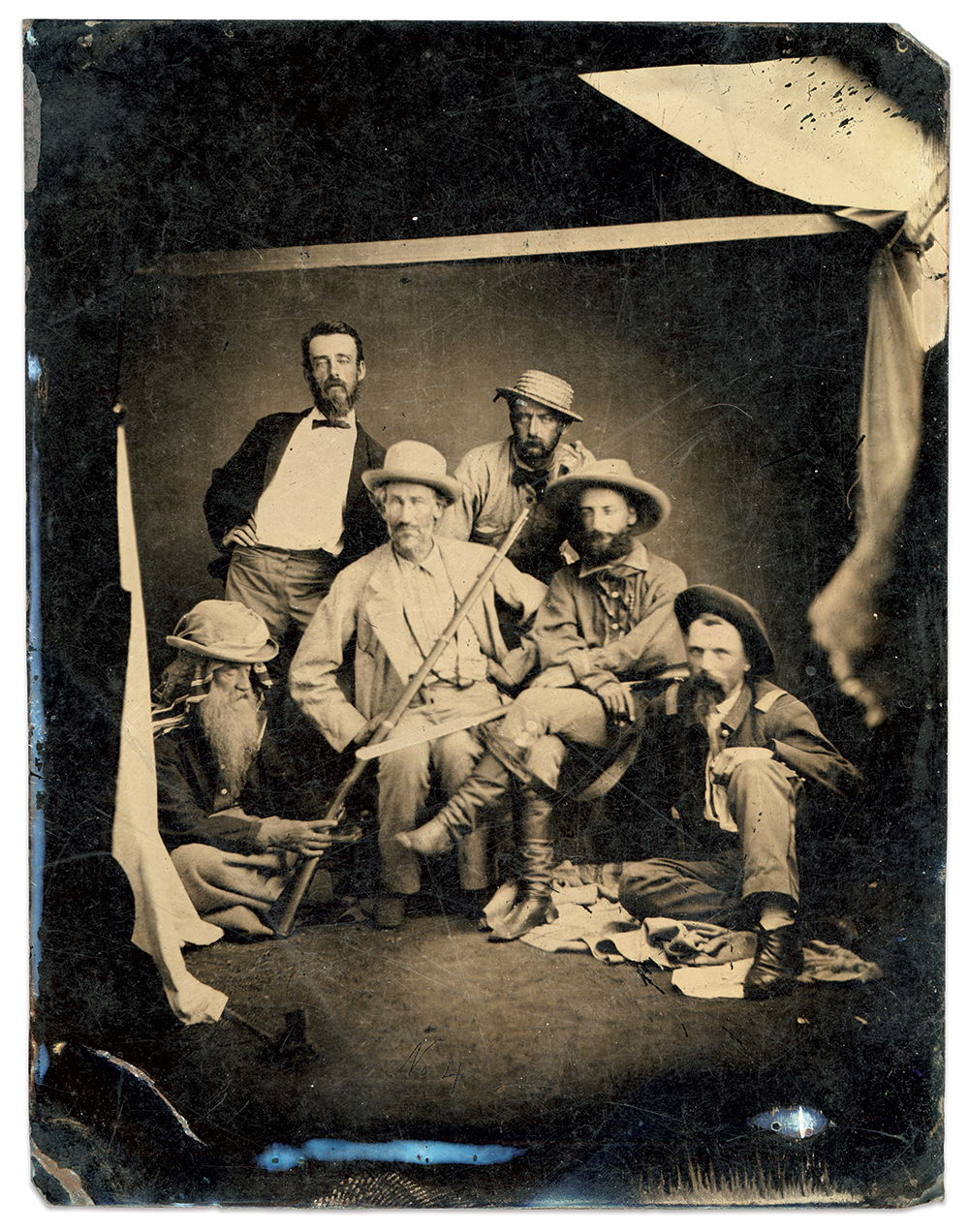

By Ronald S. Coddington, with images from The William Griffin Family Collection

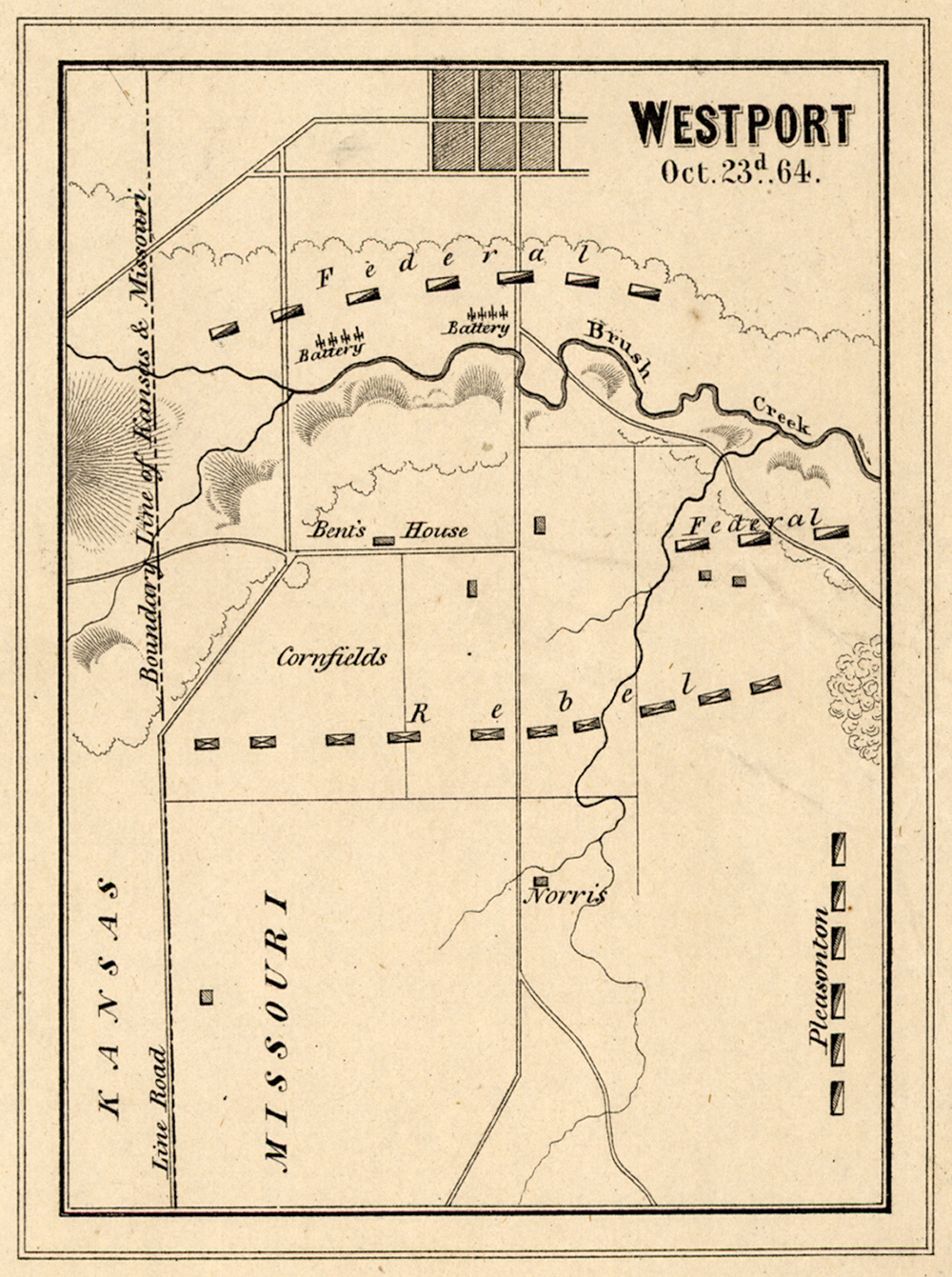

As darkness yielded to the pale glow of light on the frosty morning of Oct. 23, 1864, Confederates arrayed along the southern outskirts of Kansas City might have noticed two specks on the roof of a dimly lit hotel. Upon closer inspection with a field glass, they could have observed a pair of figures looking back at them.

