By Elizabeth A. Topping, with images and ephemera from the author’s collection

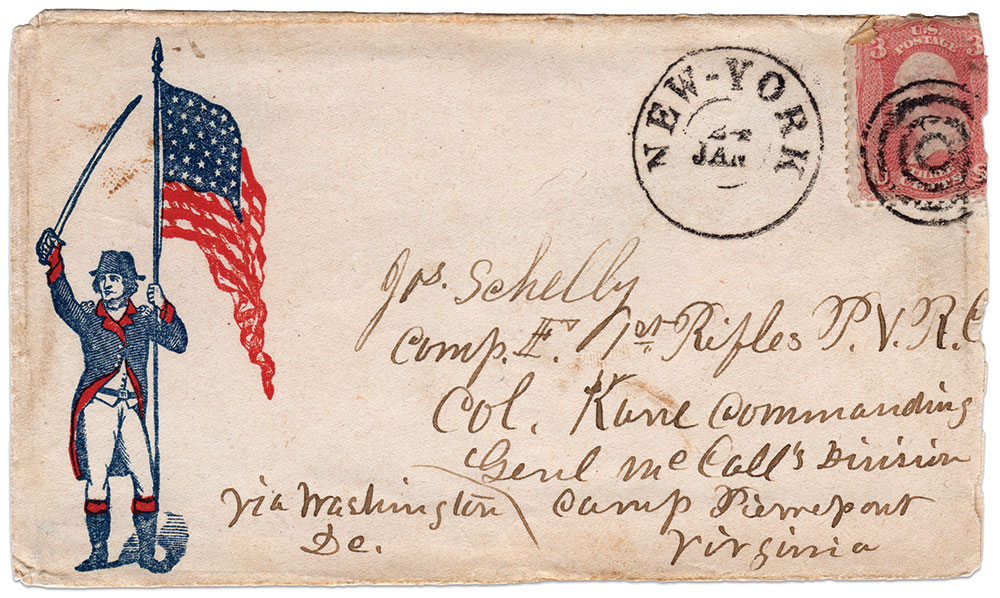

Mail call never failed to break the monotony of camp life and stirred anticipation among men and officers hoping for a letter or package from family or friends. One such delivery to the Pennsylvania Bucktails at Camp Pierpont in western Virginia on a January day in 1862 included an envelope postmarked New York City.

The envelope, illustrated with an engraving of George Washington with sword raised in defense of the flag, was addressed to Cpl. Joseph Shelly of Company F, in care of the regiment’s commander, Col. Thomas L. Kane.

