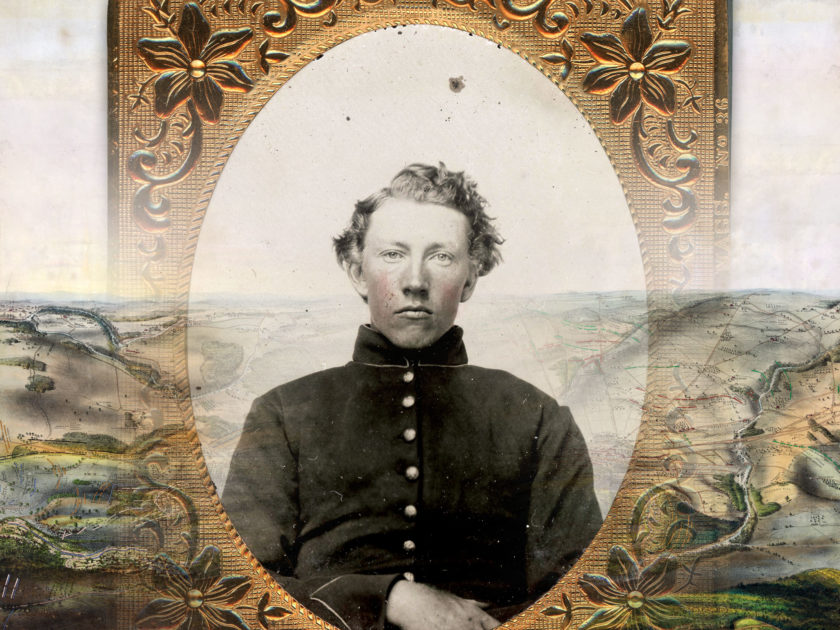

“History Will Know Him There”

Hiram Gilbert began his war service in 1861 with a mix-up. He and a number of others signed up for a three-year enlistment in the 24th New York Infantry, a two-year regiment. He reassured his anxious sister, “I shall come home when the rest of the boys do.” But when the term ended on May 29, 1863, he and the other three-years’ men transferred to the 76th New York Infantry to finish out their remaining time. He left the 24th battle-tested at Antietam and elsewhere, and with this Mathew B. Brady portrait taken early in his service.About a month after his transfer to the 76th, Gilbert and his regiment composed the advance of Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler’s brigade at Gettysburg, forming at the extreme right of the first Union battle line on McPherson’s Ridge. They were barely in position when a savage attack on their front exposed their right flank, and resulted in the loss of some 62 percent of their men in the first 20 minutes of action. Pulled back to the relative safety of Oak Ridge, the New Yorkers left behind their dead, including Gilbert.

Gilbert was shot dead, according to a letter from a sergeant in his company published in a New York newspaper, the Rome Citizen, on July 21. The editor lamented how the sad news “was rendered only more painful to the friends of the deceased by the long and anxious suspense time which had elapsed since that terrible battle on northern soil, and into which they knew his regiment was thrown,” and added, “now the decisive news that takes away the last cordial from the heart—the last hope that he may yet come back—has been received.”

The remains of Gilbert were not recovered. He likely lies in the Soldier’s National Cemetery, where at least four of the 11 graves from the 76th are marked as unknown. Or, perhaps he may be one of the estimated 1,000 dead still buried beneath the killing ground itself. The editor of the Citizen stated, “although no hand can point to the exact spot of his resting place, his epitaph is not unwritten or his fame unknown,” and added, “Mourn not then parents, brothers and sisters, friends, that he reposes in a strange land. The battlefield is a fitter burial-place for the brave than the marble vault or the quiet churchyard of his native place, for history will know him there.” —Charles Joyce

Carried Into Battle

The 2nd Bucktail Regiment, officially known as the 149th Pennsylvania Infantry, fought hard on the first day of the battle and lost heavily. When the combat ended two days later, the Pennsylvanians counted casualties—about 350 of its 450 men made the grim list.

Survivors included Pvt. Willet W. Lawrence of Company G, who carried this carte de visite with him into battle. Though the woman pictured is not named, she may be his wife, Monterey Maria Chapin Lawrence. The photo was eyewitness to Gettysburg and, according to the inscription on the back, The Wilderness, actions before Petersburg and Weldon Railroad. Shortly after this engagement, Lawrence gave the image to a cousin, perhaps for safe keeping. He needn’t have worried: Lawrence remained in uniform through June 1865, when he returned home. He lived until 1923, dying at age 82. He survived his wife by 21 years.

Briefly in Command

After the colonel of the 74th Pennsylvania Infantry was wounded during the first day’s fight, the regiment’s second-in-command, Theobold Alexander Von Mitzel, assumed its leadership. Von Mitzel, who had helped raise the regiment, had recently been promoted to major. Born and military educated in Germany, he had served as an infantry officer in the Prussian army before coming to America in the late 1850s.