The hotel, Harris House, about four miles from Kansas City in the town of Westport, offered a commanding view of the surrounding terrain. The two men, wearing Union blue with first lieutenant’s straps on their shoulders, served on detached duty as acting U.S. Signal Corps officers. One man, Ira Quinby, had only recently been trained in the evolving science of battlefield communication—wig-wagging with flags and torches, telegraphy, and courier dispatches. He had been detailed days earlier as a temporary aide to Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis, commander of the Union’s Army of the Border. The other man, McGinly M. Neely, had, like Quinby, been similarly trained.

Quinby could not have known that he and Neely stood on the threshold of a modest yet consequential role in the largest battle fought west of the Mississippi—a clash that historians would later liken, in scope and significance, to Gettysburg.

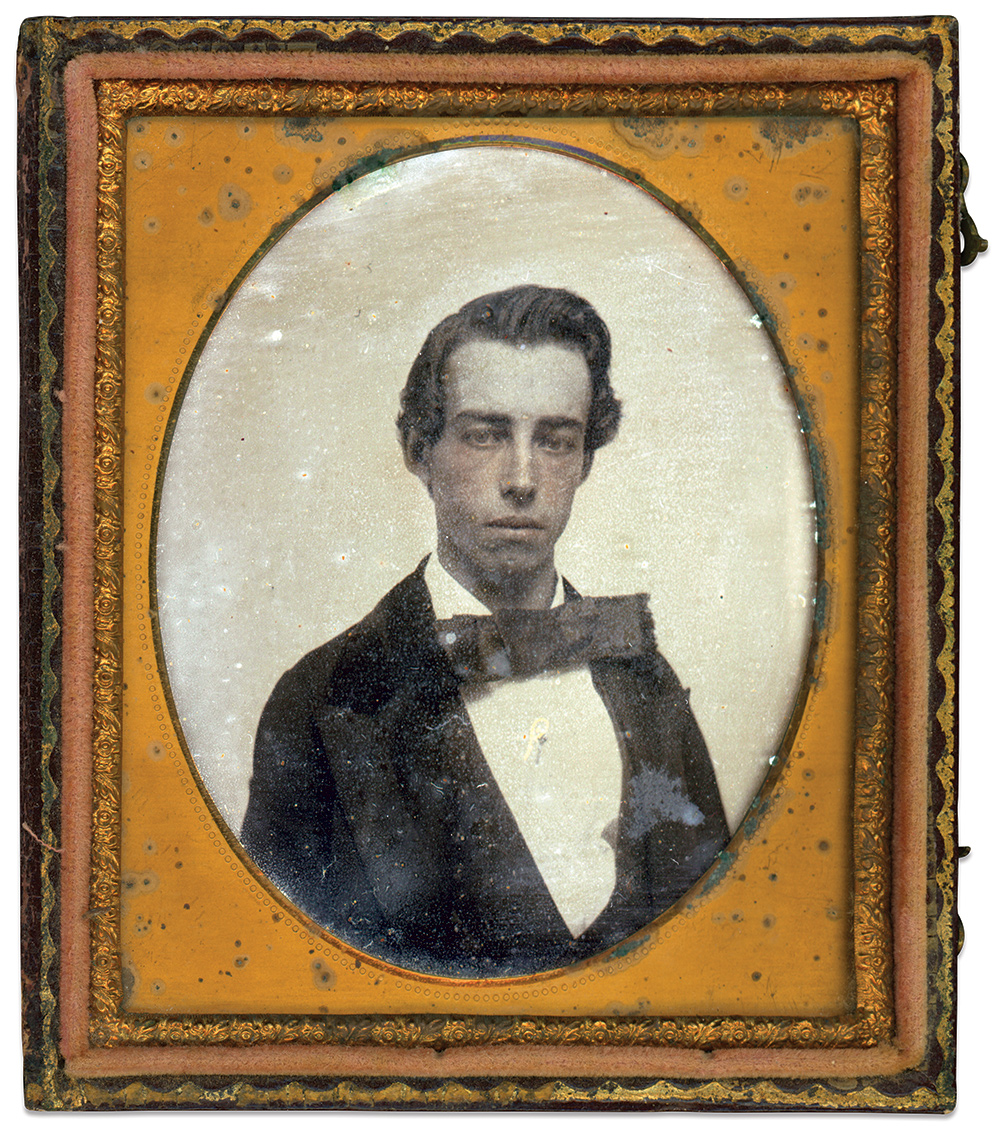

Quinby’s path to that rooftop began 29 years earlier in Otsego County, N.Y. The son of Ira, a shoemaker, and Catherine Quinby, he was the second of four children raised in the village of Morris. He attended the local school and by his teens worked on a farm, but neither agriculture or shoemaking suited him. In 1857, around age 22, he joined the great westward migration, spending a year each in Illinois and Kansas Territory. His time in Kansas overlapped with the violent struggle between pro- and anti-slavery factions battling to shape the territory’s statehood.

Then, in 1859, Quinby pushed farther west, into a rugged expanse of high country where territorial boundaries blurred. Though his exact motivations are unclear, the timing of his arrival suggests he rolled with the tide of Americans drawn by the promise of fortune and new beginnings of Pike’s Peak Gold Rush. Supporting this theory are 1860 newspaper reports mentioning him as a businessman in Golden City, known today as Golden.

The war forever altered Quinby’s path.

“A Good Soldier, and a Bully Good Boy”

In Colorado Territory, the war added the danger of Confederate invasion of and guerrilla raids on rich gold fields to a rapidly expanding frontier population that intensified friction with established Native American tribes. To confront the dual threats, the government beefed up its military presence in the region.

While some settlers returned to their home states back East to fight rebels, Quinby remained. He joined one of four independent infantry companies that formed in mid-1861. In early 1862, they became the nucleus of a new regiment, the 2nd Colorado Infantry. Quinby, as first sergeant of Company D, reported for duty with Company C to Fort Union in New Mexico Territory. They operated against Navajo warriors, as well as Confederate guerrillas, in April 1862.

Soon after, the War Department consolidated Companies C and D with the undersized 1st Colorado Infantry to form the new 1st Colorado Volunteer Cavalry. The switch to cavalry was made with the belief that troopers were better equipped to fight native warriors. Quinby advanced to second lieutenant of Company M in this reorganization at Denver’s Camp Wild.

Quinby “was a most congenial and companionable gentleman and a general favorite in whatever capacity he served.”

Quinby honed his skills over the next two years, primarily in the southeastern section of Colorado Territory at Camp Lyon, where he guarded mail routes and served stints as post adjutant and provost marshal. In May 1864, he received a promotion to first lieutenant of Company K.

Army life agreed with Quinby. His actions during this formative period in his life prompted a reaction by one correspondent: “He was a most congenial and companionable gentleman and a general favorite in whatever capacity he served.” A friend wrote with more feeling: “‘Quin’ is a good soldier, and a bully good boy.”

From Comanche Lances to Signal Flags

In the mid-1850s, as the story goes, a young assistant surgeon posted in New Mexico Territory had a flash of inspiration. Observing a group of Comanches signaling with lances to others on a distant hill, he wondered—could such visual signals be adapted for military use? Driven by the idea, and drawing on his background in art, science, and telegraphy, he became consumed with developing a system for the Army to communicate across distances.

Within a few years the surgeon, Albert J. Myer, had developed a plan that attracted the attention of the War Department in Washington, D.C., where its principles were tested by a board and furthered by experiments conducted with the blessing of Secretary of War John B. Floyd. Congressional funding followed, and, by 1860, the U.S. Signal Corps had come into existence.

During the summer of 1860, Myer, now major and Chief Signal Officer, began real-world testing in New Mexico against native tribes. The value of signaling as a communication method rapidly spread across the army as the clouds of civil war darkened the nation. Among the earliest proponents of the service was a recent West Point graduate—Horace Porter, who became a lifelong friend of Myer, and a member of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s military family.

