By Jeff McArdle, with images and letters from the author’s collection

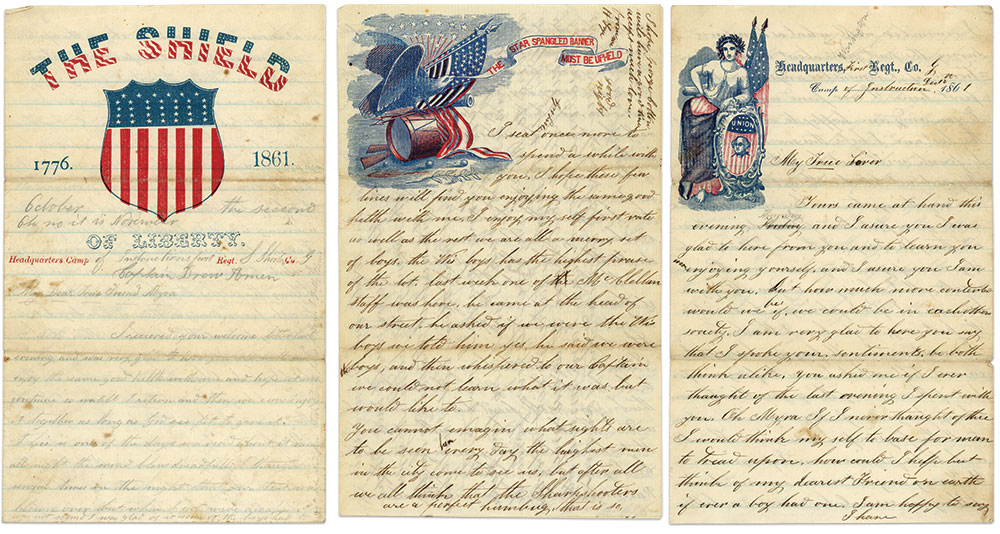

A few miles south of the Pennsylvania state line on June 30, 1863, sharpshooter Henry Lye scribbled a short note to his sweetheart. By his count, the regiment had marched 145 miles in six days seeking out the rebel invaders. With the few moments he had to himself, he managed to produce only a few lines about his good health and the kindness of Marylanders. Unsure of the enemy’s position but sensing their nearness, he continued writing until the sound of the bugle beckoned him and his comrades to assemble. “I will have to get some kind woman to mail this for me,” he signed off as the column resumed its march toward the crossroads community of Gettysburg.

