By Mike Fitzpatrick

Late in his life in the spring of 1929, Union veteran and retired school principal John Davis Billings received a letter from Lucy Bowen, a young woman on the yearbook staff of the State Normal School in Bridgewater, Mass. Billings, an alumnus, had graduated in 1866 and went on to a six-decade career as an educator and schoolmaster at an elementary school.

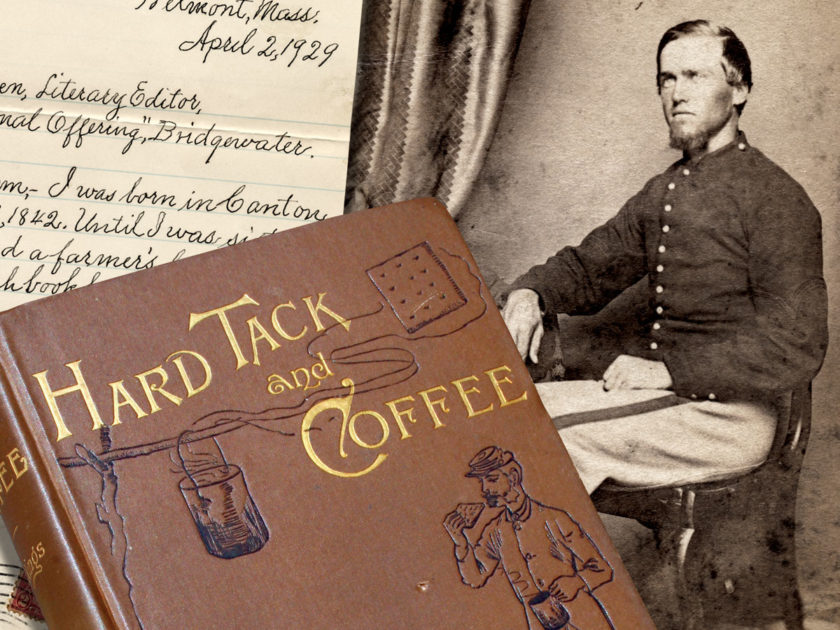

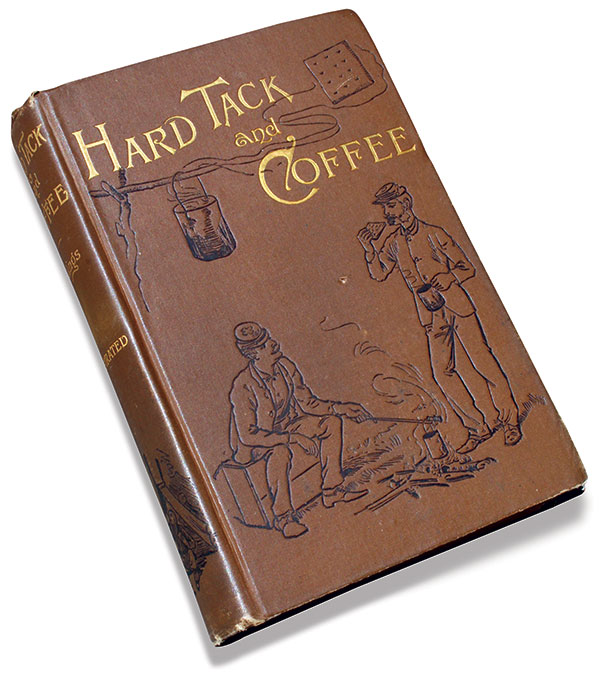

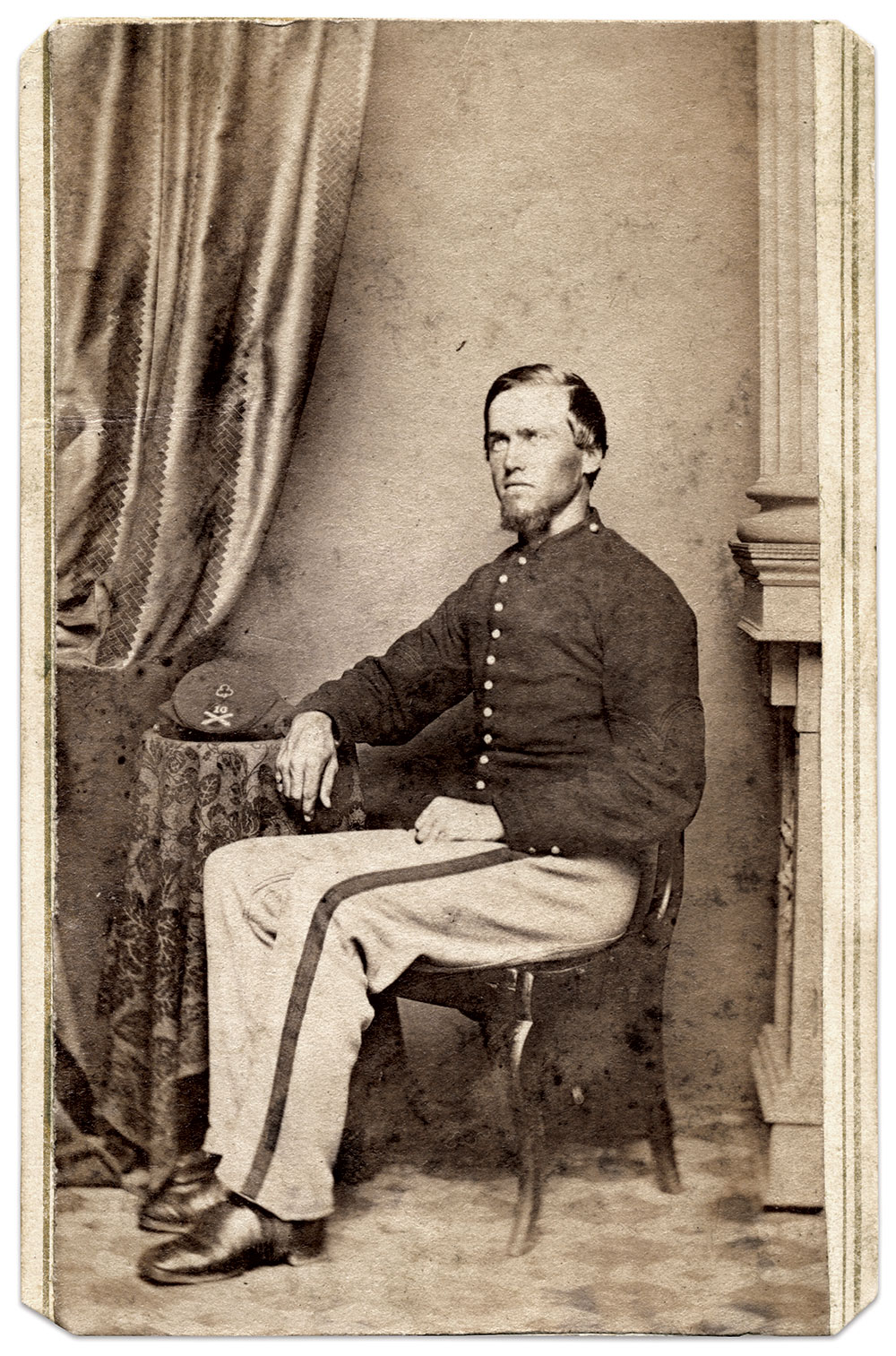

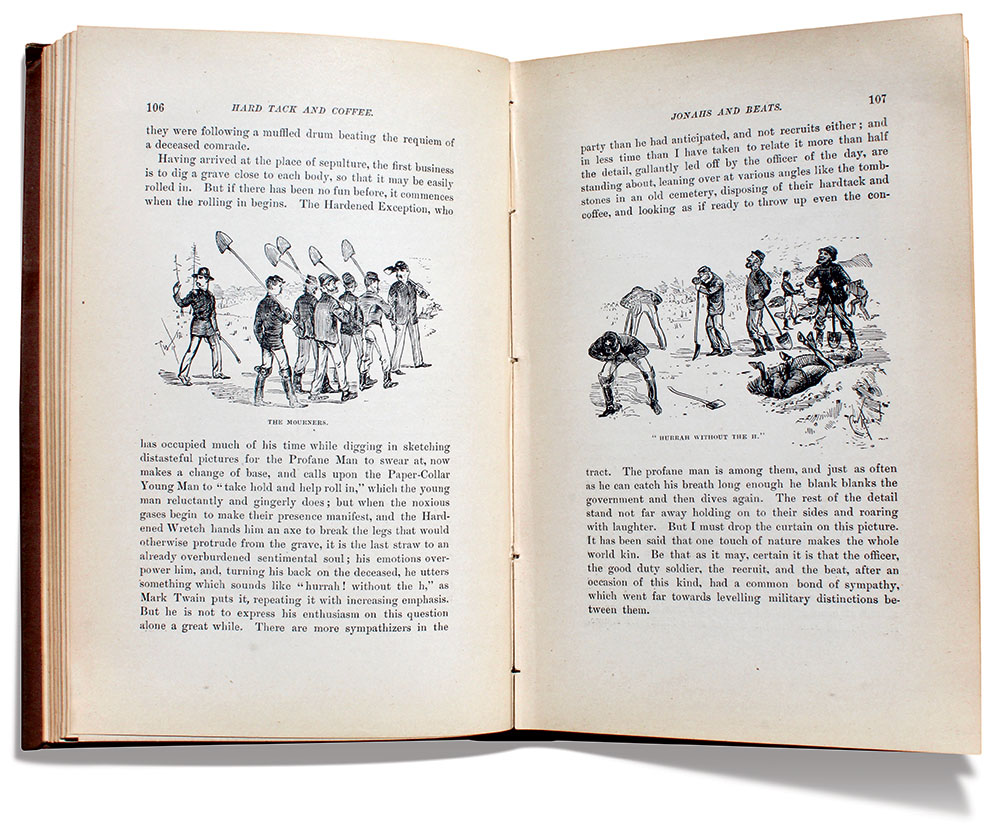

During the Civil War, Billings had spent three years with the 10th Battery, Massachusetts Light Artillery. Years later, he wrote the history of the Battery, which was published in 1909. But Billings is best remembered as the author of Hard Tack and Coffee. Subtitled The Unwritten Story of Army Life, the book’s almost conversational tone makes it unique among the thousands of war memoirs. It presents an honest and often humorous portrayal of the daily life of the common Union soldier. Organized in a comprehensive, encyclopedic approach, it discusses in detail nearly every aspect of a soldier’s life from enlistment, food, shelter, discipline and hospitals to army mules.