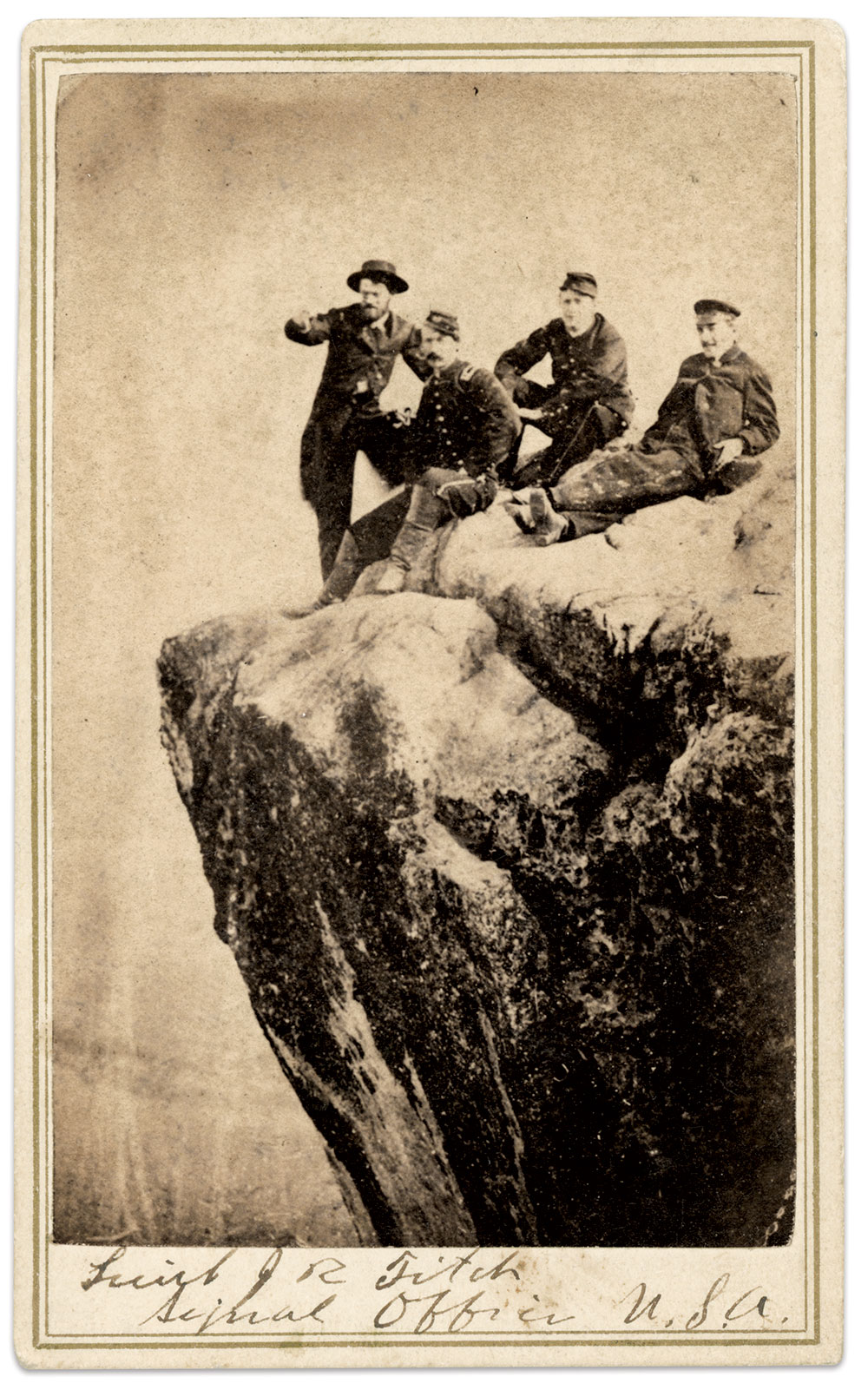

In the District of Columbia, a camp organized in Georgetown served as a hub for the new service. The Army’s insatiable appetite for signal officers, driven by the rapidly escalating war, resulted in the deployment of assets to the Eastern and Western theaters as quickly as possible. In June 1864, a detachment of 56 men left the Georgetown camp for the Department of Missouri with its headquarters at Fort Leavenworth.

