By David B. Holcomb

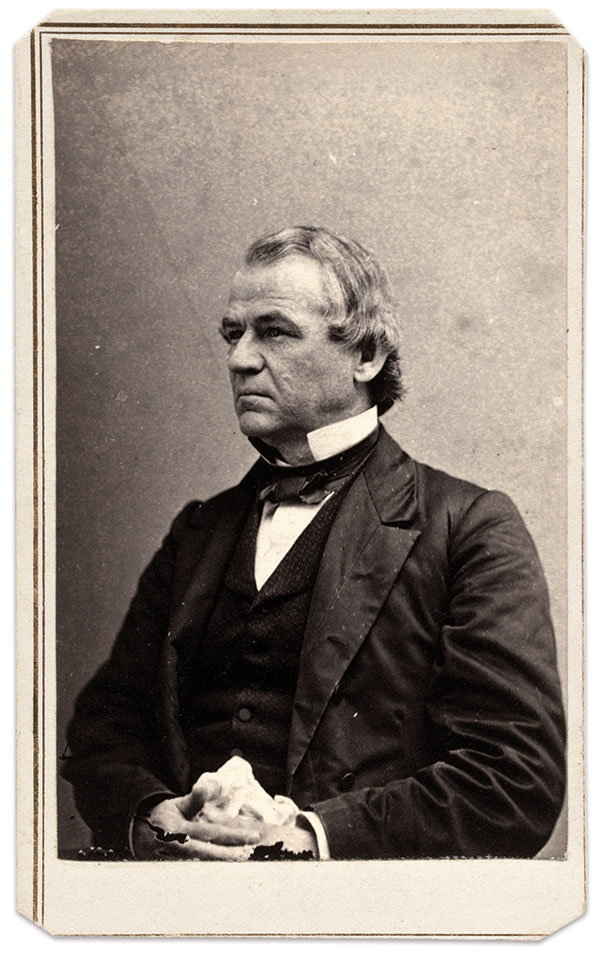

Lafayette Curry Baker was a scoundrel, a striving, uneducated bully who never lacked for self-confidence or hesitated to tell a lie. Yet, he rose to become the head of the federal intelligence service for the Union during the Civil War. He did so with not much more than street smarts, self-promotion and a huckster’s ability to spin a good yarn.

Baker preserved the account of his rise to become the nation’s spy chief by hiring a ghostwriter to compile his memoirs, History of the United States Secret Service. The book is notable for its exaggeration of Baker’s wartime service and his abilities to get the best of nearly everyone with whom he came into contact.

Baker’s journey began with his 1826 birth in upstate New York into a farm family who moved to Eaton County, Mich., when he was 13. Lafe, as he was called, had little interest in school. Following the death of his father in 1847, Baker worked in New York and Philadelphia until about 1853, when a brother lured him to San Francisco with stories of gold and wealth. He did not find a fortune, but he did discover a talent for knocking heads and street fighting as a member of the Committee of Vigilance. When this organization dissolved, he joined the police force in San Francisco, and later worked as a license tax collector until New Years’ Day in 1861, when he booked passage on a fast clipper and headed back to New York.

Fantastical tales of espionage

By mid-April, Baker had left the Empire State for Washington, D.C., where he set his sights on securing a lucrative appointment in President Abraham Lincoln’s new administration.

