By Dione Longley and Buck Zaidel

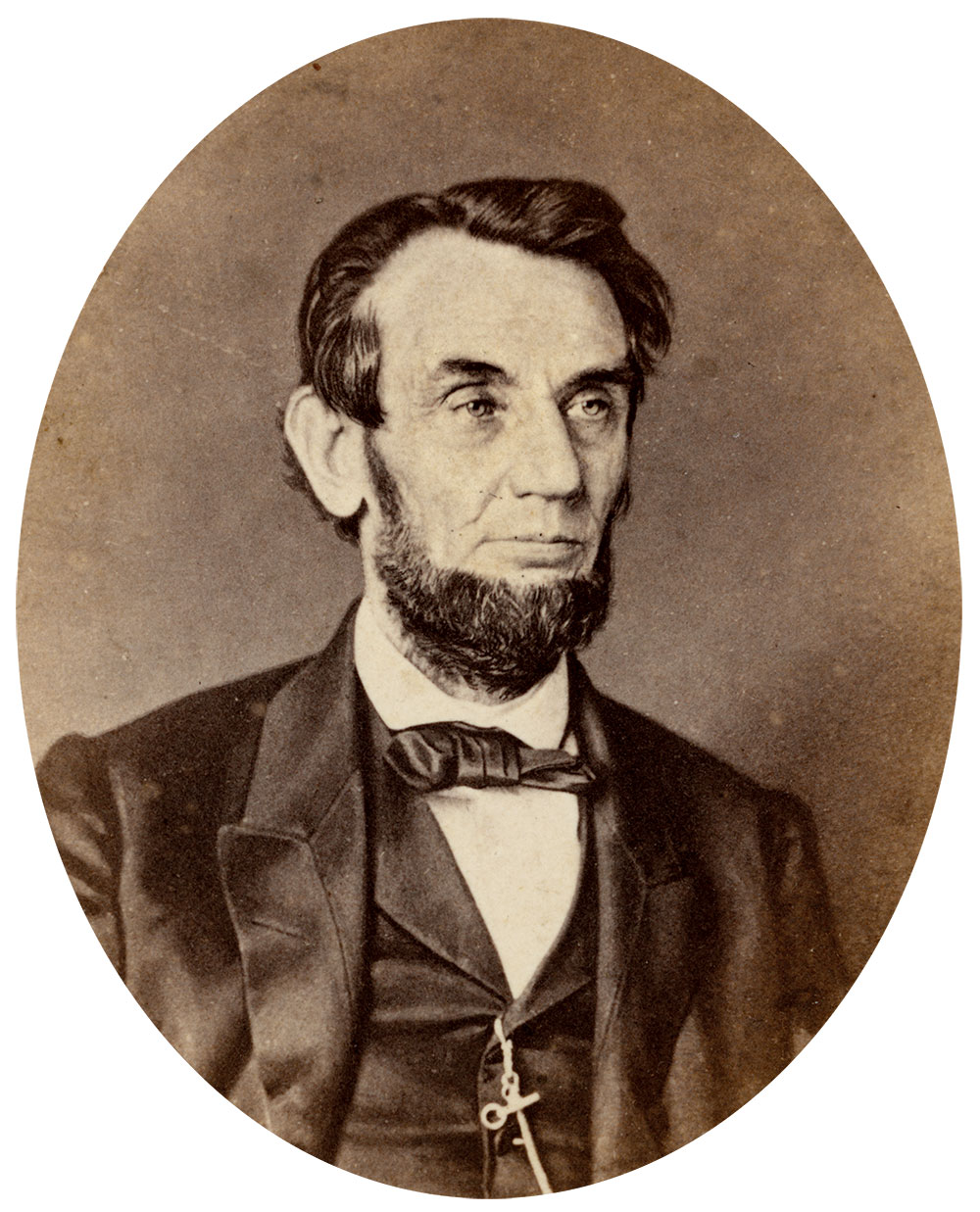

A crowd burst into enthusiastic and sustained applause when President Abraham Lincoln entered the grand hall of the Baltimore Sanitary Fair on the evening of April 18, 1864. Invited to deliver remarks at the inaugural exercises, Lincoln grasped the significance of the place and time.

Joining other dignitaries on a platform erected in front of a fountain and towering floral display, Lincoln’s tall, spare form could barely be seen above the cheering, handkerchief-waving throng. After the initial burst of enthusiasm subsided, he offered welcoming remarks.

