By Joe Bauman and Ronald S. Coddington

British warships and transports anchored off New Haven, a key port in the colony of Connecticut, on July 4, 1779. Aboard the vessels about 2,000 sailors and 3,000 troops awaited orders from the fleet’s commander, Maj. Gen. William Tryon, the royal governor of New York.

Tryon turned the soldiers loose that evening. Under cover of darkness, the men ransacked, looted and burned homes in New Haven, killing and wounding 38 citizens, and carrying off a dozen more as prisoners of war. Loyalists dissuaded the British from torching the entire town, but two nearby Connecticut communities, Norwalk and Fairfield, were not as fortunate.

After the invaders returned to the fleet for the voyage back to New York City, a physician and his son set to work to save New Haven’s injured. Doctor Eneas Munson and his 15-year-old son and namesake, Eneas, were no strangers to the brutality of the enemy. A few years earlier, the British had hanged a family friend, Nathan Hale, as a spy.

The Raid on New Haven proved a grim training exercise for young Munson. He was in the middle of the medical program at the local university, Yale, and studied under his father.

The following year, on Sept. 1, 1780, now 16-year-old Munson volunteered for the Revolutionary Army. He received a commission as surgeon’s mate, assistant to the surgeon in Connecticut’s Seventh Regiment of the Continental Line. Less than two weeks later, he celebrated his 17th birthday and graduated from Yale.

Armed with a medical degree and his experience treating wounded, Munson embarked on a military career and participated in the war’s momentous final campaign.

Early actions in Washington’s army

Munson’s first recorded service as surgeon’s mate occurred after a raid by the American Army and its French allies on Jan. 22, 1781, at Morrisania, N.Y. (Today the town site is in the South Bronx.) American and French forces attacked the headquarters of Col. James DeLancey, a pro-British man known as the “Outlaw of the Bronx.” He commanded the Refugee Corps, a group of displaced loyalists.

A stiff battle ensued. The pro-American Pennsylvania Gazette and Weekly Advertiser declared it a victory, noting light casualties, destruction of the Corps’ barracks and forage, burning of a bridge, and capture of 52 prisoners, horses and cattle.

Munson treated wounded soldiers on the battlefield. Long after the war, he shared his recollections of that day with his own son, Charles, who explained, “My father was the only surgeon. The latter represented his own service as lively and perilous—that he was kept busy in dressing wounds and extracting bullets in the open field under exposure to the enemy’s fire till Capt. [Henry] Daggett, discovering him, rode up in great excitement, and shouted—‘Dr. Munson, who put you there? You are the only surgeon on the field, and we may all be in your hands yet. Move instantly to a position beyond yonder large rock.’ ‘I was quite willing,’ said my father, ‘for the change and took the position quick time. The wonder was that the bullets did not take me quicker than I could take the shelter.’ He added—‘I extracted sixty bullets during that skirmish.’”

