By Kurt Luther

When photo sleuths hit a brick wall trying to identify the subject of a Civil War portrait, they often turn from the foreground to the background, using the photographer or the painted backdrop to shed light on the photo’s origin and help move the investigation forward. But what happens when the photographer and backdrop is also unidentified? In this column, we will see how researching unknown subjects and backdrops in parallel can be complementary, resulting in a likely location for the photographer’s studio and even a possible ID for the soldier.

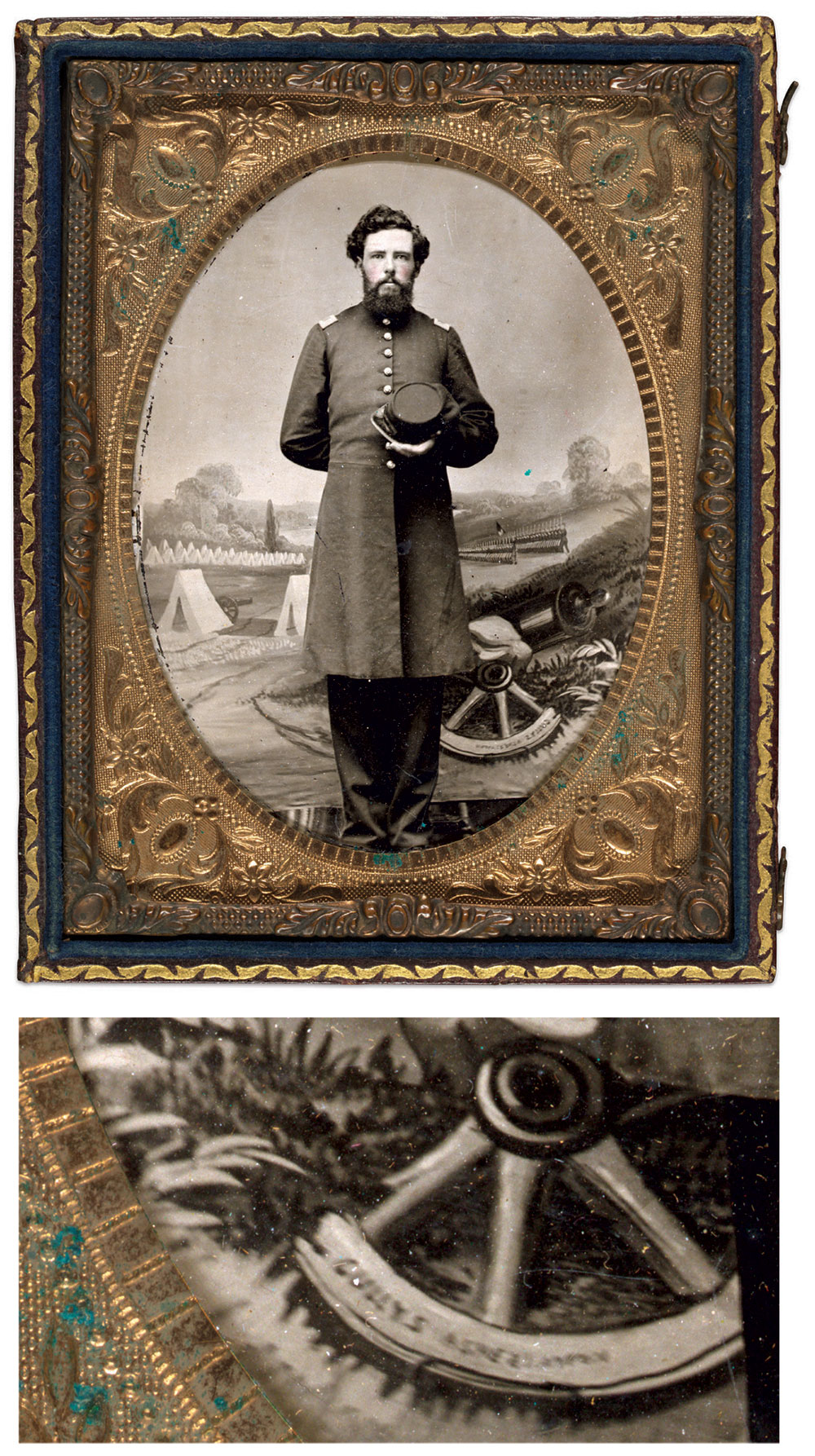

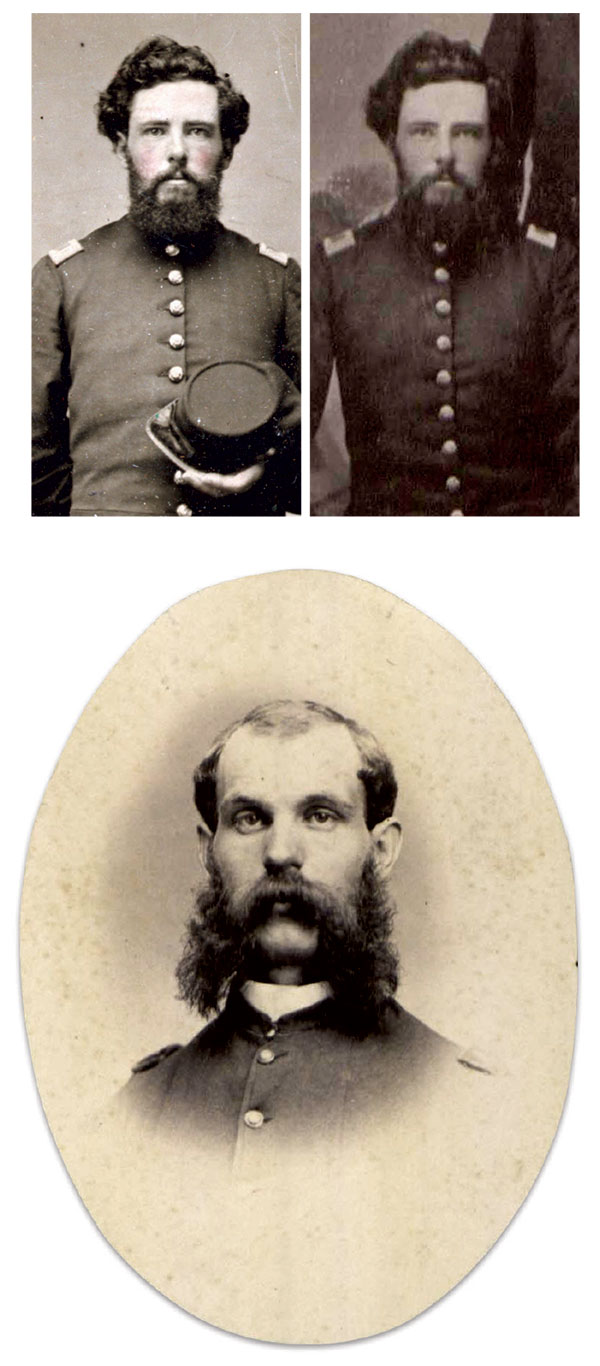

I was paging through the Library of Congress’s digitized Liljenquist Family Collection, looking for unidentified photos to investigate, when I came across a striking quarter-plate tintype of an unknown Union officer. The subject is a young man with a full beard, dark, wavy hair, and cheeks lightly colored by hand-tinting. He wears a junior officer’s frock coat with indeterminate shoulder straps—either one or two bars each—without a sash, belt, or other accouterments, and dark trousers. He places one hand behind his back, while the other cradles his unadorned cap.

Unarmed and lacking any distinctive uniform insignia, this young officer would be nearly impossible to identify this young officer, if not for the remarkable painted backdrop behind him.

