By Ronald S. Coddington

The Confederate raider Alabama presented an extraordinary sight as she steamed the Caribbean Sea towards the island of Jamaica in late January 1863—a portion of her sleek top deck had been transformed into an outdoor hospital ward.

Sick and wounded men breathed fresh ocean air from comfortable cots protected from the scorching rays of the sun by temporary canvas sheets. All aboard were ordered to keep noise to a minimum, as not to disturb the patients.

Perhaps the most unusual aspect of the deck arrangement was that the patients were Union prisoners of war. Though many were too ill to move, their Confederate captors kept a keen eye on them.

The makeshift hospital had resulted from the efforts by one prisoner, Surgeon Edward Sylvester Matthews. Until recently, Matthews and his fellow captives had served on the Union warship Hatteras, an iron-hulled, side-wheel steamer. The ship and crew had wracked up a number of blockade-runner captures along the Florida and Gulf coasts.

The Pennsylvania-born Matthews had offered his services to the navy soon after the war began. An 1860 graduate of Columbian College in Washington, D.C., he received an appointment as an assistant surgeon in July 1861, and was assigned to the crew of the Hatteras for duty in the West Gulf Blockade Squadron. He had the good fortune to serve with two of the navy’s top commanders. George “Pop” Emmons, an explorer, author and seasoned veteran, captured or destroyed 46 enemy ships and blockade-runners during the war. After he left the Hatteras in November 1862, his replacement was Lt. Cmdr. Homer C. Blake. A gallant, 40-year-old career officer, Blake was old enough to be the father of Matthews and many of the 125 junior officers and crew on board.

A few months after Blake assumed command, the Hatteras joined an armada assembled off the Texas coast on Jan. 6, 1863. Rear Adm. David Farragut led the flotilla in an operation to capture the port of Galveston. Five days earlier, on New Year’s Day, the city fell after rebel forces subdued the federal garrison.

The Hatteras lay at anchor with the fleet outside Galveston on the afternoon of January 11, when a signal arrived from the flagship Brooklyn. An unknown sail had been spotted on the horizon, and the Hatteras was ordered to give chase.

Lt. Cmdr. Blake reacted. “I got underway immediately and steamed with all speed in the direction indicated,” he stated in his after-action report. “I continued the chase and rapidly gained upon the suspicious vessel. Knowing the slow rate of speed of the Hatteras, I at once suspected that deception was being practiced, and hence ordered the ship to be cleared for action with everything in readiness for a determined attack and vigorous defense.”

Officers and sailors scrambled into position. Matthews may have taken his place below decks in the sick bay.

“When within about 4 miles of the vessel, I observed that she had ceased to steam and was lying broadside on, awaiting us,” Blake continued. “It was nearly 7 o’clock and quite dark, but notwithstanding the obscurity of the night I felt assured from the general character of the vessel and her maneuvering, that I should soon encounter the rebel steamer Alabama.”

Blake was correct. The Alabama and her wily commander, Raphael Semmes, were a legend. The Maryland-born captain drew the Hatteras into the open sea, confident of victory.

Outgunned, outmanned and outmaneuvered, Blake brought the Hatteras in close and searched for an opportunity to board the Alabama and capture her crew. “I came within easy speaking range, about 75 yards, and upon asking ‘What steamer is that?’ received the answer, ‘Her Britannic Majesty’s ship Vixen.’ I replied that I would send a boat aboard, and immediately gave the order. In the meantime both vessels were changing their positions, the stranger endeavoring to gain a desirable position for a raking fire. Almost simultaneously with the piping away of the boat the strange craft again replied, ‘We are the Confederate steamer Alabama,’ which was accompanied by a broadside.”

