By Frank Jastrzembski

Adventurers from Europe eagerly offered their service to the Lincoln administration in the spring of 1861. Secretary of State William H. Seward sought out “friends of freedom and the American Republic” from overseas, actively encouraging Europeans with military experience to fight for the U.S. government. Seward’s open-arms policy attracted a variety of characters, ranging from the capable to the incompetent. Major General George B. McClellan, no fan of Seward’s call for international aid, observed it “sometimes produced strange results and brought us rare specimens of the class vulgarly known as hard cases,” and most left their own armies for the armies’ good.

Despite McClellan’s distaste for Seward’s policy, many foreigners received commissions in the U.S. Army. There were, however, notable Europeans considered for senior positions as generals, but ultimately did not receive appointments. The stories surrounding these characters are intriguing and unique.

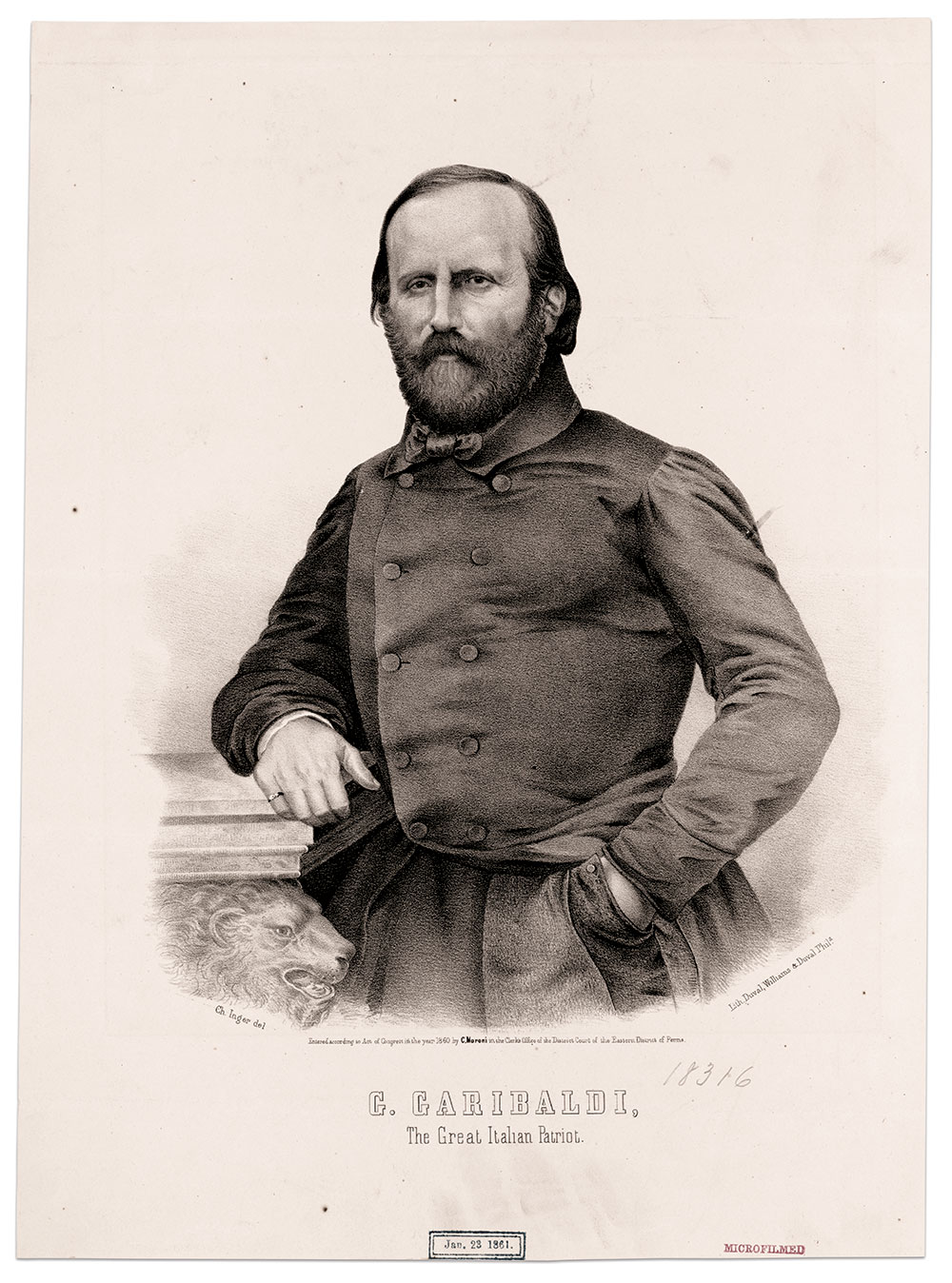

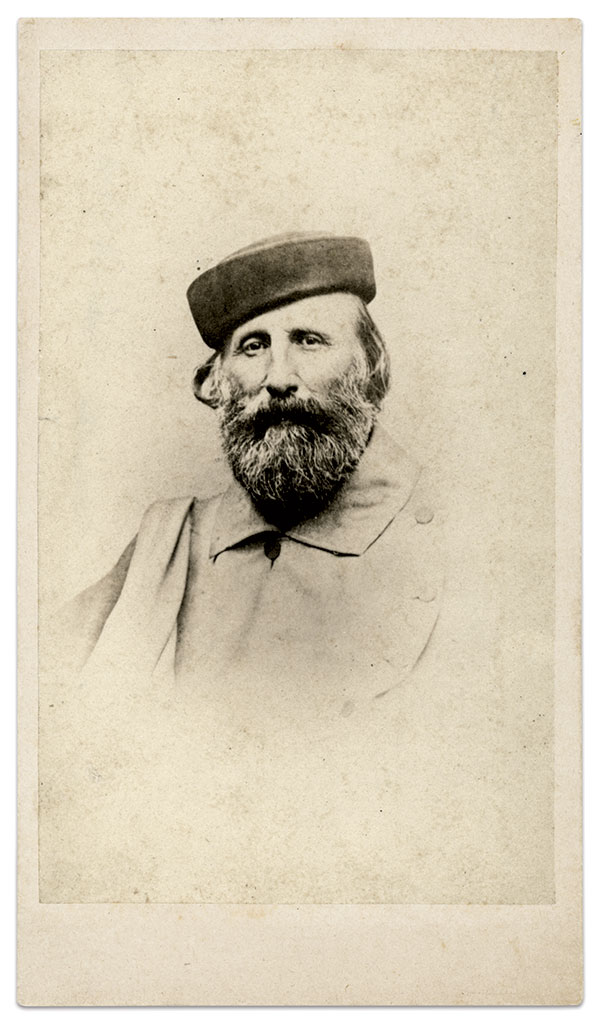

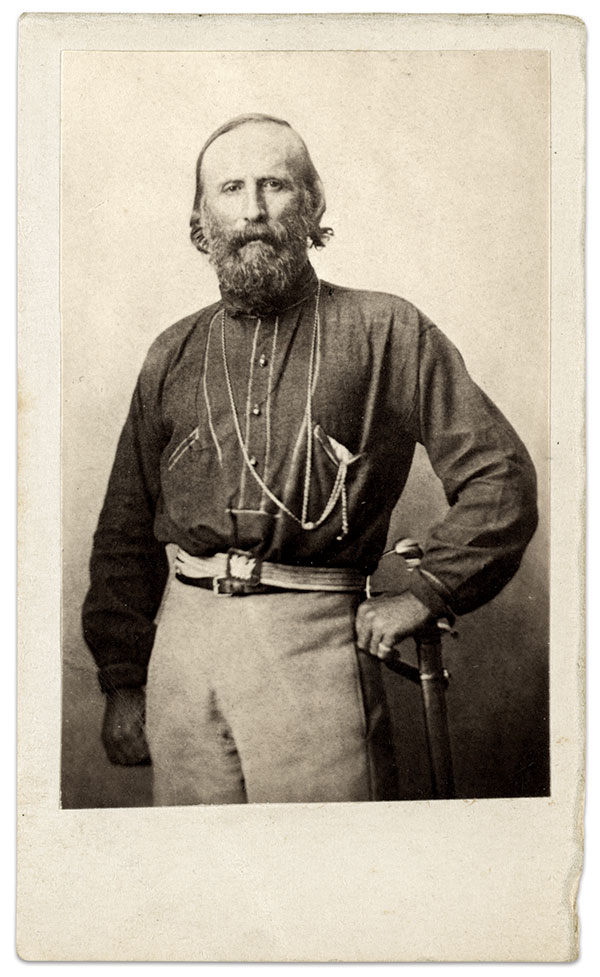

The “Washington of Italy”

The most noteworthy of these was the famous 19th century revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882). The Italian Red Shirts leader was a natural fit to serve in an army fighting to achieve the freedom of others. Besides, Garibaldi had lived in New York during the early 1850s. A rumor circulated that President Abraham Lincoln summoned Garibaldi from his home on the island of Caprera to come to America to aid the war effort.