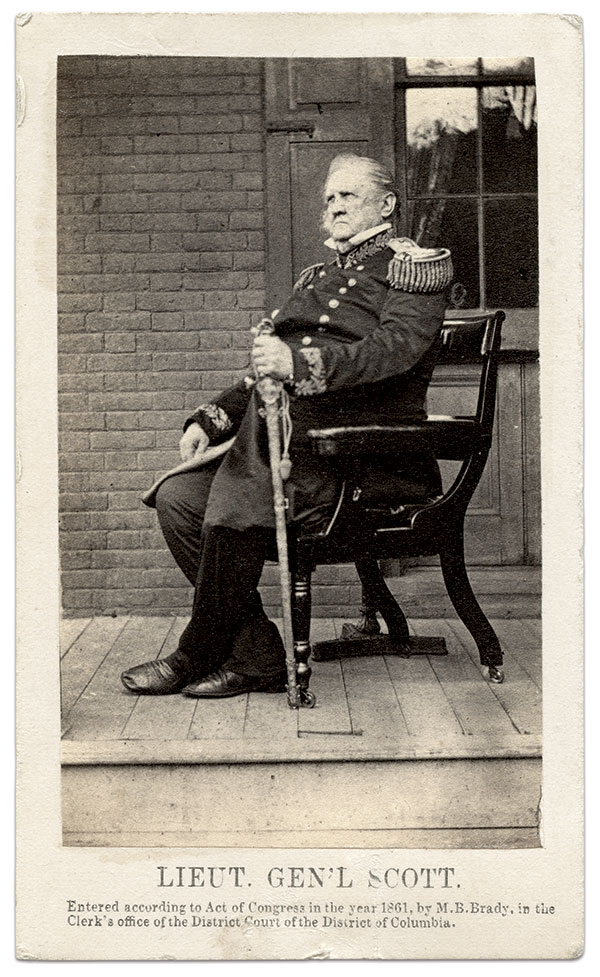

Baker wasted little time. Fueled by the start of the Civil War and his ambition, he sought out the army’s commander-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott. The hero of the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War was known as “Old Fuss and Feathers” for his passion for martial pomp.

Baker recalled how he talked his way into an introduction to Scott, and curried his favor with tales of his “experiences as a detective and the services required to ascertain the strength and plans of the enemy.” Scott recognized the need for accurate enemy intelligence.

As Baker tells it, Scott sent him to the rebel capital, “to learn, if possible, the locality and strength of the hostile troops.” Thus begins a tale of precarious spots and narrow escapes that blur the lines between reality and exaggeration.

His fantastical accounts includes Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard, the rebel spy Belle Boyd, Jefferson Davis, Confederate soldiers and cavalrymen, provost marshals and enslaved people. They include at least three daring escapes from sleepy or drunk Confederate cavalrymen or soldiers; a river crossing while dodging a hail of bullets; outsmarting the Confederate president during a series of interrogations; a prison break using a knife conveniently overlooked by prison guards; and bribes paid with gold coins.

Throughout the memoirs, Baker is the quick thinking and fast-talking protagonist who always outwits his adversaries.

At least three editions of the book were published and none contain the same stories. Author Edwin C. Fishel, in his 1998 book The Secret War for the Union, The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War, notes, “This easy interchangeability of contents suggests that Baker did not regard the book as a serious contribution to history – which helps explain the scores of stretchers and complete fiction.”

Though Baker’s tall tales cannot be taken seriously, they cannot be dismissed entirely. Official documents support the general outline of his adventures.

The story of Gen. Scott is a case in point. According to Fishel, “The record that supports his claim is sketchy but authoritative. It consists of his bill for $105 in expenses, naming Manassas and Richmond as the points visited, citing General Scott’s orders as authority for the mission, and bearing endorsements by Secretary of State Seward and a disbursing officer of the War Department.”

Baker used these documents in 1861 to convince his superiors that he had been in Manassas and Richmond. But details added by him in his memoirs should not be taken at face value. Baker was likely arrested while in Manassas and Richmond, and questioned by Confederate officials. It is however extremely unlikely that Gen. Beauregard and President Davis interviewed him, or that Confederate troops were drunk, sleepy, or careless.

Scott’s version of events is missing, as no report by him has been found, and he died in 1866.

War Department shenanigans

In the first of a series of transfers, Baker moved to the War Department and reported directly to its new Secretary, Simon Cameron. Baker did not last long in this post because Lincoln quickly lost confidence in Cameron’s ability to administer his office efficiently and honestly.

Lincoln transferred Baker and other internal security to Secretary of State William H. Seward with a mandate to root out treasonous elements in the government. Seward and Baker took to the task with such enthusiasm that the jails soon filled with both Republicans and Democrats. When they cried foul, Lincoln’s support waned. Lincoln promptly transferred internal security back to the War Department and Cameron’s replacement, Edwin M. Stanton. A former attorney general in President James Buchanan’s administration, Stanton worked himself to exhaustion cleaning up the graft and waste that plagued Cameron’s brief tenure.

