By Dr. Anthony Hodges

Though the guns of war fell silent in April 1865, business continued to boom for Robert M. and James B. Linn’s photograph gallery on Lookout Mountain. A sizable contingent of garrison troops in Chattanooga, and tens of thousands of veterans passing through the city on their way home, provided a steady customer base. The numbers included a group of troopers from the 4th Michigan Cavalry that had participated in the capture of Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Georgia. The Michiganders took a compass from Davis, and sold the relic to James.

A year later however, the situation had dramatically changed. The troops had mostly disappeared. Despite the loss of a large part of the base, enough people still ascended Lookout Mountain to take in the natural scenery, and keep the studio open.

In an effort to expand their business, the Linn brothers opened a studio in downtown Chattanooga sometime around or just after war’s end. Cartes de visite from this studio are distinguished by back mark of the Mountain City Gallery. The rarity of surviving cartes with this mark leads one to conclude this gallery could not have operated for very long.

There were other changes during the early post-war years. An informal survey of extant images indicates that scenery and landscapes, especially of the mountain’s battlefield, took precedence over the portrait business. The brothers began to spell their name Lynn instead of Linn for an unexplained reason. The change may relate to Robert’s use of Royan at various times during his career—though the author has never seen this name variation printed on a photograph.

Robert eventually returned to Ohio, where he died of influenza in 1872. Shortly after his death, Linn’s Lookout Landscape Photography manual was published in Philadelphia. His sons, George Thomas and Earnest H. Linn, became the wards of his brother James, who continued in the Lookout Mountain business. In 1880, George joined his uncle as a photographer at Gallery Point Lookout.

Chattanooga, a small fledgling railroad town in 1861, became a bustling city during the post-war years. The area’s resources and industrial potential attracted Union and Confederate veterans, some of whom had become familiar with Chattanooga from wartime campaigns. The city went so far as to run advertisements in Northern newspapers that read, “Wanted any number of Carpetbaggers to come to Chattanooga and settle…as the jurisdiction of the Ku Klux and other such vermin do not extend over these parts… Those having capital, brains, or muscle preferred.” Newcomers included Indianan John T. Wilder, who commanded the famous Spencer rifle-armed “Lightning Brigade” of the Army of the Cumberland. He developed much industry in the area, and even briefly served as Chattanooga’s mayor. Old Yankees and rebels were often business partners, social friends and political allies in post-war Chattanooga.

Given the lack of sectional animosity and the old battlefields around the city, Chattanooga ranked among the first sites considered for reunions. In 1881, a mere 16 years after the war, Union veteran gathered for the Society of the Army of the Cumberland reunion. One of the main events was a dinner hosted by the “The Society of Ex-Confederates” of Chattanooga.

The ex-Cumberland soldiers returned in 1889 and invited the old Confederates to join them at a great barbecue on the old battleground of Chickamauga. More than 20,000 veterans from both sides attended the event, as well as thousands of non-veterans. The barbecue promoted the idea of making the old battlefield into a Chickamauga Memorial, a federally-supported park, with the lines of both armies appropriately marked and monumented. Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans spoke on behalf of the North, and Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon for the South. At the conclusion of the barbecue, each veteran smoked a pipe of peace composed of wood from the Chickamauga battlefield and attended an organizational meeting of the Chickamauga Memorial Association.

In August 1895, the old veterans realized a dream when the Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park was dedicated, the nation’s first.

In August 1895, the old veterans realized a dream when the Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park was dedicated, the nation’s first. The park drew hundreds of reunions and meetings over the next four decades. The first national reunion of ex-Confederates, the United Confederate Veterans (U.C.V.) was held in the city in July 1890. The U.C.V. returned again in 1913, 1921, 1934, 1942 and 1945.

In 1913, Chattanooga hosted the national encampments of the U.C.V. and the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R).

Untold numbers of smaller reunions were held in the city, including subdivisions of the larger veterans’ groups, monument and marker dedications, and sons and daughters organizations.