Von Mitzel’s martial background served little use at Gettysburg, as he suffered a wound in the right hand early on and was captured—his second stint as a prisoner. His first, just two months earlier at the Battle of Chancellorsville, lasted 10 days before being paroled and exchanged from Richmond’s Libby Prison.

He returned to Libby Prison after Gettysburg. On Feb. 9, 1864, he joined a group of more than a hundred who escaped through a tunnel—one of the great breakouts of the war. About half made it back to the Union, including Von Mitzel. He returned to the 74th, advanced to lieutenant colonel, and served through the war’s end.

Von Mitzel settled in Baltimore, where he died at about age 52 in 1887. His wife and five children survived him.

Lost in Chaos

The 142nd Pennsylvania Infantry suffered severely as Union troops struggled to hold out against the Confederate juggernaut that tore apart their ranks during the first day of the battle. Along McPherson’s and Seminary Ridges, the 142nd left behind many of its comrades. That evening, only 80 men had survived. They laid on their arms, exhausted.

One of the absent men, Sgt. William Whaley of Company H, had received a severe wound in his right arm. A western Pennsylvania farmer, he had enlisted the previous autumn when the regiment organized with recruits from across the Keystone State.

His wound ended in an amputation. He did not survive, dying in a Baltimore hospital on July 21. He was about 29 years old.

A Request to Vote

In early October 1864 from Central Park Hospital in New York City, Victor B. Hallock of the 147th New York Infantry penned a letter to President Abraham Lincoln. Its contents tell the story of his fate in battle and his commitment to preserve the Union.

“I humbly ask a favor of you, if you please,” Hallock began. “I am a poor wounded soldier, wounded at Gettysburg July 1st 1863 in the thigh. The ball went through the muscle and cords of my leg and I haven’t done any duty since and it is as bad now as it was two months after I was wounded. It keeps breaking out. It has broke out four times now. It is going on 16 months and I am tired of staying in the hospital. They spoke of putting me in the invalid corps and I had rather not. If I am unfit for the front, why I would like to go home although I am willing to abide to your wishes but I have a home and a wife and one boy and her health is very poor. If I was fit for the front, then I should expect to stay the rest of my time, but now I am unfit for front service, I would like to go home with my family, and I would like to be home to [vote in the] election. I feel as though every Union man had ought to have interest enough in this election to do all he can to defeat the Chicago Platform. It is composed of a bad lot of men. Those men, as I look at it, don’t care for the restoration of the Union—only to compromise with the men that has tore down and trampled that flag that our forefathers fought and died for. It’s enough to make any decent man’s blood run cold.”

Hallock continued, “Mr. President, I would like to hear from you if you will stoop so low as to write to a poor soldier which I know you think a good deal of soldiers. I cast a vote for you four years ago and I expect to—if I have the privilege—to put in a vote this fall for you. I don’t do this to get my discharge but I am in earnest about it. I remain your obedient servant.”

Meanwhile in the White House, Lincoln had asked his secretaries to forward him soldier letters containing requests to be excused from duty for political reasons. Secretary John Hay selected letters by Hallock and another soldier for the President’s review. The contents likely buoyed Lincoln’s spirits during the weeks leading up to the November 8 election.

Hallock remained in uniform until April 1865. He lived until age 84, dying in 1914. —Charles Joyce

In the Sights of a Union Officer

Senior Capt. James Washington Beck and his comrades in the 44th Georgia Infantry (Doles’ Brigade, Rodes’ Division, Ewell’s Corps) helped dislodge elements of the Army of the Potomac’s worn out Eleventh Corps on July 1. While engaged with Union troops at their front that afternoon, the 44th was flanked by the 157th New York, which advanced towards their exposed right flank. Beck recounted to a Georgia newspaper a few months after the battle that the New Yorkers were “not more than forty yards” away.

Luckily for the Georgians, the federals in their front fell back, so they quickly wheeled right to face the New Yorkers. Beck and the rest of his regiment fired a volley into them. Beck remembered that, “As soon as we open fire upon the flanking party, [their] line is halted and faced to us and a most murderous volley of musketry poured into our ranks.”

The engagement escalated as both sides blasted away at close quarters. Beck recalled, “All along our line you see the boys taking deliberate aim, and every shot brings its man.” Beck observed a mounted Union officer taking deliberate aim at him, and he “fired at me with his pistol.” The shot missed. Bearing witness to this, Beck’s fellow soldiers took down his assailant, “pierced with many balls…he and his horse fall together.”

Not before long, another Georgia regiment appeared on the left flank of the New Yorkers. Thus reinforced, Beck and his men charged them. “We leap the fence and rush into the field where the hated foe is posted…[they] give way and fly, in wild dismay, and throw down their arms and yield themselves prisoners. Many, to save themselves, lie flat down on the ground, as if dead until we have passed over them.”