The unique backdrop illustrates a battle scene with a wealth of intriguing details. In the distance, two rows of bayonet-wielding troops march down a hill towards a cluster of military tents surrounded by foliage. Closer to the foreground, a cannon peeks out behind one of two additional tents. Finally, and most striking, another cannon dominates the bottom-right quarter of the painting directly behind the mystery soldier. But this cannon has been destroyed; its tube lays on the ground beside half of a wheel.

Painted backdrops like this one can generate valuable leads for identifying the photo’s subject when nothing else is available. Many backdrops are believed to be unique to a particular studio. Even if the photographer name is unknown, finding a common backdrop can suggest the location where the photo was taken or links to identified soldiers or military units for follow-up research.

In this case, the painted backdrop and its associated studio were both unknown to me. After downloading the high-resolution TIFF file from the Library of Congress website, I zoomed in to inspect the details of the backdrop. I soon discovered a second mystery: the backdrop artist had painted some letters or words on the rim of the broken wheel. The text, already small, was further obscured because the tintype format reversed the image, so I used photo editing software to horizontally flip it. One word—possibly “CULLYS”—materialized into view. A second word, more illegible but possibly beginning with “ASH,” followed it. I theorized these could be the first and last names of the photographer or backdrop artist, but my searches of these names and variants on Langdon’s List and other 19th century photographer databases came up empty.

In a previous column (Summer 2023), I introduced Backdrop Explorer, a software tool developed by graduates of my lab at Virginia Tech, Vikram Mohanty and Jude Lim, that uses AI-based computer vision technology to help users find historical photos with similar painted backdrops. The software, recently renamed BackTrace, can match backdrops even when the associated photographers are unknown. Hoping for a break, I submitted the mystery officer’s photo to BackTrace.

I pored over the search results, and to my delight, I discovered two new photos with the same painted backdrop. The first was a tintype of Abraham F. Brown, a private in Company E of the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry, from the collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Brown, wearing his frock coat with gilded buttons and an oilcloth-covered cap, sits with his hands folded in front of the broken wheel, the mirrored “CULLYS” lettering clearly visible.

