By Kurt Luther

In previous columns, we have typically focused on identifying a single photo of a soldier or a small group. What approach can we take when researching an album or grouping of numerous unidentified photos? Oftentimes, these photos have connections to each other, including overlapping provenance or subjects in common, that can support more effective sleuthing. However, researching a grouping benefits from a slightly different set of tools and techniques compared to individual photos. In this column, I will describe a recent experience sleuthing a grouping of Civil War photos that benefited from careful attention to the links between photographers and subjects found throughout its pages.

The focus of this investigation is a grouping of 76 cartes de visite of Civil War soldiers held in the archives of the American Civil War Museum (ACWM) in Richmond. The grouping, known as “Notebook #13,” comprises cartes of (white) Union officers associated with the Corps d’Afrique. The Corps d’Afrique, formed in June 1863 from a core of Louisiana Native Guard units, grew to about 30 Union regiments of Black infantrymen, cavalrymen and artillerists recruited from around Louisiana. In April 1864, it was absorbed into the larger U.S. Colored Troops organization, and its regiments re-designated accordingly. For example, the 1st Infantry Regiment, Corps d’Afrique (abbreviated “CDA” by contemporaries) became the 73rd U.S. Colored Infantry (USCI); the 1st Cavalry Regiment, CDA became the 4th U.S. Colored Cavalry; and so forth.

The Notebook #13 grouping caught my eye because it was fully digitized online and contained many intriguing images. My first step was to skim the collection and get a rough idea of its overall composition. About two-thirds of the photos were identified, with the remainder unknown. The identifications provided by the museum staff ranged from period ink inscriptions with valedictions (“Your friend, L. J. Hissong”) to partial IDs (i.e., “Manning,” “Captain Bailey”) and educated guesses. Almost all of the soldiers were junior or field-grade officers in uniform. Roughly two-thirds included photographer’s backmarks, providing valuable hints about their subjects and origins, and the officers’ poses varied widely from standing views to vignettes.

As I clicked through the museum’s website, I noticed a frustrating quirk. The 76 cartes were spread across four pages, but, as I navigated to the next page, the selection of images was random. Thus, “page 2” showed one subset of 20 images, and the next time I checked, it showed a completely different subset. This software bug made it nearly impossible to keep track of which photos I had already seen. Therefore, I decided to create my own database on my computer to give myself complete control over the investigation.

I fired up a free software program called Tropy, developed by the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. Tropy is designed for historians and other researchers who take dozens or hundreds of digital photos of primary source materials when they visit an archive, and then struggle to organize them when they get home. However, I find it works equally well for organizing large groupings of digitized Civil War photos for research purposes.

First, I created a new Tropy project. Then, I downloaded the image file for each photo’s front (and back, when available) from the American Civil War Museum website and imported it into Tropy, one at a time. The true power of Tropy lies in its tagging feature, which gives photo sleuths the flexibility to describe photos however they want using tags, and then search and group photos using those tags later on. I tagged each officer’s portrait with the key information in the item description: soldier name, military unit name, and photographer name; if the information was missing, I tagged it “unknown.” I used the prefixes S_, U_, and P_, for subject (i.e., soldier name), unit, and photographer, respectively, to group similar tag types together.

The import and tagging process was laborious. But by carefully and systematically examining each of the 76 photos and their descriptions, I gained a deeper, more thorough understanding of the collection than I might otherwise. As I processed each photo, I noted when information was missing or seemed incorrect. I examined the soldier’s face and uniform and the photo’s background for clues and unusual details. And I subconsciously noticed patterns and gaps emerging from the stream of data.

I tried to verify each piece of information as I added it. Sometimes, the museum’s information was correct and only required confirmation or adding a missing detail. I verified a photo inscribed in pencil as “John McNeil” by performing a facial comparison to a Library of Congress glass negative of Brig. Gen. John McNeil in uniform. Two photos of Lewis P. Mudgett lacked an associated military unit, but I was able to identify him as a captain in the 80th USCI and major of the 86th USCI by searching his name in the American Civil War Research Database (HDS) and finding a reference photo there. Similarly, Louis Edwin Granger had no connected military unit, but his unique name inscribed on the carte’s front allowed me to confidently identify him as a lieutenant in the 80th USCI. George Brackett and John C. Chadwick were identified with the 7th and 9th Infantry Regiments, CDA, which I updated to the 79th and 81st USCIs, respectively.