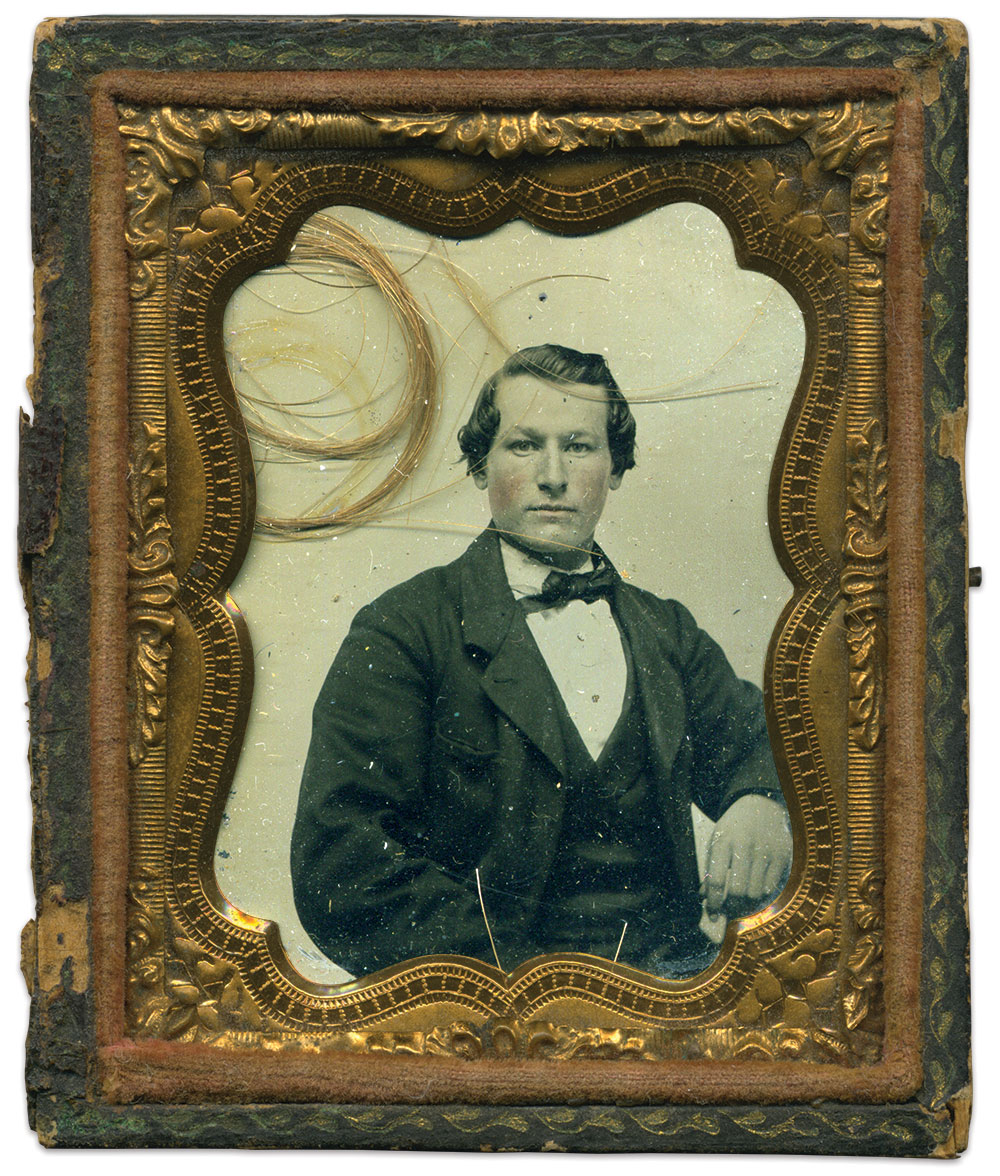

Eight hundred miles away in Middleton, Wis., Almira Sherrer awaited the letter’s arrival like she had so many times before. Henry had written regularly to Myra, as he called her affectionately, since joining the army two summers earlier. They fell in love in the months before his enlistment, but he had left so abruptly that, two years later, all Myra had were a hundred letters and a handful of photographs to remind her of her “noble, kind and true, generous, and always happy” Henry.