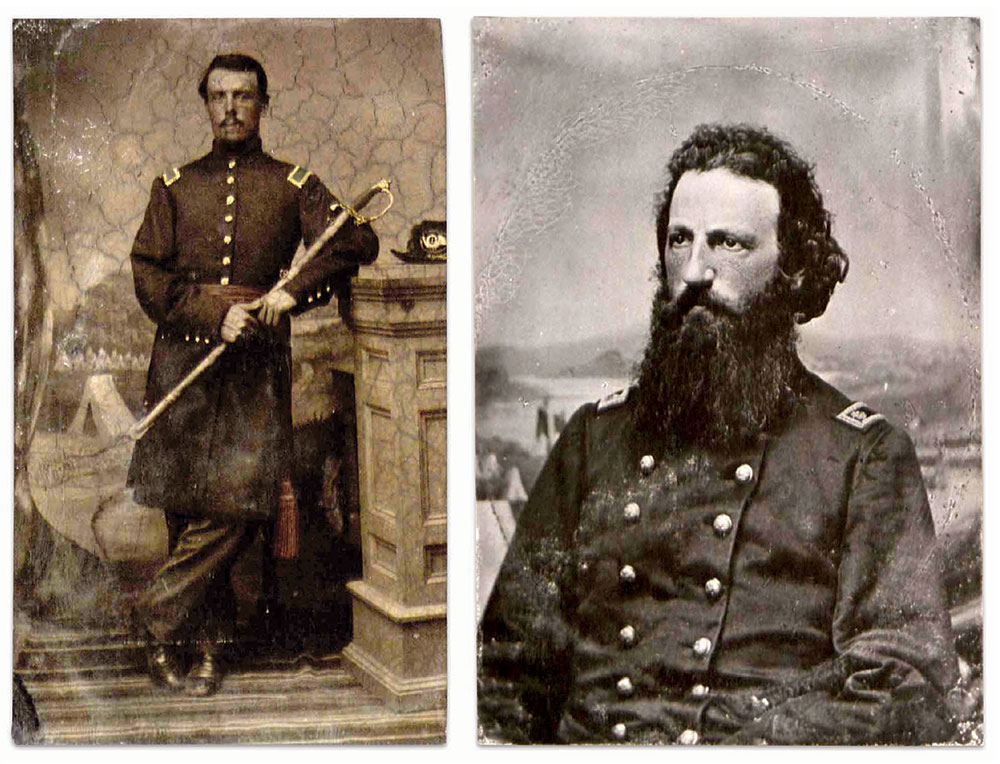

The second result was a carte de visite of 1st Lt. James B. West, Company K, 33rd U.S. Colored Infantry, originally from the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center (USAHEC)’s MOLLUS-Mass collection. West stands in full uniform, complete with ostrich-plumed hat, grasping his sword in one gauntleted hand. The broken cannon wheel is visible between his legs and the decorative post he leans against, and diamond-patterned flooring—a new clue—is revealed under his boots.

Besides the backdrop, these two photos had another obvious connection. Brown and West served in two of the most famous regiments of black Union soldiers, and both units spent considerable time in low country South Carolina. For example, the 33rd USCI—then known as 1st South Carolina (Colored) Infantry—was stationed in Beaufort, S.C., throughout 1863. The 54th Massachusetts spent a month in Beaufort before marching north to fight at James Island and Fort Wagner; after the battles, their casualties were sent back to the hospitals and cemeteries there. Was it possible that the broken-wheel backdrop came from a studio in Beaufort? Moreover, could it be that my mystery officer was also a member of one of these units?

I began searching two major repositories of identified Civil War portraits, Civil War Photo Sleuth (CWPS) and the American Civil War Research Database (HDS), for officers of the 54th Massachusetts and 33rd USCI. Given the historical importance of these regiments, there were dozens of reference photos available, but none presented a clear facial match to my mystery officer. However, I did find something almost as exciting: two more examples of the broken-wheel backdrop. The BackTrace software had missed these matches because the backdrop details were too faint—in fact, the broken wheel is obscured in both of them. Because my earlier research had narrowed the search to a couple of regiments, I was still able to discover them through manual inspection.

Both officers, like 1st Lt. West, were members of the 33rd USCI. In a cracked tintype, Capt. Charles W. Hooper of Company G leans against the same post as West, the rows of painted tents barely visible behind him. The second match was a three-quarter view of Maj. Seth Rogers, the 33rd’s regimental surgeon, surrounded by hints of marching troops and a cannon tube blurred by the camera’s shallow depth of field.