While Stanton considered Baker’s fate, Lincoln signed Executive Order No. 1 on Feb. 14, 1862. It granted amnesty to political prisoners detained in the initial wake of the insurrection, provided they signed a parole. The order also empowered the War Department to continue to pursue spies, effectively making Stanton a security czar. The next day, Stanton received a glowing recommendation from Seward regarding Baker.

Stanton decided to keep Baker, who lost no time establishing a force of some 30 full-time detectives, bringing over some of the agents he had directed in the State Department. Baker likened his growing force to a type of a national or international secret service.

Baker’s grand vision fueled frustrations in having to report to others. He also objected to not having been given a formal title — so he invented his own. He sometimes referred to himself as “Special Provost Marshall” or “Chief of the National Detective Police Department.” He hung a plaque in his office proclaiming “Death to Traitors,” which might be interpreted as a nod to the agents’ relentless pursuit of disloyal individuals. In practice, the detectives and their method of terrorizing suspects in the South and North resembled his former San Francisco vigilantes. They spent most of their time chasing horse thieves, smugglers, draft dodgers, crooked contractors and counterfeiters, rather than on cloak-and-dagger work.

Spy vs. spy

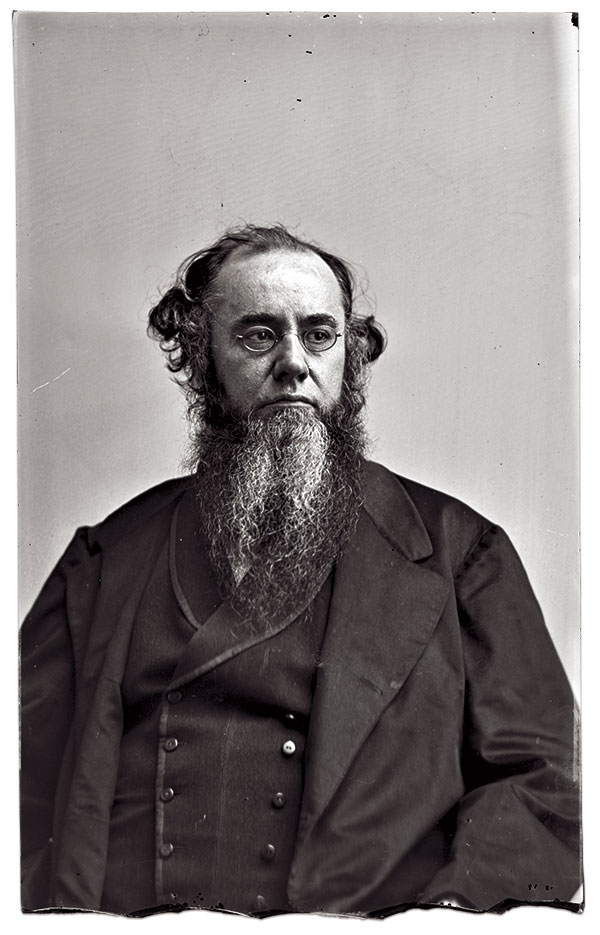

Baker and his detectives represented one of two secret services operating under the auspices of the Lincoln administration. The other group, led by Allan J. Pinkerton, reported to Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, commander of the powerful Army of the Potomac. As Lincoln and McClellan famously did not get along, neither did Baker and Pinkerton. They viewed each other as incompetent rivals, and did not share information or coordinate efforts. Both spied on each other, and developed intelligence to undermine each other’s organization.

One particularly egregious example involved Stanton’s effort to discredit McClellan for the inaction of the army he had built but proved unable or unwilling to use. Pinkerton’s inflated estimates of Confederate troop numbers heightened McClellan’s innate caution. Baker and his agents, under Stanton’s direction, uncovered McClellan’s various missteps and reported them to the press and to the President.

Historian Mark C. Hageman of the Signal Corps Association summarized the situation: “Since Pinkerton was the espionage chief serving McClellan, the more mistakes the Union Army made, the more blame could be shifted to Pinkerton who was apparently not providing the kind of intelligence that would allow McClellan to make decisive military moves.”