James W. Quiggle, the American consul to Antwerp, Belgium, initiated contact with Garibaldi. “The papers report that you are going to the United States, to join the army of the North in the conflict of my country,” Quiggle wrote to Garibaldi on June 8, 1861. “If you do, the name of Lafayette will not surpass yours. There are thousands of Italians and Hungarians who will rush to your ranks, and there are thousands and tens of thousands of American citizens who will glory to be under the command of the ‘Washington of Italy.’”

Garibaldi replied to Quiggle’s letter, assuring him that the report that he was headed to America was false, but that he had “a great desire to go.” If the U.S. government thought he could be of some use he would go if invited, as long as he did not find himself occupied in the defense of Italy. The foreign diplomat eagerly forwarded copies of the correspondence to the State Department in Washington, D.C.

While Quiggle had no authority to communicate with Garibaldi on behalf of the U.S. government, Seward found Garibaldi’s remarks intriguing. In July, he sent written instructions to U.S. ministers Henry S. Sanford in Belgium and George P. Marsh in Italy to confidentially meet with Garibaldi and convey the U.S. government’s desire to acquire his service.

“I wish you to proceed at once and enter into communication with the distinguished Soldier of Freedom,” wrote Seward. “Say to him that this government believes his services in its present contest for the unity and liberty of the American People, would be exceedingly useful, and that, therefore, they are earnestly desired and invited.”

Seward stressed to his ministers that the civil war was a fight for “Human Freedom,” and if the U.S. failed, it would be a disastrous blow for not only North America but also the entire world. He promised Garibaldi a major general’s commission, which would “carry with it the command of a large corps d’armée to conduct in his own way within certain limits in the persecution of the war.”

Many might have pounced on Seward’s offer, but not Garibaldi. He wanted more.

Garibaldi felt the only way he could render real service would be as commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army. Also, slavery had to be abolished immediately. In his exchange of letters with Quiggle, the Italian revolutionary asked if the war’s main objective was to emancipate the slaves.

“I say this is not the intention of the Federal Government,” Quiggle replied. “[I]t is to maintain its power and dignity—put down rebellion and insurrection, and restore to the Government her ancient prowess at home and throughout the world. You have lived in the United States; and you must readily have observed what a dreadful calamity it would be to throw at once upon that country in looseness, four millions of slaves.”

For Garibaldi, overall command of the U.S. Army and the immediate emancipation of the slaves were nonnegotiable demands.

“He would be of little use, he said, without the first,” Sanford wrote to Seward after meeting with Garibaldi at his home on Caprera. Without the second, Garibaldi explained, “the war would appear to be like any civil war in which the world at large could have little interest or sympathy.” For Garibaldi, overall command of the U.S. Army and the immediate emancipation of the slaves were nonnegotiable demands. Sanford had no authority to promise either, so he departed Caprera without securing Garibaldi’s service.

Despite a continued interest by both parties into the fall of 1862, the marriage between Garibaldi and the Lincoln administration was not meant to be. Certainly, Garibaldi would have stolen the spotlight had he come to America to take command of a corps or been given an independent command. Lincoln eventually did emancipate the slaves on Jan. 1, 1863, but it was two years too late to acquire the services of Garibaldi. Upon hearing this news, Garibaldi and his sons, Menotti and Ricciotti Garibaldi, sent a letter to Lincoln in August praising the president as the “Emancipator of the Slaves in the American Republic,” and extolling him for restoring an entire race of mankind to “the dignity of Manhood, to civilization, and to Love.”

The exiled Hungarian general

While he may not have had the same level of notoriety as Garibaldi, Hungarian revolutionary György Klapka (1820-1892) had arguably as hefty an asking price as the Italian revolutionary.

Klapka had risen through the ranks of the Austrian Army but in 1848 joined the rebellious Hungarian government to help it break free of the Habsburg yoke. Klapka made a name for himself during the war of independence, most notably for his defense of the fortress of Komárom (Comorn). After the Hungarian revolution crumbled, Gen. Klapka fled and lived in exile in England and Switzerland.

Naturally, his name came up as a possible candidate for a general’s commission in the U.S. Army, especially with the lack of able generals at the senior level during the early part of the war.

