By Scott Valentine

Seeking to relieve pressure on the Army of Northern Virginia besieged at Richmond and Petersburg in the summer of 1864, Gen. Robert E. Lee ordered a diversion in the Shenandoah Valley. Lee entrusted the assignment to Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early and his Army of the Valley.

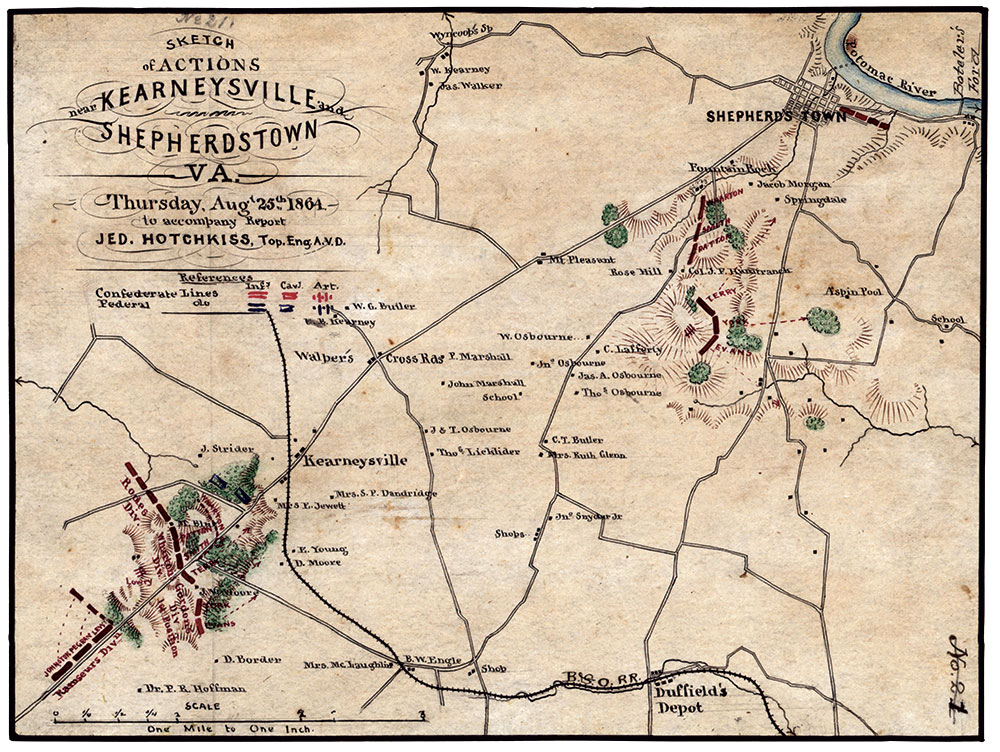

During the morning of August 25, Early took the majority of his army on a reconnaissance in force toward Shepherdstown and the Potomac River.

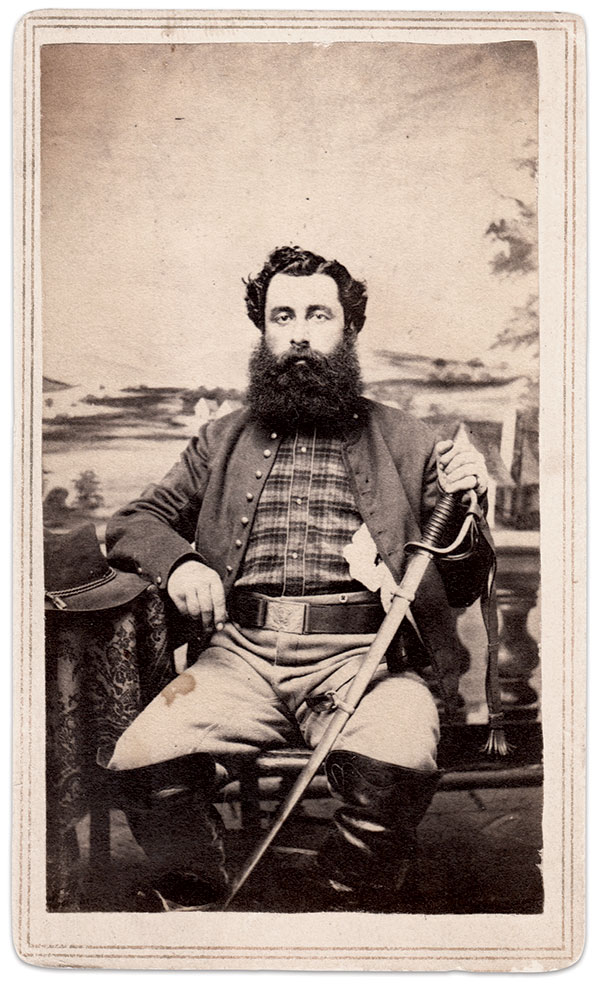

At the same time, two Union cavalry divisions from Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s command embarked on a reconnaissance. Among the troopers riding into action was George Manning Wingrove of the 9th New York Cavalry. An immigrant from Dublin, Ireland, he had recently been promoted to quartermaster sergeant.

Wingrove and his comrades rode towards Early’s northern flank and collided with his pickets at Kearneysville, W. Va. After a sharp fight of about half an hour the Confederates fell back, closely pressed by the Union troopers for nearly a mile. At one point a Union charge of over 2,000 horsemen bearing repeating carbines appeared to blunt the Confederate advance.

A flanking movement of the Confederate infantry, however, caused a hasty Union retreat toward Shepherdstown at around 1 p.m. Early’s mounted troops and his infantry pursued them. When the Union troopers attempted to make a stand just south of Shepherdstown, the Confederates attacked and forced the Union troopers to retreat toward Halltown, Va.

During the Shepherdstown stand, Wingrove received a saber cut along right side of his skull—fracturing the bone that protects the parietal region of the brain. He kept up with his fellow troopers and avoided capture despite copious streams of blood that ran into his eyes and impaired his vision.

Wingrove gained admission to Patterson Park Hospital at Baltimore two days later. He returned to active duty on October 5 and finished the war with his regiment.

Wounds like Wingrove’s were rare during the war. Of the 245,790 wounded Union hospital patients, only 522, or .2 percent, were victims of cavalry sabers. Only 26 of them proved fatal. This was perhaps because although sabers were designed for fighting, they were rarely used for such. In most cavalry skirmishes, especially in the densely wooded countryside of Western Virginia, the pistol and carbine were weapons of choice.

Saber blows to the head sometimes resulted in epileptic seizures, loss of vision or hearing, or impaired mental faculties. In the postwar period, doctors attending to veterans who suffered this type of wound attributed diminished cognitive function to the head injury.

Wingrove suffered from the lingering effects of the wound for the rest of his life. Unable to work because of the saber cut, he and his wife, Hester, and two children relied on his $50 monthly pension to survive. Wingrove died at age 60 in 1894.

Scott Valentine is a MI Contributing Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.