McClellan’s performance in 1862 lends credence to the Stanton-Baker narrative. McClellan’s caution throughout the months long Peninsula Campaign and his lackluster command at the bloody Battle of Antietam raised questions about his ability to lead a large army.

McClellan defended his generalship at Antietam, arguing that he prevented Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia from achieving broader goals of a northern invasion and foreign recognition of the Confederacy. The Pyrrhic victory at Antietam was not all Lincoln had desired. But it was enough for him announce his intention to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which he had been waiting to release on his cabinet’s advice following a military victory.

McClellan also dispatched Pinkerton to Washington to spy on Lincoln, no doubt wondering if his reputation had suffered in the president’s eyes. Lincoln turned the tables on Pinkerton by pumping him for the details of Antietam, and then used this information to push McClellan to become more aggressive with his army. The iconic photograph by Alexander Gardner of a stiff Lincoln meeting with the vainglorious McClellan inside the general’s command tent underscores the tension between the two men.

Despite Lincoln’s exhortations to make haste, McClellan tarried. The president removed McClellan from command, and Pinkerton severed his connection with the Army of the Potomac.

Baker and Stanton had won the Pinkerton-McClellan war.

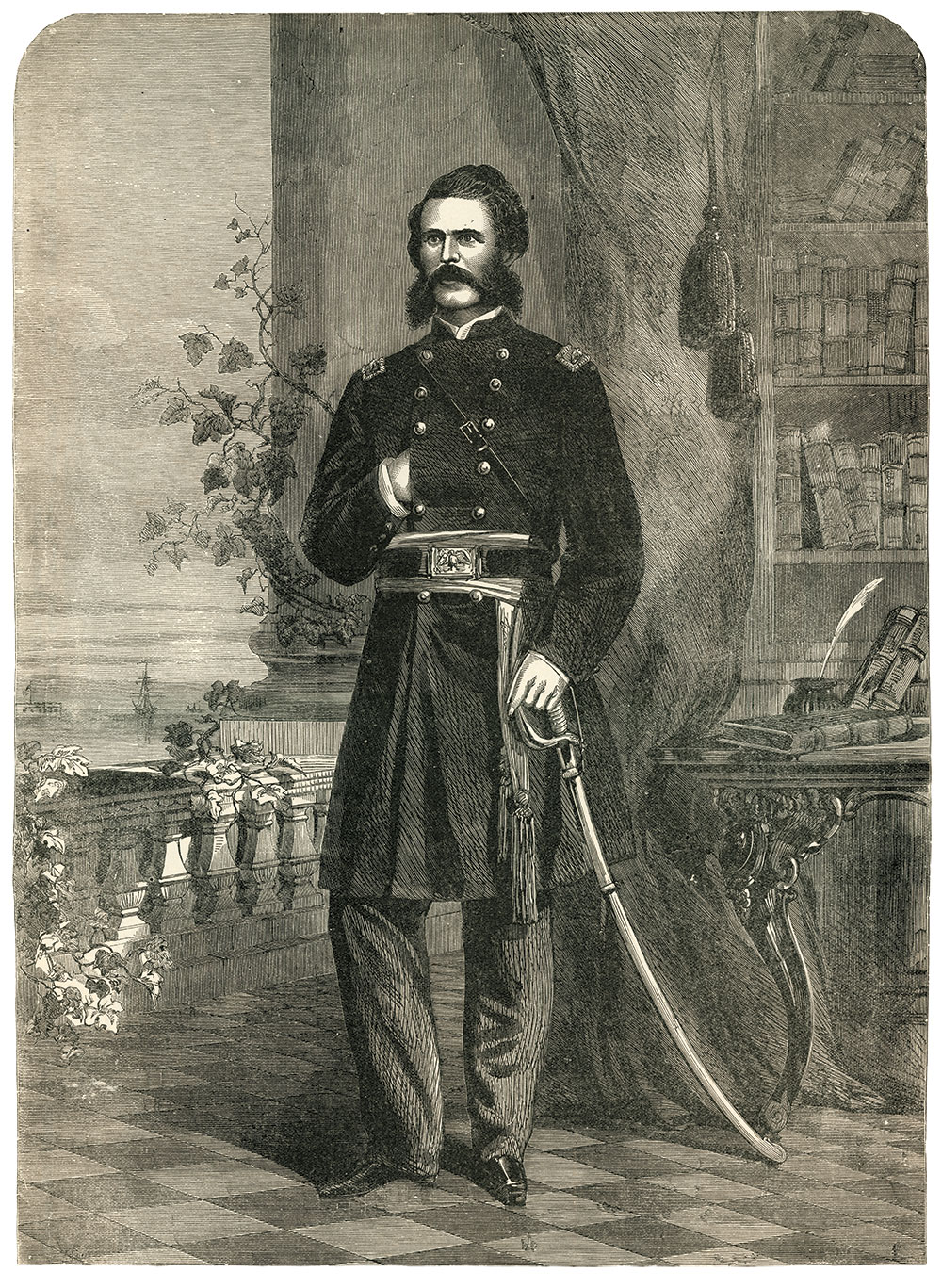

Colonel Baker’s independent cavalry

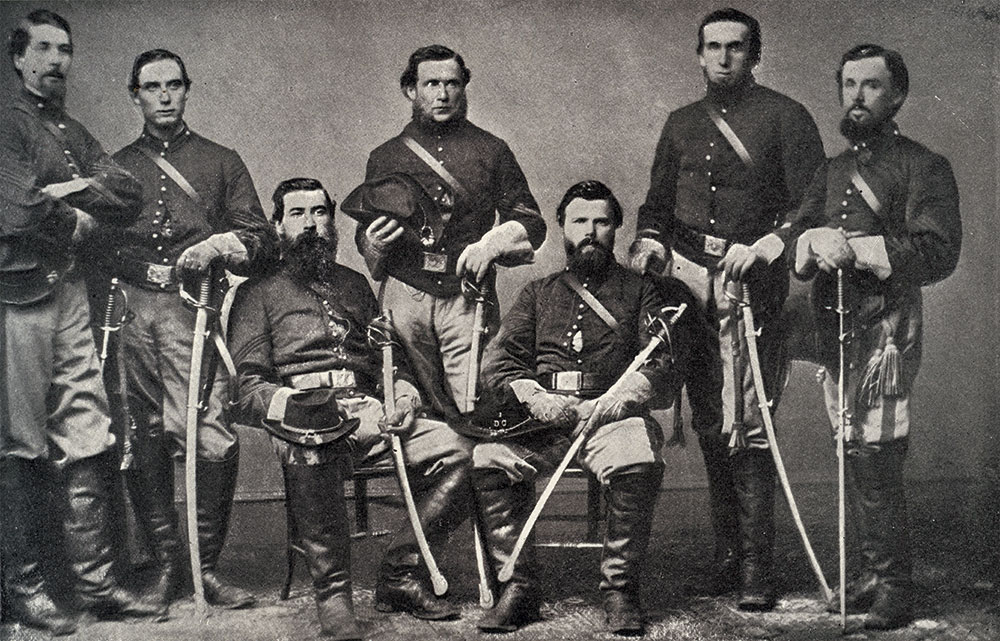

Flush with victory, Baker moved to enlarged his organization, authority and prestige in 1863 as the Eastern armies battled at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. He had a particular scheme in mind: The creation of an independent cavalry unit to root out subversives and defend Washington from attack. Baker, of course, would be its commander.

Baker had long advocated the idea, and lobbied Stanton for it. Skeptics pointed out that cavalry was crucial in reconnaissance, and not the right tool for spying and espionage. Baker insisted the unit would be useful for raids. Stanton ultimately authorized the request, along with a pair of colonel’s shoulder straps for Baker.

