By Marcy E. Zimmer

Sometimes a face reveals a hidden story. At first glance, this portrait of an older gentleman and his wife leaves an impression of a simple and domestic couple. Upon closer inspection, however, one might notice how the gentleman’s thick mustache seems uneven compared to the patchy beard.

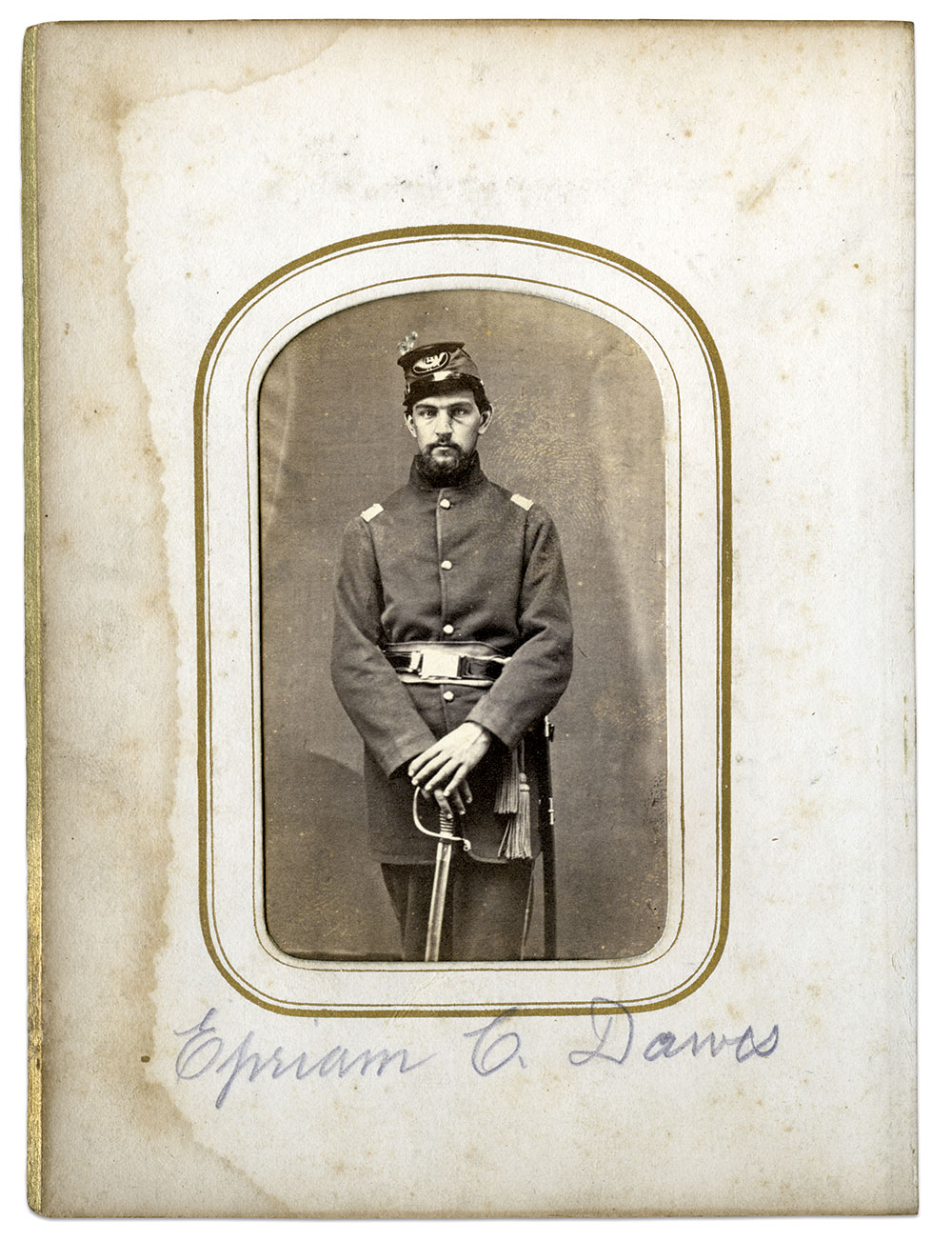

Hidden beneath the facial hair lays the story of a wounded Civil War veteran; one Ephraim Cutler “Eph” Dawes, late major of the 53rd Ohio Infantry. The account of his wounding and suffering is representative of those soldiers on both sides of the conflict who received disfiguring wounds in battle.

On May 28, 1864, the day after Eph’s 24th birthday, he and his regiment fought in the Battle of Dallas, part of the Atlanta Campaign. Eph recounted his wounding in letters to his family. “We were in rifle-pits, the rebels charged us. I was standing up with our color company, & turned to go to the right a moment, got shot. The rebels came within twenty feet of us. We whipped them shamelessly.”

Eph also described the nature of the wound, recalling, “A minié ball entered the left side of my lower jaw—out the right—carrying away the lower of my chin and most of my lower teeth and badly leaving the flesh and lip.” Bleeding profusely, the young major made his way to the relative safety of a wooded area and crawled on his hands and knees to the rear for treatment. Gasping for air on all fours, he almost suffocated from the blood. Somehow he made it.

Thus began a long road to recovery and adjusting to life with a very visible war wound, and less obvious mental scars.

The first step in his healing required an arduous 140-mile journey back north to Cincinnati to receive medical attention. Eph recalled it as “a trip that I shall always look back to with horror.”

On the first leg, Eph felt as though he was “tortured nearly to death”; there was no cessation of this feeling as he bumped along roads in a wagon. Reactions from those with whom he came in contact added to his woes. Everett H. Rexford of the 1st Illinois Artillery observed Eph in the wagon “sitting with his back to others so not to show his ghastly wound.” At Kingston, Ga., a woman brought him a bowl of soup. Ephraim wrote, “I took off my bandage to drink it. She looked at me, burst into tears, and ran away.” A surgeon who came to dress the wound “turned very white and went away” at the sight of his face.

