By Kurt Luther

In 2020, the Smithsonian Institution released nearly three million digital images of its collections for the public to download freely and view online. These included more than 5,000 Civil War-era portraits from the National Portrait Gallery’s Frederick Hill Meserve Collection. The photos, a mix of studio and documentary photos, are glass negatives primarily attributed to Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner. Many are identified, but some only partly identified with surnames (e.g., “Fairchild,” “Lieutenant Rankin”) or completely unidentified. Often, these negatives can be matched to identified prints or variant poses in other public collections such as the Library of Congress and National Archives. Thus, they offer fertile grounds for photo sleuthing, and I have enjoyed researching them over the past couple of years.

One unidentified photo in the Meserve Collection, a group portrait of federal soldiers in the field, caught my attention. It lacked any obvious counterparts in other collections to help identify it. Yet, it also contained numerous enticing clues suggesting that a focused research effort would pay off. In this column, I show how genealogical and military research helped uncover a new photo of a Civil War soldier whose sacrifice and legacy haunt the halls of government more than a century later.

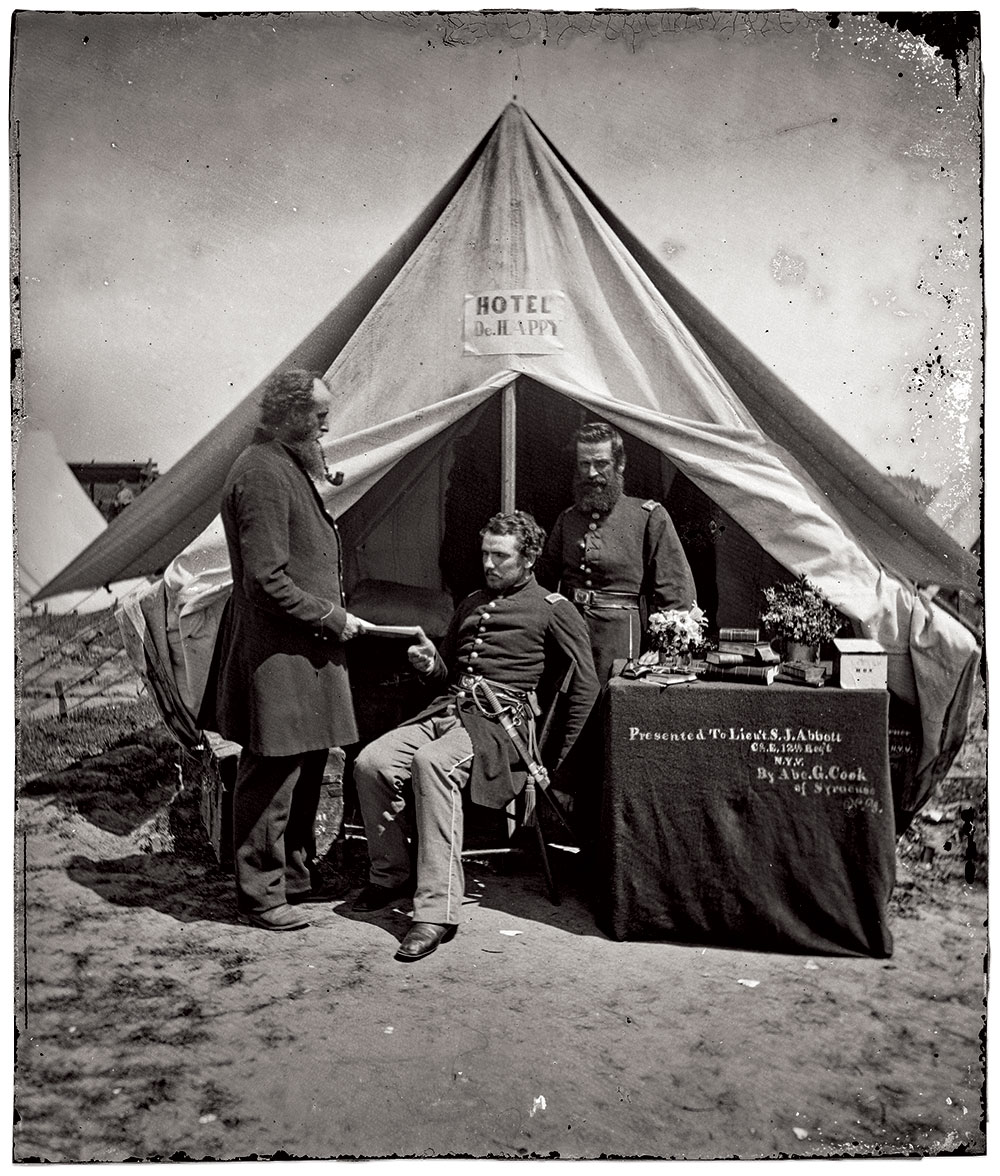

The photo shows three Union soldiers outside an officer’s tent. In the center of the composition, a young, curly-haired man wearing a frock coat, second lieutenant’s straps, sash, sword and scabbard sits in a wooden chair. He accepts a document proffered by a standing soldier who, with a balding head, graying beard and tobacco pipe, looks older than his private’s rank would suggest. Behind the seated man, an older officer with a thick beard and first lieutenant’s straps stares at the camera rather than the exchange taking place in front of him. Both officers’ belts feature the New York buckle with script letters “NY” enclosed in a wreath.

The setting of this photo, apparently taken in the field yet elaborately staged, reveals intriguing details. Several other tents and a soldier leaning against a wooden structure suggest the scene takes place in a semi-permanent encampment. An amusing sign with the caption “Hotel De. Happy” is posted above the tent flap. Outside and in front of the tent, a trunk bears a partially visible inscription “-tt” and “g’t.” A table covered with an inscribed tablecloth and an assortment of objects, including a pile of books, vase flowers, pen and inkwell, and a pistol, evokes a still life painting. The tablecloth inscription reads,