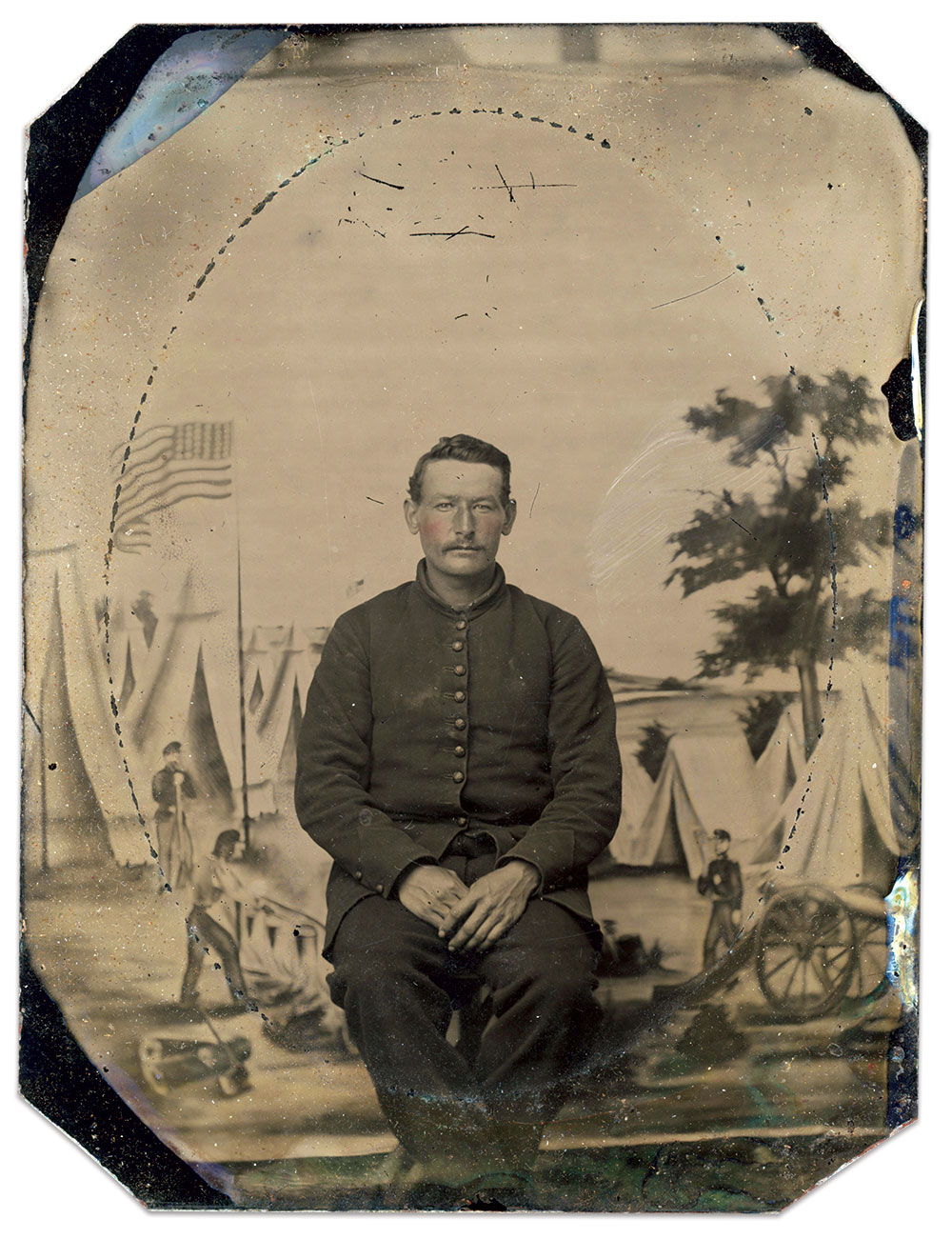

Skilled with the rifle and swept up in the energy of the secession crisis of 1861, 23-year-old English immigrant Henry Lye had enlisted in Capt. William P. Alexander’s company of Wisconsin marksmen. Bound for Washington, D.C., the unit was soon designated Company G in Col. Hiram Berdan’s 1st United States Sharpshooters. After his arrival at the regiment’s camp of instruction, Henry and Myra began their regular correspondence. Through his words, she would have imagined Henry struggling to scribble a letter in his tent. “I am sitting on my knapsack with a board on my knees and writing to one who I think more of than I do of my own life,” he wrote in October. Jostled by the other men, he added, “It is pretty hard for to write here. There is so many boys coming in and out.”

