By Ronald S. Coddington

The war came to Camden on a winter’s day in 1865. For weeks, The Camden Confederate and other South Carolina newspapers reported the steady advance of Sherman’s Army. The fall of the state capital in Columbia on February 17 ended any hope of escape for its citizenry.

Camden’s proximity to Columbia, a few dozen miles northeast, and its rail connection to the coastal hubs of Charleston and Wilmington, N.C., made it a strategic target.

On February 22, while embers from the smoking ruins of the capital still glowed, skirmishers clashed near the gentle banks of the Wateree River, not far from Camden. In the past, residents celebrated the birthday of George Washington. Less fondly remembered was a battle fought more than 80 years earlier that ended in bitter defeat for the Americans—and Lord Cornwallis’ redcoats garrisoning the town.

This time, the bluecoats had the upper hand. Sherman’s troops skirmished in and around Camden, and parts of the town were burned on February 24.

Less than 24 hours later, a contingent of Sherman’s troops conducted a reconnaissance through Camden. It included the veteran volunteers of the 12th Illinois Infantry. Formed as the First Scotch Regiment in 1861, its ranks had marched out of Chicago sporting jaunty bonnets with thistle, a tribute to the native land of its colonel, John McArthur. The Illinoisans had come a long way since then, slogging through the South and earning its reputation for hard fighting at Fort Donelson, Shiloh, and elsewhere.

Now, outside Camden during the war’s waning weeks, the 12th spent three days northeast of town on picket. This duty provided the men with something of a respite from the fast-paced marching and tearing up rail lines that had occupied their time since breaking camp in Savannah at the end of January.

Carolina connection

About 10 miles east of Camden lay the Turner farm. Patriarch John F. Turner had spent his entire 54 years living and working on the land, which supported his wife, Jane, and teen-aged son, Ben. A year before cannon fire at Fort Sumter ignited the war, Turner dutifully reported the five enslaved children in his possession on the appropriate federal census schedule.

By law, Turner need only provide their age and gender: Three girls, aged eight, 10, and 13, and two boys aged six and 12. Their names are currently lost in time with the exception of one: 12-year old Hannibal. He had been born on the farm Oct. 30, 1848, as recorded by Turner.

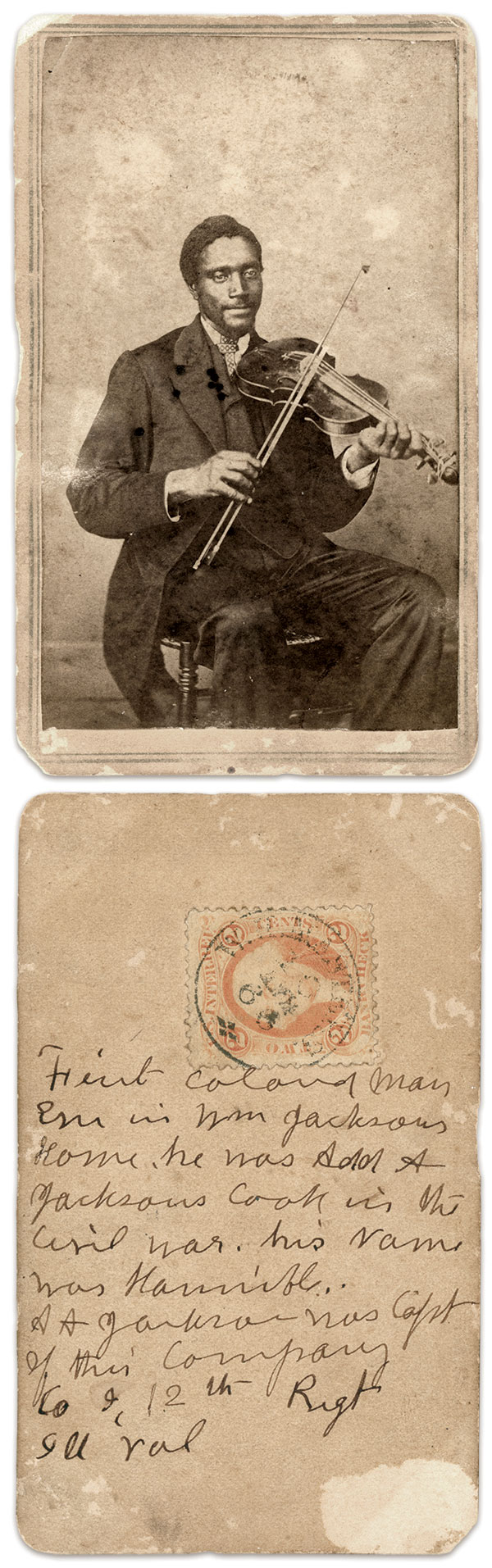

Hannibal’s exact whereabouts during the years between the census and the arrival of Sherman’s soldiers in the South Carolina heartland is not known. However, the inscription on the back of this portrait of him with fiddle in hand connects him to the 12th Illinois Infantry.