Two months later, Beck received a promotion to lieutenant colonel for bravery. He served until early 1865, when he went home to Georgia in poor health. He recovered, returned to his profession as a teacher, and went on to become a Baptist minister. He lived until 1908. He died in Florida, and was buried in Jackson, Ga. —August Marchetti

A Traded Rifle and a Horrible Hole

On July 1, the brigade of North Carolinians commanded by Brig. Gen. Junius Daniel deployed after receiving orders to advance. Just before Daniel’s Tar Heels stepped off, one of the general’s aides, Lt. Col. Wharton Jackson “Jack” Green spied a young lad who had just taken ill. Green traded his horse for the soldier’s rifle.

That weapon soon came in handy.

Green and the rest of Daniel’s Brigade engaged a brigade of Pennsylvania Bucktails defending McPherson Farm. Attempts to dislodge the Bucktails failed due to difficulties in navigating an unfinished railroad cut. Daniel sent Green to bring one of his regiments, the 32nd Infantry, around the right side of the cut at a low point and flank the Pennsylvanians.

Rifle in hand, Green took off on foot and brought instructions to Col. Edmund C. Brabble of the 32nd. Green remained with this regiment during the advance, offering the commander guidance in accordance to Daniel’s orders. Attempts to maneuver the treacherous cut proved unsuccessful, and Green eventually guided the men out of the cut.

As Green scrambled to leave, he leveled his rifle and fired a shot at the advancing Bucktails. He later recalled the shot was “with effect, as it caused a pause in their line behind and delayed a pouring down fire until we got out of that horrible hole.”

Shortly after Green got out, a bullet knocked him down. He had received a blow to his head. Carried to a field hospital for treatment, he landed in an ambulance train on the retreat after the battle. Union cavalry captured part of the train, including Green. He spent the rest of the war at prisoner of war camps in Fort Delaware, Del., and Johnson’s Island, Ohio.

Green survived his imprisonment and settled in Fayetteville, N.C. There, he managed a vineyard and held various political offices, including U.S. Congressman. His Recollections and Reflections: An Auto of a Half Century and More appeared in 1906. He died four years later at age 79. —August Marchetti

“The Last Thing I Remember Seeing Was the Rebel Flag”

The 151st Pennsylvania Infantry suffered 70 percent casualties in the first day’s fight. Among those on the injured list: 23-year-old Pvt. Michael Link of Reading, Pa., who suffered a life-altering wound. According to a local writer, “A minnie bullet entered at the side of his right eye, passing through his head back of the eyes and wiping out his sight forever. He fell into a ditch, where he lay in the rain for two days before he was found. Eleven days passed before his injuries were properly attended to.” He reportedly stated, “The last thing I remember seeing was the rebel flag, and I was shot just as I was leveling my gun.”

The writer added, “After Mr. Link recovered and was mustered out of service he returned to Reading, after which he entered an institution for the blind in Philadelphia. He possessed remarkable aptitude for learning and, although totally blind, soon became proficient in carpet weaving, broom making, brush making and cane seating chairs.” Turns out, he was also an expert domino player and had a unique ability to tell the time of day by the touch of his crystal-less watch.

“Blind Mike,” as he was affectionately known, died in 1899 at age 59. His wife and a number of children and grandchildren survived him.

Bayard Wilkeson, Legend

After the guns of Gettysburg fell silent, New York Times special correspondent Sam Wilkeson stood in a room of the Adams County Alms House recently filled with wounded Union soldiers. He wrote to his daughter, “I saw today a bloody mark about the size of a large man giving the outlines the human figure, that mark was made by Bayard as he lay six or eight hours dying from neglect and bleeding to death.”

Bayard Wilkeson, his son, was a 19-year-old first lieutenant in command of a battery in the 4th U.S. Artillery. During the first day’s action, he and his gunners fought along Blocher’s Knoll. Wilkeson sat astride his horse when a shell tore through the animal and his right leg. Carried to the Alms House, he cut away the remnants of his limb with a knife, and used his sash as a tourniquet.

Sam Wilkeson left the bloody spot and found his son’s corpse hastily buried in a mud pit.

On July 6, the Times published a story by Sam Wilkeson. It stands as masterpiece of American writing—and a tribute to a fallen son. It begins, “Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon a central figure of transcendingly absorbing interest—the dead body of an oldest born, crushed by a shell in a position where a battery should never have been sent, and abandoned to death in a building where surgeons dared not to stay?”

Captured While Executing Orders

As Union forces battled Confederates on the first day, Robert C. Knaggs found himself in more than one precarious position. A first lieutenant in the 7th Michigan Infantry and an aide to Brig. Gen. Henry Baxter, he rushed his commander’s orders to frontline troops.

The rebels nabbed Knaggs as he moved through the streets of Gettysburg. It was a tough break for Knaggs, who less than a year earlier at Antietam had tempted fate when he leapt off his horse, grabbed fallen colors and waved them defiantly in the face of the enemy. He managed to get away then, but not before suffering two minor bullet wounds.

Knaggs could not evade the Confederates at Gettysburg. They carted him off to Libby Prison, where he became the camp’s postmaster, and earned special privileges for good behavior. According to one report, he used his status against those who gave it to him. “Knaggs enabled many Northern prisoners to escape by not calling their names when he took the roll.”