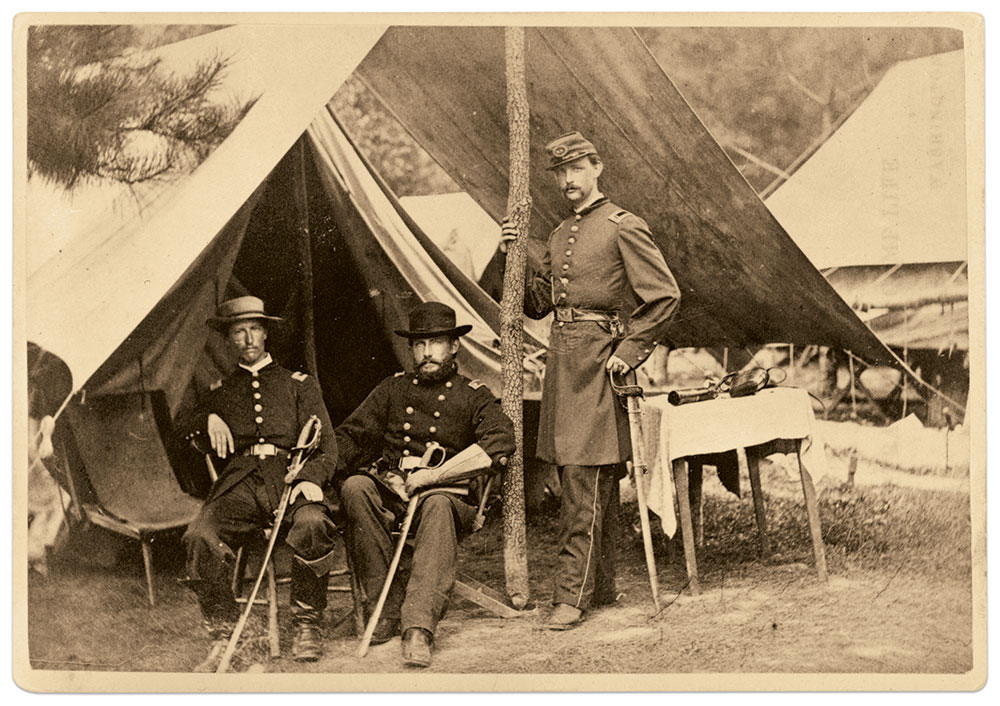

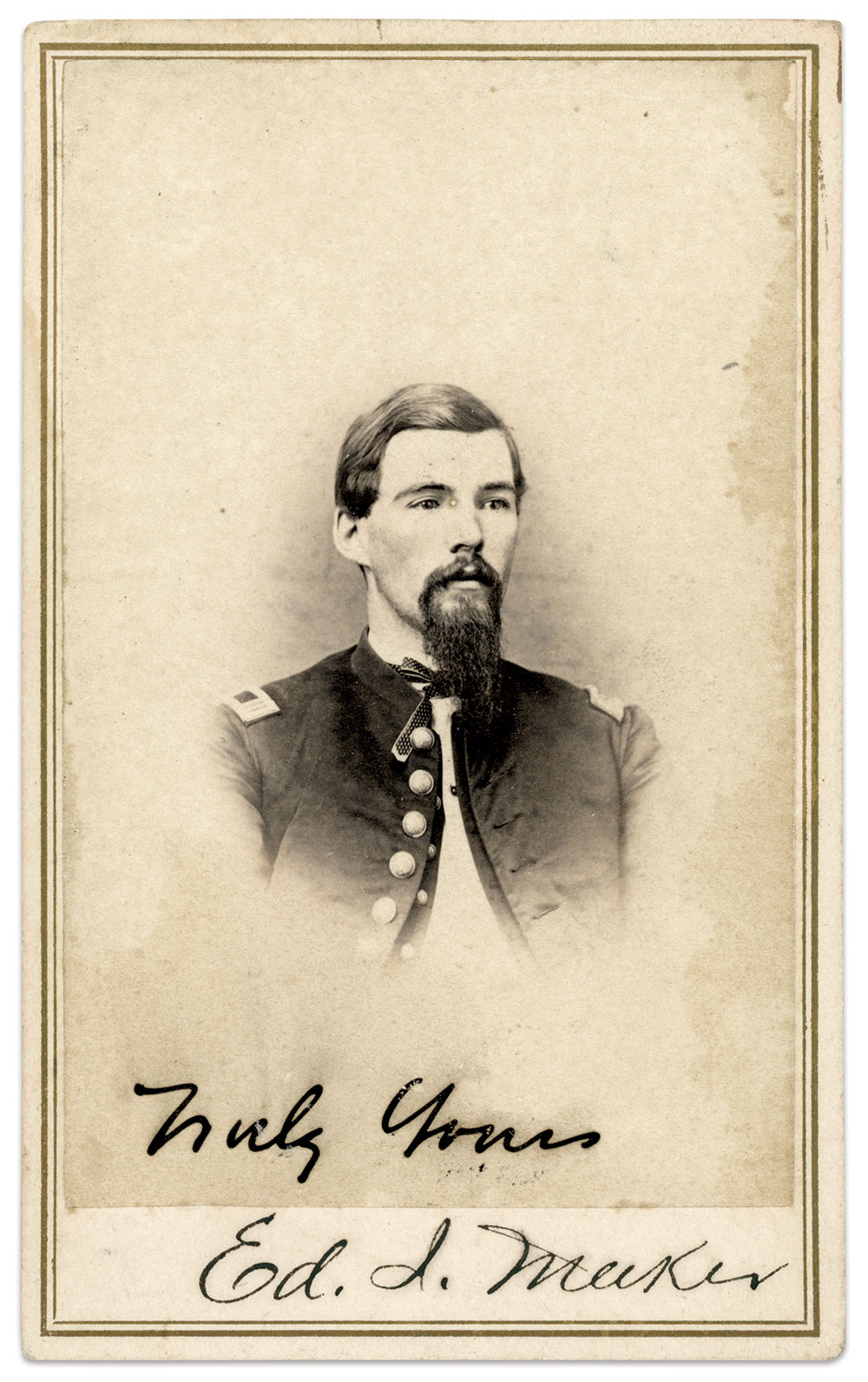

Three officers followed closely behind, including Capt. Edwin I. Meeker, a Missouri native who had been recruited for the corps from the 3rd Wisconsin Infantry back in 1861. He commanded the detachment.

As the men and officers established a routine at the fort’s South Barracks, its number was supplemented with five officers drawn from regiments in the region, designated as acting signal officers, including Quinby. In August, he and the others received a crash course on how to use and interpret signals—the method of aerial telegraphy popularly known as Wigwag for the waving motion of flags and torches—as well as the care of equipment.

Quinby and his comrades mastered the system in short order. As days and weeks passed, they and the rest of the detachment chafed with inaction, eager for active duty in the field.

Old Pap’s Play for Missouri

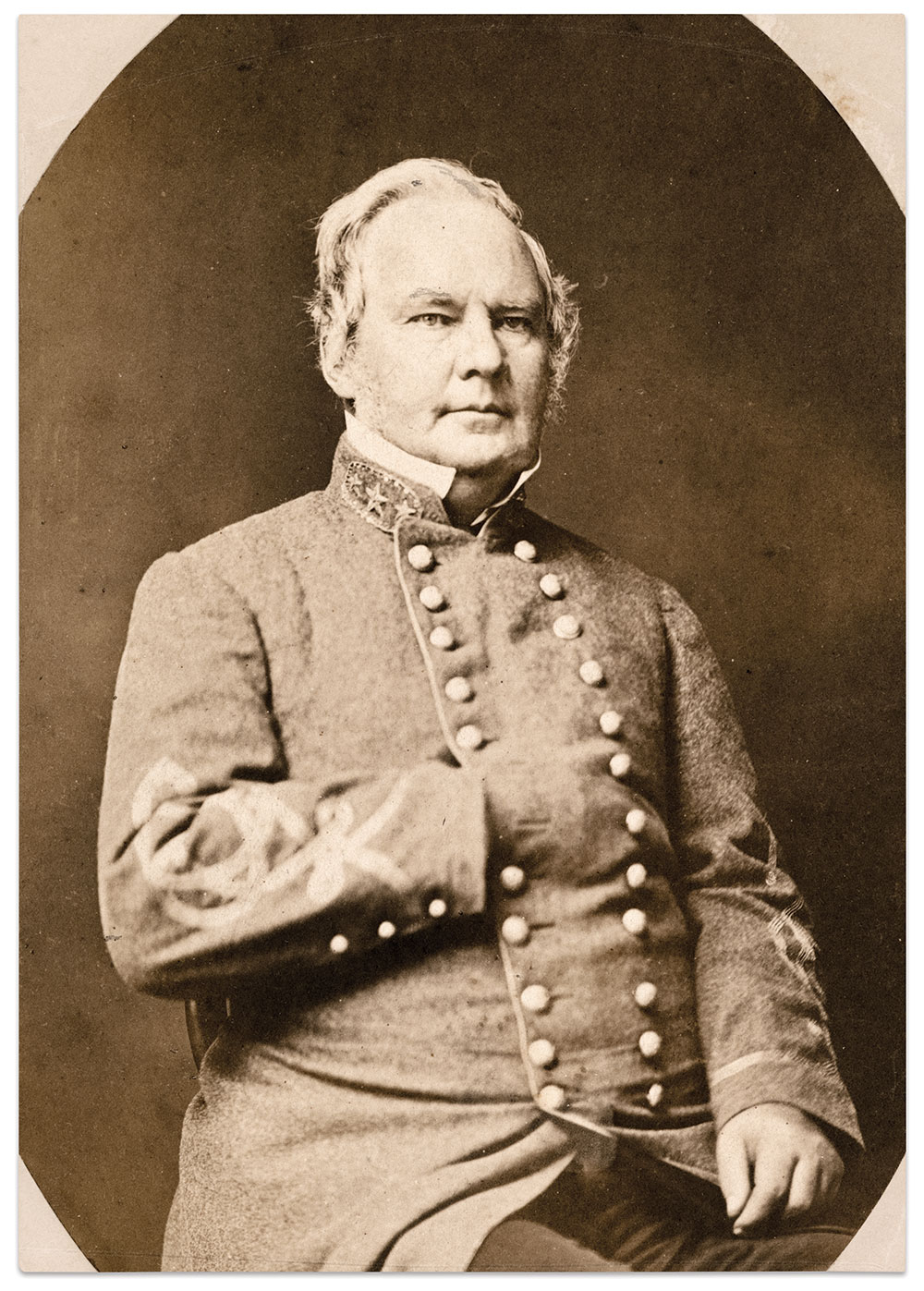

Many pro-Southern Missourians hailed Sterling Price as their knight in shining armor. The 55-year-old Virginian had settled in Missouri as a young man and rose to become governor, serving a term from 1853 to 1857 that brought many improvements to the state. He exuded courtly manners from his ruddy face framed by silver hair and whiskers, and every fiber of his six-foot two-inch frame. One admirer proclaimed, “What care we for Dixie Land of the happy land of Canaan, so long as Missouri was right in the front ranks with her General Sterling Price.”

“Old Pap,” as he was affectionately known by the troops, had been absent from Missouri since the heady days of 1861. Publicly a Union man and privately a secessionist, he had conspired unsuccessfully with Gov. Claiborne Fox Jackson to capture the state arsenal in St. Louis. Jackson then appointed Price to command the Missouri State Guard in a military takeover. The plan unraveled after U.S. forces led by Capt. Nathaniel Lyon occupied St. Louis and a pro-Union Constitutional Convention ousted Jackson.

Price, undeterred, led his guardsmen, supported by Confederate forces, to victory at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek, where Lyon died. Emboldened, Price pushed into northern Missouri and triumphed again at Lexington in September 1861. But momentum faded as Union reinforcements surged, forcing Price to withdraw south into Arkansas.

As the war unfolded, rumors of raids led to a common joke amongst Union citizens, according to an historian: “There were five seasons in the year—‘spring, summer, fall, Price’s raid, and winter.”

As the war unfolded, rumors of raids led to a common joke amongst the Union loyal populace, according to one historian: “There were five seasons in the year—‘spring, summer, fall, Price’s raid, and winter.”