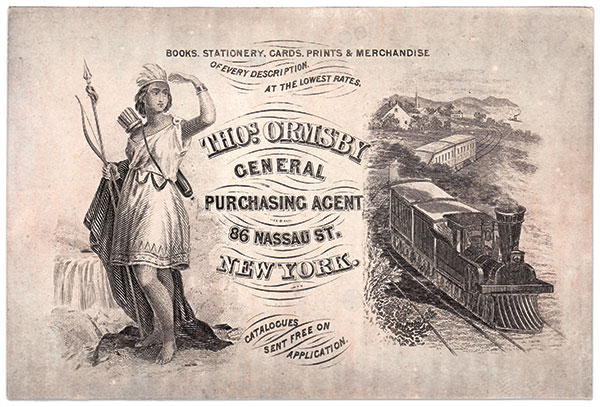

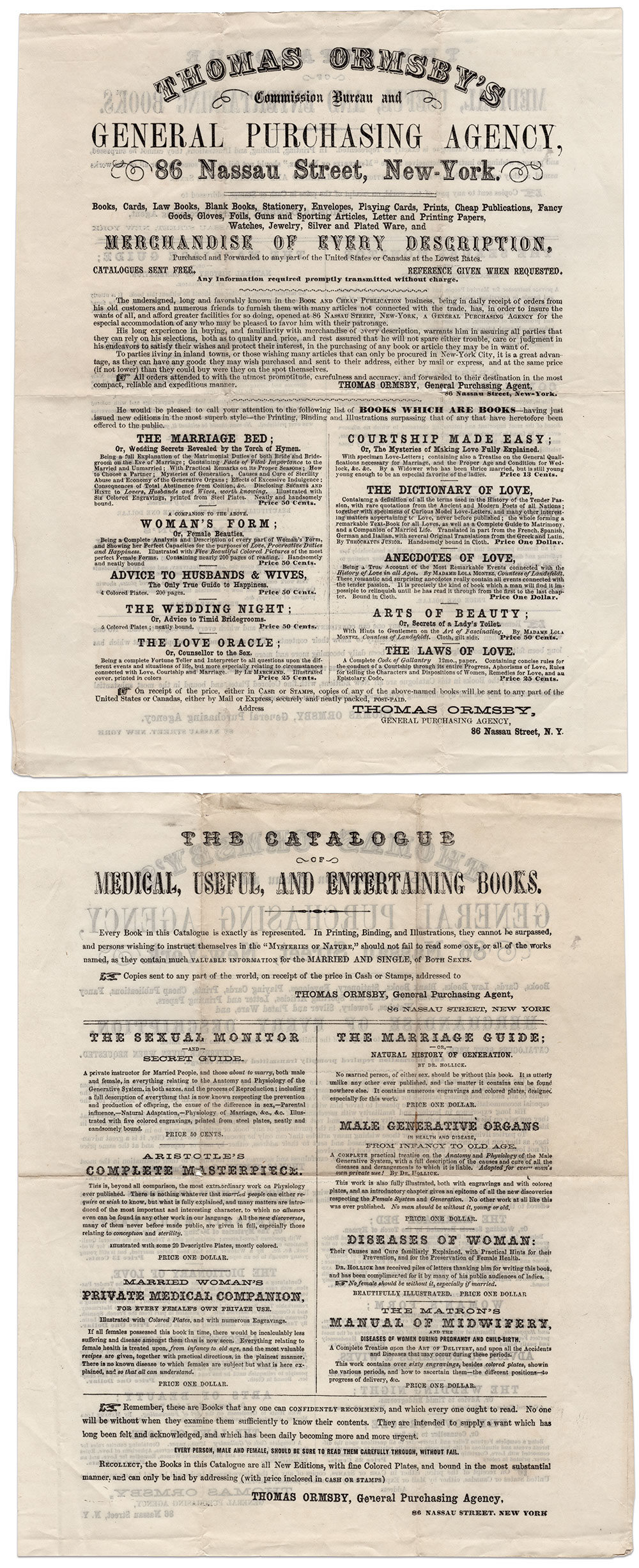

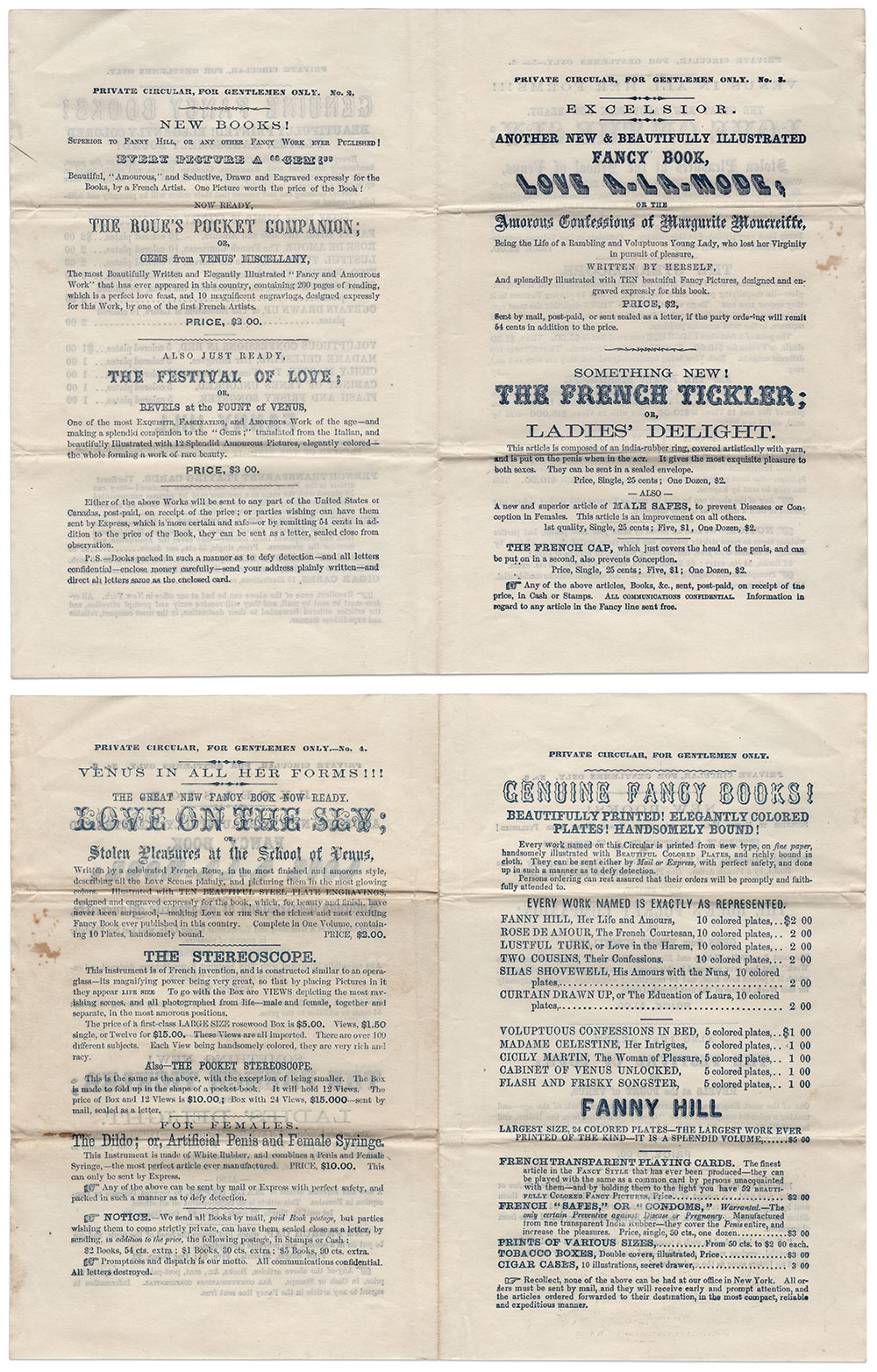

One can only imagine how Kane, 40, an abolitionist who had helped Mormons migrate west before the war, might have reacted if he had seen the contents: a four-page catalogue and a two-sided broadside of erotica and pornography offered for sale by Thomas Ormsby, a New York City book dealer. Ormsby also enclosed one of his illustrated business cards in case Shelley wished to share the titillating amusements with a pard without giving up his catalogues.

Ormsby started his business on Nassau Street in New York City in 1851. He was located in the center of the city’s thriving printing and publishing trade. Police arrested Ormsby three times in the 1850s for selling obscene material in his store. He and many of his fellow dealers turned from selling through a storefront to mail order to avoid the costs and restrictive local obscenity regulations.

Perhaps Cpl. Shelly responded to this ad placed by Ormsby in the Nov. 9, 1861, issue of The New York Clipper, which touted itself as a “paper for Sporting Men”:

GREAT BOOKS!!

NEW BOOKS! NEW BOOKS!

DON’T FAIL TO SEND FOR A CATALOGUE

OUR NEW CATALOGUE NOW READY.

—SENT FREE-POSTAGE PAID-ON APPLICATION

THE OLD ESTABLISHED AND ONLY RELIABLE BOOK, AND SPORTING GOODS AGENCY,

Where orders are promptly and faithfully executed.

Ormsby, posing as a seller of general merchandise, was able to discreetly sell erotica by mail. But those who knew the underground vernacular understood exactly what he was selling—pornography.

The term first appeared in Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the American Language in 1864. Webster defined it as a “licentious painting employed to decorate the walls of rooms sacred to bacchanalian orgies, examples of which exist in Pompeii.”

