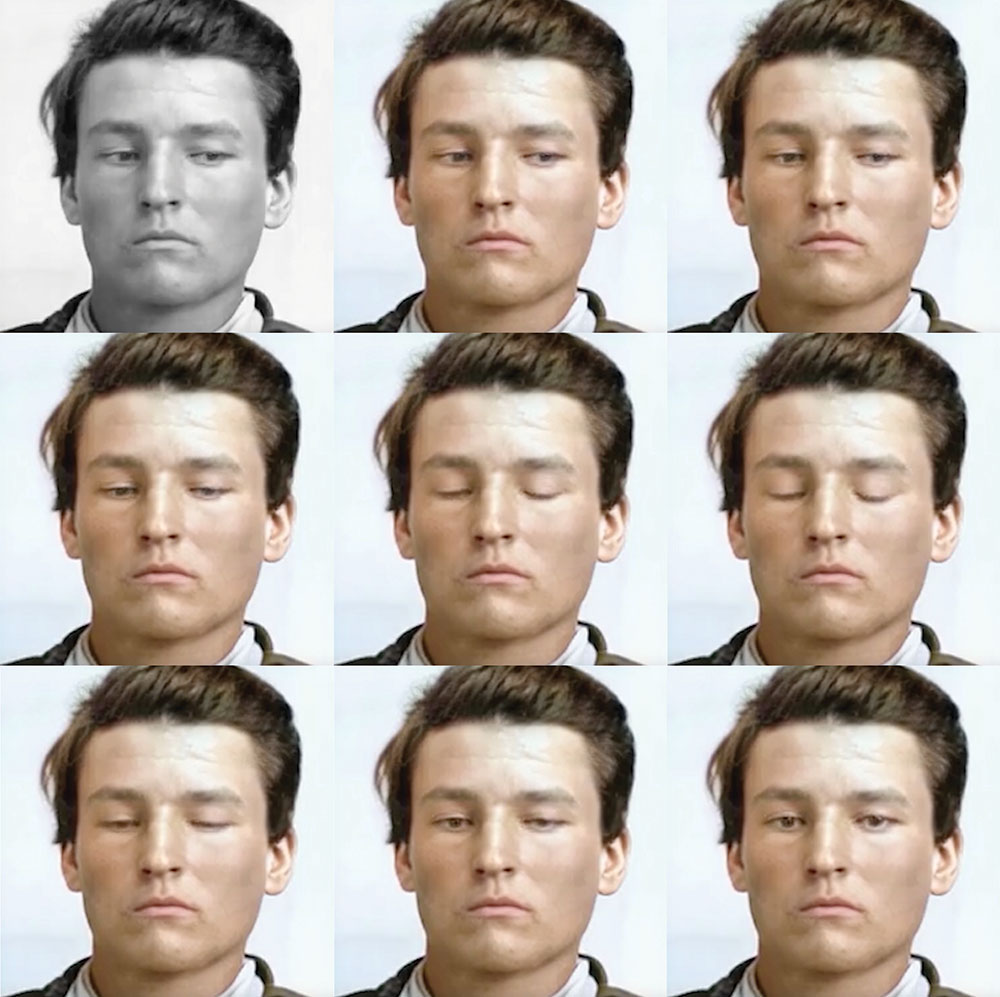

Q: It appears that you go beyond colorization: The skin appears more realistic, and then of course there is the motion in the form of blinking and slight movement. Talk about these aspects of your work.

Realism is key to ethos behind this work. Automation of and haphazard colorization of imagery do not bode well for authentic or even printable results. The solution is proprietary, and that’s what sets this project apart. With realism met, it was time to start thinking about how to add motion and that’s a project I undertook to realize in 2019. Two years later, I unveiled ‘X-Oculi,’ and it is the result of hundreds of motion-tracked datasets from true human facial expressions and movements. That information is in turn laid to the subject photograph where something very exceptional takes place.

Q: Purists are usually unhappy when they see 19th and early 20th century photographs and videos altered to appeal to modern audiences. What do you tell them?

