By James S. Brust

Memories of the unthinkable carnage of the Civil War were kept fresh for the remainder of the 19th century and beyond by the vast number of amputees whose life changing sacrifice was always visible. Various internet sources place the number of amputations performed during the conflict at between 30,000 and 60,000. Performed to save lives from the destructiveness of Minié balls and flying shrapnel, such surgeries succeeded in a significant percentage. They also left many American communities with heroic veterans who bore the scars of a lost limb.

A number of high-profile amputees bore the suffering well. Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles ceremoniously sent his shattered right leg to the newly founded Army Medical Museum in Washington, D.C., and visited it yearly thereafter. The typical Civil War veteran who lost a limb, however, unlikely handled it with such aplomb.

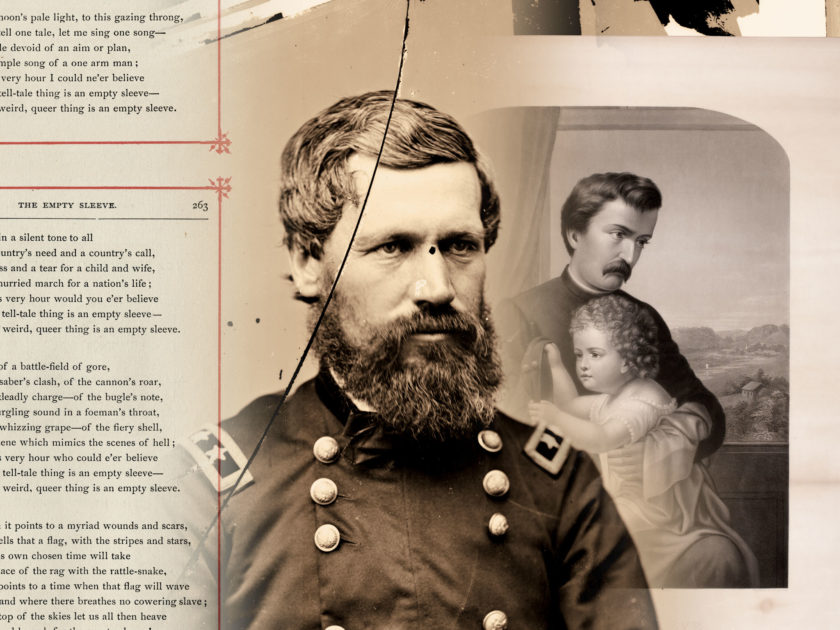

Another high-profile amputee, Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, suffered two shots in the right arm at the Battle of Fair Oaks, Va., on June 1, 1862. He underwent surgery, the shattered arm removed above the elbow. He could not have tolerated it better, and his amputation is best remembered for a lighthearted anecdote rather than any disability it caused. Maj. Gen. Philip Kearny called on Howard the next day, himself an amputee who had lost his left arm in the Mexican War. He consoled Howard by saying “General, I am sorry for you; but you must not mind it; the ladies will not think less of you!” Howard laughed and replied: “There is one thing we can do General, we can buy our gloves together!”

Howard returned to active duty, finished the war, and received the Medal of Honor for the battle that cost him his arm. He went on to become commissioner of the Freedman’s Bureau, rejoin the Army for arduous campaigns during the Indian Wars, serve as superintendent of West Point, and play a role in the founding of Howard University.

His lifetime of activity and achievement suggest he never dwelled on life as an amputee. However, his participation in an event just a month and a half after the loss of his arm touched off a chain of events in popular culture that resonated with the typical amputee and their families.

In July 1862, the month following the loss of his arm at Fair Oaks, Howard toured his home state of Maine, speaking in support of the Union war effort and Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, the commander of the Army of the Potomac. Howard urged citizens to volunteer for the war.

One of those citizens, David Barker (1816-1874) of Exeter, listened to Howard speak in Bangor, on Wednesday evening, July 16, 1862. The well-liked Barker worked as a teacher, attorney, and eventually a legislator. He is best remembered for his poetry. Impressed by Howard’s speechmaking, and what he described as the “silent eloquence of that empty sleeve,” he penned a poem, which appeared in the local newspaper shortly thereafter.

Barker’s poem entered the popular culture—and in today’s terms, went viral. In 1864, publisher W.W. Whitney in Toledo, Ohio, released sheet music of a song by Henry Badger titled “The Empty Sleeve.” Barker’s poem comprised the lyrics, though used without credit.

Another artist touched by Barker’s verse was Adelaide R. Sawyer (1831-1916) of Worcester County, Mass. She visualized the poem in an image published in 1866 as an engraving titled, “The Empty Sleeve” by J.C. Buttre of New York City. The print’s subtitle, “What a tell-tale thing is an Empty Sleeve,” leaves no doubt that Barker’s poem inspired the artwork. But there is no mention of either the poet or the general. From this point on, this and similar images seem to have lost all connection to Howard.

As often the case in the 1860s and 1870s, popular art was copied in the carte de visite format. Such images, commonly known today as fillers, were inexpensively mass-produced by enterprising photographers who copied lithographs and engravings without permission, and often without attribution. This pirating of art and photography was common and received little censure. In essence, this was done without regard for intellectual property rights. Pirated cartes anonymously spread Sawyer’s image to a wider audience.

One photographer, George P. Critcherson of Worcester, Mass, recreated Sawyer’s drawing using real actors. This required more effort and likely more expense than re-photographing the engraving. The approach was executed far less frequently, and seems likely reserved for more popular subjects. None of the Critcherson cartes include a reference to Barker or Howard.

Even the poem itself became disconnected from Maj. Gen. Howard. A handsomely produced retrospective of Barker’s work, containing 130 poems, was published in 1886. “The Empty Sleeve” received a two-page spread that included a crude version of Adelaide Sawyer’s drawing, but without mentioning Howard.

The Oliver Otis Howard Collection at Howard University contains two copies of the poem. The cataloging information however, inaccurately lists the poem as “Me Empty Sleeve.”

It is difficult to imagine a man who handled the loss of an arm as bravely as Howard. No indication exists that he shared the forlorn look on the face of the veteran in Sawyer’s image. Still, many identified with the emotions mirrored that same expression. Barker numbered among them, even though his inspiration came from the courageous Howard.

References: Howard, Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Major General United States Army; Portland Daily Press (Maine), July 18, 1862; Poems by David Barker; Portland Daily Press (Maine), Aug. 22, 1862; Brust, “Filler Cartes de Visite: A fresh look at art, humor, and satire.” Military Images (Autumn 2019).

James S. Brust is a collector/researcher/writer specializing in 19th century popular prints and photographs. He is coauthor, along with Brian Pohanka and Sandy Barnard, of Where Custer Fell, Photographs of the Little Bighorn Battlefield Then and Now(University of Oklahoma, 2005), and wrote “Filler Cartes de Visite” in the Autumn 2019 issue of MI. With an interest also in medical history, he contributed the essay “A Psychiatrist Looks at Mary Lincoln,” to The Mary Lincoln Enigma: Historians on America’s Most Controversial First Lady, (Southern Illinois University, 2012). He lives San Pedro, Calif.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.