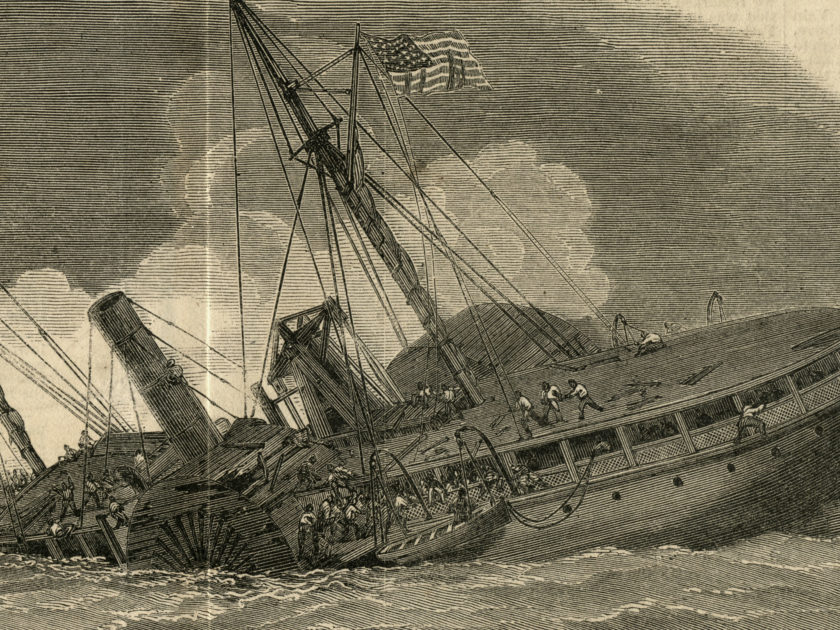

The Hatteras returned fire and closed to within 30 yards. Musket and pistol shots mixed with cannon fire from both vessels. Suddenly, the gunners of the Alabama struck with deadly accuracy: One shell tore into the Hatteras amid ship and set fire to the hold. Almost simultaneously, a second shell ripped through the sick bay, concussing Matthews, and exploding in an adjacent room, setting it ablaze. A third shell mortally wounded the Hatteras when it struck and disabled her engine cylinder. Deprived of power to maneuver or operate pumps, the Hatteras sat effectively dead in the water.

Still, Blake fought on. “With the vessel on fire in two places, and beyond human power a hopeless wreck upon the water,” he explained. “I still maintained an active fire, with a double hope of disabling the Alabama and of attracting the attention of the fleet off Galveston, which was only 25 miles distant.”

At this point, Blake learned that more shells had struck the Hatteras below the waterline, and that the ship was rapidly taking on water.

On board the Alabama, Semmes signaled with an offer to assist the doomed crew. Blake accepted, and noted, “I felt that I had no right to sacrifice uselessly, and without any desirable result, the lives of all under my command.”

The crew of the Hatteras was rescued, including Matthews. Two of their number, both African-American sailors, were lost with the ship.

Southerners reacted with jubilation when they received news of the Alabama’s victory. The Hatteras was sent “where Semmes loves to send Yankee ships, and where there is ample anchorage for more of them,” the Charleston Daily Courier boasted.

Northerners made the best of a tough loss. The New York Herald noted, “The gallant little Hatteras died game, and showed her pluck to the last. For twenty minutes she sustained and returned the raking fire of her huge antagonist, and at last went down, under the gallant Blake, with her guns still speaking and the old flag flying from the peak.”

Meanwhile, Semmes and the Alabama steamed toward the Jamaican port of Kingston. According to interviews conducted by the Herald, “Semmes minutely superintended everything in connection with the movements of the prisoners himself, and our gallant officers and soldiers found themselves for the first time in their lives, treading the decks of a real pirate ship as prisoners, and that ship manned by their own countrymen in arms against the flag which had proudly waved from mastheads in every part of the civilized globe. They looked aloft and saw the rebel emblem flying, when the sailor’s heart, which is always open to the tenderest emotions of patriotic ardor, beat high with indignation at the thoughts that he was compelled to live, for the time being, under the bastard rag of a bastard confederacy.”

The Herald added, “With regard to the treatment which they received during their entire stay on board the Alabama, the officers and men of the Hatteras, without an exception, speak in terms of eulogy. Every comfort was provided for them, and the strictest attention paid to their every little want.”