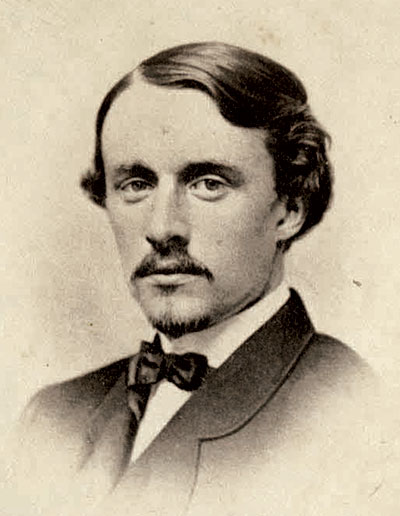

As I worked through these images, one immediately caught my attention. The museum staff had labeled the image “Col. James Shaw, Jr.” of the 7th USCI. I recognized the young, mustachioed man wearing a suit and bowtie. It was indeed a Col. Shaw, but not James Shaw. No, the man pictured here was Col. Robert Gould Shaw of the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry! I confirmed my intuition by locating two more identical views of Shaw in the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center’s MOLLUS-Mass collection. (By comparison, James Shaw, pictured in Roger Hunt’s Brevet Brigadier Generals in Blue, has an entirely different visage.)

Some photos had minor errors that I could easily correct during the processing stage. I suspected that many of these errors were caused by inaccurate transcription of period inscriptions coupled with a lack of confirmatory research. Most commonly, these errors affected soldiers’ names in minor ways. Capt. Clifford Eagle, 1st USCI, was given the middle initial L rather than F; to further complicate things, a modern sticker placed on the photo’s back identified the officer as the similar-sounding—but very different-looking—Surgeon William H. Egle, 116th USCI. George E. Getchell, captain and major in the 81st USCI, became the nonexistent “George C. Letchell.” Second Lieut. John W. Hamlin, 78th USCI was mistakenly labeled “L. Hamlin.” A headshot inscribed simply “Manning” on the front helpfully included a modern pencil inscription of the officer’s military service with the 81st USCI, allowing me to verify his identity as Capt. Elbridge G. Manning using a reference photo from HDS.

Other naming errors posed greater challenges, especially when they lacked information about a military unit to narrow down possibilities. In these cases, I found that reexamining the inscription proved surprisingly effective. After a good bit of staring, the erroneous name “George Potrim” became George C. Potwin, an officer in the 19th USCI. “S.M. Guilney” was, in fact, Col. Samuel Miller Quincy, a curly-haired Harvard alumnus who served in the 73rd, 96th, and 81st USCIs. The trickiest example of this lot, a bust view of a lieutenant with mutton chops, bore a period ink inscription transcribed as “A. G. Ausden.” No such name appeared in HDS or the National Park Service’s Soldiers & Sailors Database, and the Louisiana backmark gave little indication of the officer’s unit affiliation. Examining the inscription closely, I determined that the middle letters of the surname were least clear. I searched “A. G. A*den” on HDS, leveraging the wildcard (asterisk) character, and quickly found a promising result — Lieut. Abram G. Amsden of the 6th Michigan Infantry, a regiment that served alongside many USCTs in Louisiana.

A different class of errors placed officers in the wrong military units. A misreading of the period inscription on Charlie Bonsall’s carte incorrectly described him in the 52nd, rather than 62nd, USCI. There was no Samuel Johnson assigned to the 81st USCI, as the museum’s entry indicated, but a 1st Lt. Samuel E. Johnson did serve as adjutant of the 66th USCI.

Some photos, however, resisted my attempts at a quick verification or correction. In a few cases, they were completely unidentified, lacking any distinctive visual clues or even a photographer’s backmark to suggest a path forward. In others, I determined that the soldier’s name provided by the museum was clearly wrong, but the correct one was not obvious. These I marked as requiring further investigation and set aside for later.

When I finished tagging, I had a powerful research environment at my fingertips. All the tags were displayed on Tropy’s left sidebar, and I could easily click on any tag to see all the photos that shared it. I could also use the search bar to type in specific search terms. I began exploring the different tags, testing some of the theories I had developed during processing.