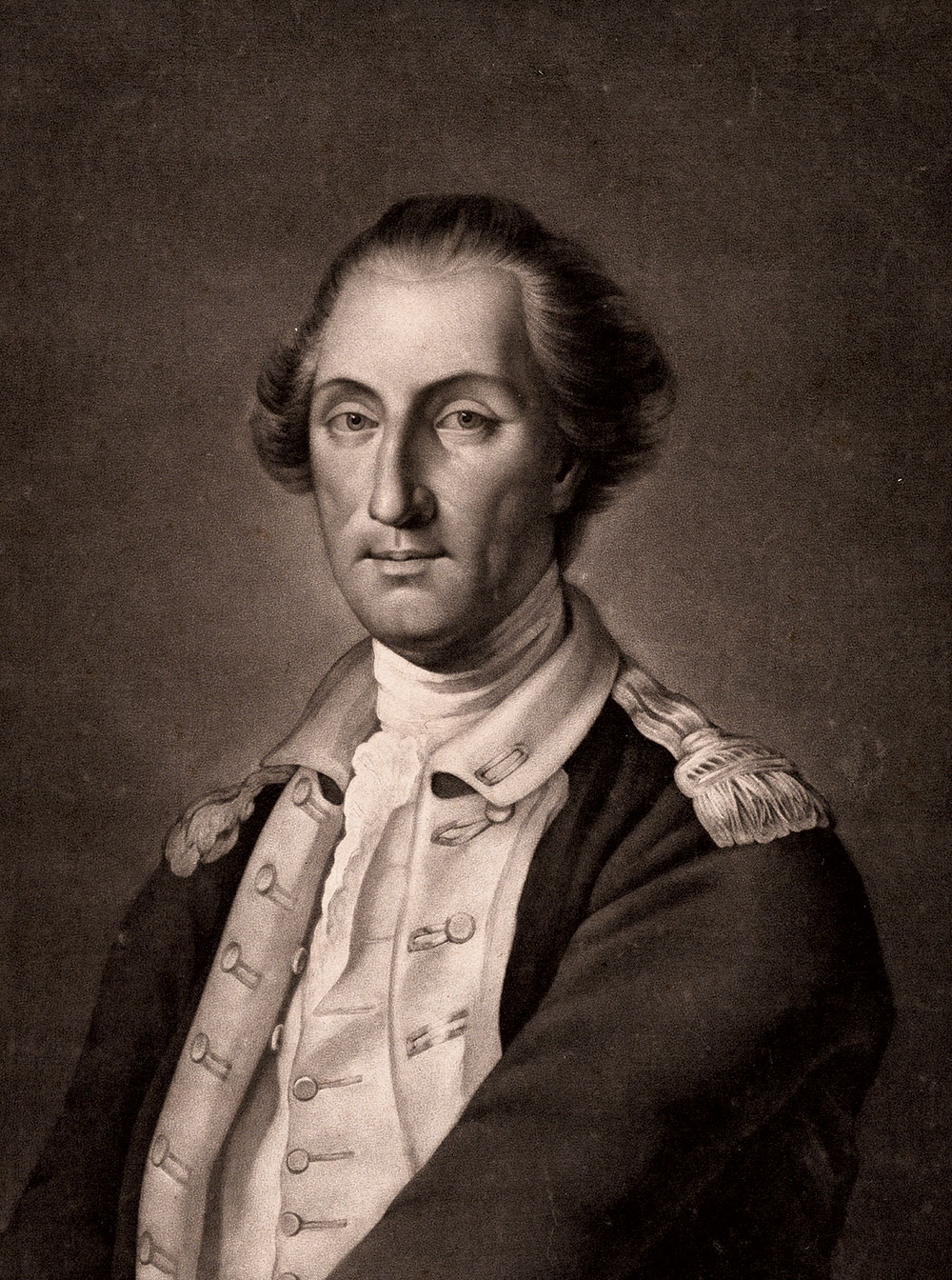

In mid-July 1781, Munson embarked on a new assignment with an elite corps of light infantry composed of the best soldiers from several New England regiments. The commander of the force, Col. Alexander Scammell, enjoyed a sterling reputation. Massachusetts born and Harvard educated, he had proved an able soldier with two New Hampshire regiments. He crossed the Delaware with Washington’s Army in 1776 and proved his mettle in combat at the 1777 Battle of Saratoga, considered by many historians as the Revolution’s turning point. Scammell’s medical staff included Dr. James Thatcher as surgeon and Munson as surgeon’s mate. Records suggest the army’s chief surgeon, Dr. James Craig, had appointed them.