Price’s best opportunity for a Missouri homecoming occurred when Trans-Mississippi Department commander E. Kirby Smith placed him in charge of a raid. In August 1864, Price assembled a 12,000-man force symbolically and optimistically named the Army of Missouri. Success would bring recruits and supplies, place the state under Southern authority, and influence the outcome of the upcoming federal elections—when democratic republics are most vulnerable.

On September 19, Price’s army crossed from Arkansas into southeastern Missouri, its three divisions spreading out and advancing towards St. Louis in columns. Brushing aside daily skirmishes with Union-loyal Missouri militia, the Confederates steadily progressed.

Meanwhile in St. Louis, William S. Rosecrans, the major general in command of the Department of Missouri, mobilized forces to meet the moment. He sent them after Price. The first significant action, 90 miles south of St. Louis at Pilot Knob, ended with Price’s forces repeatedly attacking Fort Davidson without success, its stubborn defenders abandoning it that night after blowing up the magazine. The St. Louis Democrat described the fight as “a carnival of blood” with an estimated 600-800 rebel casualties. The report called out the gallantry of Brig. Gen. Thomas Ewing, Jr., who led the fort’s defenders against overwhelming numbers of the aggressors.

His dream of occupying St. Louis dashed and out of options to take the city by force, Price had no choice but to turn his forces westward.