By glancing at the tag list, I could quickly see the distribution of photographers and military units represented in the collection. There were nearly 30 unique artists represented, mostly from Louisiana hubs like New Orleans and Port Hudson, but also a handful of exceptions, such as Boston and Washington, D.C. One such backmark on a carte of an unidentified, intense-looking officer in a sack coat read, “C. Duhem & Bro. / Photographers on the Rio Grande.” On a whim, I searched for this unusual phrase on Google. Unexpectedly, there was one hit. A 2019 doctoral thesis about New Mexico photography by Dr. Devorah Romanek featured another copy of the same view! Hers was augmented on the front with a period ink inscription of the soldier’s name — “D. H. Brotherton, USA” — and on the back, in period pencil inscription, the location of the Duhems’ studio—Albuquerque, New Mexico Territory—and even the date: June 5, 1867. David H. Brotherton, an 1854 graduate of West Point, served as a captain in the 5th U.S. Infantry during the Civil War, followed by decades of Regular Army service out West. A different wartime view of Brotherton in Romanek’s thesis confirmed the ID.

Photographers’ backmarks helped me solve another photo mystery in the collection. The Tropy tags revealed that one of the best-represented studios in the collection was Nichols & Bros., based in St. Louis, Mo., with six different photos. However, none of the six had a solid ID for the pictured officer. The most promising one, depicting a goateed field-grade officer, had a partial inscription inked on the back with the first name cut off; only the middle initial M and surname “Houston” were visible. I hoped that if I could identify that officer, it might also shed light on the other five.

I searched HDS for soldiers with the last name Houston, sorted by results with middle initial M, and then inspected each result for evidence of field-grade rank. Only one name fit the bill: Maj. George M. Houston. Better yet, he served in a Missouri unit, the 2nd Cavalry (Merrill’s Horse), that aligned with the St. Louis-based studio. Eagerly, I looked through the other reference photos of 2nd Missouri Cavalry officers available on HDS. Soon, I made a second ID, an identical view to one of the five other Nichols & Bros. photos in my set! The soldier, another field-grade officer, was Lieut. Col. Charles B. Hunt. For unknown reasons, the museum had identified the CDV as “George K. Anderson,” a name absent from any Civil War records database. I was unable to find any link between the men of the 2nd Missouri Cavalry and the Corps d’Afrique.