“Calling to mind that we are in Baltimore,” he said, “we cannot fail to note that the world moves. Looking upon these many people assembled here to serve, as they best may, the soldiers of the Union, it occurs at once that three years ago the same soldiers could not so much as pass through Baltimore. The change from then till now is both great and gratifying. Blessings on the brave men who have wrought the change, and the fair women who strive to reward them for it!”

The crowd cheered Lincoln on. Everyone present remembered how Baltimore’s streets had resounded with shouting and gunfire when secessionist mobs violently attacked Union troops entering the city on April 19, 1861. And two months before the riot, the press had lampooned Lincoln’s secret passage through Baltimore under cover of darkness en route to his inauguration.

Since then, of course, the war had changed everything. Lincoln’s listeners knew well how three years of brutal fighting had altered the country. The President continued speaking, turning to another momentous change, “the process by which thousands are daily passing from under the yoke of bondage.”

Maryland was still a slave state. More than 87,000 enslaved people inhabited its borders according to the last federal census. Yet on that day in 1864, Baltimoreans had cheered 3,000 Black soldiers who marched in a parade celebrating the opening of the fair. The President’s speech nudged his Maryland audience to push forward the change to freedom. He was perhaps laying the groundwork for a move toward emancipation at the state’s upcoming Constitutional Convention. Lincoln’s cordial presence and carefully worded remarks might help bring him votes in the presidential election that was six months away.

Right beneath the noses of the thousands of fair-goers, another dramatic change was taking place: American women were transforming their roles in society. It had begun a few days after the war started, when a group of New York women gathered to brainstorm how they could help the Union troops. The group envisioned a more substantial mission than just knitting socks for the soldiers. Out of this early meeting grew the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC), a government-sanctioned organization operated by civilians. Its aim was to help the soldiers in ways the government could not, by improving conditions in camps and hospitals, delivering needed supplies, and caring for the sick and wounded.

The Sanitary Commission movement grew from predominantly white, upper-class ladies to “tens of thousands of women across the economic spectrum, from both urban and rural areas of the north and west.”

Those in leadership positions at the USSC were predominantly white, upper-class ladies. But the movement had rapidly grown to encompass tens of thousands of women across the economic spectrum, from both urban and rural areas of the north and west.

In short order, the Sanitary Commission established a complex network that rapidly responded to soldiers’ needs. In nearly every community across the North, women formed soldiers’ aid societies, meeting to make bandages, mittens, quilts, pickles, jam—whatever might help the soldiers. The USSC persuaded these groups (by war’s end some 7,000 existed) to send the supplies they made to USSC warehouses where volunteers organized them so that they were instantly available to send to those who needed them most.

Sanitary Commission workers arrived at battlefields, sometimes before the fighting was over, bringing bandages, blankets and medicines, all critical for the thousands of wounded. Soldiers standing picket in snowstorms received wool mittens knit with an index finger so they could fire their guns. Hospital stewards opened boxes containing slippers and checkerboards for their patients. In addition, the USSC sent scores of women to become nurses in the military hospitals, caring for wounded from the Union and the Confederacy.

The Sanitary Commission continually needed to raise funds to support its mission. To this end, the USSC held a fair in Chicago in 1863, and it proved wildly successful. Now Maryland’s women threw themselves into staging an immense fair to raise money for the USSC and the U.S. Christian Commission, another major philanthropy supporting the troops.

Origins and splendor of the fair

The fair was the brainchild of two Baltimore women who held a meeting on Dec. 3, 1863, inviting “Union ladies” to attend. Their proposal met with immediate enthusiasm. By December 19, more than 75 women from around the state had joined the State Fair Association of the Women of Maryland. Three members paid a flying visit to Boston’s Sanitary Fair to observe, and then the women got to work.

This group of largely inexperienced women had four months to organize and conduct an event of enormous scope. Though they may have lacked confidence, they did not lack patriotism or selflessness.

Newspapers published their persuasive appeal across Maryland: “The help of women is needed in this dark hour of our Country’s calamity.” The organizers knew that the fair would require long hours of difficult labor from hundreds of volunteers; the responsibilities would be overwhelming—especially for those who were already struggling with the demands of family, and for those whose husbands were soldiers. And times were hard. “Let us heroically resolve to make sacrifices, to rouse ourselves to meet the demands upon us,” the Association entreated its female readers.

