By Ronald S. Coddington

Veterans have always told war stories. Those who survived the Civil War were no exception, and they number among the earliest to recall their service through photography.

The preservation of these images by the veterans began soon after the war ended. Massachusetts officers Arnold A. Rand of the 4th Cavalry and Albert Ordway of the 24th Infantry assembled the best-known collection. It is fair to characterize Rand and Ordway as among the first military image collectors. The portraits and original negatives they obtained formed the collection of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS) Massachusetts Commandery.

Far less is known about another veteran, however, who amassed thousands of Civil War images, behind the scenes with no fanfare.

Left for dead, his adjutant, a Harvard classmate, discovered Lawrence, and managed to get him into an ambulance.

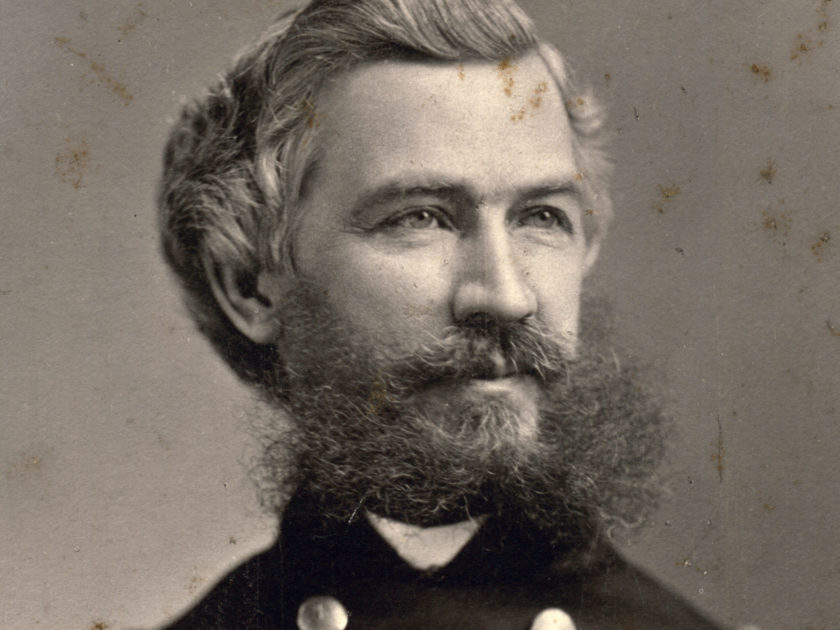

Samuel Crocker Lawrence, a quiet man of generous spirit, had been enamored with soldiering since his boyhood in the Boston suburb of Medford. After graduating from Harvard in 1855, he became involved with the local militia, the Lawrence Light Guard. The company was named for his father, a prosperous rum distiller and scion of the community. As the nation drifted towards war, young Lawrence prepared accordingly. In late 1860, he tapped into his family wealth and social position to rent a hall above a Boston railroad station to drill his troops. By this time, he ranked as colonel of the state’s 5th Militia.

The men of the 5th, with Lawrence in command, departed for Washington when the war came. The 5th arrived in the U.S. capital a few days after its brother regiment, the 6th, had endured rough treatment from pro-secession mobs as it marched through Baltimore.

In Washington, Lawrence’s regiment became known as the “Steady Fifth” for its gentlemanly conduct and soldierly bearing—the officers and enlisted men taking cues from their colonel. The regiment lived up to the reputation on the slopes of Henry House Hill during the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861. The 5th went into action, even though its enlistment had expired.

An eyewitness account quoted in the regimental history recalled the performance of the 5th that day.

“I saw the Mass. Fifth in their dark uniform and their steady advance under the enemy’s fire of shot and shell; I noticed them some distance off; they came into the field by a flank movement, and then into column, with as much coolness as if they had been on an ordinary muster-field. They had to pass over an open field exposed to the full force of the rebel batteries, but they did not waver in the least. On the brow of the hill I first saw their Colonel [Lawrence] at their head. He is a tall and slim man, with dark hair. He is quite young, not more than twenty-five. They took their places and fought bravely.”

In fact, Lawrence was 28 years old when he led his men into the fight. The 5th was eventually driven from its position. About this time, an artillery shell crashed into a tree and sent splinters tearing into Lawrence’s side. Left for dead, his adjutant, a Harvard classmate, discovered Lawrence, and managed to get him into an ambulance. Caught in the skedaddle to Washington, Lawrence eventually made it to the capital, though the ambulance was abandoned along the way.

The injuries ended Lawrence’s active duty, and he left the military service in 1864 as a brigadier general in the Massachusetts Militia.

His life after the war was marked by business success and a reluctance to enter politics, despite the urging of friends. Finally, in 1892, he consented to become a candidate for the first mayoral race in his hometown of Medford and won handily on the Republican ticket. But he had no taste for the job, and served only a single term. He preferred to move in philanthropic circles, where his generosity funded numerous initiatives that supported the local community. His death at age 78 in 1911 was widely mourned.

Lawrence left a fortune estimated in the millions, and a will that designated bequests to various organizations, which he was associated during his lifetime.

Among his personal effects was a collection of 3,680 Civil War photographs that included albums of cartes de visite and unmounted prints of camp scenes and battlefields by the studios of Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner. How Lawrence came into possession of so many photographs is unclear. We do know that he was a collector by nature. He had a passion for books, especially local and military histories and volumes related to his Masonic brethren.