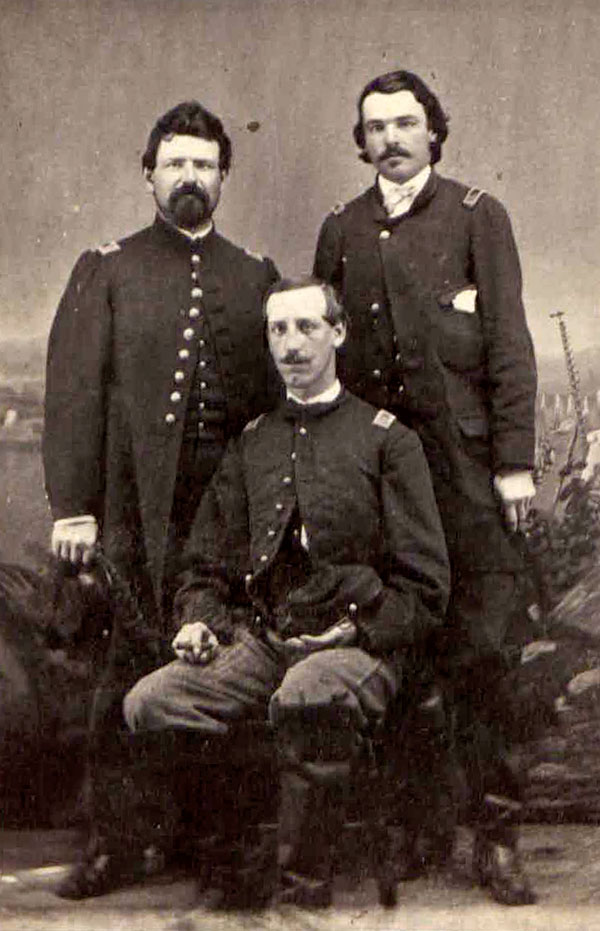

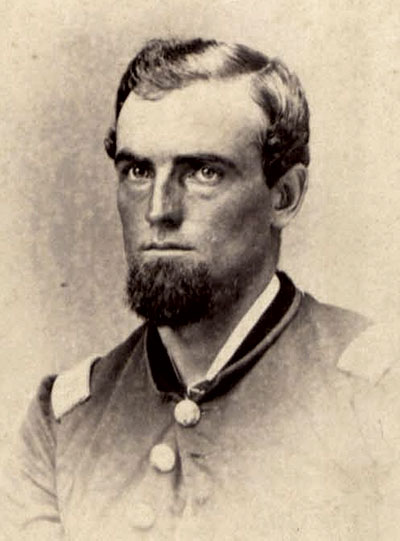

The tagging process also highlighted connections between four photos in the collection (all taken by the studio Brooks & Blauvelt) that revealed several new soldier identities. Two were duplicates showing a bust view of an unidentified junior officer with styled mustache tips and a dimpled chin. The same man appeared in two other cartes, both group portraits. In the third photo, he stands next to a seated officer. The period ink inscription on the back is transcribed incorrectly as “L. J. L. Bau,” identified as a captain in the 79th USCI. A closer look reveals the correct name to be C[harles] J. C. Ball. But which of the two men is Ball? The fourth photo showed the mustachioed man seated with two new officers standing behind him. This photo’s ink inscription is correctly transcribed as Capt. Edwin C. McFarland, also of the 79th USCI. Similarly, however, we don’t know which man is McFarland.

I searched the surnames Ball and McFarland in the MOLLUS-Mass digital collection, which includes several pages of 79th USCI officers. In a stroke of luck, I found identical copies of both group portraits among their holdings, and Capt. Ball was identified in both of them. Capt. Frederick H. Mann was identified as the seated man in the third photo, and another reference photo of McFarland in the MOLLUS-Mass collection confirms him as the officer standing to the right behind Ball. Thus, using the process of elimination, I was able to identify all but one of the seven officers depicted in the four photos. As a bonus, I was able to provide the names of two unidentified officers in the MOLLUS-Mass copies of the photos.

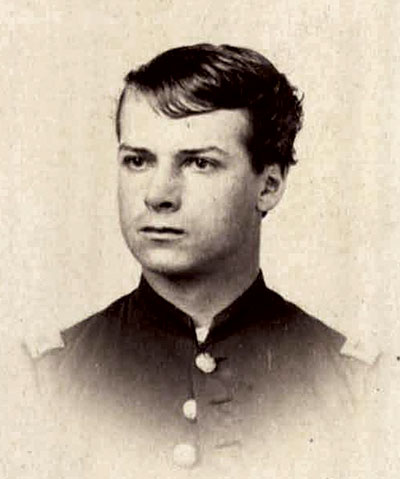

My examination of the MOLLUS-Mass reference photos yielded a couple more discoveries. Building on my success with the 79th USCI reference photos, I expanded my search to other Corps d’Afrique regiments. As I paged through the reference photos of 81st USCI officers, I recognized the familiar faces of Second Lieut. Charles M. Bucklin and Capt. Augustus J. Nickerson. These were identical copies of unidentified cartes in the Notebook #13 grouping, and I was delighted to be able to restore their names and stories.

While my initial effort to research the American Civil War Museum’s Notebook #13 collection was fruitful, the work is far from done. Twenty-seven cartes remain unidentified, many with promising leads, such as partial inscriptions, regimental numerals, and small-town studio backmarks. My favorite unsolved mystery is a young man wearing a bulky officer’s overcoat and a kepi with an infantry hunting horn bearing a single, illegible numeral. The same officer appears in a different view in the MOLLUS-Mass collection, wearing his sword, sash and a broad-brimmed hat. Although he is grouped with other 81st USCI officers, his photo is, oddly, unlabeled, leaving his identity a mystery. My sincere hope is that future research by me and other photo sleuths can solve this mystery and identify all 27 of the remaining unknown officers.

Note: The portraits illustrating this column are MOLLUS-Mass photographs in the collection of the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center. The author used these images as a reference to identify the subjects in the ACWM Collection.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is an MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.