At the Association’s suggestion, women formed groups in their own towns or counties, where they solicited donations of money, supplies or salable goods. Members also made items such as embroidered handkerchiefs, small watercolor paintings or lace mitts that would sell at their group’s table.

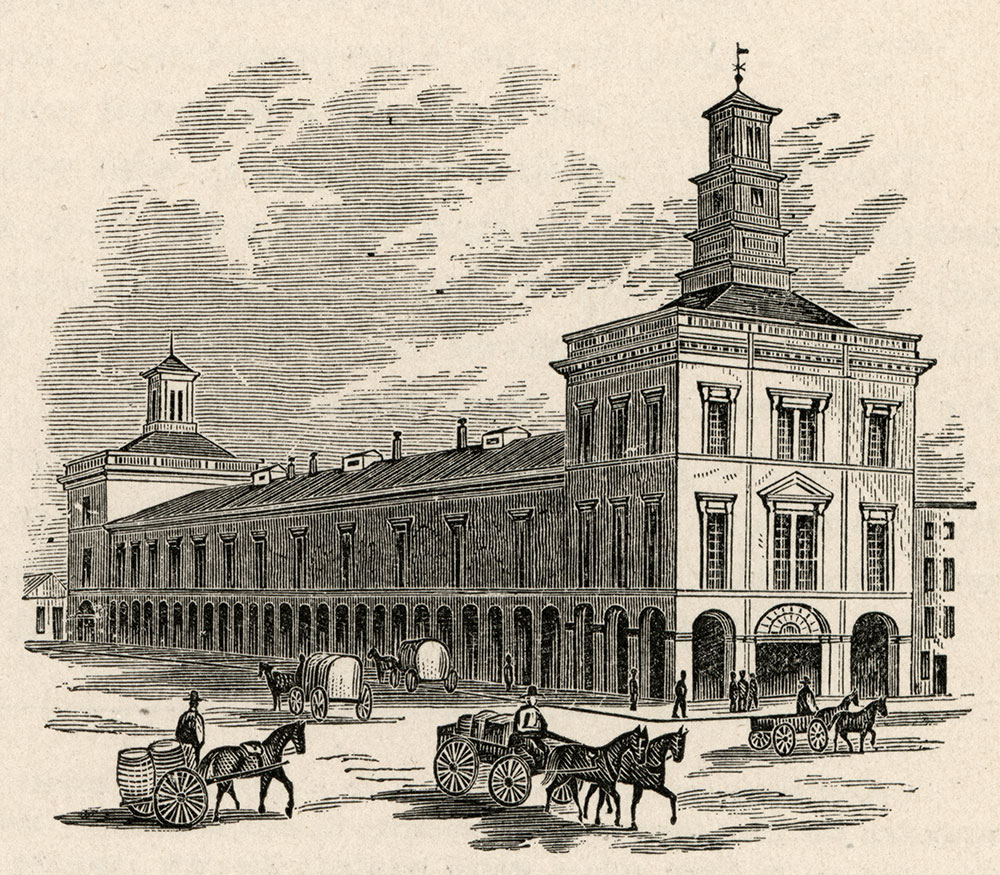

The Maryland Institute, a college located in a sprawling two-story brick building covering an entire block and topped by a pair of clock towers, served as home for the 12-day event. Informally known as the Baltimore Sanitary Fair, its official name was the Maryland State Fair for U.S. Soldier Relief.

