By Kurt Luther

Portraits of Civil War couples have long captivated me. They capture a fleeting moment of togetherness, a quiet counterpoint to the distant bugles and battles. We see not just a soldier in uniform but a husband; not just a woman but a wife whose gaze often betrays a mix of pride and anxiety. These images are intimate and profoundly human, forcing us to consider the personal lives at stake.

Like other Civil War photos, the majority of couples’ portraits are unidentified. I was recently reminded of this reality when paging through the online Liljenquist Family Collection of the Library of Congress, which includes more than 50 such photos of mystery couples. I had not written about photo sleuthing a Civil War couple’s portrait since the Winter 2017 edition of MI, when I shared Laura Elliott’s story of identifying a Georgia corporal and his wife. The time seemed right for a new investigation, and one particular carte de visite caught my attention.

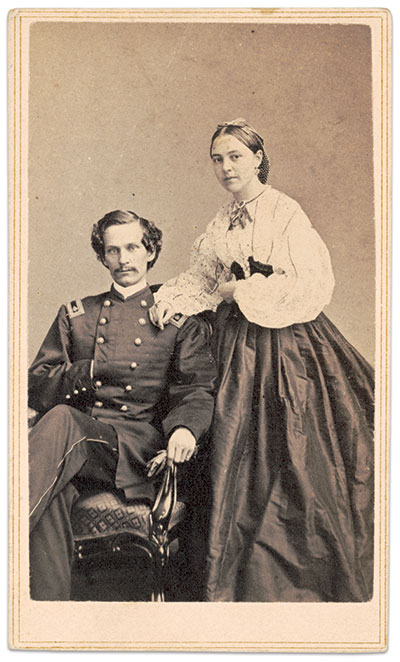

In this unidentified carte, the man is seated and the woman stands beside him, one hand resting on his shoulder in an affectionate manner. The man wears a field-grade Union officer’s coat over a high-collared shirt and large shoulder boards displaying the oak leaves of a major or lieutenant colonel. His large coat buttons and dark-colored pants suggest a staff officer. His left hand grasps a pair of gloves, while his right one is tucked into his coat in the martial “hand-in-waistcoat” gesture. He has a full head of coiffed, wavy hair and a mustache drooping over thin lips and a cleft chin.

The woman beside him wears a snood over neatly parted hair, a light-colored blouse with bishop sleeves, and a dark skirt. Her jewelry includes a brooch at her neck with cascading ribbons, earrings, and at least one ring on her right hand. She looks toward the camera with dark, attentive eyes and a serious expression from a slightly turned pose.

The carte’s verso shows the distinctive decorative backmark of the well-known 19th century photographer Charles D. Fredricks’ studio, advertising locations in the cities of New York, Havana, and Paris. There is no tax stamp. At the bottom of the mount is a period pencil valediction, apparently hastily written and difficult to fully decipher: “Truly R[…]l, Juli[e?].”

Taken together, the portrait’s clues offer little more than the caption provided by the Library of Congress: an “unidentified soldier in Union uniform with unidentified woman, probably his wife.” Yet the handsome young couple, both gazing directly at the viewer, seemed to invite me to dig deeper. Perhaps the man’s distinctive hair and facial features, combined with the mysterious note from “Julie,” would provide enough of a lead to move the investigation forward.

First, I tried a simple reverse image search but didn’t find any matches. Next, I turned to Civil War Photo Sleuth (CWPS, www.civilwarphotosleuth.com), the website my team created that combines AI-based facial recognition and human expertise to help identify unknown Civil War portraits. I focused on the male subject first since our reference database has many more reference images of soldiers than civilians, and his uniform allowed me to narrow down the possibilities to just those Union officers who held his rank at some point during the war years.