There were other problems. Swallowing became nearly impossible and overly painful. Reduced to spoonfuls of water at a time, medical personnel limited his diet to soft foods such as blueberries, oysters, eggs, soups and any liquids. In addition, he could barely talk, a misery that challenged Eph from communicating his needs.

These chilling encounters and physical challenges most likely increased Eph’s eagerness to get his face restored. Luckily, he received assistance from Dr. George C. Blackman, whom Eph described as “the finest surgeon in the U.S.”

Eph was right. Blackman, educated at Yale and the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, served as professor of surgery at the Medical College of Ohio in Cincinnati when the war began in 1861. That same year, he and U.S. Army Surgeon Charles Tripler co-authored Hand-Book for the Military Surgeon.

It is easy to miss the stories hidden behind a beard or under a coat. It is an absolute necessity that every viewer should take the effort and time to fully examine a photo—and not miss history.

Blackman had full confidence in his ability to help. He wrote to Eph’s mother, “the deformity resulting from the wound of your son’s face can be almost entirely removed.” Blackman performed the operation on Sept. 22, 1864, and invited fellow surgeons to observe the procedure.

Meanwhile, Eph held little confidence that he would ever have a jaw again. Blackman, however, exceeded his expectations by providing him with a sort of jaw and lower lip by cutting strips of flesh from Eph’s cheeks and pulling them tightly over the jawline and lip to provide skin. After stitching the flesh in, temporary steel pins were added to provide additional support.

Blackman and the attending surgeons understood the operation would be extraordinarily painful. One surgeon told Eph’s brother, Lt. Col. Rufus R. Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry, “that a man who could endorse what Major Dawes had that day would bear burning at the stake.” Observers were amazed at Eph’s self-possession and his ability to obey every direction of the surgeon “until the pain and loss of blood exhausted him,” wrote one witness. After the operation, Blackman decided Eph needed two more stitches. In a somewhat humorous yet desperate response, Eph “held up [his] finger for one but unavailingly.” These stitches were recorded by Eph to have “hurt worse than all the rest.”

When the patient sat up from the painful operation, someone suggested bringing him a looking glass, to which a member of the crowd responded, “‘No no don’t bring it.’” If Eph heard the comment, it must have caused him to feel uncertain about the result. When Eph finally did take a first glimpse in the mirror, he remembered thinking of the steel pins, “it looks just like a turkey made ready for roasting.” Yet, the operation proved satisfactory enough for Eph, who summed up the surgery as “horrible torture but the end justified the means.”

The healing process was slow. Eph did not call on or meet with friends out of fear that progress would be disrupted. He lived with his stitches and steel pins for a few days and waited a long six weeks to receive his full set of false teeth.

Eph’s family, especially his sister Lucy, remained deeply concerned. Blackman reassured her that Eph’s face “will look for a while as if he’s been under the Drs hands,” but would surely look better soon. It did improve, prompting Lucy to note, “Eph looks more like himself.” And Eph acted more like himself, teaching Lucy how to play billiards—a positive mental sign.

Though the psychological impacts of Eph’s wound and its aftermath cannot be measured with precision, his correspondence suggests his feelings were contradictory. Sometimes, he struck a melancholy chord, and affirmed a more philosophical approach to life, vowing, “to quit smoking and singing and whistling and all such frivolous amusements.” He seemed disinterested in war news. Yet, he longed to be back in the military and contribute to defeating the enemy. Two years after his wounding, he married Frances Martha “Fanny” Bosworth. Despite the joy he found in love, Eph’s melancholia was real. The mixed emotions he demonstrated reflected the cost of military service on the human psyche.

Eph hid the price he paid for defending his country under facial hair. One writer observed that Eph had grown “a full beard, and, it is said, became a fine-looking man.” If a casual viewer, with no prior knowledge of Eph, saw photos of him before and after his wounding, it is plausible that they would assume he simply got older and grew a beard. They would likely have never guessed he had his entire jaw shot away in battle and endured painful reconstructive surgery.

Eph became successful in business and owner of one of the largest mining companies in Illinois. He maintained an active interest in the Civil War, collecting manuscripts, books and other primary sources. He lectured on the war, contributed to the Battles and Leaders of the Civil War series, and wrote articles and books. He died in 1895 at age 54 from heart disease. Fanny lived until 1925. They had no children.

It is easy to miss the stories hidden behind a beard or under a coat. It is an absolute necessity that every viewer should take the effort and time to fully examine a photo—and not miss history.

References: Ephraim C. Dawes papers, The Newberry Library, Chicago; Magnusen, Steve. “Outside of a Famous Brother’s Shadow,” Aug. 17, 2022, Kenosha Civil War Museum, Kenosha, Wis., youtube.com/watch?v=_a6A0jy6C9o; Dawes, Service with the Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers: Four Years with the Iron Brigade, Cottrell, Jeffrey, “Major Ephraim Cutler Dawes.” sites.google.com/a/kent.edu/glh2017/jeffreycott/major-ephraim-cutler-dawes

Marcy Zimmer begins her freshman year at Gettysburg College in the fall. She studies Civil War era military history and loves all things history related. Her favorite subject to study is the Army of the Potomac and its many campaigns. She aspires to take her passion for history onto the battlefield and become a licensed National Park Service battlefield guide. Her dream is to work at Antietam National Battlefield and author books about Civil War history. Marcy may be contacted at zimmer.marcy@gmail.com.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.