By Miranda Dean

Along the rocky slopes west of Gettysburg, Benjamin Asbury Campbell drew his last breathe on July 3, 1863.

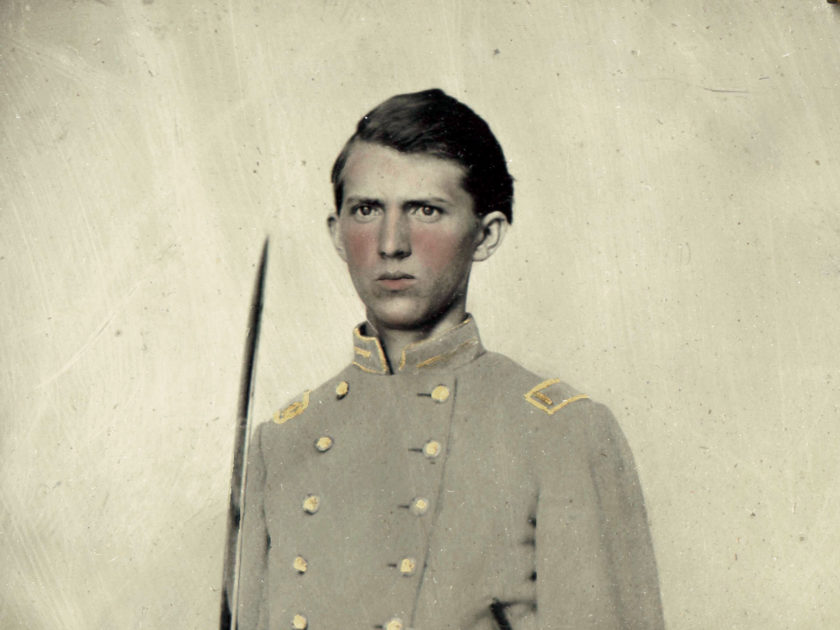

The 21-year-old Texan, a dashing figure with cascading, honey-blond curls, was the beau ideal of a Southern soldier. It therefore seems altogether fitting that he gave his last full measure on one of the most hallowed battlegrounds on American soil.

Born in Alabama, Campbell barely knew his father, who died early. His mother and older brother, George, raised him. In 1852, his mother remarried and the family moved to Anderson County in East Texas. In this farming community, the boys matured and became inseparable for a time. They oversaw the farming, caught fish in the generous local waters and explored their sunny corner of the world.

During the boys’ adolescence, the question of their education interrupted their idyllic boyhoods. Ultimately, the boys were educated at different schools in Texas: Campbell in Larissa, his brother in Lebanon.

Campbell’s quick intelligence and wide-eyed idealism made him a favorite among his professors. He hungered for recognition and the opportunity to rise above his station in life. He was pleased when a geology professor invited him on a tour of the western part of the state. Campbell spent the trip making notes, and examining rivers and ridges and basins with a keen fascination. He was thrilled to learn about the diversity of natural phenomena in his home state.

At some point during his impressionable teen years, Campbell fell in love with Eppinina Micheaux, a Kentucky belle from a prominent family that had moved to the county and established a church. When he asked Eppie to marry him, both were barely young adults. They wed in May 1860. He was 18 and she, 17.

By all accounts, Campbell doted on Eppie, who soon became pregnant. In the summer of 1861, a month after she gave birth to a baby boy, Campbell was roused by the bugler’s call.

In June 1861, he joined Company G of the 1st Texas Infantry. Though prominent family connections and privileged education had enabled him to enlist as a second lieutenant, his vigor and leadership abilities earned him a promotion to first lieutenant.

The year proved a dizzying confluence of events for the young officer. Campbell spent the first several weeks of his military career drilling at Long Lake in Anderson County, learning brute physical maneuvers that had little to do with lofty Southern ideals. Officers and men drilled in uniforms sewn by local women on a volunteer basis, and subsisted on provisions that were a far cry from the lush dinners of home. Campbell’s darkest hour arrived in August, when a letter informed him that his infant son was dead. His grief and homesickness was strong, but not enough to erode his belief in the Confederate cause.

That same month, Campbell and his comrades in the 1st assembled in Richmond, Va., joining the 4th and 5th Texas infantries and the 18th Georgia Infantry to form the Texas Brigade. The regiments were under the command of Brig. Gen. Lewis T. Wigfall. He resigned in early 1862, however, to join the Confederate Congress. John Bell Hood subsequently assumed command of the Confederate Senate. Gen. John Bell Hood replaced him.

Campbell wrote dutifully to Eppie and his brother during these early months. Like so many restless young men in uniform, he ached for battle.

His baptism under fire arrived during the spring campaigns of 1862, which left a corpse-ridden wake across battlefields in Virginia and Maryland. Campbell emerged unharmed from the Battle of Eltham’s Landing, the Seven Days’ Battles, Second Manassas and Antietam. Meanwhile, the long list of casualties in the 1st earned it the grim nickname “Ragged Old First.”

In October 1862, Campbell was detached on recruiting duty, and enjoyed a triumphant return to Eppie in Anderson County. Through the harvest season, his slaves (he owned 20 according to the 1860 federal census) shunted themselves along the cotton rows while he gathered fresh recruits. He attacked his duties with alacrity, and remained in the county long enough to enjoy a festive Christmas with Eppie. By January 1863, the time had come to rejoin his military unit.

Seven months later, Ben and his battle-hardened Texans arrived in Gettysburg. On July 2, 1863, at 9 a.m., the Texas Brigade stepped wearily up to Cemetery Ridge. Ben looked out over quilted pastures to the Union forces gathered along a ridge opposite its position.

“As he led his men forward, Campbell was shot through the heart and killed, his body dashed against granite formations.”

After a firefight that lasted several hours, the Texas men scrambled through low ground that came to be known as the Valley of Death. They continued onward towards Houck’s Ridge and Devil’s Den, a loose collection of igneous rock boulders that Ben might have recognized from his adolescent studies. At some point, Ben was ordered with his company to cover a gap in the lines between his regiment and the 3rd Arkansas Infantry. While leading his company forward, Ben was shot through the heart and killed, his body dashed against rocks forged in magma, rocks that had been there for eons and that would continue to be there for eons to come, rocks that stood indifferent to his cause and golden curls. His remains were never recovered.

The news reached Eppie and George soon after. Shocked and grief-stricken, they dutifully set about paying Campbell’s debts and divided his estate according to a will he had hastily written.

Eppie lived a long life, dying in 1930 without ever having remarried. George, who had enlisted in the 14th Texas Cavalry in 1861, fought on to finish the bloody war for which his little brother had given his life. The Confederate surrender hit George hard, and he returned from the war to find Southern life no longer an enchantment. Still, he established a farm and raised his family during the chaos and bitterness of Reconstruction.

As Campbell’s memory receded into the background of the family’s consciousness, George added a passage to the family Bible. “Benjamin Asbury Campbell,” he wrote, “departed this life fighting for liberty.”

Miranda Dean is a writer living in Columbus, Ohio. She has previously contributed to the Woonsocket Callin Rhode Island and is currently working on her first novel.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.