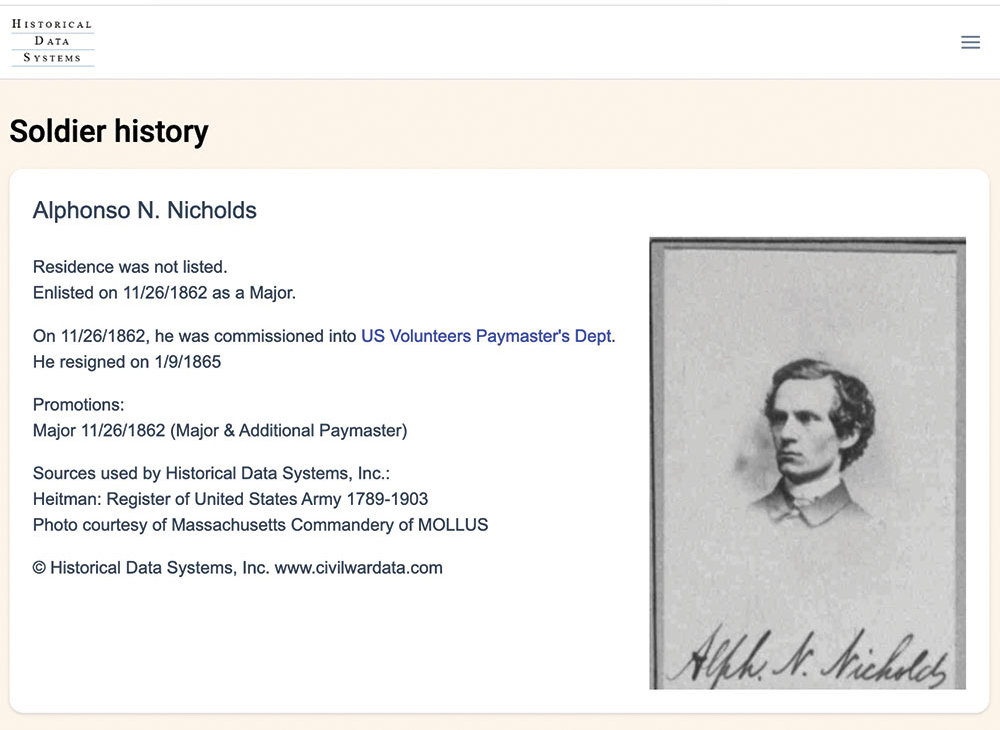

The CWPS search results returned 19,223 photos of Union majors, lieutenant colonels, and surgeons. I used the site’s newer, stricter facial recognition model to narrow down these thousands of matches to only those whose facial features strongly resembled the mystery officer. As I had hoped, his unique visage dramatically culled the possibilities—more than 19,000 results were instantly whittled down to just seven, ordered from most to least similar. The top-ranked result was a man named Alphonzo N. Nicholds.

Nicholds, according to the brief biographical details available on the American Civil War Research Database (HDS), was a major in the Pay Department, U.S. Volunteers. The reference photo provided by HDS showed an autographed, vignetted bust view of a man who looked nearly identical to my unknown officer. The same wavy hair, thin lips, cleft chin, and even the high collar were all present—only the mustache was missing. Nicholds could have grown or shaved his mustache during his over two years of service, but since his rank never changed, it was hard to say which photo came first. I knew I needed to conduct additional research to firm up this potential identification.

My next goal was to find more reference images of Nicholds. The original source of the HDS reference photo was the MOLLUS collection from the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center (USAHEC), one of the world’s largest archives of Civil War portraits, especially Union officers. Unfortunately, USAHEC was in the midst of a website upgrade, and the tens of thousands of digitized soldier photos that are typically available for free online were inaccessible. Further, a red banner emblazoned on every web page helpfully reminded me that due to the U.S. government shutdown, the office was closed and staff were unavailable to assist.