This literary treasure is often viewed as a Bible for Civil War re-enactors, and required reading for anyone seeking to understand the everyday life of the common soldier in the Union army. Originally published in 1887, the book has been continuously reprinted ever since.

Billings began his war service at age 19 in the summer of 1862. A tall youth, standing just a shade over six feet in height, with fair skin, blue eyes and brown hair, he enlisted in the 10th Battery at Boston. Over the next three years, he and his comrades served with the Union Army’s 3rd and 2nd Corps, and participated in numerous hard-fought engagements, including the battles of The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, North Anna River, Cold Harbor and the Siege of Petersburg.

Billings’ closest brush with disaster occurred at Reams Station on Aug. 25, 1864. His description in his History of the Tenth Massachusetts Battery Light Artillery in the War of the Rebellion paints a vivid picture of the chaos on that battlefield: “The Rebel infantry again advance to the assault. They are formed in three solid columns, and come as before, at the double-quick, with fixed bayonets, uttering their war-cry louder than ever. Nearer and yet nearer they come. But what can we do? As we had been unable from lack of ammunition to measure metal with their artillery, so now we have but one round of canister to administer as they cross the field, and keep another—our last—for closer quarters. Our troops have evidently given way, for the enemy have reached the works at a point opposite the church, and swarm over them. It is all over with us now, for, turning down the line, they advance towards us in three columns, one outside, one inside the breastwork, and one along its crest.”

As the Confederates closed in, Billings and his fellow artillerymen faced a stark choice: Surrender and take their chances in a prisoner of war camp or flee.

Billings recalled, “Before leaving the field I made my way up to the right of the line north of the church. Here I saw Gen. Hancock (Heaven preserve him for his distinguished bravery), followed by two or three of his personal staff, riding up to the main breastwork, waving his cap and shouting, ‘Come on! we can beat them yet. Don’t leave me for God’s sake!’ But not a half-dozen men responded to his appeal.”

