By Richard Leisenring Jr.

After the death of Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth in 1861, patriotic Northerners eager to remember his martyrdom purchased a huge number of cartes de visite featuring his image. The assassination of President Abraham Lincoln four years later prompted a similar reaction.

These likenesses of Ellsworth and Lincoln are the best-known examples of a little-explored genre of Civil War images—memorial photographs. The larger part of this group is not photos of the famous, but personal- or private-issued images of the common soldier and sailor.

These unique photographs are worthy of further study.

The creation of the memorial photograph in the United States can be loosely attributed to Mathew B. Brady. After a decade as a photographic artist creating portraits of prominent people, he caught on to the idea as photographs as a way for the average person to preserve or memorialize a loved one. Acting on this hunch, Brady began advertising in 1856 in various New York newspapers: “Never delay the important business of getting your Portrait; you cannot tell how soon it may be too late.” The not-so-subtle message alerted Americans to have photographs made of themselves and family while it was still at all earthly possible. In a related ad Brady called on people to have photos of deceased friends copied.

Other studios immediately followed suit. But little did they realize that what started as a way for photographers to add to their bottom line would become a form of immortality.

After the Civil War began, the eager recruits who enlisted in the armies had their images taken in a variety of formats. These young men were motivated to possess a souvenir of their service or give copies to family, friends and loved ones. And as casualty lists grew beyond the wildest imagination, the portraits of soldiers represented the last tangible proof that they lived—a form of immortality. These images were replicated and shared with others helping to soften the grief. And thus, this new category that Brady advertised became a crucial part of the American memory.

Memorial photographs are rooted in a standard funeral custom that made its way from Europe to the United States in the early 19th century—the memorial card. Ranging from simple cards to fancy works of art, these cards possessed various bits of information regarding the deceased (age, time and place of death, etc.), available at funeral or memorial services through the undertaker. On occasion, they were mailed as an obituary or death notice.

This custom expanded to include photographs of the departed to create the memorial photograph. The introduction of the carte de visite in 1859 made photographs easily reproduceable, sharable and less expensive compared to the alternative daguerreotypes, ambrotypes and tintypes. A lasting memorial could now be created quickly and on a large scale. In the case of Ellsworth, Lincoln and other popular figures, the production and mass marketing heralded a new era of social media that radically altered the customs and practices of the day.

Memorial photographs generally share several distinguishing features. All were produced from images of the subject taken while living (not to be confused with post mortem photos taken after death). Their name, military affiliation and other information, including where and when they fell in battle, typically appear on the card mount. Appropriate phrases of respect, such as “In Memory of” or “Requiescat in Pace” (Latin for Rest in Peace), and traditional black mourning borders are sometimes included. In some cases, the image was applied to a commercially produced, ornate memorial card specially designed to combine the two elements.

Evidence suggests that the majority of memorial photographs of enlisted men, non-commissioned officers and commissioned officers were privately distributed in limited runs in the North. In some cases, the practice spread from grieving families to local communities, and after the war to veterans’ organizations. By contrast, fundraisers used the images of national heroes and martyrs to benefit philanthropy and commercial ventures, and provide revenue to the photographers who produced them.

Such photographs in the South were practically non-existent, essentially due to the scarcity of materials and photographers to do the work.

The existence of these images are easy to spot due to the characteristics outlined here. But what about those who simply took the last known portrait of their loved one or comrade to the local photographer’s studio and had copies made without any memorial embellishment? We may never know how extensive memorial photographs were in practice.

Another question arises regarding memorial photographs that do not share the common characteristics. How does one tell memorial photographs apart from portraits of those who survived?

The easiest way to tell if a portrait falls into this category is to compare the time the photograph was produced to the time of death of the subject. (Remember, the memorial photograph was a copy made after death.) The telltale signs to look for include the presence of a tax stamp used from Aug. 1, 1864, to Aug. 1, 1866, and/or the cancellation date on the stamp if evident. In some instances a copyright date for either the card mount or the photo is a great help. The address and history of the photographer are instrumental in discerning the time it was made. As a caution, period writing on the photograph regarding the death of the subject is not always an indication the image was produced as a memorial. It may have been added later to a pre-existing photograph as an afterthought.

Also, don’t forget or discount identified images of military men in civilian attire. Not all soldiers had time to pose in uniform before heading off to war. With a little research, you may find the man just may have an impressive war record and if fallen in battle, the image may have been printed as a memorial. If not, you still have a photograph of a veteran who may have been forgotten to history.

Memorial photographs could also be combined with an obituary or death notice. The U.S. Christian Commission offered a template for family or friends to fill out.

Cartes de visite with ornate oval printed frames are often mistakenly labeled as memorial photographs. Studios offered such designs as upgrades for their customers. While some customers may have selected this design to remember a deceased veteran, they are not exclusive to the memorial genre.