He gained his release from Libby in March 1864, returned to the 7th, and ended his service with a captain’s brevet for gallantry. Knaggs settled in Chicago after the war, and played a role in relocating the original Libby Prison building to the Windy City, where it was operated as a museum.

Knaggs died in 1927.

Lemons and Candy

A noted forager, David Barnum of the 5th Alabama Infantry exercised his skills in Pennsylvania. “Davy” brought back a canteen of milk, butter and apple butter from Chambersburg, and shared it with his pards. At Gettysburg after the 5th participated in the rout of Union troops during the first day, he showed up with a haversack of candy, lemons and other niceties and distributed the treats to his comrades.

Truth be told, Barnum wanted to be a sailor. He had attended the U.S. Naval Academy. But the war dashed his dreams of being a navy man. A month after Gettysburg, he applied to the Confederate navy, and was accepted. By mid-1864 he had been transferred back to the 5th, as the army needed men. Barnum remained in uniform until June 1865, when he signed the oath of allegiance to the federal government. He died soon after in St. Louis, the cause of death, unknown.

Early Encounter in Familiar Territory

The 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry moved with the rest of the Army of the Potomac to counter the Confederate invasion. It arrived at Gettysburg by the end of the month. For Cpl. Wilson S. Severs and his troopers in Company F, the territory was familiar. Their company had been raised in Cumberland County, just north of Gettysburg. Severs had grown up in Dickinson Township, the youngest of five kids born to Jacob and Rachel Severs. He had spent his youth on the family farm working long hours and honing his equestrian skills.

On June 30, Severs’ Company F galloped up the Carlisle Road north of town and discovered that enemy troops occupied their very homes only a dozen miles distant.

The next morning, Severs numbered among the videttes posted on the Carlisle Road. Shortly after sunrise, Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Second Corps advanced, and a smattering of rifle-fire broke the morning stillness. The battalion to which Severs belonged, commanded by Maj. James Q. Anderson, fought stubbornly through the morning, buying precious minutes for Union infantry to arrive.

After the battle, Severs received a promotion to sergeant and, eventually, first sergeant of Company F. In the spring of 1864, before departing on the Overland Campaign, Severs posed for this likeness in his camp at Culpeper County, Va.

Much more fighting lay ahead. On Aug. 25, 1864, Severs and 17 other men in the regiment suffered wounds fighting Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s Confederates near Leetown, Va.

Severs succumbed to his injuries two days later at Sandy Hook, Md. He was a few weeks shy of his 21st birthday. His remains were interred in the family plot at Spring Hill Cemetery in Shippensburg, Pa., with his mother and two brothers who had preceded him in death. —Britt C. Isenberg

Captured after a Successful Countercharge

Union forces arrayed along Oak Ridge dealt a deathblow to the North Carolina brigade led by Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson, Jr., as it advanced during the afternoon of July 1. As the Confederate assault sputtered, the 97th New York Infantry seized the opportunity and launched a counterattack that inflicted even more damage. According to the New Yorker’s historian, “At last, when the outstretching lines and the overwhelming numbers of the enemy lapped nearly around the depleted ranks of the 97th, it was ordered to withdraw to Cemetery Hill, but too late for all to escape.”

Among the New York men who fell into enemy hands was Francis Murphy, an Irish immigrant who had helped recruit Company G, and served as its second lieutenant. Less than a year earlier at the Second Battle of Bull Run, Murphy had suffered a gunshot in the groin. This time he was uninjured, but his capture began an odyssey that took him first to Libby Prison in Richmond, then on to Macon, Ga., and Columbia, S.C. He escaped from the latter place in November 1864, and made it safely back to Union lines. He received a discharge from the army in March 1865.

After the war, Murphy became active in his regimental veterans’ association and lived until age 86. He died in 1915. His wife and six children survived him.

“With a Shout and a Solid Volley”

Capt. William Daniel Reitzel and his comrades in the 31st Pennsylvania Infantry made a timely arrival as Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles and his Third Corps faced serious trouble on the second day of the battle. A writer described the action: “This regiment reached the front on the 2d, in a crisis, when the 3d Corps was falling back before the enemy, and, with a shout and a solid volley, crossed the marshy space in front of Little Round Top, cleared the rocky face of the slope beyond, and answered the enemy’s last desperate rally by driving him into the woods.”

Reitzel suffered a wound at some point that day. Though the exact nature of the injury was unreported, it may have contributed to his dismissal on Dec. 7, 1863, for being absent without authority, misbehavior in the presence of the enemy and visiting “improper places of amusement while under medical treatment.”

The dismissal was later revoked, and he resigned. In 1864, he rejoined the army as a captain for a four-month stint in the 195th Pennsylvania Infantry, and then returned to his home and family in Lancaster County. A teacher by profession and an able writer and musician, he died in 1896 during the middle of a campaign for the state legislature on the Republican ticket. He was 63.