Other terms in use in the 1860s include “gay,” which in Ormsby’s business referred to the world of prostitution and brothels. A “sporting” man was one who frequented those institutions. “Racy” referred to anything sexually suggestive while “fancy” was code for anything sexually explicit and arousing. “Fancy” is the 19th century term for “hardcore.”

Other trigger phrases were “Rich and Rare,” “Cheap Publications,” “New Pictures for Bachelors,” “Cartes de Visite from Life for Gentlemen,” “Books for those who are Married or about to be Married,” “French Cards,” etc. All of these were sexually-oriented materials hidden within the offerings of stationary, law books and gloves.

Between 1862 and 1864 the number of ads for mail order erotica tripled. The illustration of a train on Ormsby’s business card showed his preferred method of delivery of articles for sporting men of every description. Mail delivery by rail started in the early 1860s making it easier to deliver illicit materials to soldiers in camp seeking erotic diversions to fill the hours between drilling and fighting. Postal workers sorted the mail en route in special rail cars, then deposited it at rail stations all over the country. Delivery was faster and cheaper by rail while offering privacy and anonymity for the buyer.

During the war, New York dealers exploited the demand from Union soldiers for mail order pornography including photography. Two new formats, the carte de visite and stereo card, were less expensive and more easily produced than daguerreotypes, ambrotypes or tintypes. Cartes de visite were small and easily hidden away. The larger stereo card, though harder to conceal, provided a three-dimensional lifelike view of the nude body when seen through a stereoscope or free-viewing.

Cartes de visite and stereo cards were easier and less expensive to mail as they were flat and not as fragile as glass images. Many erotic images were produced in France and sent to distribution houses in New York City. Cartes were generally priced at 25 cents while stereo cards ranged from 75 cents to two dollars, depending upon the subject matter.