During and after the war, photographers continued to produce memorial photographs as cartes de visite and albumen prints, and later as cabinet cards. By the 1880s, photographic establishments specialized solely in memorial photographs in the cabinet format, to meet the high demand. These businesses advertised just as Brady did in the 1850s. Many used a 19th century form of direct marketing: They trolled newspaper obituaries, then sent catalogs and samples to grieving families. All one needed to do was pick a suitable design that met the needs of the family, and include a photograph for copying.

Issued in various forms, depending on the photographic and printing methods in vogue at the time, memorial photographs reached a pinnacle in the United States around World War I, and fell out of style shortly after. Some social historians suggest this decline resulted from advances in medicine that increased life longevity. The introduction of personal cameras, introduced in the late 19th century and came into their own in the early 20th century, allowed anyone to create a personal keepsake. Though the memorial photograph remains available to some extent today, its cousin, the memorial card, continues its purpose as a standard for contemporary funerals.

More scholarship can help us better understand and appreciate the role of memorial photographs in American culture, particularly during the Civil War and postwar periods. But as this introductory exploration and the accompanying gallery show, further study can unearth data for future historians, and contribute insights into our relationship with death.

References: New York Times, Sept. 4 and Oct. 6, 1856; Democrat and Chronicle, Dec. 25, 1888; burnsarchives.com; Burns, Sleeping Beauty: Memorial Photography in America; Manseau, The Apparitionists: A Tale of Phantoms, Fraud, Photography.

Richard Leisenring Jr., a native of Hopkinsville, Ky., has been an avid collector of Civil War memorabilia since 1967. He has worked in the museum field and as an historical consultant for 42 years, the last 15 as curator of the Glenn H. Curtiss Museum in Hammondsport, N.Y.

Formal Cards: Photographs with custom typeset card mounts

The growing spiritualism movement in the war weary North is reflected in this second generation memorial photograph of Col. Ellsworth. According to an exchange of letters printed on the back, the photography firm of Jeremiah Gurney & Son first published this portrait soon after Ellsworth received his death wound in May 1861, after he hauled down a Confederate flag from an inn in Alexandria, Va.

More than 2-years later in the autumn of 1863, Richard D. Goodwin happened upon the image in the photo album of a lady friend. He spotted, or thought he spotted, a ghostlike impression of “a beautiful classic head of the Goddess of Liberty” next to Ellsworth’s face. He then discovered much to his astonishment other faces in the image.

Goodwin, a New York City businessman who adopted the title of colonel after a failed attempt to raise an infantry regiment, had a dubious background. In 1862, he had been described as a dishonest imbecile that had spent time in an Empire State penitentiary after his testimony during a Congressional Court of Inquiry investigation into the conduct of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell at the Second Battle of Manassas.

Gurney’s business instincts likely trumped any concerns about Goodwin’s character when it republished this carte described in the fine print as “The Mysterious Likeness of Col. Ellsworth, and Letters” in 1863. The copyright is in the name of M.E. Goodwin, likely a relative.

Pvt. Frederick Beal Crocker and his comrades in the 37th Massachusetts Infantry occupied a section of the Petersburg line opposite the Confederates on June 20, 1864. According to the regimental historian, “At this point the two lines of works were separated by scarcely more than a hundred yards in some parts, the opposing lines grimly watching each other through the following day with an occasional outbreak of sharp-shooting.” An enemy marksman took out one Bay State boy that day—Crocker. The peacetime carpenter was 28 years old. The circumstances of his death appear on the card.

The individual who wrote the poignant “History of a Picture” printed on the back of this carte does not identify the soldier posed with his children. His name may have been omitted out of respect for the late man’s family, or perhaps because the story was untrue. The same story also appears in late December 1865 in the Buffalo Commercial of Buffalo, N.Y., the location of Evans’ studio.

Join the rebel army or go to prison was the stark choice faced by Pvt. Walter S. Personett of the 2nd New Jersey Cavalry, according to a printed obituary attached to the back of his portrait. He chose the latter, and paid the ultimate price when he died at Andersonville on Oct. 1, 1864. The notice does not mention that he succumbed to diarrhea. The dimensions of the printed paper and the thin black rules that border it suggest that it was specifically designed for cartes de visite.

Mortally wounded during the Second Battle of Manassas in August 1862, Capt. William E. Tysinger of the 1st Virginia Infantry reportedly uttered the last words prominently imprinted on his portrait. Tysinger began his service as a first sergeant and earned his promotion to captain a few months before his death. A revenue stamp on the back of the mount bears a hand-cancelled date of June 9, 1866. Pictured in civilian clothes, he possibly did not pose in Confederate uniform before his death.