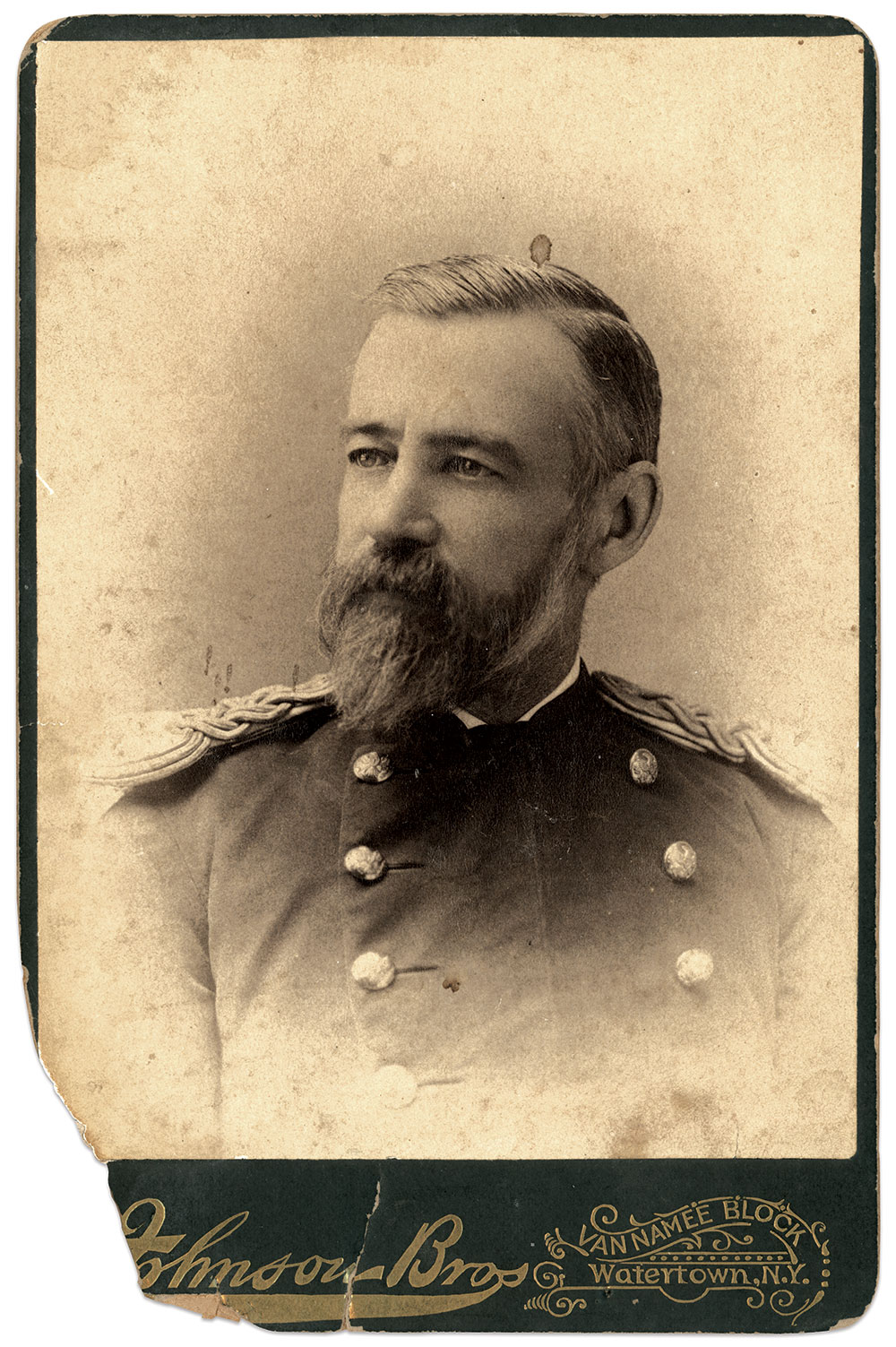

A Grant-Like General Prepares to Meet His Adversary

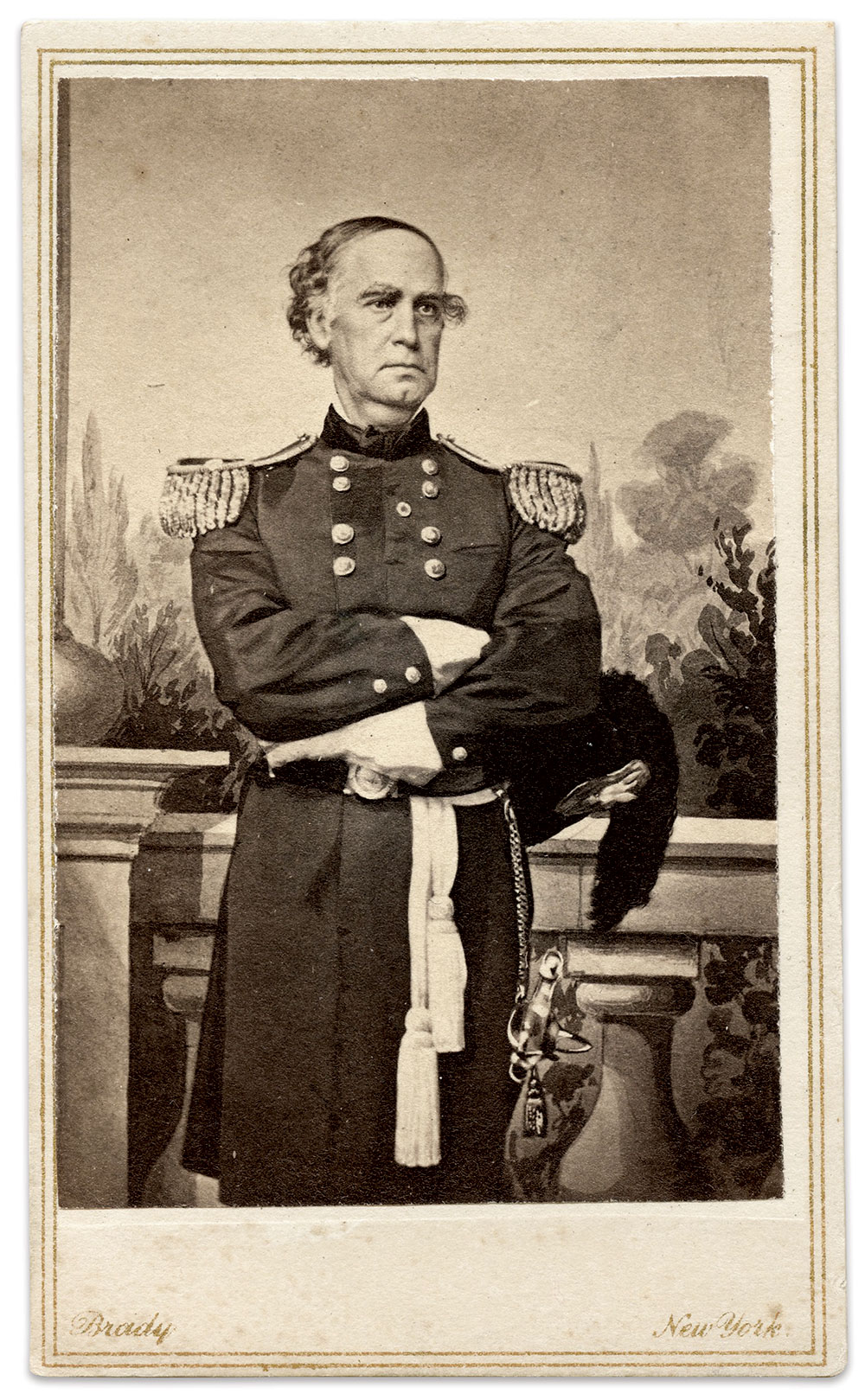

An admirer noted that Samuel Ryan Curtis bore a resemblance to Ulysses S. Grant in the way he waged war. A meticulous planner with a restless and inquisitive mind, the West Point-trained Curtis pursued victory with unflagging urgency. On the great chessboard of military maneuvers, he could hold his own against the best minds—though not especially brilliant himself, he was strategic and tenacious. Like Grant, he projected a sedate public presence, but in private he was sociable, approachable, and always careful not to give offense. Unlike Grant, he dressed scrupulously, his major general’s uniform conforming to regulations.

Curtis shared common ground with his adversary, Sterling Price: Both had served in the Mexican War and pursued political careers. Where Price championed slavery and states’ rights over a strong central government, Curtis, an ardent abolitionist, embodied E Pluribus Unum in its broadest sense, noted an admirer. Curtis’ political career had taken him, in the 1850s, to the U.S. Congress as a Republican representative from Iowa, where he championed a transcontinental railroad.

The two generals and their armies had clashed once before—in March 1862 at Pea Ridge, Ark., where he handed Price and the Confederates a significant defeat that secured much of Missouri and northern Arkansas for the United States.

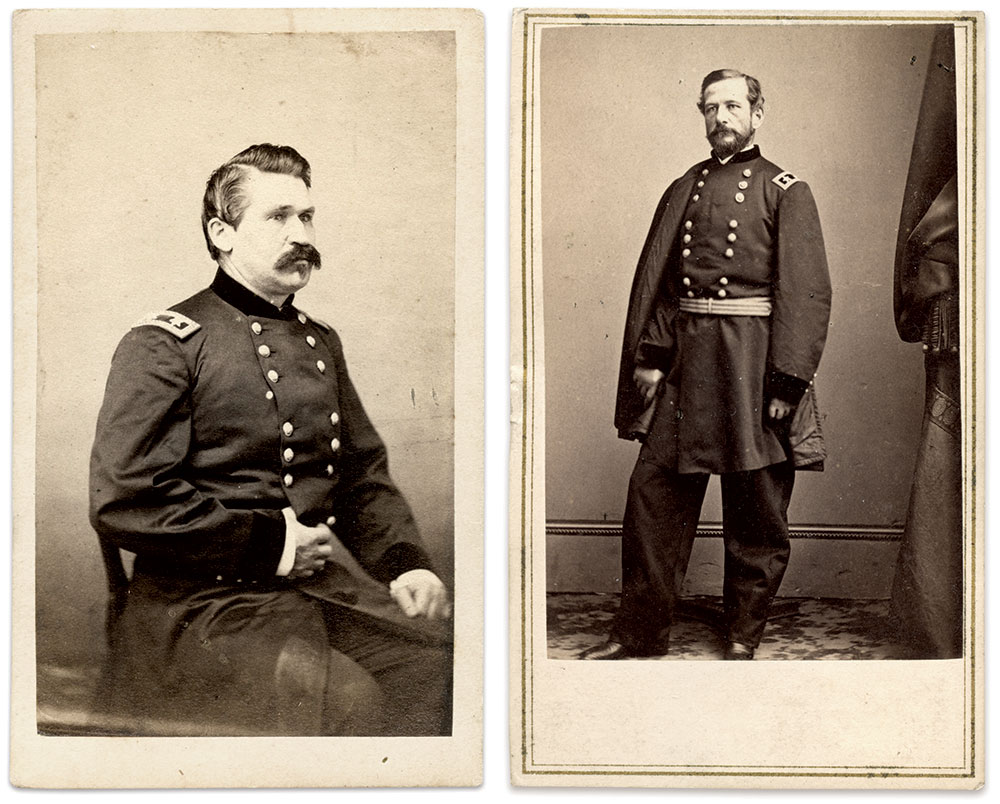

In September 1864, Curtis commanded the Department of Kansas with headquarters at Fort Leavenworth as Price turned his invading army away from St. Louis and headed in his direction. Curtis, with a few thousand troops to cover Kansas and the territories of Nebraska and Colorado, cobbled together a mix of volunteer and militia regiments commanded by major generals George W. Dietzler and James G. Blunt to form the roughly 16,000-man Army of the Border. Another 6,000 men, troopers from the Department of Missouri commanded by Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, bolstered the number of forces to about 22,000 effectives.

Meanwhile, Price’s raiders, now reduced to about 10,000, bypassed Jefferson City and marched towards Kansas City, Mo. Reports of rebel troopers looting farms and businesses and impressing able-bodied Union boys and men spread as Price advanced.

In early October, Maj. Gen. Curtis requested 25 signalmen to accompany his Army of the Border on an expedition into southern Missouri to stop Price. Every able-bodied man and officer in the Fort Leavenworth detachment volunteered and the requisite number selected. Captain Meeker picked four lieutenants for the assignment—including Quinby.

Defending Kansas City and the Union

At Fort Leavenworth, the seasoned instincts of General Curtis stirred to life. Consulting maps and sifting through the latest intelligence with the intensity of a chess master, he contemplated the next series of moves. With deliberate precision, he laid out a defensive strategy to block Price’s advance: a first stand at the Big Blue River, a second along the approaches to Kansas City, and a final fallback position within the city itself. Citizens were organized to dig earthworks. Warnings were posted to merchants and travelers. Steamboat owners and captains were encouraged to bullet-proof pilot houses and engine rooms.

At noon on October 11, Curtis and his staff mounted their horses and rode to meet the enemy. The Signal Corps, with fresh horses and a wagon, saddled up with 30 minutes notice and joined the advance. Curtis, short on staffers, attached four Signal officers to his headquarters during this early stage of operations: 2nd Lt. Julian R. Fitch as quartermaster, 1st Lt. Josiah M. Hubbard as assistant adjutant general in charge of returns, and 2nd Lt. Cyrus R. Roberts and Quinby as aides.

Captain Meeker left no record of his thoughts on the officers detailed to Curtis’s staff. But it’s easy to imagine he saw the assignment as a welcome development—after all, the Signal Corps was now temporarily embedded at the heart of army operations, within the commanding general’s headquarters.

Curtis trekked with part of his forces southward from Leavenworth to the vicinity of Independence, leaving the bulk of the Army of the Border arrayed along the elaborate trenches spread out for some 15 miles along the Big Blue, with smaller numbers of men garrisoning Kansas City and Westport.

On October 21 east of Independence, advance elements of Curtis’s army engaged in a sharp skirmish with Price’s vanguard along the Little Blue River. Notably for the Signal Corps, the rapidity of the fight did not present an opportunity for it to participate.

The situation changed for the signalmen as Union forces fell back along the Independence Road to its primary defensive line along the Big Blue. Early in the morning on October 22, as Price’s forces advanced on the well-entrenched federals, Capt. Meeker deployed two of his officers on opposite sides of the road, about three miles apart. With the assistance of a third officer to scope out advantageous positions, the men reported every 30 minutes by courier—the terrain being too dense for wig-wagging flags—to Curtis and his staff stationed along the road.

On the roof of the Harris House stood Quinby and Neely, intently watching the fighting unfold below them along Brush Creek among dense stands of timber.

According to Meeker’s official report, Curtis found the signal intelligence of great value and ordered copies of the messages forwarded in real time to his senior officers commanding the left, center, and right of the army: Maj. Gen. Dietzler, Col. Charles W. Blair, and Maj. Gen. Blunt.