With the Light Infantry Corps at Yorktown, 1781

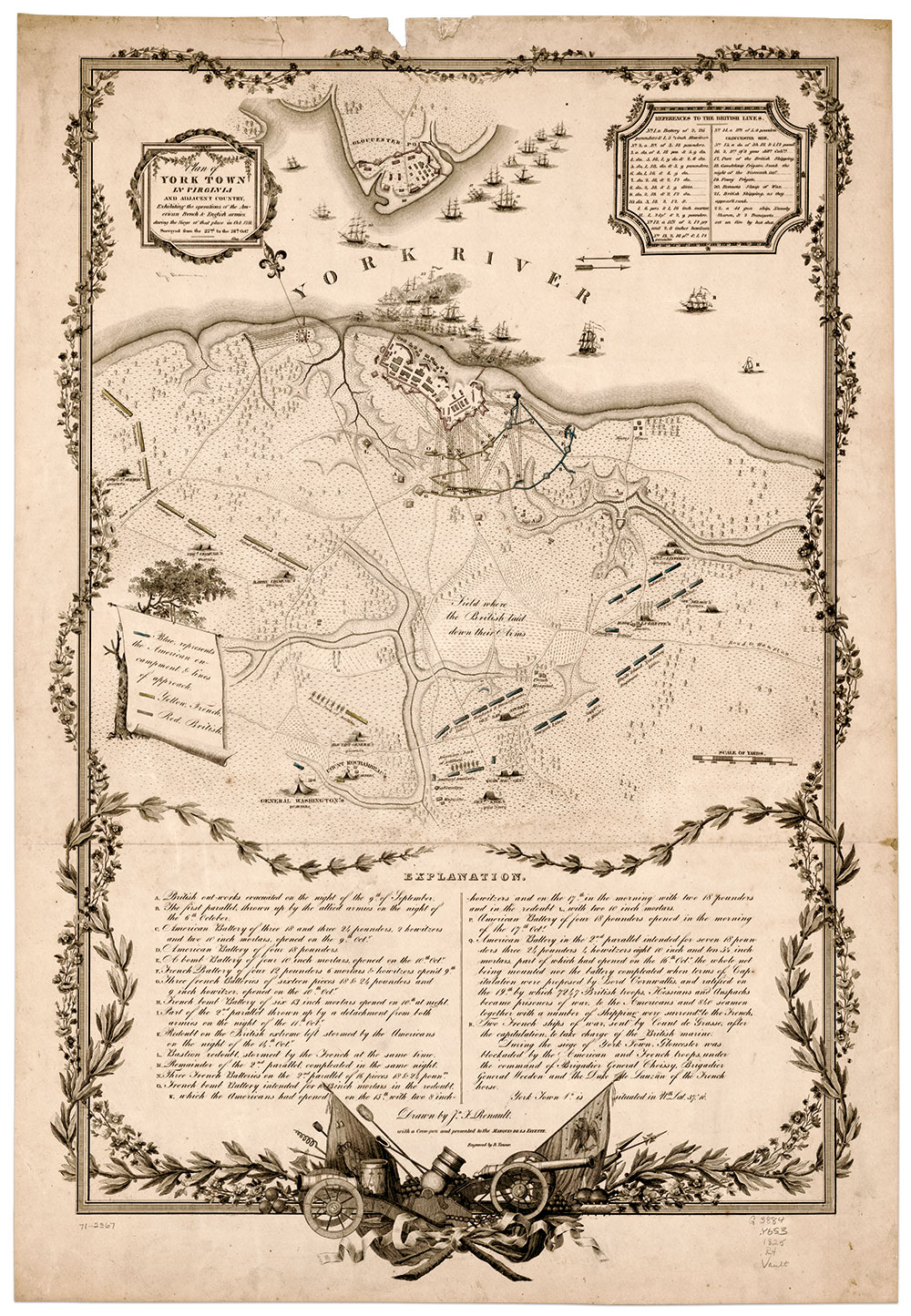

Four hundred miles south in Virginia, about 8,000 British soldiers led by Lord Charles Cornwallis found themselves in a precarious position at Yorktown. The troops had dug in along the York River, west of its mouth along the Chesapeake Bay. A smaller force of Americans commanded by Washington’s former aide, the Marquis de Lafayette, blocked them by land. Cornwallis had two possible ways out: Use his superior numbers to break the enemy lines by land, or be extracted by British vessels via the Chesapeake.