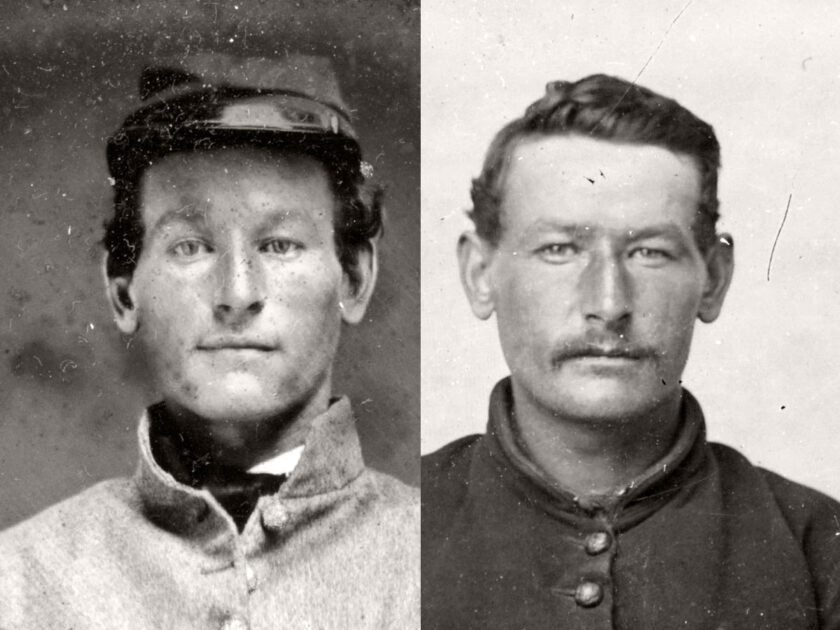

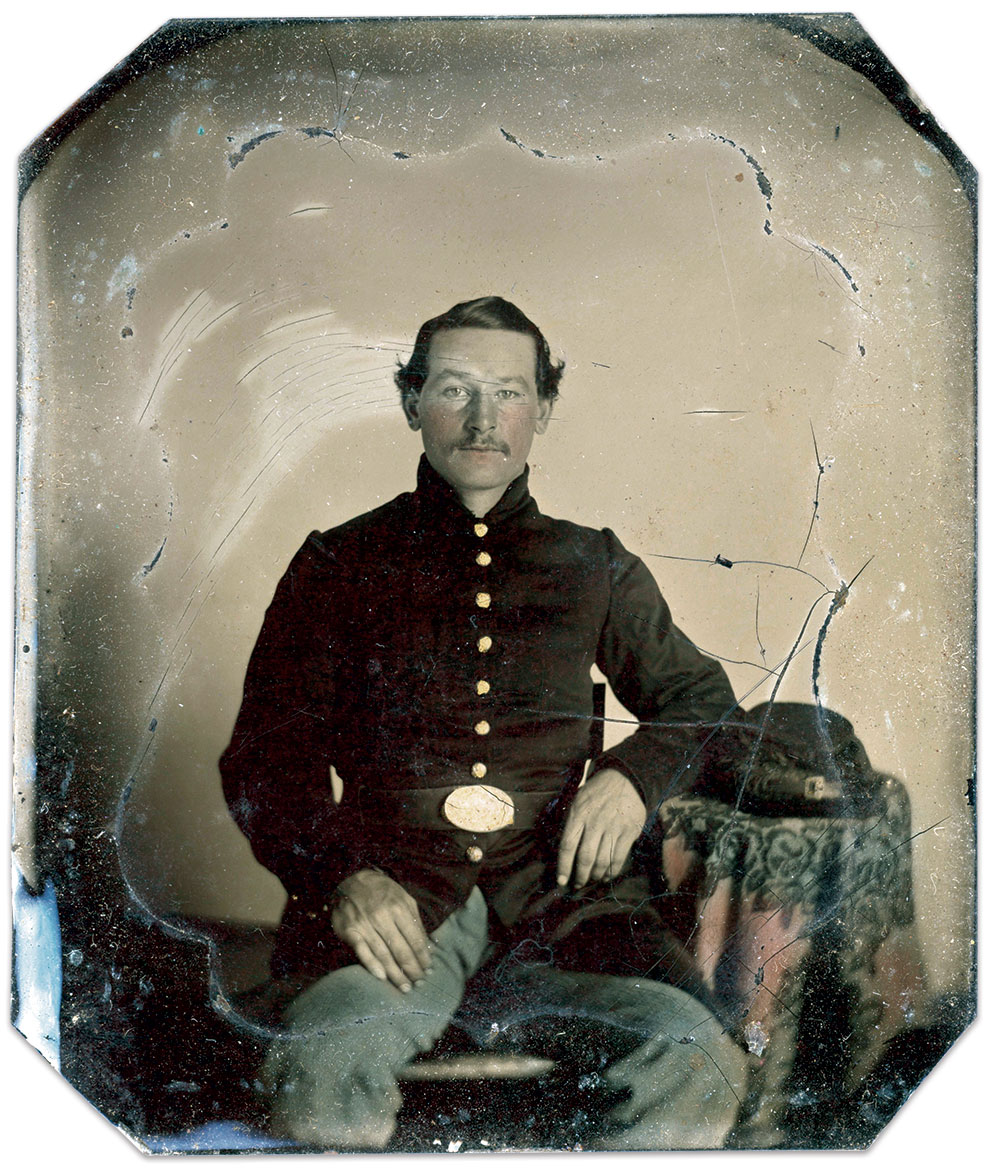

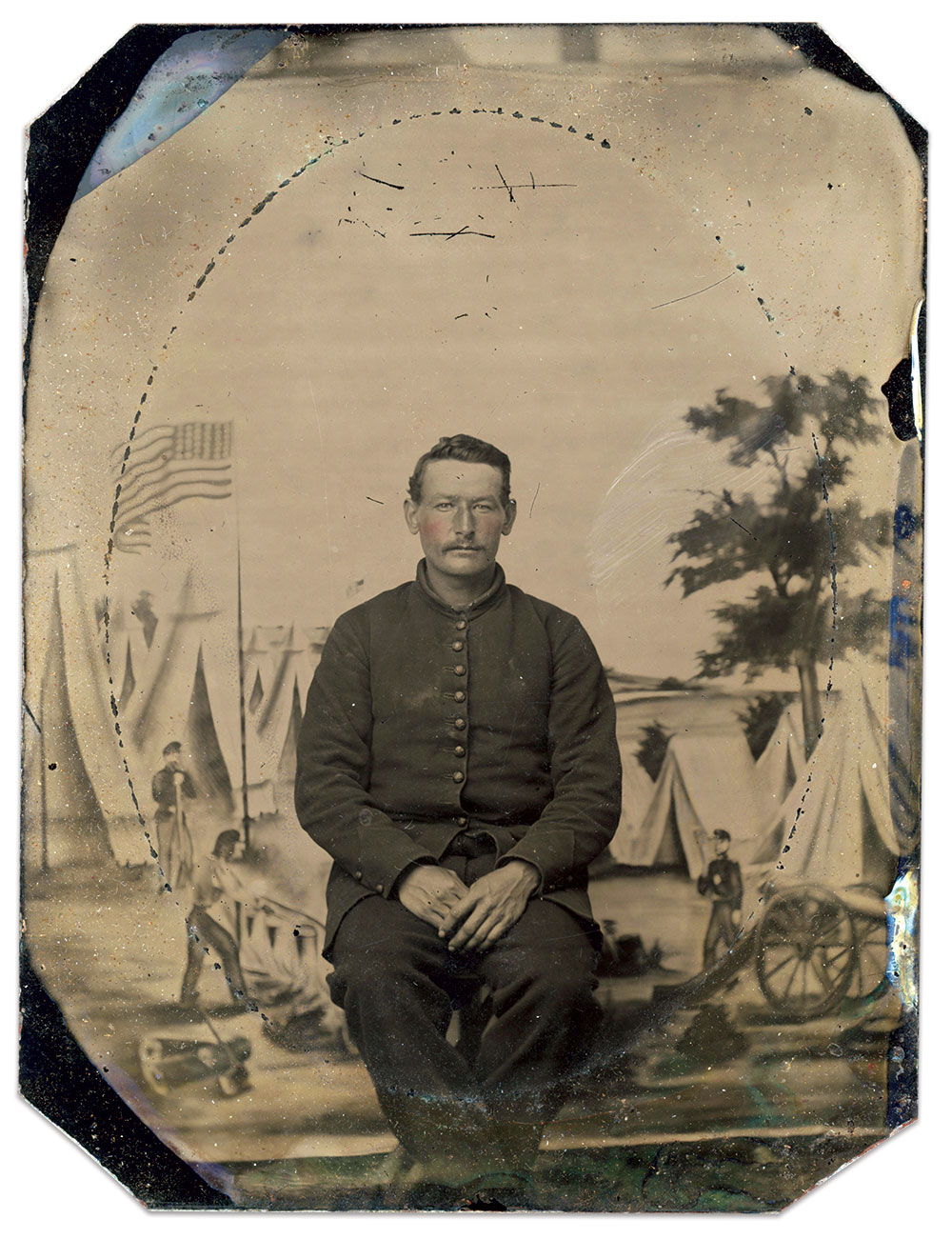

Seven photographs of Henry, particularly four made in a 20-month period between September 1861 and April 1863, demonstrate how the rigors of war transformed a jaunty young volunteer into a worn-down veteran. Wearing a gray frock similar to those worn by early members of the 2nd Wisconsin, a smirking Henry poses in the earliest image, a sixth-plate ambrotype. In contrast, Henry gives no hint of a smile in an April 1863 quarter-plate tintype. With one eye slightly squinted, he looks as if he’s about to take aim down the barrel of a Sharps rifle. He appears to have aged years instead of months. On the other hand, how could any man remain unchanged after fighting in a dozen battles and skirmishes, facing nearly constant danger for days and weeks at a time, as Henry did?