Billings joined the overwhelming majority who abandoned the field. He met up with a group of a dozen of his comrades at one of the Battery’s caissons parked in the rear. “I was greeted with the utmost warmth as if restored from the dead, and such a greeting did every one receive on his arrival. That was a meeting I shall never forget; for if the writer ever rejoiced to see comrades in arms, it was the small band he met in the dusk of that historic August 25, 1864.”

The 10th suffered 28 killed, wounded and captured, 54 horses dead, and the loss of all its guns that day. The wounded included the Battery’s captain, Jacob H. Sleeper. The Massachusetts Adjutant General’s Report noted, “Its position was a very unfortunate one, and its heavy loss was no reflection on the courage of the officers and men.”

Billings and the survivors continued on through the Appomattox Campaign and the surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia. Billings mustered out on June 9, 1865, with the exalted rank of corporal.

In 1870, Billings married Mary Phillipa Cotton Whitney. She bore him two children before her death in 1906. A year later, the then 64-year-old Billings married Katherine Wight, a woman about 27 years his junior. They had three children together and adopted a fourth.

Billings and his wife were well into raising their family when Lucy Bowen’s letter arrived in 1929. Born in 1908, Lucy excelled in sports, participated in the French and Library clubs, and served as Literary Editor on the yearbook staff. The quote she chose for her 1929 yearbook sketch, “By the work one knows the workman,” is attributed to French poet Jean de La Fontaine (1621-1695).