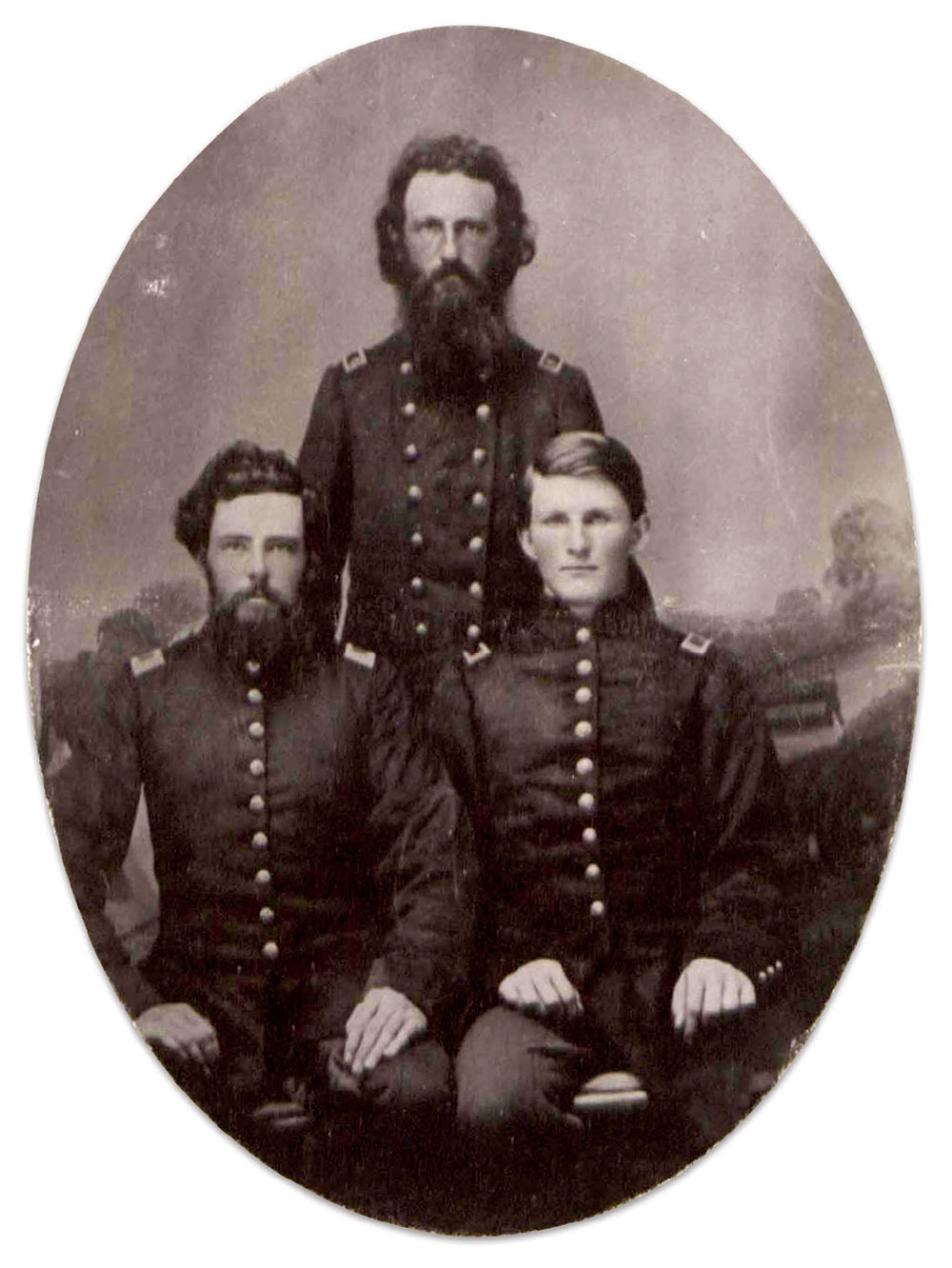

Having established a strong link between this backdrop and the 33rd USCI, I expanded my search for additional reference photos from this regiment. On the USAHEC website, my search pulled up two photos of Maj. Rogers. The first was the three-quarter view I had already seen. The second photo was new. It shows Rogers in the same studio with the broken-wheel backdrop, but this time standing behind two junior officers. According to the caption, the clean-shaven man on the right is Asst. Surg. Thomas Minor. The man seated on the left, his face identical to my mystery officer, is identified as Adjutant George W. Dewhurst. I had found my man.

It is possible that this group portrait was taken in the very same session as the solo images of Rogers and the mystery officer newly identified as Dewhurst. Their uniforms and hairstyles look identical in both images, and besides the poses, there are no obvious differences, though admittedly we would expect few. My search of CWPS and HDS did not turn up this photo because CWPS contains few group portraits and HDS only supports one photo per soldier. Fortunately, my investigation took me from the 33rd USCI to Maj. Rogers and ultimately to the USAHEC collections.