Unenviable Position

The 400-strong 4th Michigan Infantry battled for its life in The Wheatfield on July 2. Surrounded and hit hard by advancing Confederates, the most intense fighting occurred after the Michiganders’ color sergeant dropped the colors. The effort to retrieve them ended in a brutal melee that cost the life of the regiment’s colonel, Harrison H. Jeffords, who was bayoneted.

The casualty list of 164 included Pvt. David T. Dudley of Company C, who fell into enemy hands. Imprisoned at Belle Isle, he rapidly wasted away until he could no longer care for himself. On August 29, he received his parole and later a formal exchange. He regained his strength and returned to the 4th before the end of the year, mustering out in June 1864.

Dudley returned home to Michigan and eventually settled in Nebraska, where he died in 1912. His wife and son survived him. A friend and comrade from the 4th remembered Dudley as a good soldier who served his country well.

A First Lieutenant, Only Briefly

On the afternoon of July 2, Charles A. Foss stood with his comrades in the 72nd New York Infantry east of the Emmitsburg Road. This was 22-year-old Foss’s inaugural engagement as a first lieutenant, a promotion he received two months earlier at Chancellorsville.

Foss had started the war in the summer of 1861 as a corporal. Along the way, he worked his way up the chain of command. “I feel it is my duty to fight for my country as long as there is any chance of it being saved from ruin, so you must not think of my coming home yet,” he wrote to a brother in early 1863.

At Gettysburg, Foss and the 72nd occupied the extreme left flank of Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphrey’s division, to the immediate right of a brigade commanded by Brig. Gen. Charles K. Graham. After a Confederate attack by Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s Mississippians drove back Graham’s troops, the exposed 72nd withdrew in confusion, only to rally and join in a counterattack from Cemetery Ridge that helped drive away the Confederates.

During the action, Foss suffered a leg wound and underwent an amputation at a field hospital located on the Michael Fiscel Farm. Foss died on July 7, and was buried there in a field of clover. His remains were later reinterred in the New York section of the Gettysburg National Cemetery.

A Granite Stater Suffers His Third Battle Wound

The charge of the men and officers of the 2nd New Hampshire Infantry through Sherfy’s peach orchard on July 2 began with a yell and a 150-yard dash through the afternoon heat. Though they drove back enemy troops, success was short-lived, after brother regiments on their flanks fell back. The 2nd followed suit and withdrew. The Granite State men did so “fearfully diminished in numbers, yet firm and fearless still,” stated their colonel.

The wounded included Clark Stevens, a private in Company F. It was his third battle injury. The other two had occurred at First Bull Run, which ended in his capture and imprisonment in Richmond, and Second Bull Run, where he suffered a bullet wound. The exact location of it went unreported.

Stevens survived Gettysburg and left the regiment in 1864 to join the 1st New Hampshire Heavy Artillery as a second lieutenant. He is pictured here at this rank. After his service ended in the summer of 1865, Stevens lived in Vermont and New Hampshire. He married in 1867 and started a family that grew to include nine children. He died in 1896 at age 57. His relatively early death was attributed to his war wounds. One source noted that the bullet that hit him at Second Bull Run remained in his body. In 1901, a Grand Army of the Republic post was named in his honor.

Firefighter in the Devil’s Den

Elijah Walker of Rockland, Maine, had once been the business partner of Hiram Berry, a major general killed by a sharpshooter at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Walker was also the foreman of the Dirigo Engine Company, a firefighting outfit in his hometown.

Walker joined the army despite family obligations, namely a wife and seven children, the youngest, seven months old. He recruited 25 men of his engine company, and opened a recruiting office that signed up 80 more volunteers. He became the captain of Company B in the 4th Maine Infantry, and later advanced to command the regiment.

At Gettysburg, his men defended Devil’s Den. When Capt. James E. Smith of the 4th New York Independent Battery asked Walker to move his men to the left of the line at the Den, Walker refused. “I would not go into that den unless I was obliged to,” he said. Smith complained to Brig. Gen. Hobart Ward, who commanded the brigade. The general sent a staffer with orders for Walker to do as Smith asked. “I remonstrated with all the power of speech I could command, and only (as I then stated) obeyed because it was a military order,” Walker said.

Walker was shot during the resulting fight, the bullet almost severing his Achilles tendon and killing his horse. “Our flag was pierced by thirty-two bullets and two pieces of shell, and its staff was shot off, but Sgt. Henry O. Ripley, its bearer, did not allow the color to touch the ground, nor did he receive a scratch, though all the others of the color guard were killed or wounded,” Walker reported.

Walker survived the battle and the war, and lived until 1905. —Tom Huntington, Adapted from Maine Roads to Gettysburg (Stackpole Books, 2018)

Clearing His Regiment’s Name

The assault of Brig. Gen. William Barksdale and 1,400 of his Mississippians struck Union troops along Cemetery Ridge with the force of what seemed like a cyclone. That is, until they happened into a brigade of New Yorkers that included the Empire State’s 125th Infantry—a regiment that began its enlistment under a cloud.