Presented To Lieu’t S. J. Abbott

Co. E, 12th Reg’t

N.Y.V.

By Abe. G. Cook

of Syracuse

N.Y.

Inside the tent, a second foot officer’s sword and scabbard lie on a cot to one side, while a second trunk with a partially visible inscription of “-rner” and “N.Y.V.” occupies the other side.

Who were these men, and what did their tableau mean? The National Portrait Gallery’s item description provides limited information. The caption reads simply, “Civil War Camp Scenes / Possibly New York 7th Regiment.” Since the standing private lacked the 7th NYSM’s distinctive enlisted uniform and the officers’ trousers had a single stripe on each pant leg, I ruled out that theory. The photo is attributed to Mathew Brady’s studio, and all three subjects are described only as “Unidentified Man.”

The tablecloth inscription struck me as the obvious place to start investigating. I searched New York soldiers with the surname “Abbott” and first name “S*” on the American Civil War Research Database (HDS) and found eight results. (The asterisk * allows for a wildcard search matching any letters.) Only one was an officer, and I was happy to see that his middle initial and military record matched the inscription. Samuel Junius Abbott, age 27, was commissioned second lieutenant of Company E, 12th New York Infantry, on May 13, 1861, at Salina, near Syracuse, New York. He was promoted to first lieutenant on August 3 of that year, and resigned about a month later, on September 19.

Lt. Abbott’s military service was short but eventful. After joining the 12th New York, Abbott and his men traveled to Washington, D.C., and set up camp on Capitol Hill. A few weeks later, the regiment was placed under the command of Irvin McDowell’s Army of Northeastern Virginia and marched towards Richmond in the Manassas campaign. At the Battle of Blackburn’s Ford on July 18, Israel Richardson’s brigade, including the 12th New York, faced off against James Longstreet’s brigade while trying to cross Bull Run near Centreville, Va. Under heavy fire, the New Yorkers

fell back.