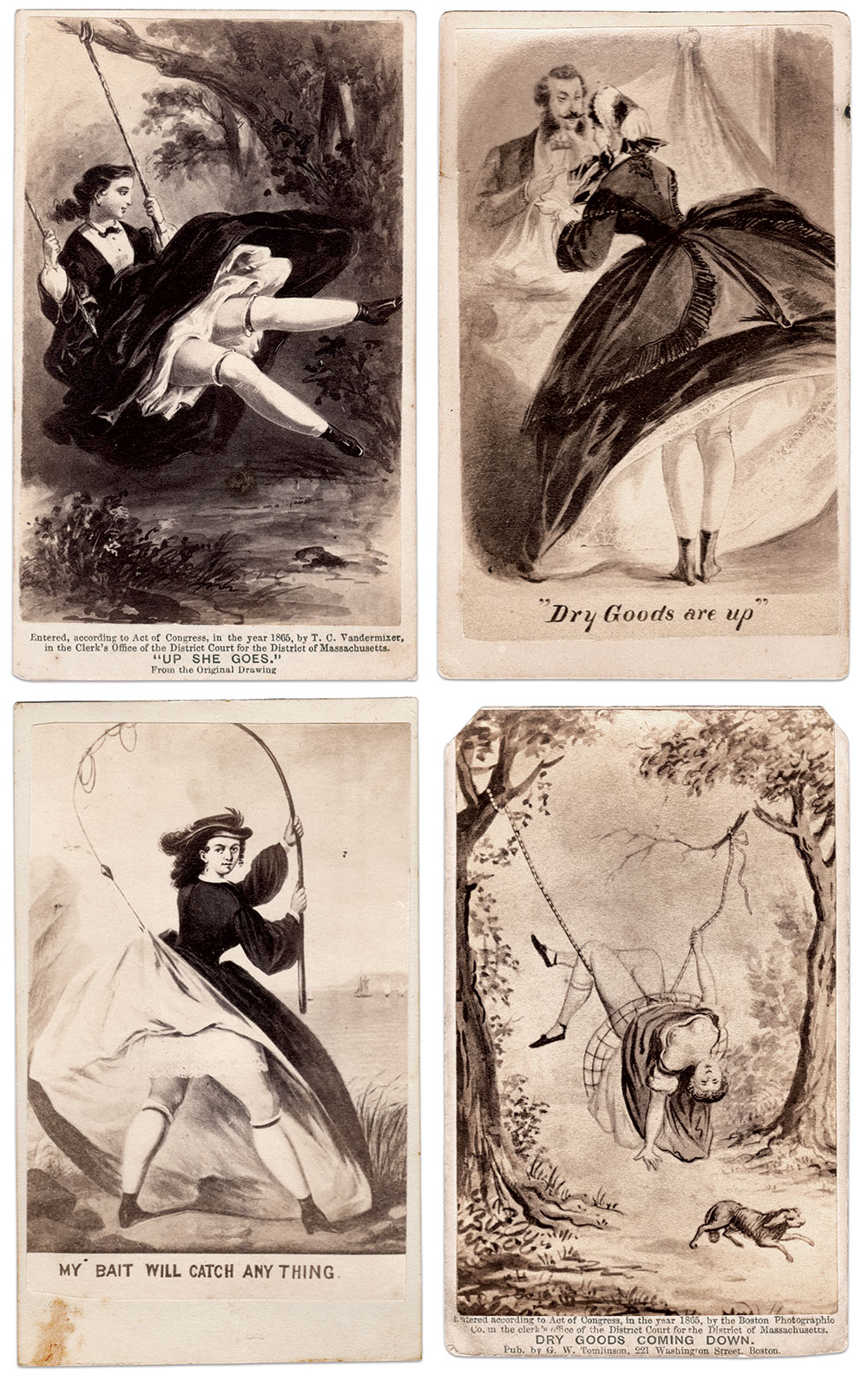

A popular strategy for satisfying voyeuristic erotic fantasies in revealing the female body showed women sleeping, bathing, or on swings where their “snowy globes” might be accidentally exposed, or a skirt raised above the knees to display the thighs—a highly eroticized part of the body in an era of long, wide skirts. These types of images would fall in the “racy” category and would not empty a soldiers’s wallet.

“Fancy” images showed explicit views of the naked body sometimes with the sexual organs hand-painted in reddish-pink tint. These were described as “the most ravishing scenes, all photographed from life—male and female, together and separate, in the most amorous positions.”

Erotic photographs provided visual stimulation for viewers that novels or pamphlets could not. Photos were less expensive than illustrated novels. One did not need to be literate to enjoy the photographs. Their small size made them easy to carry, share and trade with other soldiers without detection.

Postmaster General William Dennison became alarmed at the number of vulgar and indecent materials found in camp. In early 1865 he advised the Senate’s Post Office Committee that “our mails are made the vehicle for the conveyance of great numbers and quantities of obscene books and pictures.” He determined that these were a “great evil” and corrupted the morals of the men in the ranks.

President Abraham Lincoln signed a Senate motion into law on March 3, 1865, that allowed postal officials to “seize and destroy” obscene photos and publications discovered in the mail. However, they were not authorized to break seals to do so. This insured the privacy and safety of first-class mail. This law did not deter dealers in erotica. It inspired them to devise ways to elude detection by changing their packaging and shipping their products in first-class sealed envelopes.

About two months after Cpl. Shelly received the erotica, he and six companies of Bucktails in the 42nd Pennsylvania Infantry embarked on the Peninsula Campaign. On June 30, 1862, Shelly died in action in the Battle of Charles City Cross Roads. Thomas Ormsby would live to supply many more soldiers before he died on June 13, 1865.

References: Dennis, Licentious Gotham: Erotic Publishing and its Prosecution in Nineteenth-Century New York; Hawley, American Publishers of Indecent Books, 1840-1890; Tone, Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America.

Elizabeth A. Topping has been a reenactor and living historian for more than 25 years. Her collection and research focus on the social and material history of the Civil War. Her initial study centered on prostitution, which led to research on abortion, birth control and childbirth, female job opportunities and working conditions, medical treatment for poor and insane women, class and sex restrictions imposed on 19th century females, the roles of actresses in society, and the parts women played in aiding war efforts. Elizabeth enjoys sharing her expertise and artifacts for television programs, museums, magazines, conferences and roundtables. She is an MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.