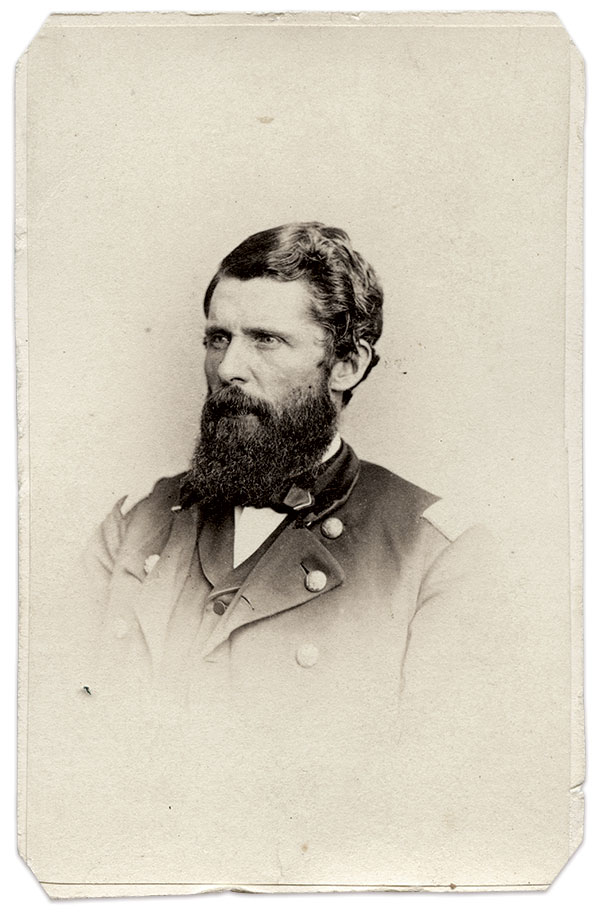

The First District of Columbia Cavalry, also known as Baker’s Cavalry, organized with four companies between June and December 1863.

Baker recounted with evident pride one of its early operations just outside the Defenses of Washington near Annandale, Va. According to his after action report dated Oct. 22, 1863, a detachment led by the capable Maj. Everton Conger clashed with a squad of Col. John S. Mosby’s raiders. In the fight, Conger’s troopers killed one and captured three, which were hauled off to the Old Capitol Prison. Baker added that Mosby’s men fessed up to hunting for government horses and sutler’s wagons.

The “Affair at Annandale” was typical of Baker’s approach to command. He showed up infrequently. When he did appear, he had the men fall in and stand at attention, and then made a short speech before leaving—unexpected behavior from the Baker, who once bragged that he wanted to be relieved of his duties as a spy so that he could lead his men into battle.

To his credit, Baker recruited able soldiers, bolstered by a New York Times story spun by Stanton that “honesty, sobriety and intelligence are required for service.”

As Baker’s Cavalry continued its raids outside the capital, senior military staff became concerned with what appeared to be un-coordinated and aimless sorties. Baker defended his cavalrymen from charges that they were, as described by Douglas Waller in his 2019 book Lincoln’s Spies, “a lawless bunch of vigilantes illegally confiscating property.”

Staffers’ suspicions were warranted. Baker lined his pockets as his men engaged in systematic looting. One favorite strategy involved raising spurious charges against innocent people and placing them under arrest so they could plunder their houses.

Word of Baker’s misconduct trickled up to Lincoln, and he expressed his concern in letters to Stanton. They had no effect. Protected by his champion, Stanton, Baker willingly ignored Constitutional rights. Although accused of significant wrongdoing, Baker evaded arrest, censure and dismissal due to a lack of solid evidence. Instead, Baker created evidence of wrongdoing against his accusers, effectively blackmailing them into supporting his corrupt espionage unit. “No one misused his authority or office more than Lafayette Baker,” Signal Corps historian Hageman observed.

Meanwhile, Baker turned his attention to other matters: Preventing contractor fraud, arresting deserters, disrupting corruption within the Quartermaster Corps and tracking down profiteers.

Baker left the cavalry to his cousin, Maj. Joseph S. Baker. The War Department promptly, and quietly, ended its independent status when it reassigned Baker’s Rangers to the Military Department of North Carolina and Virginia.

The War Department also issued orders for Baker to report to New York City on a limited mission to round up army deserters —effectively banishing him. The man behind the order was his former champion, Stanton. The secretary made the retaliatory move after discovering Baker had tapped his own telegraph lines on suspicion of corruption.

Manhunt mastermind

“Come here immediately and see if you can find the murderers of the president,” Stanton telegraphed Baker, without elaboration on the day Lincoln succumbed to his mortal wound. If the exiled spy chief interpreted the order as an appointment to lead the effort to find and capture the culprits, he was mistaken. Stanton summoned everyone he could think of to join the manhunt. However, Baker was not at the top of that list.