Hannibal may have met the men in the regiment in February when the Illinoisans picketed in the Camden area. One can easily imagine that Hannibal left the Turner place and became one of the hundreds of thousands of displaced persons across the Southern states to seek freedom and liberty with Father Abraham’s army.

Another scenario is possible. Hannibal may have left the Turner place before or after the arrival of Sherman’s soldiers, and traveled to the North, perhaps traveling by night to avoid detection by Confederate home guardsmen in the same way as escaped Union prisoners of war. He could have followed rail lines to the coast and hitched a ride on a vessel or taken his chances on foot through the Carolinas and Virginia.

Whatever his path to freedom, Hannibal became attached to the 12th and connected with the officer named in the photo inscription: Addison A. Jackson. The middle child in a family of five, his parents, William and Amelia, relocated the family from western New York to Illinois in the late 1840s, settling into the farming life outside Springfield.

By the time the war came, Jackson had left home and found work as a carpenter in Princeton, 115 miles west of Chicago.

In April 1861, when McArthur recruited Scots (and non-Scots) to join his new regiment and don the bonnet and thistle, Jackson did not respond. Three months later, after its three-month term expired and the 12th reenlisted for three years, Jackson joined Company I as sergeant. He proved worthy of his chevrons, rising to the rank of orderly sergeant shortly before the fighting at Shiloh, during which he suffered a wound. He recovered and participated in the major campaigns and battles through Tennessee and Georgia. In October 1864, he received his first lieutenant’s shoulder straps and led Company I on the March to the Sea and into the Carolinas.

The nature of the relationship between Jackson and Hannibal is unclear. The most likely explanation may lie in that Hannibal took on the role of personal attendant to Jackson, a common practice among U.S. officers. In some cases, the connection between officer and freedman became a stepping stone to military service.

And so it was here.

Two times a soldier

The men and officers of the 12th marched northeast into North Carolina, fording creeks and rivers and passing through communities small and large. On March 24, exactly a month after the Camden skirmish, the regiment entered Goldsboro and went into camp for two weeks to rest.

During this period, Hannibal became a soldier. On April 1, 1865, he enlisted in the 12th as an under cook in Company G. Congress and the War Department had created the position in 1863 as part of a series of legislative moves to better feed soldiers. One result was the appointment of a cook from the ranks of each company in white regiments. Cooks in companies with more than 30 men were entitled to two under cooks of African descent, who received pay and benefits.

Hannibal served in this capacity until the war’s end, from Goldsboro and Raleigh into Virginia. In early May at Alexandria, a mustering officer officially enrolled him. Later that month in Washington, D.C., the 12th marched in the Grand Review with the rest of Sherman’s “Bummers.” Parade watchers were thrilled by the contrast between the casual western soldiers to the formal Eastern boys in the Army of the Potomac.

The 12th did not dwell in the nation’s capital. It soon departed for Louisville, Ky. On July 10, 1865, the men mustered out of the army. A week later, they received discharges and final pay in Springfield, Ill., where President Lincoln’s remains had recently been laid to rest.

The inscription on Hannibal’s portrait reveals what happened next. He accompanied Addison Jackson to his family’s farm in Berlin, a short trip from Springfield. Hannibal became, as the writing notes, the first Black man to step into William Jackson’s home. Though the details of Hannibal’s visit went unrecorded, the event speaks to the spirit of the age in the wake of the end of slavery and dawn of a new era in race relations.

Peace would not come easy. Reconstructing the former Confederate states required soldiers to re-establish and maintain law and order. The U.S. Colored Troops, many with less than two years of service, played an outsized role garrisoning towns as many white regiments, their ranks depleted after three and four years of campaigning, mustered out and melted back into society.