Matthews must have been particularly pleased. His suggestions for the care of the wounded, which numbered five, and the sick were adopted. He also had ample medicine available from the Alabama’s well-stocked supplies.

Semmes paroled the Hatteras crew at Kingston, and continued to raid Union vessels for more than a year. The Alabama’s reign on the high seas came to an end on June 19, 1864, when the sloop-of-war Kearsarge sunk her off the coast of Cherbourg, France.

Blake, Matthews and their shipmates checked in with the U.S. consul before journeying home via Key West, Fla. They arrived in New York City on Feb. 25, 1863, and obeyed their paroles until formally exchanged.

Blake went on to distinguish himself in military operations along the James River in Virginia, and remained in the navy after the end of the war. He died in 1880 on active duty with the rank of commodore.

Matthews suffered chronic neuralgia from the concussion he received in the fight with the Alabama. But, he continued in the service. In December 1864, he was assigned to the sloop-of-war San Jacinto. During the pre-dawn hours of New Year’s Day 1865, near the Bahamian island of Great Abaco, the vessel wrecked on a reef off Green Turtle Cay—an experience that exacerbated his neuralgia.

Navy authorities granted Matthews a leave. He went to Providence, R.I., where he married Mary Elliott, whom he had met shortly before he joined the San Jacinto. Soon after the wedding, he received orders to report to Key West. While there, he suffered from bouts with yellow fever and malaria, which further weakened his precarious health.

Matthews returned to Providence in May 1865. “He came home in charge of a nurse, and was so feeble when he arrived …” remembered Mary. “He had to be assisted upstairs, and I do not think he had good health after that; there was scarcely a day that he did not have to take some medicine to relieve himself from the neuralgic pains.”

Mary administered the medicine, morphine, in increasingly larger doses, unaware that the drug was an opiate. By the time she discovered the truth about the drug, Matthews was addicted.

“I, having read up a book upon the opium habit, commenced to try to cure him myself, and in my desire to substitute a less evil for a greater advised him to take chloroform (inhale it) in order to get relief from pain,” she added. “The effect was terrible, for the chloroform finally made him a raving maniac, and so disturbed him, and he had such a craving for it that it was dangerous to be about the house with him.”

“Semmes minutely superintended everything in connection with the movements of the prisoners himself, and our gallant officers and soldiers found themselves for the first time in their lives, treading the decks of a real pirate ship.”

Trapped in a downward spiral of narcotic dependency, marked by occasional episodes of lucidity, during which he attempted to break free from morphine, Matthews’ addiction eventually cost him his navy career. With few options left, Mary took her father’s advice and committed Matthews to an asylum. Her father accompanied Matthews on an overnight trip to a facility on Aug. 15, 1881. They stopped at a hotel, where her father stepped away for a few minutes. Matthews drifted away from the hotel, and ingested a lethal dose of morphine from a bottle that he procured or carried with him. A policeman found him against a fence, apparently ill, and offered aid. Matthews collapsed in a stupor. Transported to a hospital, he died that night at 12:35 a.m. He was about 41.

A note in his pension file attributes his death to the concussion he suffered in the fight with the Alabama.

Despite his affliction, Matthews was best remembered for his war service. A statement in his pension file praises him as “an officer of remarkable ability and skill. His bravery in action, and his heroism in the presence of danger, and his conspicuous patriotism were worthy of the high commendation which they received from his commanding officers.”

References: New York Herald, Feb. 26, 1863; Howard L. Hodgkins, Historical Catalogue of the Officers and Graduates of The Columbian University; Lewis R. Hamersly, Records of Living Officers of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies; John S.C. Abbott, “Texas Won and Lost,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (September 1866); Charleston Daily Courier, Jan. 26, 1863; New York Herald, Jan. 28, 1863; Edward S. Matthews pension record, National Archives.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI. He is the author of Faces of the Civil War Navies: An Album of Union and Confederate Sailors, a new book recently released by The Johns Hopkins University Press.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.