We know from his letters that Henry’s experience was like that of most soldiers. Periods of training and boredom during the cold-weather months were followed by footsore marches on campaign, punctuated by the peril and misery of battle. His thoughts were often of Myra. “There is not an hour during the day but what I think of thee,” he wrote from Washington in March 1862. From Harrison’s Landing, Va., in August 1862, he hoped for their future together, writing, “You are my nearest friend on this earth and there is scarce an hour that pass over my head but what I think of you. And I know you do of me. Yes Myra, I promise you that I will come as soon as I can after Peace is declared if God will spare my life, and I pray that he may.”

Henry anxiously awaited each mail call for word from Myra. Only two of her letters survive. In one, written in December 1861, she recalled their last too-brief meeting before he left for the war:

I have often wished since that we had talked longer…. I have often thought with regret that perhaps it was the last time I would have an opportunity to refuse you. I am sorry a hundred times over that I did not grant as small a favor as that…. You know you enlisted so sudden and my mind was on your going away, and thought perhaps I would never see what I trust you are, my best Friend, again.

Henry’s accounts often include lighter moments. In another letter from Harrison’s Landing, he explained a creative way for disposing of pests. “The flies are very thick and we amuse ourselves by spreading sugar and gun powder, and when there is a lot collected together we put a slow match to it. And then where Mr. Flys was, they wasn’t.” In another incident from Washington, he described how Pvt. Amos Sumner fired a pistol in their tent. “He has the muzzle about three feet from a piece of paper for a marker. Oh, what a smell of gun powder. Well, we cannot say we did not smell powder,” he jokes. “He has hit the marker four times out of five—pretty well done. Our tent is full of smoke.”

The Sharpshooters, however, would be remembered for more than trick pistol shots.

On the Virginia Peninsula: Coming to Terms with Killing, Morality, and War

Recognized by most as the Yankees in green uniforms, members of both the 1st and 2nd Sharpshooters were crack shots. They gained a reputation in the field for deadly accuracy with their Sharps Model 1859 breechloading rifles, sniping unsuspecting rebel pickets, artillerymen, and officers often from distances of up to a thousand yards. Major Gen. Fitz John Porter, in whose corps the Sharpshooters served during the Peninsula Campaign of 1862, praised the regiment in official reports, noting that at Yorktown they “did good service in picking off the enemy’s skirmishers and artillerists whenever they should show themselves.” Henry himself commented in a letter from Yorktown that “when any of the Generals go out to take a view of the fortifications, some of the Sharpshooters go with them as a bodyguard,” adding that the unit “has a big name through the whole army.”

Not all opinions were positive. Second Lt. David F. Ritchie of the 1st New York Light Artillery’s Battery A remarked during the Yorktown siege that although the Sharpshooters had “become a terror to the enemy,” he felt “this lying in wait and picking off men singly is after all a barbarous method of warfare and has very little to do with the shortening of the rebellion.” Francis A. Donaldson, a sergeant in the 71st Pennsylvania Infantry, was even more open with his view in an April 1862 letter to his brother. “These men speak confidently of killing, without the slightest difficulty, at a mile distant,” Donaldson wrote of the Sharpshooters at Yorktown. He then recounted how “four of these demons” simultaneously picked off three rebel soldiers, and then also shot four stretcher bearers sent to retrieve them:

I can scarcely bring my pencil to write it, but these inhuman fiends, these vaunted brave Berdan sharp shooters, murdered these poor fellows also. I will add that there was a good deal of feeling displayed by my men, and Mr. Rifleman was requested to go somewhere else, as their presence was distasteful.

To many of the citizen-soldiers who had been farmers, students, laborers, and clerks in their hometowns only months before, such acts must have seemed disgracefully immoral.

Henry’s letters to Myra, unsurprisingly, contain few details that might bring dishonor to himself or the regiment. Still, his own feelings about war’s violence shifted dramatically over the course of a year. In his first action in March 1862, for example, he joyfully related how the Sharpshooters chased enemy scouts out of Big Bethel, Va., causing one rebel to collapse from exhaustion. Henry coolly states that when the man refused to surrender, “a little bugler shot him through the head,” before remarking pleasantly that “it is fun to be at the head of the column, for you can see all that is to be seen and hear what the Generals and Officers has to say on the subject.”