Quinby was not directly involved in this effort. He likely remained with Curtis, monitoring and relaying communications between the couriers, Capt. Meeker, headquarters, and key commanders on the ground.

The Signalmen kept the couriers flying as the Battle of the Big Blue unfolded. Throughout the day, Blunt’s Kansans clashed with Price’s men, felling trees to block a critical ford and delay the enemy’s advance, and buying crucial time for Union reinforcements. Though outnumbered, the federals held key crossings before retreating to stronger positions.

By the close of fighting, Price’s raiders had crossed the Big Blue. But they stood in a precarious position—hemmed in by Curtis’ forces coalescing around the second line of defenses at Westport, the mighty Missouri River hugging the northern edge of Kansas City, and Pleasanton’s cavalry menacing them from the rear.

The Battle of Westport

The streaks of dawn’s light on Sunday, October 23, held the promise of a cool, crisp autumn day—and a momentous battle. Major Gen. Curtis had worked throughout the wee hours, scattering his aides into the night with orders to position his forces for the fight he expected. Price had followed suit, preparing for an all-out assault. Altogether, about 29,000 soldiers—about two-thirds blue and the rest gray—arrayed against each other.

Daybreak revealed Union troops from Maj. Gen. Blunt’s command marching into heavy timber, where they encountered elements of Confederate divisions led by Brig. Gen. Joseph Shelby and Maj. Gen. James Fagan. The Confederates hit hard, with reports of enemy artillery fire striking the streets of Westport, at least one shell landing in close proximity to the Harris House.

On the roof of the hotel stood Quinby and Neely, intently watching the fighting. They saw Brush Creek meandering through dense stands of timber. In front of them, on the north side of the creek, lay Blunt’s line of battle. On the other, south side, of the creek, the long lines Price’s forces stretching far and disappearing into the prairie. Drifts of sulfurous battle smoke wafting up from the firing lines, belching from musket muzzles and cannon tubes, suggested the advance of Blunt’s boys had stalled—a worrying sign that the federals were being checked and a Confederate onslaught lay in the offing.

Quinby and Neely had set up the rooftop post to observe and report to 1st Lt. Hubbard, who would relay intelligence to Curtis and staff. But the situation changed so rapidly that before they linked up with Hubbard, Curtis galloped into town as fast as his horse could carry him, with aides in tow. About 7:30 a.m., Curtis pulled up in front of Harris House, dismounted, and hurried to the roof—where he found the Signalmen and Maj. Gen. Blunt.

What, if any, pleasantries Curtis and his aides exchanged with Quinby, Neely, and Blunt is lost in time. Considering the heat of the moment, and Curtis’ personality, the greeting was likely cordial but brief. It is known that the two Signal officers shared what they had learned directly with Curtis—Capt. Meeker described them as “valuable observations” in his after action report.

The intelligence Curtis gleaned, coupled with his own observations and other information, contributed to orders he issued between 9:30 and 10 a.m. that he would lead an advance. By 11, Curtis and his escort reconnoitered the frontline positions, monitoring the progress on the ground, supporting his subordinates and making immediate command decisions to capitalize on positive gains, shifted the momentum of the fight.

The gathering of signalmen and commanders on the rooftop of Harris House is reminiscent of Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg.

In his official report, Curtis’ narrative captured a moment when the tide of battle shifted fully in favor of his army. He noted cavalry charges on Blunt’s front, the troopers dashing “forward with a terrible shout, carrying the heights and stone fences, which wreak havoc immediately occupied by our main forces, and I soon saw our line, extending far away on my right, merging from the dark forests of Brush Creek.”

Curtis continued: “The enemy was soon overpowered, and after a violent and desperate struggle fell back to another elevation on the broad prairie and operated their artillery and cavalry to their utmost ability in a vain attempt to check our general movement.”

At 11:30—about a half-hour after he arrived on the front lines, Curtis knew he had won the day. By 2 p.m. his forces linked up with Pleasonton’s cavalry and pushed the advantage, turning Price’s withdrawal into a rout and the raid a complete and utter failure.

Casualties in the three days of fighting from the Little Blue through Westport totaled about 1,000 for both sides.

The Gettysburg of the West

In his 1908 study, The Battle of Westport, historian Paul B. Jenkins calls out the similarities between the battles of Westport and Gettysburg. Jenkins explained that each resulted from campaigns planned by the Confederate War Department to invade Union territory. These campaigns forced the Union to consolidate soldiers and resources, thereby weakening the military presence in other areas and making them vulnerable to Confederate attacks. Major cities might have been compromised: Washington, Baltimore and Philadelphia in the East, and St. Louis and Kansas City in the West. Each battle lasted three days. In their respective theaters, they were the largest land battles, resulting in Union victories that ended future invasions.

Jenkins adds, “In spite, however, of the importance that may be thus justly claimed for the series of actions known as the Battle of Westport, those actions and their results have received but scant attention from the historians of the ‘Great Conflict.’”

The role of the Signal Corps in the Battle of Westport has also been paid scant attention. Jenkins does not mention the corps in his study. Other historians have largely ignored it. Even Curtis, in his lengthy official report, does not reference the signalmen. Thanks to Capt. Meeker’s report of the battle, and J. Willard Brown’s 1896 history, The Signal Corps U.S.A. 1861-1865, their contributions are known.

In light of the role of the Signal Corps at Westport, one more Gettysburg connection can be made: The gathering of signalmen and top commanders on the rooftop of Harris House at Westport is reminiscent of Little Round Top at Gettysburg. Major Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s interaction with the Signal Corps station along the ridge during the afternoon of July 2, 1863, and his own observations, provided clarity and spurred him to a series of actions that resulted in the successful defense of the Little Round Top—and, arguably, saving the Army of the Potomac from disaster and defeating Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. After Maj. Gen. Curtis witnessed the scene from the hotel rooftop, and what he learned from Quinby and Neely, and Blunt, led him to guide the battle to its successful conclusion.

Epilogue

The stinging defeat at Westport did not sit well with Maj. Gen. Price. In April 1865 he requested a court of inquiry to exonerate himself and preserve his honor. The commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith granted a hearing. But the war ended before action could be taken. Following the final collapse of the Confederacy, Price fled to Mexico rather than surrender. A failed attempt to establish a colony and declining health ended his Mexican dreams, and prompted his return to Missouri not as a conqueror, but as a proud man seeking to live out his remaining days.

His death at St. Louis in 1867 at age 58 prompted an outpouring of grief. Thousands of citizens paid their respects as his remains, dressed in a suit of black and white gloves, lay in state at the city’s First Methodist Church. The funeral procession, including 400 former Confederates and thousands of mourners, followed a hearse drawn by six black horses to Price’s final resting place in Bellefontaine Cemetery. Two years earlier, the same hearse had been loaned by St. Louis to the city of Springfield to carry President Abraham Lincoln’s body.

Following his victory at Westport, Maj. Gen. Curtis pursued the remnants of Price’s army into Arkansas, and returned to Fort Leavenworth. Though Curtis’ achievement could not be denied, praise and field command did not follow. In fact, it had eluded him since his Southwestern Campaign that culminated in victory at the March 1862 Battle of Pea Ridge—his first defeat of Price. One of Curtis’ subordinates at Pea Ridge, respected Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge, observed after the war, “I have never thought that General Curtis has received the credit he was entitled to for this campaign and battle,” continuing, “We who took part in this campaign appreciate the difficulties and obstacles Curtis had to overcome, and how bravely and efficiently he commanded, and we honor him for it.” Dodge added that “the Government, for some reason, failed to give him another command in the field, though they retained him in command of departments to the end of the war.”

Another officer, Capt. Addison A. Stuart of the 17th Iowa Infantry, observed in History of Iowa Regiments, a book completed in the war’s waning months and published in late 1865, “As a soldier, General Curtis is able, magnanimous and brave; and why, against his known wishes, he has recently been kept from the front, I do not understand. Perhaps he too much resembles the great military chieftain of the day; for I have noticed that, in nearly every instance, commands at the front have been given to those who, as regards sprightliness and dash, are the direct opposites of General Grant.”