He also collected artwork. According to a biographical sketch published a year before his death, he decorated the Lawrence Light Guard Armory with examples from his collection. “In the various rooms of the Armory he has hung many pictures, representing a great variety of subjects, paintings, engravings and prints, many of which are very rare.” The prints to which the writer referred might have been Civil War photographs.

His photo collection came into the custody of the Lawrence Light Guard in 1911. Years later, in 1948, the Guard donated a small wooden chest filled with the images to the Medford Historical Society. The chest eventually moved to the top floor of the Society’s building, which served as headquarters and museum.

Years passed and interest waned in the chest and its contents. But the Society remained a vibrant organization. In the 1980s, the Society became a frequent destination for school class trips. The teacher who organized the visits, Arlene Diamond Generazzo, happened to be vice president of the Society. She recalled one student in particular, fourth grader Chris Dennen, who participated in one trip and came away fascinated by the Civil War artifacts on display. He visited again as a sixth grader and became even more impressed. This was about 1990.

When the young Dennen returned home after the second trip, he told his dad what he had seen. Robert Edward “Noah” Dennen, a Civil War buff and an avid reader of books on the subject, was intrigued.

“Noah was really into the civil war,” observed Generazzo. “I got to know him as a person and a friend. He was a really nice guy. He was a family man.”

“You could see pimples on people’s skin and dirt clogs. They looked like I had reached into the photographer’s 1862 camera and taken them out.”

Hartford Courant staff writer Trish Davis interviewed Dennen in 2000, two years before his death. Davis reported, “Dennen became a society member, and after a few months was told he’d find a few photos chronicling Civil War life in the building’s attic.”

The photos were still in the chest, which Generazzo described as very small in size. “A guy could carry it under his arm with one hand. It had several drawers. The pictures and were jammed inside in tight little rolls.”

Mike Bradford manned the desk at the Society on the day Dennen stopped by to see the photos. “Typical civil war buff, big collection of books,” Bradford recalled. He escorted Dennen upstairs to examine the chest, and remembered that, “He paid great attention to the photos.”

Generazzo also noted, “Nobody appreciated the value until Noah came along.”

Dennen shared some observations about the photos in the Hartford Courant interview. “You could see pimples on people’s skin and dirt clogs. They looked like I had reached into the photographer’s 1862 camera and taken them out.”

The president of the Society, Dr. Joseph Valeriani, recalled Dennen’s reaction in a written statement a few years later. “Astonished by the number and quality of the photographs and the fact that he had never seen many of them before, Mr. Dennen quickly suspected that the collection might be of interest to Civil War historians. He invited Brian Pohanka, an expert on the Civil War, to view the photographs, and six hours later, black to the elbow with dust and dirt, Mr. Pohanka confirmed Mr. Dennen’s suspicion: the chest contained one of the largest and finest collections of Civil War photographs in existence.”

Pohanka, a noted historian, battlefield preservationist and regular contributor to Military Images prior to his passing in 2005, played a crucial role in establishing the importance of the collection.

Before long, news of Dennen’s discovery spread like wildfire after announcements appeared in the Boston Globe and Civil War Times. Perhaps the high-water mark of media attention occurred in 1994 with the publication of Landscapes of the Civil War: Newly Discovered Photographs from the Medford Historical Society. Edited by Constance Sullivan, the volume features nearly 100 images from the collection, all in pristine condition.

Following the publication of Landscapes, the collection was showcased in curated exhibits. For the past 20 years, access to the collection has been restricted, as a preservation plan was developed.

Current Society President John W. Anderson offered an upbeat assessment of the collection’s future, which involves a comprehensive digital effort.

“We’re proud to be stewards of this wonderful and important collection,” Anderson said. “For decades, it was forgotten and neglected. After it resurfaced in the 1990s, we found ways to make it available on a smaller scale and made sure it was properly preserved. By digitizing all the images, we want to bring the collection out of off-site secure storage and make it available online to researchers, genealogists, and Civil War enthusiasts.”

The job of bringing it online falls to Allison Andrews, the Digitization Project Manager.

“Cataloging the collection was the milestone that opened up possibilities for understanding and using the images, since now we had an overall inventory as well as an identifier for each individual image and a sorting mechanism,” she said. “For our dedicated team of volunteer catalogers and professional advisors, working with the original prints was a remarkable and often moving experience.”

Andrews added that, “The digitization phase is underway, and in the coming months the images will be posted on Digital Commonwealth, a local history-sharing platform. We are excited to share the photos with the world, and to do this without retrieving the original prints from off-site storage and subjecting them to wear and tear accomplishes a conservation goal as well.”

In January 2017, MI was granted access to the collection. In coming issues, you’ll see examples from the holdings of a pioneer Civil War photo collector. The images pictured here are a selection of well-known camp scenes.

References: Constance Sullivan, editor, Landscapes of the Civil War; Alfred S. Roe, The Fifth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in Its Three Tours of Duty 1861, 1862-’63, 1864; The Harvard Graduates’ Magazine, Volume XX, 1911-1912; Medford Historical Society, Historical Register, 1909; John H. Hooper, Proceedings of the Celebration of the Two Hundred and Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the Settlement of Medford, Massachusetts; Tyler Keystone, Oct. 20, 1911; George W. Nason, Minute Men of ’61; Telephone interviews with Arlene Diamond Generazzo and Mike Bradford, June 6, 2017; Hartford Courant, Sept. 15, 2000; Emails from John W. Anderson and Allison Andrews, July 7, 2017; The Medford Historical Society Photograph Collection, the Medford Historical Society & Museum, Medford, Mass.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.