Fortunately for James and his nephew George, many of the aging veterans desired to visit Lookout and have their portraits taken, just as they had done in the old days. Unfortunately for them, the Linns lost their lease at the Point in 1886 to the Hardie Brothers of Michigan. So they opened a studio on Sunset Rock, a large ledge outcropping on the mountain’s western brow. Despite the relocation, many veterans sought out the Linns, possibly out of loyalty.

The Linns returned to The Point in 1899 and operated their business from a small studio. The bulk of the work fell on George, as his Uncle James dabbled in real estate. James passed away at age 77 in 1922. George continued to oversee Gallery Point Lookout until 1938, passing away three years later.

In 1939, the National Park Service approved the building of the Ochs Museum and Observatory atop the old Linn studio. Its namesake, the late newspaper publisher Adolph Simon Ochs, had once owned the New York Times and Chattanooga Times. Today, the museum contains a small exhibit on the Linns, and copies of some of their wartime portraits. The last direct male descendant of the Linns of Lookout in the Chattanooga area passed away in 1995.

Safety reasons no longer allow access to The Point. The Friends of Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park and National Park Service make Umbrella Rock, adjacent to the Point, available for photographs as part of an annual fundraiser.

References: Walker, Lookout, The Story of a Mountain; Govan and Livingood, The Chattanooga Country 1540-1976; Hoobler, Cities Under the Gun; Free Press (Chattanooga), Aug. 31, 1997; Twentieth Reunion, Society of the Army of the Cumberland, September 1889; Smith, A Chickamauga Memorial; Baumgartner and Strayer, Echoes of Battle: The Struggle for Chattanooga; National Park Service interpretive panel, Ochs Museum.

Dr. Anthony Hodges is a Color Bearer of the American Battlefield Trust and serves as steward of the October 1863 Brown’s Ferry Battlefield for the Trust.

Gallery of images

“Returning from the war, June 5, 1865.” These five cavalry officers were about to end their war service when they posed for this group portrait. Two of the troopers served in the 4th Michigan Cavalry, which had just a month earlier captured President Jefferson Davis in Irwinville, Ga.: Maj. Briggs L. Eldredge, far left, and Maj. Robert Burns, far right. Both were on their way to Nashville, where they mustered out on July 1. The three officers in the middle all belonged to the 4th Ohio Cavalry, and they were also on the way to Nashville to muster out. From the left: Captains Greenleaf Cilley and Thomas H. Osborn, and Surg. Orestes G. Field.

“Returning from the war, June 5, 1865.” These five cavalry officers were about to end their war service when they posed for this group portrait. Two of the troopers served in the 4th Michigan Cavalry, which had just a month earlier captured President Jefferson Davis in Irwinville, Ga.: Maj. Briggs L. Eldredge, far left, and Maj. Robert Burns, far right. Both were on their way to Nashville, where they mustered out on July 1. The three officers in the middle all belonged to the 4th Ohio Cavalry, and they were also on the way to Nashville to muster out. From the left: Captains Greenleaf Cilley and Thomas H. Osborn, and Surg. Orestes G. Field.

This image remains in much use today, perhaps more than any other Linn photo, by the Tennessee Valley Authority to promote flood control through its chain of dams along the Tennessee River. The stereo card pictures The Great Flood of 1867—the largest in the city’s history, during which floodwaters rose more than 50 feet in Chattanooga. Though the death toll went unrecorded, witnesses reported corpses floating down the streets.

Henry V. Boynton, second from left, never missed an opportunity to promote his brainchild, Chickamauga Park, whether in newspaper editorials or by escorting dignitaries on battlefield tours. In this photo, he accompanies military and congressional dignitaries to Lookout, with a stop at the Linn gallery along the way. Boynton received the Medal of Honor for his actions at Missionary Ridge, and went on to serve as a brigadier general of volunteers during the 1898 War with Spain. One of Boynton’s guests, Brig. Gen. Lewis A. Grant of the 5th Vermont Infantry, second from right, received the nation’s highest military honor for gallantry at Salem Heights, Va.