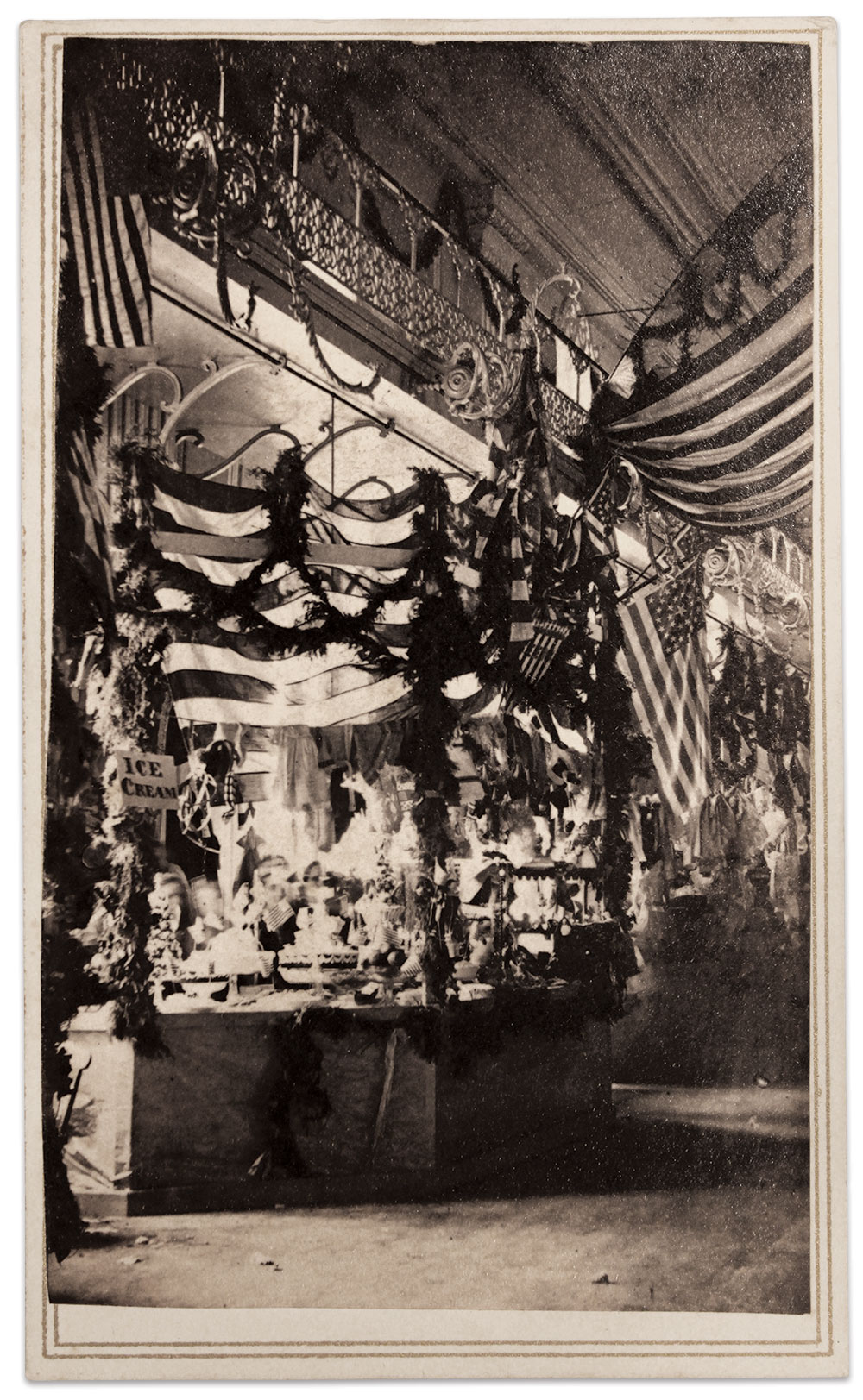

“On entering the main hall a magnificent spectacle catches the eye of the visitor. The immense saloon is one grand flood of light, furnished by about one thousand jets of gas,” reported the Baltimore Sun. Everywhere around the huge hall hung American flags, their colors bright in the light of the gas jets. Flowers and evergreen garlands adorned the stands and tables lining the walls, and an arch draped with American flags rose across the room, topped with the word “UNION” in huge letters, all lit by more gas jets.

The impressive floral arrangement used as a backdrop for the fair’s inaugural was but one of the displays. The fragrance of the fresh-cut flowers from Mary Lincoln’s White House garden along with the scent of boughs and boughs of evergreens competed with the aroma of baked beans coming from the New England Kitchen, a recreation of a colonial scene complete with volunteers cooking over fireplaces, and women operating antique spinning wheels. More volunteers served up refreshing soda water and lemonade at Jacob’s Well.

Brightly decorated tables stretched down the long eastern and western walls of the great hall, ladened with everything from cakes to canes for sale. One attendee called out a few of the eye-catching displays: “Here was a goddess of liberty, draped in the folds of Old Glory; a flannel skirt worked in red, white and blue by a Union lady of Charleston; a bridal party of dolls on their way home from church; a chess table worked in beads; the battle-flags of the Second and Third Maryland; aprons made by soldiers; leaves and flowers of wax; and iron-holders with appropriate mottoes.” The same attendee also pointed out the book and photograph table, an array of gifts from other cities and countries, and a mirror-lined “fishing pond” where participants cast their lines to hook small gifts.