It comes as no surprise that Mathew Brady entered into the memorial card market, as evidenced by this elegantly typeset carte of Noel Byron Phillips. A private in the 4th Maine Light Artillery, he died in action during the Battle of Cedar Mountain, Va., in August 1862. His life was the only one lost in the battery during the engagement, a Confederate victory.

Informal Cards: Non-typeset images made after death, confirmed by an analysis of names, dates, inscriptions, back marks and service records.

Following the death of John Burns in 1872, photographer Levi Mumper produced this memorial image of the Hero of Gettysburg. A carte de visite of Burns attached to a bayonet is at the center of the artful composition. The bayonet leans against an infantry drum and is surrounded by a cap, a cane that likely belonged to Burns, drum sticks, a cartridge box and Starr carbine. All of these items, except the cane and photo, may have been relics picked up off the battlefield.

Belfield “Bell” Atkins and his comrades in the 63rd Indiana Infantry occupied the front line of their brigade in a charge across an open field on May 14, 1864, at Resaca, Ga. They managed to capture a portion of the enemy’s works despite a heavy fire. The Indiana boys suffered 18 killed, including Atkins, and 94 wounded. Later that year, his hometown photographer produced the memorial photograph based on an earlier tintype. The photographer improvised a shelf out of books to steady the image—a novel and artful solution.

New York City photographer Richard A. Lewis created a variation on the memorial photograph when he packaged a soldier’s likeness with his death notice. The result bears a resemblance to 20th century press photographs. In this case, the soldier is Capt. Eugene Macy Deming of the 61st New York Infantry. The son of a brigadier general of Illinois state troops who died before the Civil War, Deming suffered a leg wound and fell into enemy hands during the June 30, 1862, action at Charles City Crossroads, on the sixth day of the Seven Days’ Battles. Surgeons amputated the leg, and he succumbed to its effects in Richmond on July 19. A death notice similar in substance and style appeared in the Aug. 1, 1862, edition of the New York Times.

A woman is reunited with a soldier in this double exposure made during the 1870s. Photographers used this technique to various effects, including the genre known as spirit photography. Depending on the exact date this image was produced, she may be his wife or mother.

Charlotte Brown, the “Mother of the 100th New York Infantry,” distributed this cabinet card at a regimental reunion about 1875. The soldier was her husband, James Malcolm Brown, the colonel and commander of the 100th. He died in action at the Battle of Fair Oaks, Va., on May 31, 1862. Charlotte died in 1899.

Col. George Duncan Wells of the 34th Massachusetts Infantry suffered a mortal wound during a reconnaissance in the Shenandoah Valley near Fisher’s Hill on Oct. 13, 1864. The dying Wells ordered his men to abandon him. At least two of his troops stayed behind, and all three were captured. One of them reported, “I found the Colonel sinking very fast. Placing him upon a blanket, we carried him back to the hill from which the Rebel batteries were still playing upon our retreating comrades.” They soon encountered Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal Early, who asked about the identity of the wounded man. After being informed, he ordered an ambulance. Wells expired just as his comrades placed him into the wagon. His body was returned under a flag of truce. The 1865 copyright date on the front establishes it as a memorial photograph.

This postwar copy print of a tintype held in place by nails affixed to a fabric-covered surface is further distinguished by an inscription on the back, added by a nephew in memory of his Uncle Casper. He was Pvt. Casper Miller Coiner, an overseer prior to the war who served in Company E of the 1st Virginia Cavalry. Wounded at Kelly’s Ford in 1863 and again at an unnamed engagement in March 1864, he was killed in action on May 24, 1864, at the Battle of Kennon’s Landing, also known as Wilson’s Wharf, located along the James River near Charles City, Va. Coiner sits next to his older, bearded brother Elijah, who served in the same company and regiment. Elijah advanced to the rank of second lieutenant and survived the war. After, he returned to his hometown of Waynesboro, and lived until 1915.

Levi W. Hunt died on March 3, 1865. The inscription by a patriotic hand paid tribute to his service. The ornate oval frame surrounding Hunt lends mourning aesthetic to the image, though the decorative border was not common to memorial images. The lack of a revenue stamp, mandated by law between August 1864 and August 1866, indicates that this image was produced either before or after the soldier died, suggesting two scenarios. The image may have been taken before Hunt died, and a family member, friend or comrade inscribed the mount with the grim fact. Or, it was produced after August 1866 from an original negative or an existing portrait.

During the fighting at Deep Bottom Run, Va., on Aug. 16, 1864, Lt. Col. Thomas Albert Henderson of the 7th New Hampshire Infantry suffered a severe hip wound. He died the same day. This image can be considered a memorial photograph for two reasons. A revenue stamp on the back of the mount is dated Oct. 10, 1864—two months after his death. Also, Henderson appears as a first lieutenant, a rank he held from 1861-1862.