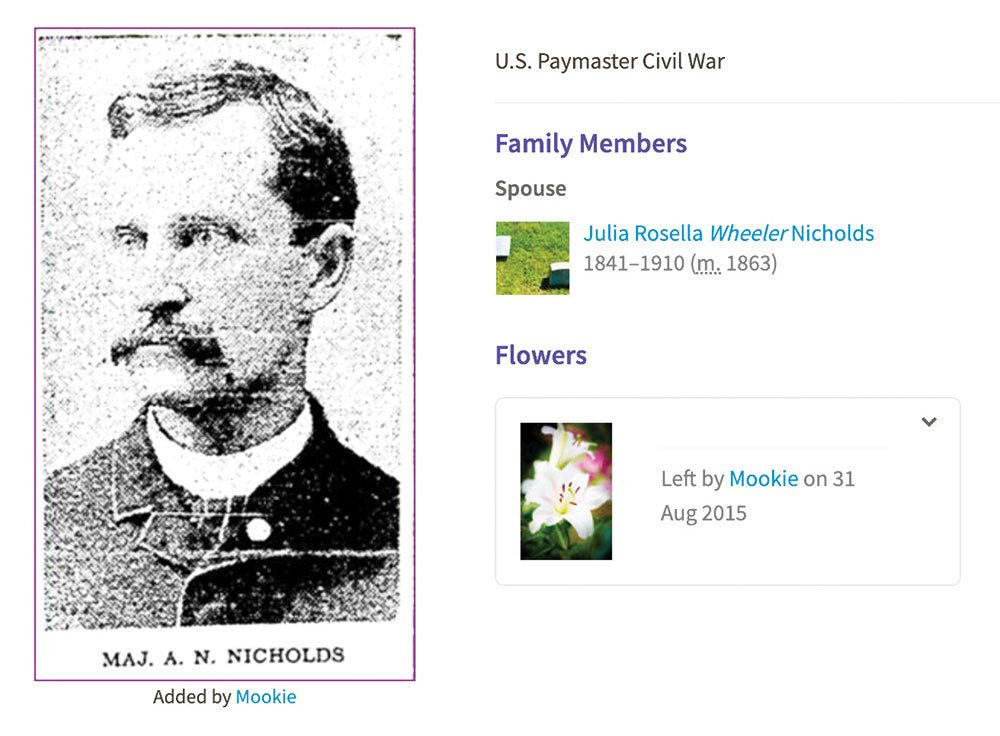

I knew I’d have to look elsewhere. My next stop was Find a Grave, an online database of gravesite locations, photos, and biographical information of the deceased. Nicholds had a unique name to complement his unique face, and I felt confident that if his profile was on Find a Grave, it would be easy to find with a basic search. Find a Grave pages often include user-contributed content such as portraits and obituaries that are hard to find elsewhere, and in Nicholds’ case, I was not disappointed. Not only did he have a profile and a photo of his gravesite, but the profile also featured a postwar portrait of Nicholds copied from a 1930 newspaper article. The image was creased and overexposed, but it was unmistakably Nicholds, with the same gaze, lips, and chin as the HDS reference photo. He was a few years older and his hair a bit thinner. There was one more difference—this Nicholds sported the same droopy mustache as the man in my mystery photo.

The Find a Grave page offered a cornucopia of key information about Nicholds, including his middle name (Noble), life dates (1841–1912), and birthplace (Wilkes-Barre, Pa.), that I later verified through primary sources. Several obituaries extracted from contemporary newspapers were also posted. Most useful of all were the links to other memorial pages for his relations. The moment I read his wife’s name, I knew I had identified the right couple. Her name was Julia Rosella Wheeler Nicholds. Truly, it was “Julie.”

As I researched Alphonzo and Julia, other pieces of the puzzle fell into place. After Alphonzo was born in Pennsylvania, his father, Almon(d) M. Nicholds, moved the family to Albany, N.Y. By the 1860 U.S. census, Alphonzo, about 19 years old, was working as a bookkeeper in Milwaukee, where he would meet Julia Wheeler, a native of that city and Daughter of the American Revolution. The next few years would be momentous for the couple. Soon after the outbreak of the Civil War, in August 1861, Almond enlisted as a wagoner in the 44th New York Infantry, of Little Round Top fame. Incredibly, a member-created family tree on Ancestry.com includes a wartime carte de visite group portrait of Alphonzo and Almond. The son stands tall and clean-shaven in a civilian suit beside the father, seated with a federal forage cap on his lap.

Sadly, Almond’s military career was short-lived. He contracted dysentery and died on a hospital ship en route to Philadelphia, just a few weeks shy of his one-year anniversary in the service. Alphonzo may have been moved by his father’s death, if not his patriotism, when he decided to join the army just three months later, in November 1862, accepting a major’s commission as an additional paymaster. Alphonzo and Julia married in Milwaukee the following year, on September 15, 1863. The couple must have sat for their portrait, with its Fredricks (New York) backmark, after the wedding but before August 1864, due to the lack of a tax stamp on the mount. By this time, Alphonzo had acquired a mustache, symbolizing his transformation into a soldier, husband, and patriarch.

Alphonzo served in the Paymaster Corps for over two years. In December 1864, he wrote to President Lincoln requesting to tender his resignation due to “disease of my right lung contracted during the last payment of the Army at Atlanta, Ga.” His request was approved in January 1865. He and Julia moved to Rockford, Illinois, constructing a fine house on Park Avenue the following year. They lived most of the rest of their lives in that Rockford home, raising a son and two daughters. Alphonzo was the Illinois state agent for the Equitable Life Insurance Company and proprietor of a boardinghouse.

In the 1890s, for unclear reasons, the couple began a series of moves around the country, with census and newspaper records finding them in Palo Alto, Calif. (1896); Ocala, Fla. (1900); and Richmond, Va. (1904). By 1910, they were back in Rockford, where Julia died on November 16. Alphonzo followed her two years later, on June 26, 1912. Both were laid to rest in Rockford’s Greenwood Cemetery.

Alphonzo was proud of his contributions as an army paymaster, an under-appreciated role, both then and now. The work demanded numeracy, responsibility, and energy—all of which he had in abundance. He described traveling to many major battlefields and, in one anecdote, transporting $3 million in cash to pay troops in New Orleans. One news item even claims that in 1873, the U.S. Pay Department approached Nicholds and invited him to re-enter the service, an offer that he ultimately declined. He was a member of the Col. Garrett L. Nevius G.A.R. Post No. 1 in Rockford, where his funeral was also held.

Portraits of Civil War couples capture a fleeting moment of togetherness, a quiet counterpoint to the distant bugles and battles.

In 1930, Alphonzo’s three adult children donated his army commission to the G.A.R. post. His obituary notes that the commission “was one of his most prized possessions” and “was once recovered from the bottom of the Mississippi River,” causing the signatures of Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to be faded almost beyond legibility. The G.A.R. members received the document with gratitude.

Nearly a century later, we again remember Maj. Alphonzo Nicholds and his wife, Julia, through the identification of their shared portrait. The moment captured on camera reflects the bright beginning of their relationship that endured the Civil War years and flourished into a family.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech. He is the president of The Photo Sleuth Foundation, a nonprofit organization with a mission to rediscover the names and stories of unknown people in historical photos through research, technology and community. He is a MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.