On Sep. 20, 1862, after the defeat at Second Bull Run, The Spectator in London criticized Lincoln for not sending for an illustrious European general such as Klapka to replace Maj. Gen. John Pope if no subordinate U.S. general was up to the task.

In his memoirs, McClellan recalled receiving a letter from Klapka informing him that Seward’s agents had contacted him. Klapka thought it was best to discuss his terms with McClellan first. He reportedly requested a regular salary of $25,000 plus a bonus of $100,000 in cash. To put this into better context, the monthly salary for a U.S. major general during the Civil War was $457. Klapka demanded a salary equal to President Lincoln’s yearly pay.

Klapka demanded a salary equal to President Lincoln, and chief of staff to McClellan until he could replace him as commander of the Army of the Potomac.

But there was more. Klapka didn’t speak English, so he planned to act as McClellan’s chief of staff until he was fluent enough to take McClellan’s place as head of the Army of the Potomac.

“He failed to state what provision he would make for me,” a perturbed McClellan wrote. “[T]hat probably to depend upon the impression I made upon him.”

McClellan took Klapka’s letter to Lincoln, which he claimed angered the president. Lincoln reportedly assured McClellan “that he would see that I should not be troubled in that way again.” If true, it was one of the rare instances during the war that McClellan and Lincoln agreed.

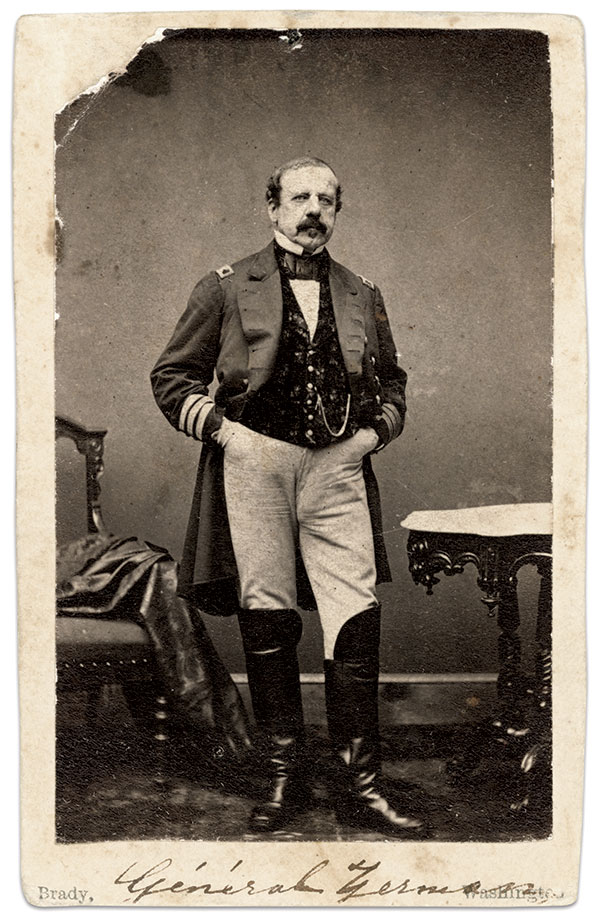

The enigmatic admiral

It is hard to separate fact from fiction when it comes to Jean Napoleon Zerman (1790-1876). In 1874, the San Francisco Evening Bulletin reported that he received the Legion of Honor from Napoleon for his service defending a bridge at the Battle of Waterloo, and that he participated in Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott’s campaign to capture Mexico City during the Mexican War. It also claimed that he fought under Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell at Bull Run, and was wounded in both legs during the capture of Richmond, Va., in 1865.

All these incidents were fabricated, but made for a good story.

What we do know is that he was born Giovanni, in Venice, Italy, and likely fought in the French Navy. The Austrians arrested Zerman and sentenced him to death in 1833 for attempting to overthrow their rule in Italy. They commuted his sentence and imprisoned him at Špilberk Castle. He switched sides and, in 1842, worked as a secret agent for the Austrian chancellor. He eventually left for the U.S., settled in San Francisco, and operated a ship ballast business.

Dissidents of Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna approached and recruited Zerman to overthrow his rule in Baja California. In 1855, Zerman left San Francisco aboard the bark Archibald Gracie. He designed an outlandish uniform that would have made George Armstrong Custer envious: It combined a Mexican and English naval officer’s formal dress and included a sombrero with two chicken feathers jutting out of it.