By April 1863, however, he expressed different sentiments over his role in the ongoing violence. On the eve of the Battle

of Chancellorsville, evidently in reply to a request from home, he wrote:

Please tell Mr. W. I will not promise to shoot a rebel for him. I do not wish to take the life of any man. Neither do I want to know that I ever have. It is true we came here for that purpose, and when I am in action I will try and do my duty. Men at home and men in the field do not think alike in this respect. There is not one man in a thousand who can say he shot a rebel and speak the truth. I know of one or two who shot one but I am certain he could have taken him prisoner, and is it right to take a man’s life so? I think not, and I will never shoot a man when I can take him otherwise.

After a year of heavy campaigning, Henry still hadn’t lost his sense of humanity. Or at least that’s what he wrote to Myra.

The Wisconsin company spent five weeks on the line at Yorktown. In each of the 10 letters written here, Henry described the nearly constant threat from enemy artillery and sharpshooters.

On April 5: “Several of our boys had a close call. One was struck in his cheek with a piece of a shell, while another piece went through the tin on his knapsack.”

On April 11: “You may think it’s strange, but while we were there, [with] shells and minnie balls flying around us in every direction, and some getting killed and wounded, we were laughing all the time. We could not help it, for they made such a queer noise.”

On April 12: “There go the shells. I do not want them to come near me. If they will keep their distance is all I ask…. Two in Co. C was slightly wounded—one in his finger and Old California [Joe]’s gun was struck with a ball, and a piece glanced and struck his cheek and nose. Neither of them will have to be off duty. Hurrah for our side.”

And on April 30: “They are not contented enough by shelling us during the day, but they fire at intervals all night, keeping us from sleep, and they make a tremendous rattling through the woods in the still of the night. It is ten times as bad as heavy thunder. I can hear the roar of the cannons and the bursting of the shells while I am writing.”

Two companies of the Bucktails were taken prisoners from the same rifle pit we were in, but we—all our Company, excepting one of our boys—made our escape good. Lucky for us.

Six weeks later, with the Army of the Potomac near enough to Richmond to hear the bells of the city’s churches, Henry faced the maelstrom of the Seven Days battles. In attack after deadly attack, Confederate forces drove the federals away from their capital. At Beaver Dam Creek on June 26: “Two companies of the Bucktails were taken prisoners from the same rifle pit we were in, but we—all our Company, excepting one of our boys—made our escape good. Lucky for us.”

The next day, June 27, at Gaines’ Mill: “We held our ground, but the loss was heavy on both sides,” after which the army “took up a line of march towards the James River.”

And at Glendale on June 30, Henry “had to run the risk of my life” to capture a rebel lieutenant colonel and make a trophy of his fine revolver, which he sent home to Middleton. It was also at Glendale that the company’s popular Capt. Edward Drew tragically fell: “We were overtaken by the rebels and had a very hard fight. This is where we lost our Captain and the rest of the boys, but we held our ground and they were driven back with a heavy loss.”

The retreat continued to Malvern Hill. Upon observing the ferocity of the rebel attacks there on July 1, Henry concluded, “the rebels have whiskey and gun powder in their canteens enough to make them fight.” Defeated and demoralized by mid-July, he reported the regiment could muster only one hundred fifty men when they regrouped at Harrison’s Landing on the James.

The year was only half over. New dangers were to be met in August as the Confederates moved into northern Virginia. “What would I give to go home and never to come soldiering again, for I have seen enough of fighting and the horrors of war,” he wrote after the carnage of Second Bull Run. “The sights I have seen and the many brave men I have seen fall is enough to make a man break a heart. Oh, it is dreadful.”

After surviving another fight September 20 at Shepherdstown Ford, he wrote, “I do not think my mother would have known me…for I had a shirt on which I wore without changing 21 days, and scarcely any shoes, and the peak of my cap was half torn off, and about worn out myself. Who would not be after marching over 150 miles without scarcely any rest and in a big fight besides? I wish this war was over and I was safe Home.”