One of these Black infantry regiments, the 110th, had formed in Alabama in late 1863 and mustered into the army in the summer of 1864. Its recruits included Ransom Frazier, who had enlisted in Company H. During his enslavement, Frazier had been trained as a blacksmith—a much needed vocation in the army. One regiment that happened to be in Alabama during this time, the 9th Illinois Mounted Infantry, got wind of his abilities. Orders were drawn up, and before Frazier knew it he had been detached for duty with the 9th.

The arrangement ended unexpectedly when Frazier deserted. One day in April or May 1864, he slipped away. At first, Frazier’s disappearance went unnoticed, perhaps because he deserted while on detached duty from a regiment in which he had barely served.

The military, however, would find out. It was nearly impossible to escape the trail of tedious paperwork that followed every volunteer.

The 110th eventually learned of Frazier’s desertion, and resolved the case in an unconventional way when a different man took his place.

That man was Hannibal.

How Hannibal became aware of the need to fill the gap left by Frazier is unclear. By some means, he met Theodore Bachly, who served in both regiments connected to Frazier. Bachly had served as a private in the 9th Mounted Infantry, and left the regiment to accept a second lieutenant’s commission in Company H of the 110th Colored Infantry. Bachly recruited Hannibal to replace Frazier.

Why Hannibal rejoined the army is an open question. He likely had no firm plans and, unwilling to return to South Carolina and seeing opportunity in the military, took a chance.

Hannibal left Illinois in July. There is no evidence that he and Addison Jackson ever communicated again. Jackson went on to a career as a watchman at the Treasury Building in Washington. Upon his death in 1895, his remains were interred in Arlington National Cemetery.

Hannibal made his way to Tennessee and joined the 110th at Gallatin. On Aug. 1, 1865, he enrolled using the alias Ransom Frazier. There is no record that dark-skinned Hannibal, who looked nothing like the tall and light-skinned Frazier, raised eyebrows with soldiers in Company H or its chain of command.

Hannibal’s tenure with the regiment ended in late October 1865, before he officially mustered in. He received a discharge due to cost-cutting measures by War Department officials seeking to reduce the burden of a large army on taxpayers. At the time, he suffered from pneumonia and other ailments in the post hospital at Huntsville, Ala.

Life after the war

Hannibal remained in Alabama after his discharge, working as a farm laborer in Athens, about 25 miles west of Huntsville. He had learned the basics of reading and writing during his time in the army as part of an effort to educate freedman to be good citizens, and supplemented his knowledge at night school. He married Rosetta Malone and they started a family that grew to include six children, three of whom survived to adulthood. About 1885, they moved to Woodruff County in Arkansas and settled into sharecropper’s lives on a farm outside Augusta, 80 miles due west of Memphis. Rosetta died soon after they arrived, leaving Hannibal a widower.

He applied for a military pension for his service in the 12th to supplement his earnings and support his three young children. Government examiners soon discovered his relationship to Ransom Frazier and the 110th. They launched an investigation in 1886. One of the agents noted that for the second time in as many months, he had been assigned a case involving a missing soldier in the 110th who had had his place taken by another man, and who answered roll call under the name of the absent man.

After a flurry of affidavits to surface facts and connect the dots, examiners awarded Hannibal his pension on the basis of his service as an under cook in the 12th. They took no punitive action against Hannibal or Frazier.

In 1887, Hannibal married Mary Madora McLauren, a Tennessee-born woman about 14 years his junior. They brought eight children into the world, and four of them lived to maturity.

Around the turn of the century, the family relocated from Woodruff to the Lee County community of Moro. They lived there for the rest of their days. Hannibal suffered from rheumatism and chronic lung problems. He died Feb. 12, 1912, due to complications after suffering a rupture. He was 63. Mary passed eight years later.

Note: Today, the adjectives Scottish or Scot(s) are preferred over Scotch.

Special thanks to Sheila Vaughan and Jim Quinlan for accessing

Hannibal’s pension file at the National Archives, and to Randy Beck for his encouragement.

References: The Camden Confederate, Feb. 8, 1865; Buffalo Courier, N.Y., Feb. 25, 1865; Hannibal Turner military service record and pension file, National Archives; Addison A. Jackson military service record, National Archives; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 12, 1895; Reece, Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Illinois containing Reports for the Years 1861-1865: Volume 1 — 7th-15th Infantry Regiments; 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedule; John F. Turner family records on Ancestry.com.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.