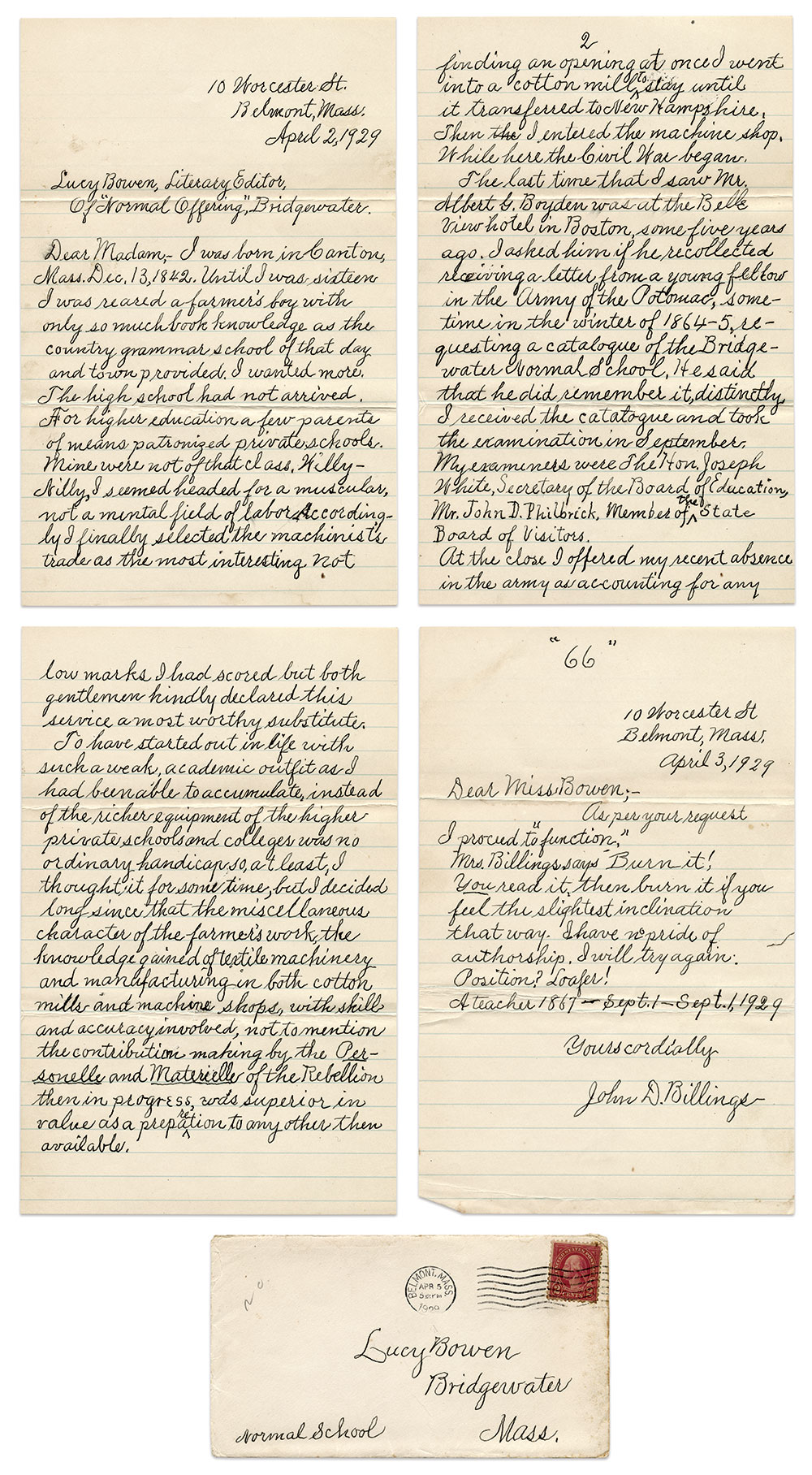

Though Bowen’s letter to Billings is lost, a review of the 1929 yearbook reveals that she reached out to several former educators about their teaching origins. Billings, now 86 and in feeble health but mentally alert, shared his story.

“Until I was sixteen I was reared a farmer’s boy with only so much book knowledge as the country grammar school of that day and town provided. I wanted more. The high school had not arrived. For higher education a few parents of means patronized private schools. Mine were not of that class. Willy-Nilly, I seemed headed for a muscular, not a mental field of labor. Accordingly I finally selected the machinist’s trade as the most interesting. Not finding an opening at once I went into a cotton mill to stay until it transferred to New Hampshire. Then I entered the machine shop. While here the Civil War began.”

Billings also mentioned Albert Gardner Boyden (1827-1915), who had served as principal for almost a half century, from 1860 until his retirement in 1906. Boyden played a small but important role as Billings contemplated his postwar plans during the war’s final months.

“The last time that I saw Mr. Albert G. Boyden was at the Belle View hotel in Boston, some five years ago. I asked him if he recollected receiving a letter from a young fellow in the Army of the Potomac, sometime in the winter of 1864-5, requesting a catalogue of the Bridgewater Normal School. He said that he did remember it, distinctly. I received the catalogue and took the examination in September. My examiners were The Hon. Joseph White, Secretary of the Board of Education, Mr. John D. Philbrick, Member of the State Board of Visitors. At the close I offered my recent absence in the army as accounting for any low marks I had scored but both gentlemen kindly declared this service a most worthy substitute.”

Billings concluded with a recognition of the value of his army education: “To have started out in life with such a weak academic outfit as I had been able to accumulate, instead of the richer equipment of the higher private schools and colleges was no ordinary handicap so, at least, I thought it for some time, but I decided long since that the miscellaneous character of the farmer’s work, the knowledge gained of textile machinery and manufacturing in both cotton mills and machine shops, with skill and accuracy involved, not to mention the contribution making by the Personelle and Materielle of the Rebellion then in progress, was superior in value as a preparation to any other then available.”

At the end of the letter, Billings added a postscript that hints at his humor and humility:

Dear Miss Bowen; –

As per your request I proceed to “function.”

Mrs. Billings says Burn it!

You read it, then burn it if you feel the slightest inclination that way. I have no pride of authorship. I will try again.

Position? Loafer!

A teacher 1867 – Sept. 1 – Sept. 1, 1929

Billings died four years later at age 90.

Lucy Bowen graduated with the Normal School’s Class of 1929. She married Robert W. Sealey and they began a family in Southboro, Mass., that grew to include three daughters. Lucy passed in 1969 at about age 61. Her husband died two years later.

Mike Fitzpatrick has been an avid photo collector for more than 30 years. He has authored several magazine articles and written a Civil War novel, The Letters From Fiddler’s Green. He is currently writing a history of Annapolis, Md., during the Civil War. He is an MI Contributing Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.