By Adam Ochs Fleischer

In this installment, we move to the Western Theater of the war to examine a backdrop used at Camp Hendershott in Davenport, Iowa, and likely in Rock Island, Ill., by photographer Charles S. Newberry. Though some questions regarding the backdrop’s use remain a mystery, my intuition is that they will someday be resolved. A wealth of photographic examples exist, increasing the likelihood of thorough documentation.

Location

The “Quad Cities” area, which includes the cities of Rock Island and Moline in Illinois and Davenport and Bettendorf in Iowa, cemented its shared identity during the Civil War. Situated along the Mississippi, they began as small river towns enriched by riverboat traffic. As the years went by, they shared in their mutual prosperity.

For Civil War enthusiasts, Rock Island looms particularly large, as its namesake, a large island in the Mississippi River at the center of the Quad Cities, became an important arsenal and prisoner of war camp in 1863. Upon its establishment in 1864, Chief of Ordnance Brig. Gen. George D. Ramsey wrote, “In a military point of view it is perfectly secure from an enemy advancing either by the lakes or the river. From it supplies can be transported in any direction and at any season of the year. It is in the midst of a country teeming with coal and wood, and especially adapted to agriculture. The site is elevated far above river floods, the climate and situation are healthy; and while the Island is sufficiently located to secure it from sudden attacks, it is near enough to the cities of Rock Island, Davenport and Moline to afford ample accommodations for all the necessary employees.”

Davenport too was a military force in its own right. Shortly before the onset of hostilities the city was declared the state’s military headquarters, and it would later play host to a number of camps that organized and distributed Hawkeye soldiers.

The confluence of military and economic activity produced a maelstrom that enveloped the region. Thousands of soldiers were organized and mustered out, hundreds of prisoners of war came in, and the effects of civil war consumed the whole of the Quad Cities.

The Photographer

One enterprising man who took advantage of the economic opportunity presented by the influx of soldiers was photographer Charles S. Newberry. Born circa 1815 in New York, Newberry seems to have lived for a time in Kentucky and Wisconsin before arriving in Rock Island in the 1850s. Though listed as a “painter” as late as the 1860 census, an 1844 article in the Rock Island Argus claims him as Rock Island’s first photographer. This is unlikely, as 1850s newspapers advertise photographers working in Rock Island with no mention of Newberry.

One enterprising man who took advantage of the economic opportunity presented by the influx of soldiers was photographer Charles S. Newberry. Born circa 1815 in New York, Newberry seems to have lived for a time in Kentucky and Wisconsin before arriving in Rock Island in the 1850s. Though listed as a “painter” as late as the 1860 census, an 1844 article in the Rock Island Argus claims him as Rock Island’s first photographer. This is unlikely, as 1850s newspapers advertise photographers working in Rock Island with no mention of Newberry.

Regardless, Newberry was undoubtedly working as a photographer by 1862, as evidenced by carte de visite photographs taken by him at the short-lived Camp Hendershott military base (1862-1863) located in Davenport. If Newberry’s experience at Camp Hendershott was his first stint as a commercial photographer, it must have been a success, as he continued working as one until his death in 1882. Newberry’s professional triumph seems to be a series of stereoscopic views he produced as the “Western View Company” in the 1870s, which are still used and reproduced today.

Where was the backdrop?