The 12th’s disorderly retreat proved controversial. The regiment’s colonel, Ezra Walrath, was accused of cowardice and incompetence. A court of inquiry exonerated him months later, but the damage was already done. Over half the regiment had already deserted, according to a newspaper account unearthed by Harry Smeltzer. Walrath stepped down and was replaced.

Other men of the regiment made better impressions that day. Two members of Company K, Cpl. James Cross and Pvt. Charles Rand, later received the Medal of Honor for standing firm. Captain Henry Barnum of Company I later wrote that Abbott and his fellow company officers, 1st Lt. Frederick Horner and Capt. Jabez Brower, “tried to prevent their men from breaking, and followed them only to attempt their rally.” Abbott and Brower then “came back [to the front], but were so overcome with the excessive heat and fatigue that they had to be assisted from the field.”

Lieutenant Horner, who remained behind, was apparently in even worse shape. A few weeks later, on July 30, he resigned for health reasons, declaring himself “unfit for duty.” Abbott promptly replaced him as Company E’s first lieutenant in early August. However, the following month, after the 12th New York had encamped at Fort Craig in Arlington, Abbott also resigned for health reasons, citing “disability arising from continued sickness.”

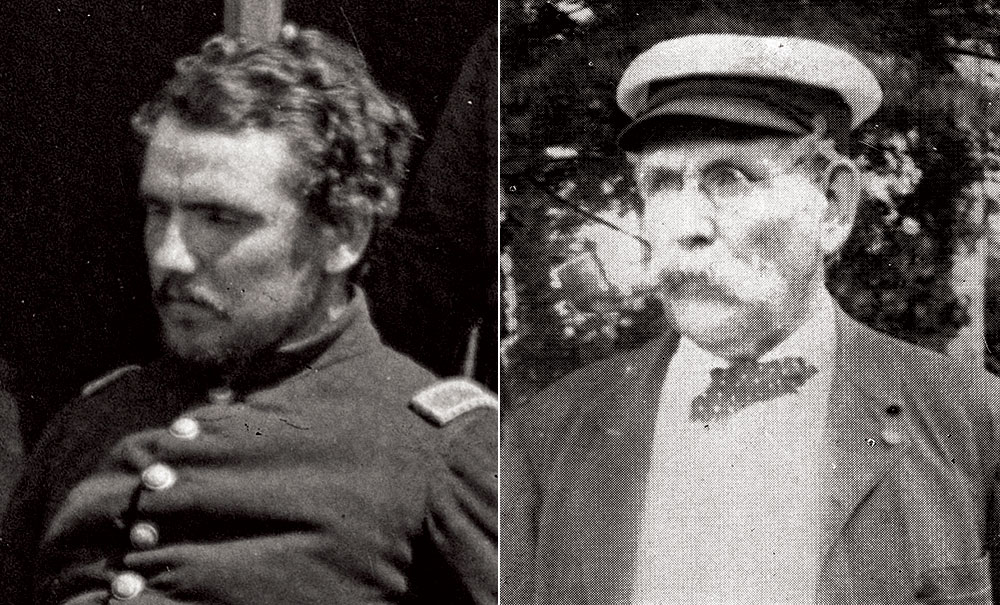

Having studied the military service of Lt. Samuel Abbott and his comrades of the 12th New York Infantry, I felt confident that one of the three men pictured is Abbott. The man seated beside the eponymous tablecloth, the focal point, is the clear choice from a compositional standpoint, but we can firm up the identification by comparing other visual clues to the biographical records. Of the three men, only the seated one appears young enough to be Abbott, age 27 in 1861. He also wears the rank insignia of a second lieutenant, which we know Abbott held for most of his service. The trunk on the left with partially visible lettering “-tt” – that is, “Abbott” – may hold his personal effects.