Washington and his French partners glimpsed a golden opportunity. If French warships blockaded the Chesapeake, and enough troops could be shifted south to link up with Lafayette, they could besiege Cornwallis and bag his army.

Washington assembled a strike force of 2,000 Continentals and 4,000 French. The American contingent included 1,400-strong Scammell’s Light Infantry. Surgeon Thatcher and Mate Munson belonged to a battalion commanded by a promising young officer, Alexander Hamilton.

The strike force marched hundreds of miles south and joined Lafayette’s troops, swelling the allied army to more than twice the enemy’s total. On September 5, French frigates defeated the British Navy at the Battle of the Chesapeake and sailed into the bay.

The allies trapped Cornwallis in the defenses of Yorktown. The British garrison had constructed a double line of earthworks armed with 65 cannon. The artillery opened up as allied ground troops moved closer. The siege was on.

Munson bore witness to the fighting and shared his recollections after the war.

In a vivid account of a French cavalry charge, relayed to his son Charles, Munson did not note the date or name the opposing forces. It is likely that he observed the October 3 clash between a French cavalry unit, the legion of the Duc de Lauzun, and British cavalry commanded by Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton at Gloucester Point along the York River opposite Yorktown.

“At length the French general gives the command, and gives it with a will. In my father’s imitation, the word was ‘sharze.’ His representation of the scene was exciting. Every movement of man and horse, every yell of command, every flashing saber—everything was something to him, for all of it he felt, and part of it he was. The French general calling out to his troops—distinguished them by their military title, in French—loud and long drawn out, articulate and emphatic, and rising to a marvelous peroration upon the word charge, repeating it over and over, till it had risen into a perfect scream (such a scream!)—‘Sharze, sharze! SHARZE!!’—its last utterance yet louder and longer till it seemed to lose and to overtake again, its own echoes, while riders and horses equally electrified, flew to the conflict as on wings of the wind—the whirlwind.”

On October 14, the allies launched a nighttime attack against two earthen forts, Redoubts No. 9 and 10, located about 300 yards from the main British defenses. Hamilton and his light infantrymen stormed No. 10 as French soldiers under Baron de Vioménil hit Redoubt No. 9. They captured both forts after heavy fighting.

In the immediate aftermath of victory, about 400 American soldiers occupied Redoubt No. 9. Among the protective blinds of large casks and barrels filled with sand stood Hamilton and artillery chief Gen. Henry Knox. Munson was also present, a few paces from the senior officers.

Washington had given the men strict instructions regarding incoming British artillery fire. If solid shot, he forbade the soldiers from yelling an alarm because it would hit before anyone could get out of the way. If an explosive shell with a delayed fuse, warnings were encouraged to enable men to get out of the way before it detonated.

Munson overheard Hamilton and Knox arguing. Hamilton said it seemed un-soldierly for a man to holler, “A shell!” while Knox said Washington’s order was wise.

Munson recalled, “The argument, thus stated, was progressing with a slight degree of warmth, when suddenly spat! spat! two shells fell and struck within the redoubt. Instantly the cry broke out on all sides, ‘A shell! a shell!’ and such a scrambling and jumping to reach the blinds and get behind them for defence. Knox and Hamilton were united in action, however differing in words, for both got behind the blinds, and Hamilton, to be yet more secure, held on behind Knox, (Knox being a very large man, and Hamilton a small man.) Upon this Knox struggled to throw Hamilton off, and in the effort himself (Knox) rolled over and threw Hamilton off towards the shells. Hamilton, however, scrabbled back again behind the blinds. All this was done rapidly, for in two minutes the shells burst, and threw their deadly missiles in all directions. It was now safe and soldier-like to stand out. ‘Now,’ says Knox, ‘now what do you think, Mr. Hamilton, about crying shell?—but let me tell you not to make a breastwork of me again.’ Doctor Munson added, that on looking around and finding not a man hurt out of the more than 400, Knox exclaimed, “It is a miracle!”