George Washington “Wash” Shaw, leaning against Umbrella Rock, led this group of young men, perhaps sons of veterans, on a guided tour. Shaw, also known as “Liveryman No. 1,” was born in Georgia in 1867. He handed out this business card to advertise his services.

The birth of the battlefield preservation movement is captured atop Sunset Rock, as a group of veterans and dignitaries pose for the Linns at their relocated studio during the 1889 Army of the Cumberland Reunion. Henry Van Ness Boynton (1835-1905), seated, front row, fifth from the right, formerly lieutenant colonel of the 35th Ohio Infantry, conceived the idea of Chickamauga National Park as he rode about the battlefield in preparation for this reunion. Boynton advocated for Chickamauga Park, and served as its first historian, He is considered the father of Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park. Directly behind Boynton stands Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, and to his right is Col. John T. Wilder of the famed “Lightning Brigade.” At this reunion, which included the so-called largest barbecue ever held in the South and a symbolic smoking of the pipe of peace, Boynton and others began a process that culminated with the Park’s dedication in 1895. The model they conceived became the basis for all subsequent battlefield preservation.

A group of Confederate veterans and family members are perched upon Umbrella Rock in this photograph, most likely taken at the May 1913 United Confederate Veterans national reunion. Only one individual is identified: C.B. Mullens, who sits with a pair of crutches in the lower-right hand corner of the frame.

Wig-wagging signal flags from mountain top to mountain top emerged as a critical method of communication for the Army of the Cumberland trapped in Chattanooga following the 1863 Battle of Chickamauga. These Signal Corps veterans commemorated their contribution to victory when they returned to Umbrella Rock and once again sent signals—and have their portrait made.

The Linns made this tintype of Francis West, former colonel of the 31st Wisconsin Infantry, seated, at the Sunset Rock studio during the 1889 Army of the Cumberland reunion. In a letter to his wife on the reunion’s first day, West reported immense crowds at the reunion parade, and a planned trip to Lookout Mountain the next day.

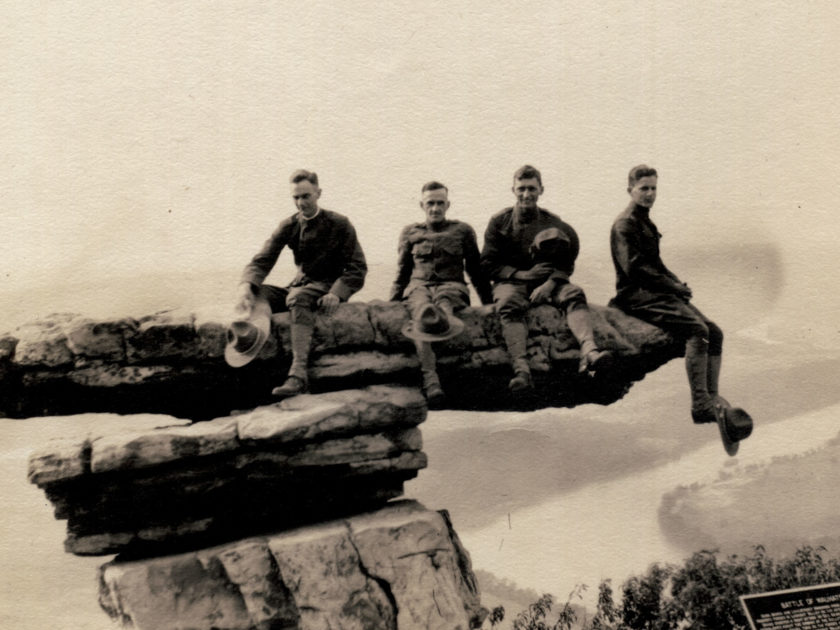

Chickamauga Park served as a training camp during the Spanish American War and both World Wars. These images picture the sons and grandsons of Civil War veterans posed atop Lookout, much as their forebears had in bygone days. Park officials closed the Point by World War II, preventing GIs from continuing what had become a time-honored tradition.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.