Less than a year earlier, the 125th and its brigade had surrendered along with the rest of the garrison of Harper’s Ferry, Va. It was a bitter blow to the rookie regiment, which included Pvt. Charles W. Ives. He and his comrades were paroled, and spent the next two months at Camp Douglas in Chicago before a formal exchange allowed them to return to active duty—and seek a chance to clear their regiment’s name.

Redemption came at Gettysburg on July 2. The New Yorkers arrived that morning, took their assigned position along Cemetery Ridge, and sent out skirmishers, who suffered considerably. Then came the charge, which the 125th and its brigade repulsed. Confederate losses were heavy, and included Barksdale, who suffered a mortal wound and fell into enemy hands. Union casualties also ran high, and included Ives, killed at some point during the day.

Uncertain Redemption on Cemetery Hill

As darkness settled on the evening of July 2, Reuben Miller, 22, and the rest of the 153rd Pennsylvania Infantry occupied a position at the base of Cemetery Hill. The regiment had been mauled the previous day in the fields north of town, and they sought revenge. “Our forces have a good position and would rather the Rebs to make an attack,” stated one of Miller’s comrades with confidence.

They got their wish. Unbeknownst to them, three Confederate lines had emerged from Gettysburg and marched towards the Hill. They arrived in the black of night, and the Pennsylvanians were unsure if the troops moving rapidly towards them were friend or foe.

A lieutenant in the 153rd discerned them as rebels, and urged his brigade commander, Col. Leopold Von Gilsa, to give the order to fire. Von Gilsa declined, believing the advancing men to instead be federal infantry. A company commander in the 153rd nonetheless yelled “fire!” and the Union line erupted in flame and smoke. But by now, the first line of Confederates had swept past them, headed for the Union batteries on the crest. The Pennsylvanians now confronted a second line of attackers.

What happened next is unclear. A chronicler of the 153rd related that “here a promiscuous fight took place,” with “muskets being handled as clubs; rocks torn from the wall in front and thrown, fists and bayonets used.” Farther up Cemetery Hill, a Union artillery officer complained that the federal infantry in front of him “commenced running in the greatest confusion to the rear,” and “so panic stricken were they that several ran into the canister fire of my guns and were knocked over.” At some point during the action, Miller suffered a wound to his right shoulder. Taken to the Eleventh Corps Hospital at the George Spangler farm, medical personnel evacuated him to a Harrisburg hospital. During his stay, a chaplain gave him a small booklet of hymns and psalms, and Miller led the singing in his ward.

Meanwhile, the 153rd mustered out of service at the end of July. Miller received his discharge and moved to Michigan, taking up farming near the town of Constantine. He died in 1902. His tintype and psalm book, along with a metal cigar box of other family treasures, were discovered in the wall of an abandoned house in 2015. —Charles Joyce

He Brought Honor to His Regiment

The 64th New York Infantry participated in two major actions at Gettysburg—in The Wheatfield on July 2 and in the defense of Pickett’s Charge on July 3. The man pictured here, Andrus Franklin, a private in Company B, was only present for one. At some point during the engagement in The Wheatfield, he fell with a severe wound in his left leg, making him part of a grim list of 85 enlisted men killed, wounded or missing that day out of 185 engaged—46 percent of the regiment. The next day, only one man suffered a wound.

The injury ended Franklin’s combat career. He received a discharge from Harewood Hospital in Washington, D.C., less than a year later. Franklin returned to his home in Chautauqua County, N.Y., settled in Jamestown, and started a family of six children. He died on New Year’s Day 1908 at age 62.

A passage in the after-action report of the 64th is a fitting tribute to Franklin’s life and military service: “Every officer and enlisted man did his duty in such a manner as to honor himself, his regiment, his brigade, and his country.”

Captured During Barksdale’s Charge

Some historians argue that the high water mark at Gettysburg was a charge led not by George E. Pickett, but by William Barksdale. The general led his brigade of Mississippians on a charge, part of a massive assault against the Union’s left flank that broke federal lines. Barksdale’s Brigade continued forward for a mile, before being stopped and forced back with heavy casualties. Barksdale, who suffered mortal wounds, numbered among them.

The list of captured that day included 25-year-old farmer Newton J. Ragon, a private in the 13th Mississippi Infantry. He’s pictured here holding a Model 1842 musket and what appears a militia officer’s sword that dates to the 1830s. Worthy of note is his cap with an elaborately embroidered band and tassel, tinted shirt and suspenders and patterned pants with frame buckled belt—a quintessential early war Southern volunteer.

Ragon had enlisted in 1861 and suffered a wound at Maryland Heights in September 1862. His military records indicate that the nature of the wound went unrecorded, but it took him out of action for about six months. He returned to the 13th not long before Gettysburg, which proved his last battle. Ragon spent the rest of the war a prisoner and signed the oath of allegiance to the U.S. government on June 11, 1865. He returned to Mississippi, married, and started a family that grew to include four children. He died in Choctaw County, Miss., in 1907 at age 69.