When he landed at La Paz, Mexican military governor Gen. José María Blancarte arrested him. Zerman claimed that due to the stress and violent trip they made, his wife, Marie, aborted at six months. He was tried as a filibuster for being engaged in unauthorized military operations, but the Mexican Supreme Court acquitted him. He returned to the States after a roughly two-year imprisonment.

In August 1861, Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont appointed Zerman to his colorful staff, composed of many foreign soldiers. Newspapers reported that the Pathfinder wanted him to command a Mississippi flotilla. Later, Zerman served as Maj. Gen. David Hunter’s inspector general with the rank of colonel, but apparently served in a volunteer capacity without an official commission.

On Dec. 22, 1861, President Lincoln recommended Zerman be appointed a brigadier general in place of his friend and former lieutenant governor of Illinois, Gustavus Koerner, who turned down the appointment.

In February 1862, Zerman expressed his pleasure in a letter to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. “I am very anxious to enter immediately into active service in the vanguard of the Army,” he wrote, “where I am confident of rendering essential service.”

On March 15, President Lincoln nominated Zerman as a brigadier general of volunteers.

Detractors branded Zerman a charlatan and tried to halt his promotion. French ambassador Henri Mercier claimed he was “a convicted swindler and forger, who has served in galleys and pined in the jails of Europe so often, that such facts ceased to be novelties worth mentioning.” The French consulate had not forgotten that in 1850, Zerman attacked its general, Félix Lacoste.

“I am curious to know who recommended this person to the confidence of the President—he must be either a deluded fool or a confirmed knave,” Commodore Charles Henry Davis wrote to Seward on April 2. “If the report of this nomination is an error—then I have no more to say regarding this Vagrant—but if otherwise you will not fail to see the importance of preventing a very bad egg from going into the great national pudding.”

Major Gen. Henry W. Halleck, distrustful of foreigners, snubbed Zerman when he arrived in St. Louis with letters of recommendation from Lincoln and others, and requested a position as inspector general on his staff. “Having known his history for many years, and being familiar with his swindling transactions in Mexico, New York and San Francisco,” Halleck told Brig. Gen. Seth Williams, Adjutant General of the U.S. Army, in a letter, “I declined having anything to do with him.” Halleck said that he heard reports that Zerman went about town for several days afterward criticizing him, especially to the Germans, and then disappeared.

I am curious to know who recommended this person to the confidence of the President—he must be either a deluded fool or a confirmed knave.

— Commodore Charles Henry Davis

But the enigmatic officer had an equal amount of allies in his corner. Brigadier General James Cooper wrote to President Lincoln on March 21, telling the president that he had known Zerman for several years. General Angel Trías Álvarez and several other distinguished Mexican politicians gave him the impression that Zerman was “as an able and upright man, possessing great activity, energy and prudence.”

On April 7, 38 individuals signed and sent a letter to New York Senator Ira Harris defending Zerman’s character. They attested that he was a true gentleman and valiant soldier, who gained glory fighting for liberal and republican principles. “Because General Zerman has been for a long time our countryman, and that in our present circumstances we need soldiers of experience,” it read, “we hope again that His Excellency our President will grant him his protection, and our Senate his nomination.”

Major Gen. David Hunter even wrote Lincoln requesting that Zerman report to him for duty if appointed.

The Senate confirmed Zerman’s nomination on May 5, but the damage had already been done. The Senate recalled his nomination the following day.

Senator Harris wrote to Lincoln urging him to intervene. “I feel great sympathy for the General—I am sure he is a worthy and competent man,” Harris assured him. “He has great experience and would I am sure render very valuable services to General Hunter in his present position—He has every incentive to distinguish himself and I am sure he would do it.”

Harris’ last-ditch effort failed. Congress withdrew Zerman’s nomination on June 18.

Zerman did not surrender so easily. In July, he wrote to Peter Grayson Washington, the former assistant secretary of the treasury, asking him to go to Harris to inquire if Hunter had received any word regarding his promotion.

On August 14, Zerman penned a letter to Lincoln. “In the month of March you appointed me Brigadier General in May the Senate confirmed that appointment but the intrigue of foreign politicians caused a reconsideration which was Decided against me,” he declared. “Know with the draft you need good officers therefore Excellence I hope you will employ a man who has forty years of experience in the military career and who is disposed to sacrifice his life for our cause and whose Services will be satisfactory to your opinion.”