Wounded and captured at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill, Va., in June 1862, Lt. Col. Edwin Smith Gilbert of the 25th New York Infantry gained his release a few weeks later. Sent home to recuperate, he died in early 1863. Research reveals that the photographer, J.B. Roberts, took over the Rochester, N.Y., gallery of B.F. Powelson in mid-1864—a full year after the death of Gilbert. The original photograph is believed to have been taken by Powelson and reprinted by Roberts. This is a textbook example where the history of the photographer helps date the image.

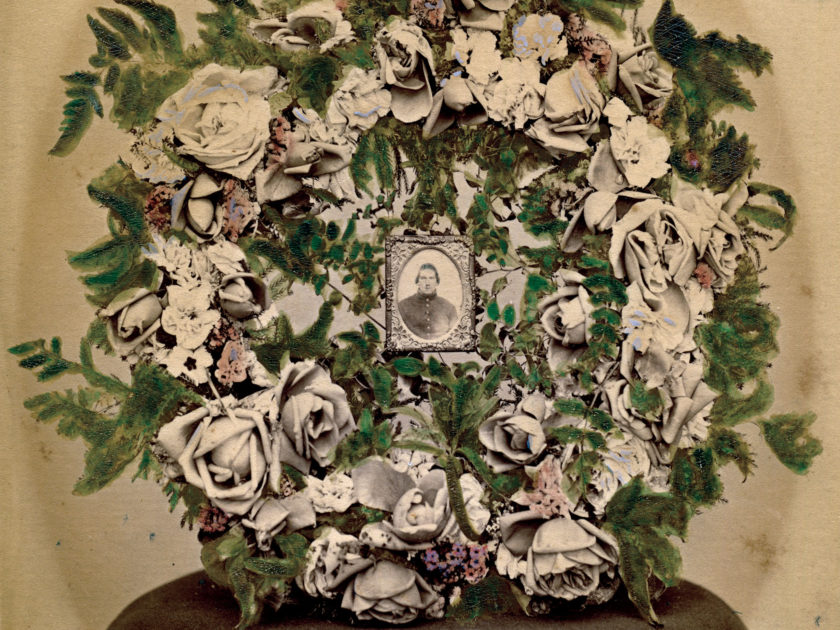

Mourning Wreaths: Arrangements of lilies, carnations, roses and other florals are traditional mourning symbols

An original tintype or ambrotype of a federal soldier occupies the center of this arrangement.

This circa 1870 image features what appears to be an albumen print retouched in charcoal or color tints.

It is not known whether this bespectacled Union field grade officer died by disease, a wound or another cause.

Unverified Cards: These images exhibit some hallmarks of memorial photos. But the lack of a name, date or other information prevents an airtight conclusion.

The photographer who made this copy print of an unnamed Union infantry officer used a simple technique common to lensmen of the period—the original portrait, a tintype in this case, was tacked to a board with nails to steady the image and then photographed. The decorative mount is not specific to memorial photographs, but merely a style popular at the time. Another unknown is this man’s fate. He may have died, and the family reproduced this likeness to create a memorial photo. Or he may have lived, and they ordered copies to remember his time in uniform. The metal regimental number 7 attached to his cap offers a clue to his identity.

In St. Johnsbury, Vt., photographer Franklin B. Gage printed a gentle, yet grim, reminder of the value of memorial photographs: “Persons having a small picture of any friend lost in battle, can have it enlarged to any size of finished into a splendid portrait. They can also be made from card negatives. These pictures make the most pleasing mementoes that can be preserved of those who have laid down their lives for the nation’s welfare.”

One of those men is pictured here. Capt. Joseph Wead Dickinson Carpenter died in The Wilderness on May 5, 1864. According to a history of St. Johnsbury, Carpenter “was struck by a musket ball in the left breast, while, it is supposed, he was leaning forward endeavoring to discover the position of the foe. He fell forward upon his face, and although approached almost immediately thereafter by comrades, and raised, life was found to be extinct.” His newlywed wife, Helen, survived him. Whether this print was made before or after Carpenter died is not known. At least one other image of a soldier, who survived the war, is known with this back mark, suggesting that the note was an advertisement and not a memorial photo.

The name of the Confederate in this portrait taken by an Alabama photographer is currently lost to history. An unknown hand recorded his death date, Oct. 19, 1864, below his likeness. He may have been among the Alabamians lost in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley during the Battle of Cedar Creek.

Was the date added by a comrade or a loved one to this existing print, or did the photographer produce a new print that was dated? If it was the latter, this image could be labeled a memorial photograph.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more