Munson added that after the capture, Washington turned to Knox and said, “The work is done, and well done,” and then called to his slave-servant, “Billy, hand me my horse.”

The fall of the redoubts hastened the end of the siege. Allied artillery batteries pounded British defenses at a range of less than 300 yards. “The whole peninsula trembles under the incessant thunderings of our infernal machines; we have leveled some of their works in ruins, and silenced their guns; they have almost ceased firing,” Surg. Thatcher wrote.

Less than two days later on October 17, Cornwallis raised the white flag. Munson witnessed the surrender, ending the war, and leading to British recognition of American independence.

In the Light Infantry Corps, the joy of the surrender was tempered by the loss of its leader. On the morning of September 30, Col. Scammell, acting as officer of the day, reconnoitered an abandoned section of the outer defenses of Yorktown. A detachment of enemy horsemen discovered the movement and demanded his surrender. According to Surg. Thatcher, after taking Scammell into custody “they had the baseness to inflict a wound which we fear will prove mortal; they have carried him into Yorktown.”

Washington petitioned Cornwallis to release the wounded colonel, and the enemy commander paroled Scammell to the hospital at nearby Williamsburg. There, Munson was the first surgeon to treat the beloved officer. In an interview with historian Benson J. Lossing, Munson explained, “I probed the wound but could not find the ball.” He added that he “was in constant attendance upon him after he was fatally wounded until his death” three days later.

Epilogue

After the Revolution, Munson returned to New Haven, took charge of a smallpox hospital and became involved with county and state medical societies. He went into private practice with limited success. By the 1790s, he turned his attention to more lucrative business opportunities, including insuring whaling voyages, commercial real estate and money lending. He helped finance a groundbreaking project to mass-produce firearms by Eli Whitney.

Munson earned a sterling reputation for being punctual and discreet in his shrewd business dealings. A well-dressed gentleman of impeccable manners, he enjoyed playing cards and a good story. The latter trait, and his longevity, attracted the attention of historians working during the first half of the 19th century to preserve personal accounts of those who participated in the Revolution. Munson’s recollections are scattered across several books published in the years leading up to the Civil War.