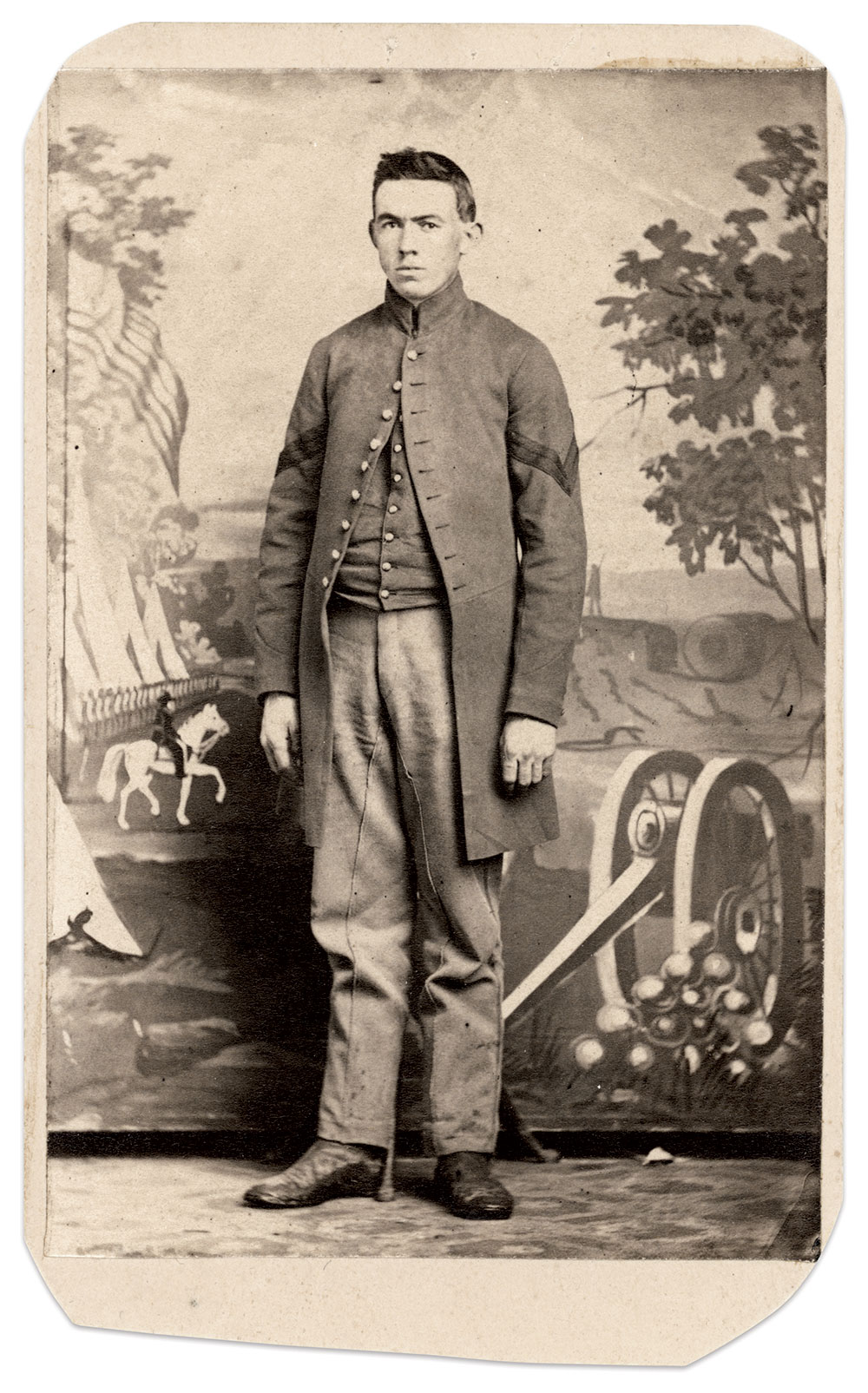

The “Cavalry and Cannon” backdrop was used, without any doubt, by Charles S. Newberry at Camp Hendershott in Davenport. Named for Col. Henry Bascom Hendershott (1824-1906), West Point Class of 1847 and commandant of the U.S. Arsenal at Rock Island, the camp existed from October 1862 to August 1863.