My excitement soured, however, when I noticed the rest of the 33rd USCI photos on the placard surrounding the group portrait. Above and to the left, only a couple of inches at most from the group portrait, was a solo portrait captioned, “Lieut. Geo. W. Dewhurst / Adjt.” Yet, this portrait showed a completely different man—mutton chops and a shaved chin instead of a full beard; hair that is thinning and cut short instead of thick and wavy. Baffled, I couldn’t imagine how the panel’s creator could inscribe the same name on two clearly different faces next to each other.

Although the MOLLUS collection’s IDs are usually highly trustworthy, this would not be the first time I found errors (see the Spring 2022 column). The contradiction suggested two possibilities to me. Either the mystery officer was George Dewhurst, or the solo portrait was. But if the man in the group portrait wasn’t Dewhurst, who was he?

I considered the composition of the portrait, with Maj. Rogers standing over two younger men who he likely knew well. Assistant Surgeon Thomas Minor (his middle initial variously appears as T, J, and S) makes perfect sense as one of Rogers’ two direct subordinates, and another reference photo of Minor in the MOLLUS collection confirms the ID. Rogers served in the 33rd for exactly one year, from December 1862 to 1863, so this time window constrains the possibilities. His other assistant surgeon throughout 1863 was James (sometimes John) M. Hawks, but a reference photo of Hawks shows a very different face from the mystery officer. Rogers, in a journal entry, described Hawks as “somewhat older than I,” compared to the younger-looking mystery officer.

Other promising candidates might be 1st Lt. George B. Chamberlain, the regimental quartermaster; or Capt. James Swift Rogers, Maj. Rogers’ nephew and a line officer of the 33rd, but reference photos of both men easily rule them out.

The case for Dewhurst as the mystery officer’s identity is stronger. Maj. Rogers clearly knew Dewhurst well and spent significant time with him. Besides the assistant surgeons Minor and Hawks, Adjutant Dewhurst is one of the most-frequently mentioned officers in Rogers’ wartime journal entries, which are transcribed and posted online by the University of North Florida. For example, Rogers mentions dining with “William and Hattie” (Dewhurst and his wife, who married in February of that year) at the house they occupied outside camp. Thus, it would not be surprising for Rogers to seek a group portrait with two of his closest comrades.

Dewhurst’s age also appears to be a better fit for the mystery officer. Determining his age was surprisingly difficult. I could not find it on any commissioning paperwork or his pension records on Fold3, and his Find-a-Grave memorial page gives his birthdate, burial site, and parentage as unknown. However, I found that the Historical Society of Watertown (Massachusetts) provides a downloadable spreadsheet on their website created by volunteer William McEvoy documenting Civil War veteran burials in nearby Mount Auburn Cemetery. The spreadsheet reveals that Dewhurst died of malaria in Savannah, Ga., just a year after the war’s end. The inscription on his headstone in the cemetery gives his age at death as 27. If Dewhurst is in Rogers’ group portrait, he would be about 24 years old at the time, which looks reasonable, whereas the mutton chopped, balding officer in the solo portrait looks much older. Unfortunately, Dewhurst’s untimely death prevents the possibility of postwar reference photos surfacing to resolve the issue. For now, the Dewhurst ID for the mystery officer is promising, but can’t be confirmed.

Thus, our photo sleuthing adventure has provided some answers and raised new questions. The unidentified young officer in the Library of Congress photo is likely a member of the 33rd USCI, and may very well be the regimental adjutant, George Williams Dewhurst (ca. 1839-1866). The unusual painted backdrop featuring a broken cannon wheel is now known to be associated with several soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts and 33rd USCI, suggesting a link to South Carolina generally and Beaufort in particular. The identity of that photographer remains unknown, but the “CULLYS” inscription painted on the backdrop offers an intriguing clue. More research on both the soldier and backdrop is needed, but each small step brings us closer to solving the mystery.

Special thanks to Ron Coddington, Rich Condon, and Adam Ochs Fleischer for their assistance with this research.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is a MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.