Chancellorsville and Gettysburg: The Long Last March

The encampment at Falmouth, Va., that winter offered an opportunity to rest and refit. Bolstered by the return of men who had been sick or wounded in the previous months, the Wisconsin company prepared for a new campaign. This is the Henry Lye we see in the 1863 tintype. The man is clearly changed by the experiences of the preceding year. He is prepared to do his duty, but also ready to go home.

Only days after sitting for the tintype came the disastrous defeat at Chancellorsville, “one of the hardest battles yet.” When the Union’s 11th Corps “came running back like stuttering sheep” after being attacked on their flank, Henry described how it left his own 3rd Corps surrounded, “but they fought their way out.” In the confusion, he became separated from his company, narrowly escaping to the lines of the 12th Corps. “If I had gone ten rods the wrong way I would have been taken prisoner.”

Through letters written in May and June, Myra could follow the company’s long march toward Gettysburg. Using his rifle for a desk, he wrote June 16 from Bull Run, “I am still well and hope to be able to reach our journey’s end in safety, but we have had some very hard marches. Quite a large number was [down with] sun stroke yesterday…and water is very scarce.”

On June 22 from Gum Springs, Va., he lamented, “You have no idea how many poor fellows has left this world since we commenced our retreat [from the Rappahannock line]. Over one hundred in our division has either died or will never be fit for duty.” He expected that by the next night “we will be many a mile from here.”

The June 30 letter written near the Pennsylvania line was the last Myra received from Henry. Later, word arrived from Sgt. Willard Isham confirming the news Myra had no doubt already heard. Henry had been mortally wounded July 2 at Gettysburg. “Being a friend to your lost Henry,” wrote Isham, “and the one that caught him as he received the fatal ball, I thought it not out of my place to send you a few words concerning his death.” Isham was “about two paces to the right of Hank when he was hit” that afternoon, west of the Company G monument that exists today along the Emmitsburg Road. “I screamed for help and Levi Ingolsbe came,” and the two carried Henry to stretcher bearers before returning to the line. “He parted this life on the morning of 4th ins. and now sleeps the sleep that knows no wake,” wrote Isham. “May peace be with him and heaven his destination.”

Henry’s remains lie today in Gettysburg National Cemetery—a fitting resting place for a patriot who gave his last full measure for his adopted country.

Broken Hearts and Ruined Dreams

But what about the other casualties of war? The broken hearts and ruined dreams? Surely Myra observed the change in her Henry. Did she notice the change in herself? A postwar carte de visite shows a young woman also affected by the war. While she eventually married Nathan Reynolds, who had also served, the bitter sorrow caused by Henry’s loss evidently didn’t heal. In an unmailed 1872 letter to Henry’s mother, Myra expressed her ongoing grief:

I have thought more of him and about him for the last six months than before since the first year of his death. It is now nearly eleven years since he bade me “Goodbye,” and he is as fresh in my memory now as the day he left Madison for that cruel cruel war. I have been reading over his letters he wrote me while away. Oh, Mrs. Lye, he was so noble, kind, and true, generous, and always happy. I believe he rests in Heaven, and now, for the hopes of meeting him there would I consecrate my life to God. I want you to pray for me and I will for you, if you are living. I know not as this will ever reach you. But if it should, let us try to so live that we may meet Henry in Heaven, for I believe we shall know each other there. How many hardships he endured for nearly three long years, and when his time was almost out he had to die, so far from Home and kind friends. How cruel. But we are not the only ones mourn the loss of Sons & Lovers. There is hardly a home but what has a vacant chair.

References: Donaldson, Inside the Army of the Potomac: The Civil War Experience of Captain Francis Adams Donaldson; Marcot, Civil War Chief of Sharpshooters Hiram Berdan: Military Commander and Firearms Inventor; Porter, “Report of Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter, U.S. Army, commanding division, of operations April 4-6,” The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. 11, Pt. 1; Ritchie, Four Years in the First New York Light Artillery: The Papers of David F. Ritchie; Stevens, Berdan’s United States Sharpshooters in the Army of the Potomac 1861-1865.

Special thanks to Brian White and Brian Stewart for their assistance in the development of this article.

Jeff McArdle publishes scholarly journals at the University of Illinois Press. He is also owner of Iron Horse Military Antiques, where he specializes in Civil War soldier letters and images.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.