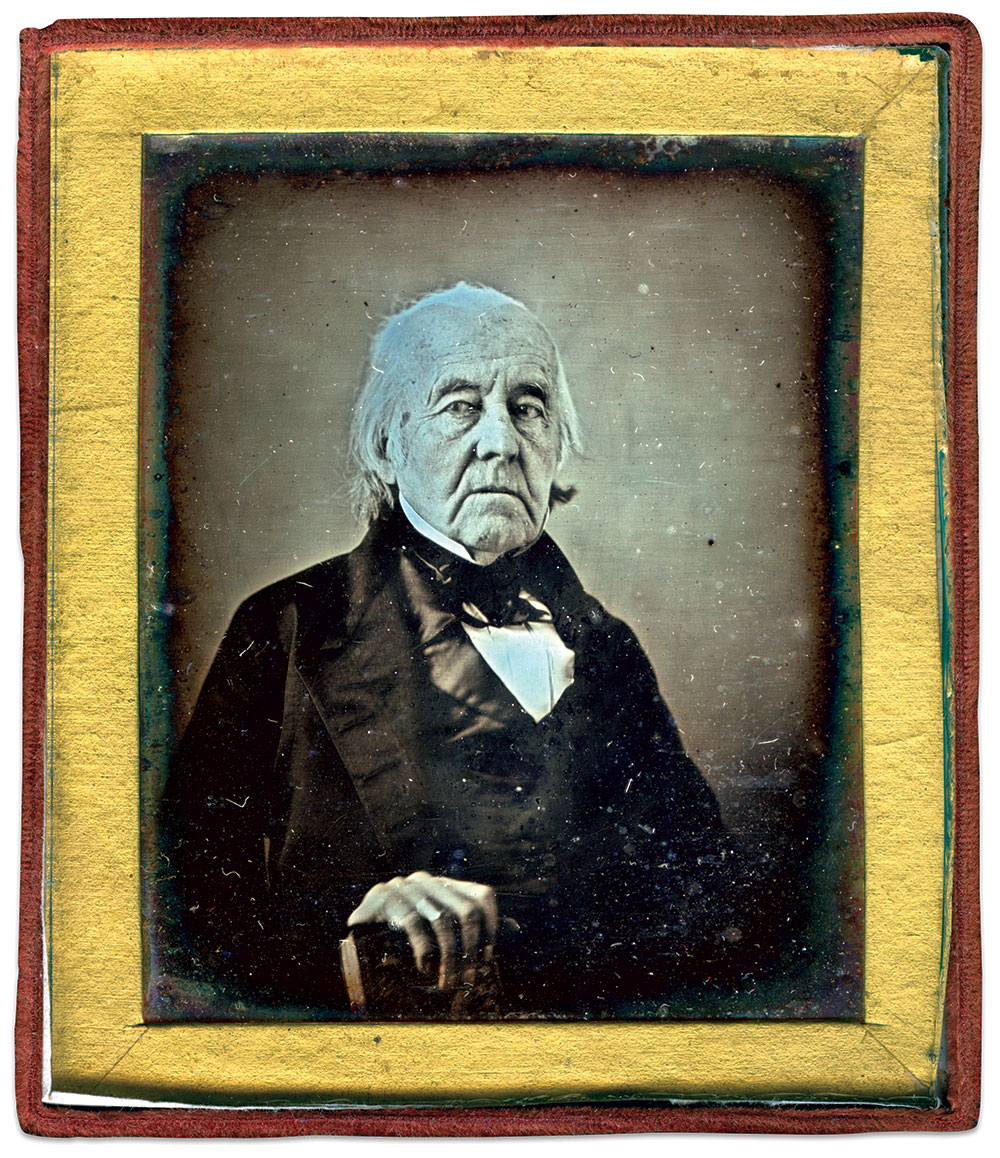

Dysentery took Munson’s life at 9 p.m., Aug. 22, 1852, when he was almost 89 years old. He had lived to see the first 13 presidents of the United States, from George Washington, whom who stood near at Redoubt No. 9 at Yorktown, to Millard Fillmore. Munson did not see the rebellion, which tested the Constitution that owed its existence to him and other Revolutionary War soldiers.

Note: Munson’s name was later spelled Monson. It has been changed in some quotes here for consistency.

References: Pennsylvania Gazette and Weekly Advertiser, Philadelphia, Pa., Feb. 4, 1781; Munson, The Munson Record; Thatcher, A Military Journal during the American Revolutionary War; Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution; Howe, Historical Collections of Virginia; Lossing, Hours with Living Men and Women of the Revolution; Eneas Munson pension file, National Archives.

Joe Bauman is a retired journalist living in Salt Lake City who worked as a reporter at a television station in Salisbury, Md., two newspapers on the Eastern Shore, and for 36-1/2 years before his retirement in 2008, the Deseret News in Salt Lake City. He interviewed American veterans of every major conflict since the Spanish-American War. Fascinated with historical photography, he has collected thousands of original images from 1842 through 1920. His family owns the world’s largest collection of original photos of identified Revolutionary War veterans—only 14 because so few lived long enough to be photographed. His two books of veteran photographs are available as e-books at Amazon.com: Don’t Tread On Me, Photographs and Life Stories of American Revolutionaries, with eight daguerreotypes, and The last Men of the Revolution, a reprint of an 1864 book illustrated with five of his original cartes de visite. His fondest wish is to someday combine the books and find a print publisher.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.