The fair even had its own daily newspaper, the New Era, sold to attendees by an army of boys and girls as well as five soldiers. The title of the publication captured the spirit of the fair’s theme, the old Baltimore of 1861 compared to current times. And in the gallery hung a large silk American flag with an embroidered motto: “April 19, 1864—May the Union and Friendship of the Future obliterate the anguish of the Past.”

As the organizers anticipated, staffing and maintaining the tables required a significant effort. One volunteer, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Randall, 36, had left her Annapolis home and her numerous children (she was already expecting another) to manage two tables. Writing to her husband, Elizabeth explained, “‘my attendance’ at the fair has necessarily been from breakfast time till ten o’clock at night, without intermission” as she directed all the necessary tasks.

Photographing the fair

The visual record of the fair is minimal, which seems unusual considering the hoopla and a visit by the president. In his comprehensive 2012 book Maryland Civil War Photographs, author Ross J. Kelbaugh stated, “Only one photograph believed to be the Sanitary Fair has been located, and it is of limited value.” The image to which Kelbaugh refers is the view by the Fischer Brothers, who operated a gallery in the city. An engraving of the main hall (left), appeared in the May 14, 1864, issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.

No photographs by prominent Baltimore photographers Daniel and David Bendann have yet surfaced. This perhaps comes as no surprise as the brothers were believed to be sympathetic to the Southern cause and, if true, would likely have avoided a fundraiser for Union troops.

One photographer left behind a visual record that has only recently come to light. This cache of cartes de visite, published here for the first time, adds a wealth of previously unknown detail. The photographer captured the fair’s overwhelming spirit of patriotism in several interior shots of the Maryland Institute. He also created, with an artistic eye, smaller vignettes focusing on specific features.

The photographer, 19-year-old Baltimorean Augustus Ducas Clemens, Jr., began his career as early as 1859, when his family returned to Baltimore after a 2-year stint as booksellers in Leavenworth, Kan. Considering his age and inexperience, Clemens likely apprenticed with daguerreotypist John H. Young. When Clemens joined Young’s gallery is not clear, but his separation date is. In May 1868, he opened his own gallery on 73 West Baltimore Street—the same address listed on the imprint on the mounts of these cartes. Evidence suggests Clemens printed these images from negatives made in 1864 after he opened his own business.

The photographer, 19-year-old Baltimorean Augustus Ducas Clemens, Jr., began his career as early as 1859, when his family returned to Baltimore after a 2-year stint as booksellers in Leavenworth, Kan. Considering his age and inexperience, Clemens likely apprenticed with daguerreotypist John H. Young. When Clemens joined Young’s gallery is not clear, but his separation date is. In May 1868, he opened his own gallery on 73 West Baltimore Street—the same address listed on the imprint on the mounts of these cartes. Evidence suggests Clemens printed these images from negatives made in 1864 after he opened his own business.

Epilogue

The fair drew thousands of visitors from Maryland and beyond, and netted about $80,000 after expenses (about $1.5 million in today’s dollars). Half the proceeds went to the USSC, and the rest to the U.S. Christian Commission.

Efforts by the women of the Sanitary Commission changed the lives of hundreds of thousands of Union soldiers for the better, and helped soften the horrors of war. Their contributions also furthered the cause of equal rights for women in the United States. Their actions and deeds illustrate Clara Barton’s postwar observation that as a result of the war “woman was at least fifty years in advance of the normal position which continued peace would have assigned her.”

President Lincoln’s visit apparently bore fruit as well. When, on Sept. 6, 1864, the Constitutional Convention completed its work, it included a dramatic declaration: “Immediate emancipation of all slaves in Maryland.” And two months later, Lincoln defeated George B. McClellan, securing his second term in the White House. Lincoln did so with the help of Marylanders, who gave him the state’s popular vote.

Clemens’ career as a photographer ended about 1870. He followed his father into the real estate business and built a fortune as a suburban residential developer during the latter half of the century. By one estimate, his work contributed to the construction of about 2,000 homes in the Baltimore area. He died in 1909 at age 64, survived by is wife, Mary, two sons and a daughter.

Clemens’ 10 years in the photography business was little if at all remembered. These images of the Baltimore Sanitary Fair are part of his legacy as a photographer. One wonders if there are more views of the fair waiting to be found.