I am fortunate to have working relationships with museums and libraries the world over, and not least the clients that come to me with photographs to realize. Publishers, boards of management and curators see the educational value in this craft as a means to engage with their readers and visitors alike, in particular the younger audience. It is arguable that we find ourselves in an age of image obsolescence with a multitude of display formats that are exceeding the use of imagery on file. Take a look at the average documentary, and when a historical image is shown it will fill only a square portion of a flat screen TV and you’re left with two black bars either side or it’s superimposed on a nondescript background. The choice is either to ‘pan-zoom’ or ‘crop-to-fill.’ Broadcast welcomes new ways to tell stories, and I believe our history deserves better, as do the producers who have engaged with my services these last few years.

Q: What else should readers of MI know about the work you do?

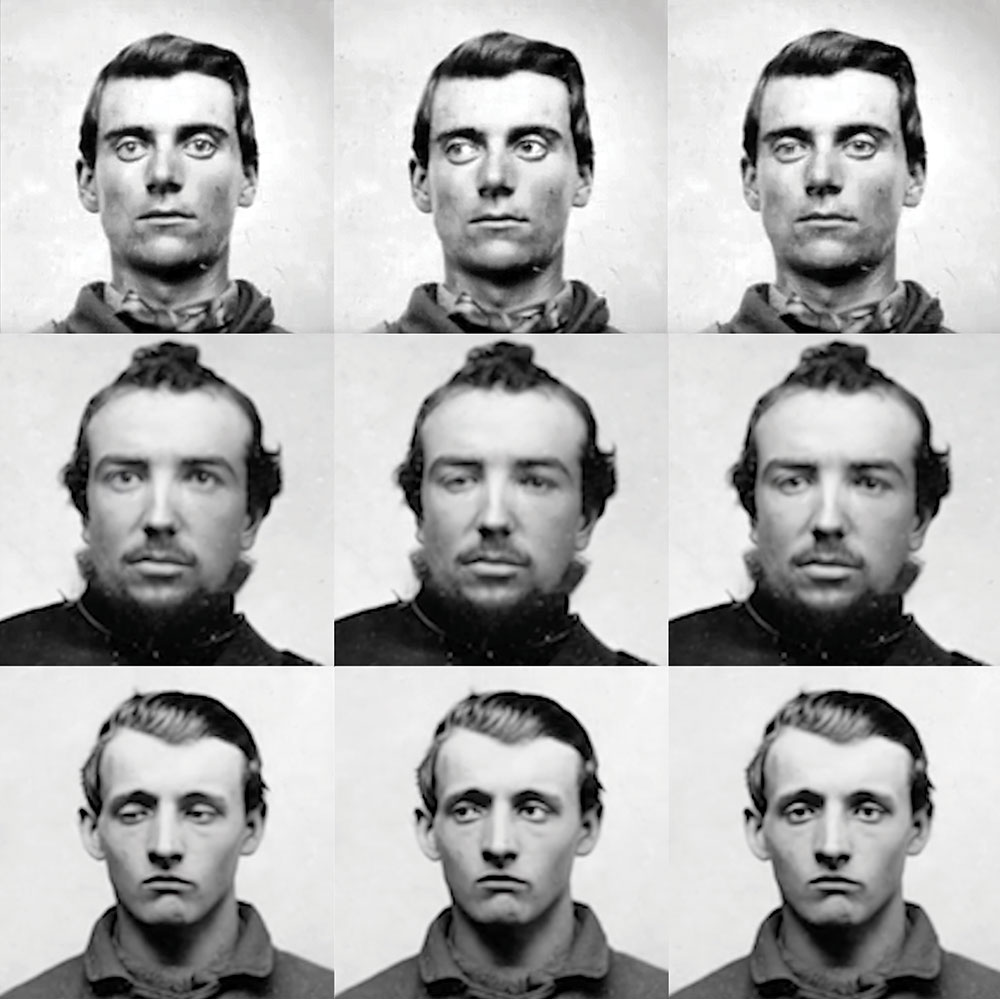

I am currently working on a non-profit assignment with present day families of Civil War soldiers. A question was raised some time ago that had me thinking about adding a further ‘moral authenticity’ to the work. In short, present day family members have provided their facial motion data (basically data taken from recordings of their own faces supplied to this very studio) to animate the faces of their relatives photographed in the 1860s. The results are ever so story-full and moreover astonishing. The project is to be documented as a story itself this year.

For more information about Loughrey’s work, visit MyColorfulPast.com.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.