Curtis’ final wartime assignment, on the heels of Westport, came in January 1865. The War Department reassigned him to the Department of the Northwest with headquarters at Milwaukee, Wis. He replaced Maj. Gen. John Pope, who had been sent there after being relieved following his brief tenure as commander of the short-lived Army of Virginia and poor performance at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Pope, his reputation rehabilitated, received orders to command an expanded Department of Missouri.

Curtis’ new assignment seemed more punishment than reward.

In late 1865, Curtis concluded his service and returned to Iowa, settling in Council Bluffs serving as a commissioner for the Union Pacific Railroad. His untimely death in 1866 from a cerebral hemorrhage at age 61 deprived him of seeing the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad three years later.

First Lt. Quinby participated in the pursuit of Price. Upon his return to Fort Leavenworth, one of his duties involved taking possession of and processing 19 prisoners of war—15 of whom claimed to have been Missourians conscripted by Price’s raiders.

While Quinby attended to Signal Corps duties, his 1st Colorado Cavalry participated in an atrocity near Fort Lyon that sent shockwaves across the country—the Sand Creek Massacre. On Nov. 29, 1864, about 800 troopers of the 1st and 3rd Colorado cavalries and a company of the 1st New Mexico Infantry attacked a like number of Arapaho and Cheyenne women, children, and the elderly encamped along a bend of Sand Creek. The soldiers slaughtered an estimated 160 to 230 individuals, mutilating some bodies. A Congressional inquiry strongly condemned the commander, Col. John M. Chivington, but stopped short of a court-martial.

Quinby remained with the Signal Corps until May 1865, when his superiors relieved and returned him to the 1st. He remained on duty in Colorado Territory until mustering out of the volunteer army in November 1865.

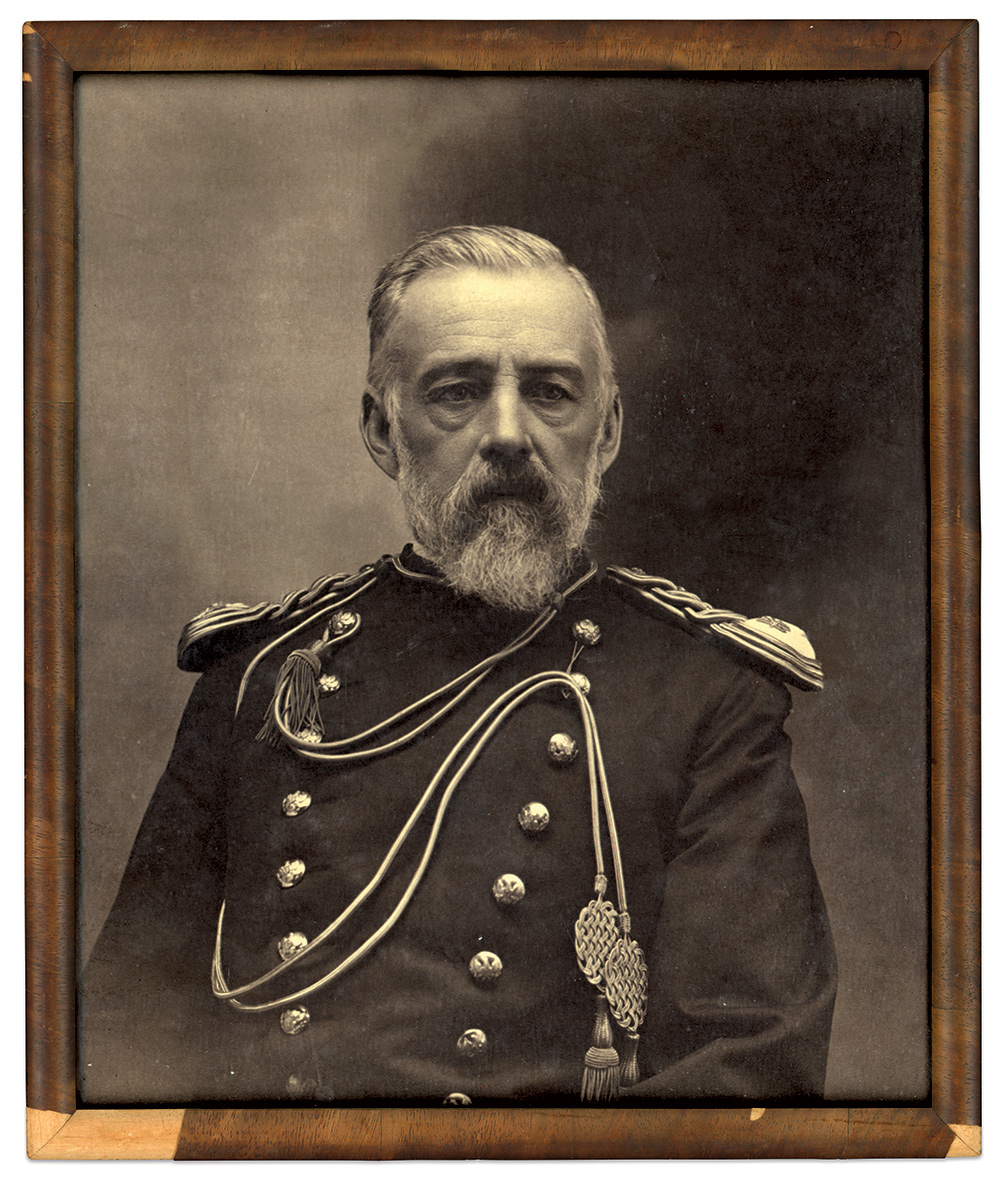

Military life had its appeal. In 1866, Quinby joined the U.S. Army as a second lieutenant in the 15th U.S. Infantry, and before the year’s end received a promotion to first lieutenant and assignment to the 24th U.S. Infantry, one of the new Buffalo Soldier regiments. Thus began a career than spanned the next four decades. He spent the majority of time on the Western frontier as settlers transformed the vast region.

In 1868, Quinby married and began a family that grew to include seven children born at various army posts and other locations around the country—a son born in 1869 to his wife, Caroline, who died in 1870, and four daughters and two sons to his second wife, Elie, the sister of Caroline.

As his family expanded, Quinby advanced through the ranks. He enjoyed a spotless record with the exception of a single blemish, an 1888 incident of drinking that ended with a court martial finding him guilty of conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline, and absence from duty. The court acquitted him on a charge of drunkenness on duty. Ten years later, he received a promotion to major. He ended his service in 1904 as a lieutenant colonel and died in his hometown of Morris, N.Y., in 1915. His remains, and those of his second wife, Elie, rest in Arlington National Cemetery.

Among Quinby’s surviving papers is a thoughtful 1895 essay written while he was a captain stationed at Fort Apache, Arizona. Titled “In Time of Peace, Prepare for War,” the piece reflects the culmination of a lifetime in military service. In it, Quinby applies the ancient maxim to a United States on the cusp of becoming a global power. He recognized that a self-governing republic, reliant on a small standing army and navy supplemented by volunteer forces in times of crisis, was not a flaw but a defining feature. Yet this structure, combined with the nation’s vast geography, also posed a strategic vulnerability—one that made advance planning essential. Preparedness, Quinby argued, would blunt the force of any enemy invasion: “A free, independent and brave people will not require a very great length of time to rally from disaster.”

References: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XLI, Part I; The Rocky Mountain News, Oct. 8, 1860, and April 27, 1866; The Colorado Transcript, April 13, 1905; Elswick, M.S., “Colorado Volunteers 1861-1865,” Colorado State Archives (undated); Military service records, National Archives via Fold3; Brown, The Signal Corps in the War of the Rebellion; Westport 1812-1912; Jenkins, The Battle of Westport; Monnett, Action Before Westport 1864; The Morning Herald, St. Joseph, Mo., Oct. 10, 1862; The Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 6, 1864; Stuart, Iowa Colonels and Regiments; Biographical Review, Biographical Sketches of the Leading Citizens of Otsego County, New York; The Kentucky Gazette, Oct. 5, 1867; Dodge, The Battle of Atlanta and Other Campaigns, Addresses. Etc.

Ronald S. Coddington is editor and publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.