After establishing Abbott as the seated man, I next considered the unknown officer standing behind him. I propose that this officer is Frederick Horner. Horner joined the 12th New York at age 42 as Company E’s original first lieutenant. The standing man fits both age and rank. Further support comes from the trunk on the right, whose partially visible lettering “-rner” may represent the surname “Horner.”

The third man will be challenging to identify. Unlike the officers, he is a private, substantially reducing the odds of locating an identified reference photo. Few wartime reference photos of the 12th New York survive today in public collections; I could not locate any of Abbott or Horner in the New York State Military Museum’s prodigious collections, in HDS or the MOLLUS-Mass collection, on the Civil War Photo Sleuth website, or elsewhere. The unknown private also stands in profile, limiting the facial detail available for a confident comparison.

A final clue worthy of investigation is the second name on the tablecloth: Abe. G. Cook. Using the aforementioned wildcard technique, I searched the surname “Cook” and first name “Abe*” on HDS. Once again, I was pleased to find a single result. Abel Gay Cook was commissioned major of the 149th New York Infantry in September 1862, serving his regiment faithfully until a gunshot wound to his left foot at Chancellorsville necessitated his medical discharge in early 1864. But what was his relation to Samuel Abbott?

Requesting Cook’s pension records at the National Archives, I soon found a familial connection. Cook married Samuel’s sister, Henrietta E. Abbott, at a ceremony in Syracuse on May 27, 1862. Thus, in 1861, Samuel Abbott and Abel Cook were not yet brothers-in-law, but soon to be. The exact circumstances under which they met can only be guessed, but one possibility revealed itself in the 1860 US Federal Census records on Ancestry.com. Both men lived in Syracuse and reported their occupations as “Clerk.” Perhaps they were co-workers in the same local business, catalyzing a friendship and Cook’s fortuitous introduction to Henrietta.

Finally, I sought to fit the puzzle pieces together and draw a conclusion about the meaning of the photo’s tableau. We know that Brady and company photographed Civil War camp scenes around Washington throughout the spring and summer of 1861 (see Jeff Rosenheim’s excellent article in the previous, Spring 2022 edition of MI). However, the arrangement of figures and objects in the photo suggests one of two key moments in Abbott’s relatively short military career. One option is shortly after Abbott arrived with the 12th New York in May 1861 and camped on Capitol Hill. The second possibility marks his promotion to first lieutenant following Horner’s resignation in early August of that year in Arlington.

Abbott’s long career in public service had a tragic end. After his resignation, he returned to Salina, and was appointed postmaster of that place in 1867. That same year, he married Jane Utting, and the couple raised a family. Abbott was active in the local Grand Army of the Republic post, and worked in the Office of the Overseer of the Poor for nearly two decades. When Jane died from typhoid in 1895, he moved in with Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Behan, described as “life-long friends.” When Abbott was promoted in 1861, it was Behan who replaced him as second lieutenant of Company E.

Abbott took a job as night watchman for the New York State Capitol in Albany. On March 29, 1911, around 3 o’clock a.m., the Capitol building caught fire, and the entire building, including the priceless collections of the State Library, was lost. Samuel Abbott perished trying to save the records, the only human casualty of the fire. In subsequent decades, his sacrifice was remembered mainly as a ghost story told by employees and tour guides of the State Capitol.

In 2017, two New York state legislators, Catharine Young and Patricia Fahy, sponsored a law to honor Abbott with a plaque installed in the Capitol. The law, which required that the plaque include “a likeness of Samuel J. Abbott,” passed. The elderly Abbott commemorated on the plaque, with his bushy mustache, distinctive ear shape and twinkling eyes, nevertheless bears a strong resemblance to the young lieutenant in the mystery photo. With the discovery of this previously unknown wartime photo of Abbott in the National Portrait Gallery, we have a new way to remember his life of service and sacrifice.

Kurt Luther is an associate professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor at Virginia Military Institute. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits. He is an MI Senior Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.