Wounded at Sickles’ Gap

The half-mile gap created when Union Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles advanced his entire Third Corps ahead of their assigned place in the Union line proved an invitation to disaster. The Confederate attack that followed smashed the federals. One Union regiment caught up in the lopsided fight, the 12th New Hampshire Infantry, suffered 92 casualties.

Among the wounded was Sgt. Joseph K. Whittier. A patriotic Christian who joined the army instead of heading off to college, he had celebrated his 20th birthday just a day earlier. His injury was described as minor, and he soon rejoined his comrades. The following year, after being promoted to first lieutenant, he died at the Battle of Cold Harbor when canister shot tore through his body. The intensity of the firefight made it impossible to recover his remains, though comrades managed to retrieve his sword and pocket watch.

Words he had written home earlier in the war are a tribute to his character. “Let shame and confusion be the lot of him who at this crisis shall lift his hand, or voice, to stay the onward march of victory. Blasting infamy shall be his reward through this and coming generations.”

The Little Corporal

The men of 12th New Hampshire Infantry marched into Gettysburg only 224 strong, due to heavy losses at the recent Battle of Chancellorsville. The senior staff had all been taken out of action, leaving the regiment in command of a senior captain. The stalwarts in the ranks included Cpl. Howard Taylor of Company C, who had suffered a slight wound in his left hand at Chancellorsville. According to regimental lore, 5-foot tall Taylor was the shortest man in the 12th by a full three inches. As the story goes, he had passed his physical exam by wearing shoes fitted with extra soles.

On July 2, he and the 12th participated in heavy fighting north of the Klingel Farm. Here Taylor suffered a wound to the index finger of his right hand. The tip of the bandaged finger is just visible poking through the sling around his hand.

Taylor returned to the 12th seven weeks later. He fought on for the remainder of his enlistment, suffering a third wound—a minié bullet in his head, in May 1864, at Bermuda Hundred, Va. According to a sketch of his life in the regimental history, “This last wound, though he did not allow it to unfit him for duty but a day or two at a time, was the cause of his insanity and death, more than twenty-five years afterward. No words of eulogy, though never more deserving, can add anything to a record like his.”

Buying Time With Blood

Matthew Marvin, an orderly sergeant in the 1st Minnesota Infantry, scrawled in his diary on the morning of July 2, 1863, “this is to be the battle of the Civil War.”

What inspired this uncanny prediction from a leather goods store clerk who relocated from his native Illinois to Minnesota in 1859 is not known. His war experience was likely a key factor. Marvin had enlisted in Company K of the 1st two weeks after the fall of Fort Sumter, and suffered two wounds: In 1861 at the First Battle of Bull Run, and in 1862 during the Peninsula Campaign, when a soldier from another regiment in his brigade accidentally shot him in the thigh at Harrison’s Landing, Va.

At Gettysburg, the 1st marched into the fight just over 260 muskets strong. Marvin’s diary also included a request common to many soldiers facing death in action. “Should any person find this on the body of a soldier on the field of battle…they will confer favor on the parents of its owner by sending the book and pocket piece & silver finger ring on the left hand.”

Hours after Marvin recorded his thoughts, he and his fellow Minnesotans were called upon to make a sacrifice. Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock ordered the 1st to charge into a breach in the center of the Union line, into which 1,600 Alabamians were also charging. Hancock hoped the Minnesota men could buy him time while he brought up reinforcements.

The Minnesotans ran down a slight slope toward the rebels. Marvin suffered a wound early in the action when a bullet tore through his right foot, entering next to the big toe and exiting through the heel. Nevertheless, Marvin got up and continued the assault, later explaining, “No rebel line could stand a charg of my Regt & if the Bayonet must be used I wanted a chance in as it was free to all.”

Just as Marvin caught up with the rest of his comrades, he collapsed from loss of blood and crawled back to Union lines on his hands and knees. He wrote that night that he “was in awfull pane” and “of all the suffering that I have ever had I believe that this has beat them all.”

Meanwhile, the Minnesotan’s audacious charge succeeded in throwing back the Alabamians and saving the Union center at a horrible cost—some 80 percent casualties.

Marvin survived, though the painful and troublesome wound ended his service. Transferred first to Philadelphia and on to Illinois, where his parents still lived, he received a discharge in June 1864. About this time, he posed for this likeness in Chicago. His prized finger ring is visible on the pinkie of his left hand. —Charles Joyce

Action With Zook’s Brigade

In late 1861, New York City passenger tram driver Daniel Banta left his wife, infant son, and joined the 66th New York Infantry. He started as a private and rapidly rose through the ranks to sergeant major. He served in this capacity during the December 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, where the 66th futilely hurled itself against the stonewall. The regiment’s after-action report lauded Banta for standing preeminent among the ranks.

Seven months later at Gettysburg, Banta, now a first lieutenant, led his men into combat on July 2. The 66th and the rest of its brigade, commanded by Brig. Gen. Samuel Zook, moved upon a small wooded and rock studded eminence on the Union left called Stony Hill. There, Zook’s men engaged Confederate Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw’s brigade of South Carolinians. In the ensuing fierce fight, both Zook and Banta received gunshot wounds to the abdomen—injuries almost invariably deemed fatal. Zook succumbed the next day.