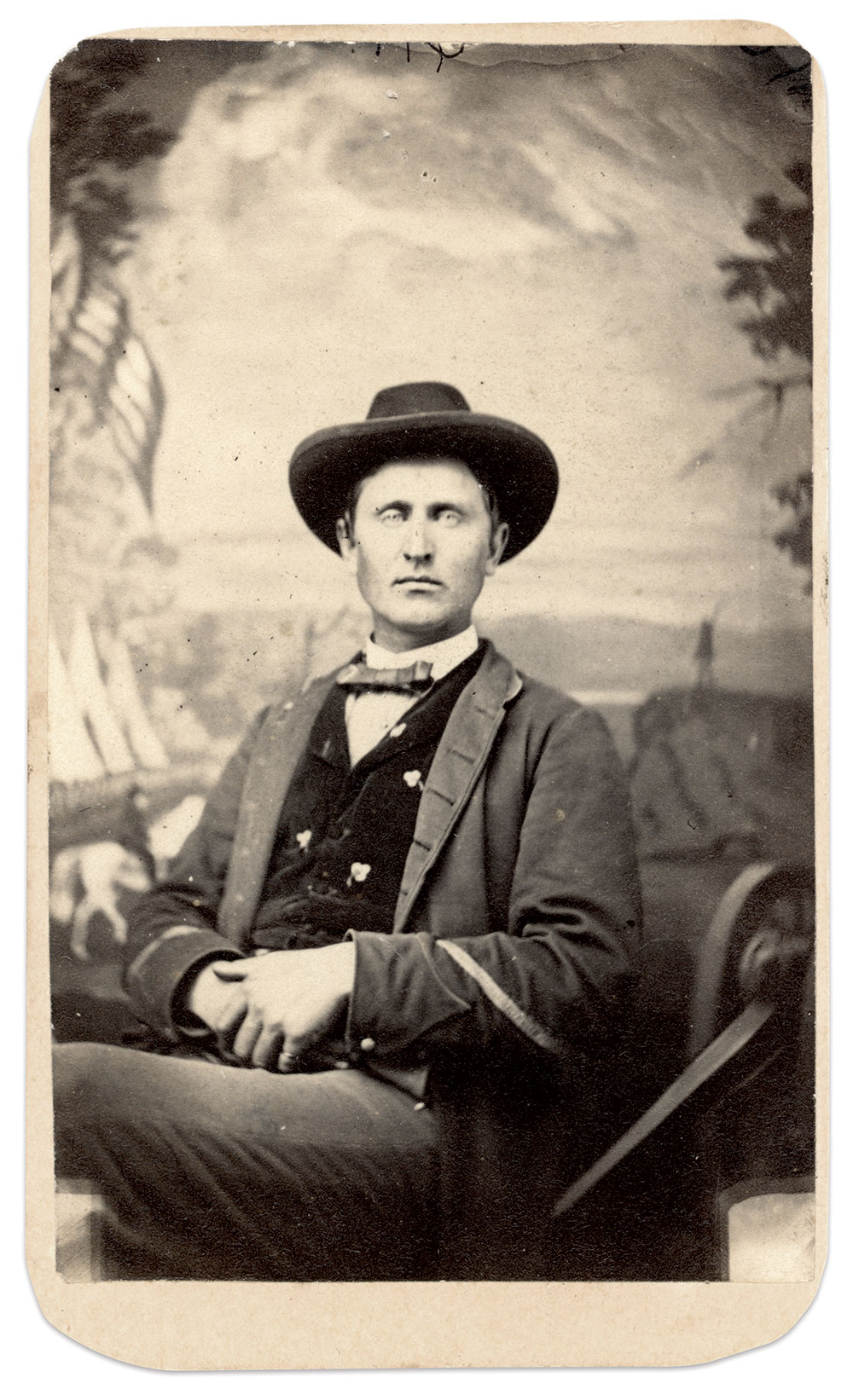

Numerous cartes de visite survive that bear Newberry’s imprint and show the backdrop. Though three Iowan cavalry units (the 6th, 7th, and 8th) organized at Camp Hendershott, some of Newberry’s photographs bearing the Camp Hendershott imprint feature the backdrop, but do not feature cavalry soldiers. This suggests that soldiers came to Newberry’s studio from Davenport and the greater area to have their portrait taken.

After Camp Hendershott closed in the summer of 1863, Newberry returned to Rock Island to take portrait photographs of soldiers alongside a business partner with the surname Cook. A few examples of their work survive, but not many. Newberry may also have briefly partnered with someone with the surname Peck. Evidence suggests that the Cavalry and Cannon backdrop was used after Camp Hendershott closed, so tintypes and cartes de visite with the backdrop but without a Camp Hendershott imprint can also be tentatively attributed to Newberry’s studio in Rock Island.

The backdrop

The Cavalry and Cannon backdrop’s aesthetic style is similar enough to a backdrop variation used at Benton Barracks in St. Louis that it makes one wonder if the same artist is responsible for both. St. Louis and Rock Island are not especially close to each other, but both cities were located on what was then the edge of the western frontier. Perhaps there was a regional production firm that made both examples.

Special thanks to Michael Huston and Pat Smith for making the

photographer’s imprint available.

Adam Ochs Fleischer is a passionate researcher of Civil War photography and an admitted image “addict.” He began collecting in high school and quickly became obsessed. He lives in Columbus, Ohio.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.