Despite his strongly worded letter, Zerman never obtained the appointment he so badly sought. He died in obscurity in San Francisco in 1876 and is buried in an unmarked grave in Colma, Calif., with his wife and granddaughter.

Differing motives, same cause

Had Garibaldi, Klapka, or Zerman been granted a general’s commission, it is probable that they would have played significant roles in the war, potentially impacting its outcome in either positive or negative ways. The arrival of Garibaldi or Klapka on American soil would have caused a sensation due to their notoriety. While Zerman’s reputation dwarfed Garibaldi’s or Klapka’s, he was the closest of the three to obtain a general’s commission. Considering his extensive military and naval background, which, although some parts were fabricated, could have potentially been valuable in the Western Theater. It is possible that his actions in such a role could have supported the claims made by his critics and opponents.

There were numerous Europeans with prior military experience that did serve as generals or officers in the U.S. Army during the Civil War. Their motivations for serving varied, ranging from protecting their newly adopted country, defending specific ideologies or causes, or seeking personal recognition and glory—or a combination of these factors. Their levels of success varied, and some lost their lives fighting to defend the U.S. Regardless of their motivations, they played a part in shaping America’s history.

Note: The author started a GoFundMe campaign to place a headstone on Zerman’s unmarked grave at Holy Cross Cemetery in Colma, Calif. You can help fund the project by donating here: https://www.gofundme.com/f/jean-napoleon-zerman-headstone-fund. You can follow the author’s other grave projects by visiting his Facebook page Shrouded Veterans.

References: Seward, Seward at Washington as Senator and Secretary of State: A Memoir of His Life, with Selections from His Letters, 1846-1861; McClellan, McClellan’s Own Story; Mitgang, “Garibaldi and Lincoln,” American Heritage 26, No. 6 (October 1975); Marraro, “Lincoln’s Offer of a Command to Garibaldi: Further Light on a Disputed Point of History,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 36, No. 3 (September 1943); Gay, “Lincoln’s Offer of a Command to Garibaldi: Light on a Disputed Point of History,” The Century Magazine 75, No. 1 (November 1907); Giuseppe Garibaldi, Menotti Garibaldi, and Ricciotti Garibaldi to Abraham Lincoln, Aug. 6, 1863; Sanders, ed., Celebrities of the Century: Being a Dictionary of Men and Women of the Nineteenth Century; The Spectator, London, England, Sept. 20, 1862; Daily Evening Bulletin, San Francisco, Calif., July 18, 1874; Arkansas Times and Advocate, Little Rock, Ark., May 23, 1842; Daily Missouri Republican, St. Louis, Mo., July 3, 1850; Stout, Schemers and Dreamers: Filibustering in Mexico, 1848-1921; Chamberlin, “Baja California After Walker: The Zerman Enterprise,” The Hispanic American Historical Review 34, no. 2 (May 1954); Zerman, Manifestación Que Hace a Todas Las Naciones Con Especialidad a la República Mexicana; James Cooper to Simon Cameron, Sept. 17, 1861; Jean Napoleon Zerman to Abraham Lincoln, Nov. 8, 1861; Henry W. Halleck to Seth Williams, Feb. 6, 1862; Jean Napoleon Zerman to Edwin M. Stanton, Feb. 7, 1862; Jean Napoleon Zerman to Lorenzo Thomas, March 4, 1862; David Hunter to Abraham Lincoln, March 14, 1862; James Cooper to Abraham Lincoln, March 21, 1862; Charles H. Davis to William H. Seward, April 2, 1862; Jean Napoleon Zerman to the Senate, June 2, 1862; Ira Harris to Abraham Lincoln, June 13, 1862; Jean Napoleon Zerman to Abraham Lincoln, Aug. 14, 1862; The Evening Post, New York City, May 31, 1862; The Ashland Union, Ashland, Ohio, June 11, 1862; Columbian Register, New Haven, Conn., May 17, 1862; Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America, From December 2, 1861, to July 17, 1862, Vol. 12.

Frank Jastrzembski studied history at John Carroll University and Cleveland State University. He’s written dozens of articles for journals, magazines, and blogs. He’s currently working on book projects about the emotional experiences of Civil War generals during the U.S.-Mexican War and his headstone projects. Jastrzembski also has a quarterly column in America’s Civil War. He runs “Shrouded Veterans,” a nonprofit mission to rescue the neglected graves of 19th-century veterans, primarily Mexican War and Civil War soldiers, by identifying, marking, and restoring them.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.