In Banta’s case, a minié bullet tore through the fleshy part of his right arm just below the shoulder, continued through the right lung, diaphragm and intestines, and exited his left side near the spine. Carried to the Second Corps Hospital, according to military records, he suffered days of “vomiting and involuntary evacuations,” spitting up “bloody and rust colored” fluid with “fecal matter escaping through [his] abdominal orifice.” The bullet paralyzed his right arm.

Over the next two weeks, medical personnel kept him in a quiet place, and administered generous doses of opium or morphine every two hours. At the end of that time, though his arm remained non-functional, he was able to sit up in his bed. Furloughed and sent home to convalesce, Banta posed for this portrait, with pain evident on his face.

He returned to the 66th in March 1864, physicians reported, “unable to do any duty, but enjoying a comfortable state of health.” The same doctors presented his case to the New York Medico-Legal Society “to show that punctured wounds of the abdomen are not necessarily fatal.”

Days later, Banta received a discharge and resumed his life and job in New York City. By 1879, his old war wounds forced him to leave his job. He died five years later, at age 50. —Charles Joyce

Misadventure and Missed Opportunity

As Pickett’s Charge erupted during the afternoon of July 3, a much smaller operation unfolded about eight miles west in the village of Fairfield. There, the 6th U.S. Cavalry rode into town to plunder Confederate wagons and seize Fairfield Pass—one of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s principal retreat routes.

One of the troopers in the saddle that day, Cpl. James M. Sturgeon, an ex-boatman from Erie, Pa., had enlisted in the regiment following the First Battle of Bull Run. In the early spring of 1863, Sturgeon posed for this portrait near the Army of the Potomac’s winter headquarters. The photographer who captured Sturgeon’s likeness was none other than James F. Gibson, one of Mathew B. Brady’s talented team of lensmen.

A few months later at Gettysburg, Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt dispatched Sturgeon and the roughly 400-strong 6th in response to a civilian’s report about an unguarded rebel supply train in Fairfield. Upon its arrival, the 6th ran into elements of a Confederate brigade commanded by ill-tempered William E. “Grumble” Jones.

The ensuing battle initially favored the Union. Sturgeon and his comrades, part of a squadron led by 1st Lt. Tattnall Paulding, fought dismounted from the protection of a fenced ridgeline. They blunted a charge by the 7th Virginia Cavalry with deadly fire from the muzzles of their .52 caliber carbines. Then, the 6th’s major ordered Paulding’s squadron to pursue the defeated foe.

As they saddled up, the balance of Jones’ brigade came up, drew sabers and attacked. Unable to reach their horses in time, Paulding’s men were overrun by saber-swinging rebels. “My men were scattered through the field, and being pursued by the mounted foe were soon captured,” Paulding reported. Prisoners included Paulding and Sturgeon, along with over half of the troopers of the 6th. Lee’s vital artery of retreat remained open.

Sturgeon gained his release and returned to his regiment by its muster out in July 1864. He eventually married and moved around, farming in Wisconsin in 1870 and trying his hand in the Colorado Silver mines in the 1880s, He returned to farming life in Riverside, Calif., by the turn of the century. In 1908, suffering senility and various physical ailments, he entered the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers near Los Angeles. He died there two years later, leaving 34 cents to his name. —Charles Joyce

The Sacrifice of an Irish Woman

Mary Ann O’Connor experienced tragedy after she emigrated from County Lough, Ireland, to Philadelphia in the early 1840s. Her husband, Richard, went off to fight for his adopted country during the Mexican War and never came home. His loss left her a widow with a young son, Patrick, who had been born in their homeland.

Flash forward to the Civil War. Patrick, now a confectioner’s apprentice, earned as much as $5 a week, the lion’s share of which went to support his mother. In September, he followed his father’s footsteps and volunteered to fight for his country. He enlisted in the 69th Pennsylvania Infantry. Standing just shy of 6-feet, he was the tallest man in Company K.

At some point during his service, O’Connor posed for this portrait with a cigar between his lips. His hat, a “beehive” or plug style, worn at a rakish angle, was popular in the regiment.

At Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 3, O’Connor stood in line of battle with 33 other members of his company near the far left of the 69th’s position. When Pickett’s Charge crested at the angle to their right, the rebels broke through that portion of the line. The Confederate attackers swallowed up the rightmost company and forced others to bend back.

O’Connor and Company K, did not bend back. A lieutenant in Company D explained, “we were determined that as long as a man lived he would stand and be killed too rather than have it said that we left on the battle field in Pennsylvania the laurels that we so dearly won in strange states.” Among those who paid the price was O’Connor, killed by a musket ball to the lungs.

His body was brought home to Philadelphia and buried for free in a tract at the Old Cathedral Cemetery in the western part of the city, along with some 80 of his comrades. The graves were unmarked, and his exact resting place remains unknown. His mother received an army pension in 1865, and her death date is not known. —Charles Joyce

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.