References: The Sun, Baltimore, Md., April 19, 1864, May 16, 1868, and Nov. 11, 1909; The Burlington Free Press, Burlington, Vt., Sept 13, 1865; The Cecil Whig, Elkton, Md., Jan. 9, 1864; Der Baltimore Wecker, April 19, 1864; “Maryland College of Art History,” maryland-institute-college-of-art-mica/history; Elizabeth Randall to Alexander Randall, May 1, 1864, Philpot-Randall Family Papers, Maryland Historical Society; Genealogy and Biography of Leading Families of the City of Baltimore and Baltimore County, Maryland; Goodrich, The Tribute Book: A Record of the Munificence, Self-Sacrifice and Patriotism of the American People during the War for the Union; Barton, “Memorial Day Address,” May 30, 1888, Clara Barton Collection, Smith College Archives, Northampton, Mass.; email exchange with photographic historian Dr. Jeremy Rowe, Feb. 1-2, 2023.

Dione Longley and Buck Zaidel co-authored Heroes for All Time: Connecticut Civil War Soldiers Tell Their Stories, a book featuring the images, artifacts and exploits of the citizen soldiers who made up the regiments from Connecticut who volunteered to save the Union and fought to set men free during the Civil War.

The Baltimore Sanitary Fair Images of A.D. Clemens, Jr.

Cartes de visite from the Buck Zaidel Collection.

Mineral water from Jacob’s Well

Mineral water from Jacob’s Well

An exhausted volunteer leaned on Jacob’s Well, which supplied cold mineral water for guests. In the adjacent broader view, below, the sign for Jacob’s Well is visible under crossed flags on the upper level. A keen eye will also note, under the flag staffs, a large framed portrait of a soldier. Was he a Maryland native?

The wedding party

The wedding party

A trio of porcelain dolls formed an elegant wedding party, which probably graced the children’s table. One wonders if Clemens’ seven-year-old sister, Emily, had anything to do with her brother’s choice of subject.

Ready for the crowds

Clemens captured this view without visitors; he probably took his photographs before the fair opened. Once the doors opened, crowds were so dense that it could be difficult to move through the throng, especially with the immense hoop skirts many women wore. Oddly, the right edge of this image (as well as Clemens’ other two long shots) is superimposed from a similar view. You can see the same strip running just to the right of the left margin. A figure standing in the doorway on the balcony appears at both left and right sides of the image. One theory to explain this duplication holds that Clemens used a multiple-lens camera designed for cartes de visite, and rotated the camera on its side to create a horizontal view. The subsequent print was awkwardly cropped.

Classic tableau

Classic tableau

The Ladies German Relief Association presented a tableau of a nursery rhyme, “There was an old woman who lived in a shoe,” with dolls representing the rhyme’s “so many children.” When President Lincoln visited the booth on opening night, a costumed member—perhaps the young model pictured here—presented him with a bouquet of flowers and “was kissed by him in return.”

Works of art

Works of art

For an extra 50 cents, visitors strolled through the upstairs art gallery, which boasted statuary donated by a local marble works, and 120 paintings, many borrowed from collectors. Art aficionados marveled at landscapes by artists such as Asher Brown Durand and Sanford Robinson Gifford, as well as portraits and still-life works. “There are but a few indifferent pictures in the entire collection,” proclaimed The Sun.

Painter’s ice cream

People passed through a sea of flags to reach tables offering everything from cakes to ladies’ bonnets. In the background a sign advertised “Painter’s Ice Cream,” a family business in Owings Mills, Md. The company suffered a sudden loss of inventory in July 1864 as their ice cream wagon crossed paths with some hot, dusty Confederate cavalry operating as part of Jubal Early’s foray into Maryland.

Miniature skaters diorama

This mirror-lined diorama must have provided quite the optical sensation for young and old viewers alike. In winter attire, are the figures skaters on a pond? Did the base rotate, adding to an ever-changing imagery in the mirrored faces?

Nod to the Naval Academy?

Nod to the Naval Academy?

The floral anchor may have been a salute to the area’s naval connection. Maryland’s capital city, Annapolis, located about 32 miles southeast of Baltimore on the Chesapeake Bay, had been home to the Naval Academy since 1845. Officials temporarily relocated the Academy to Newport, R.I., in 1861 through the war’s end due to safety concerns rising from secession sentiment in the region and close proximity to Confederate territory.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.