Baker booked a train for the next morning, April 16. He arrived in Washington in the afternoon, and reported to Stanton for duty.

Restored to command, Baker acted immediately by planting moles in the ranks of the investigators enlisted by Stanton. Baker correctly surmised that these investigators would not share information with him because of his well-deserved reputation as a publicity hound, and his tendency to run rough shod over his rivals. His moles provided the information that the prime suspect, John Wilkes Booth, and a suspected accomplice, David Herold, were traveling south through the eastern Maryland counties of Prince George and Charles. Thousands of troops and uncounted civilians became involved in the manhunt.

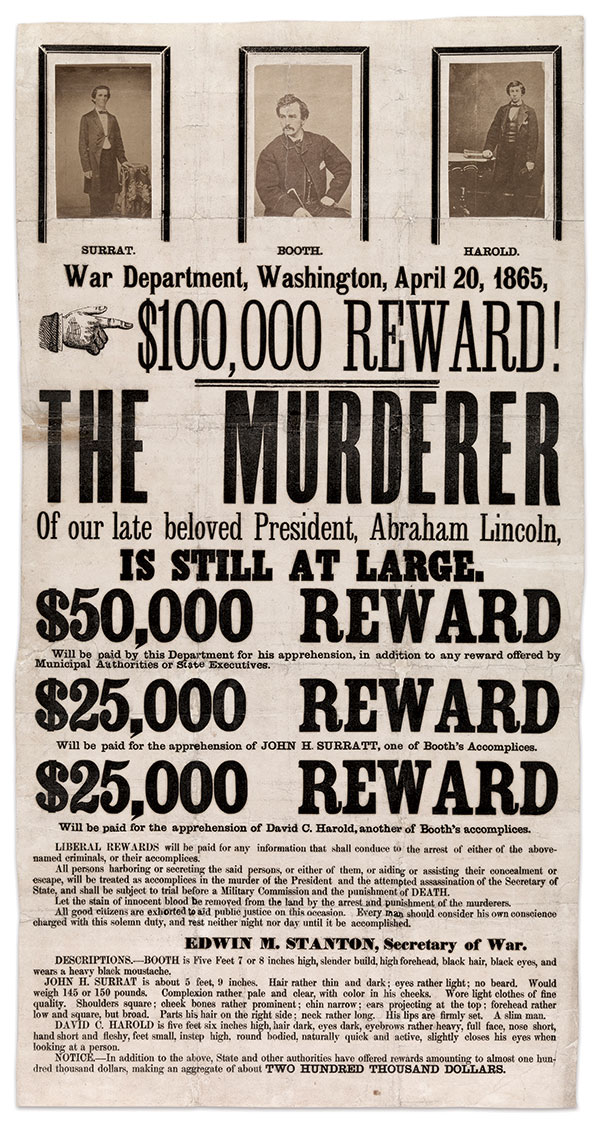

Baker utilized photography to assist in the investigation. He procured images of Booth, Herold, and another suspected conspirator, John Surratt, Jr. Baker had handbills printed with photos, descriptions and an offer of a $10,000 reward. More posters were printed when the reward increased to $30,000.

On April 21, the day that attendants loaded Lincoln’s body onto a funeral train bound for Springfield, Ill., Stanton increased the reward again: $50,000 for the capture of Booth, and $25,000 each for the capture of Herold and Surratt.

One hundred thousand dollars (about $1.8 million in 2022 dollars) was up for grabs. Every motivated civilian, detective, policeman, Union officer — and Baker — hoped to strike it rich.

Meanwhile, Baker’s critics considered him culpable in the events that lead to the president’s death. Following Pinkerton’s demise, some argued, responsibility for Lincoln’s security fell to Baker, who once bragged that he knew of every Confederate agent behind Union lines. In fairness to Baker, Lincoln thwarted efforts by anyone to protect him, complaining that it made him look like a preening Royal removed from the people.

In the end, Booth and his band plotted the assassination of the president, vice president, and the Secretary of State while freely roaming the streets of Washington.

The blame for this colossal intelligence failure must fall in large part on Baker. His intemperate bugging of Stanton’s telegraph line that resulted in his absence from Washington does not mitigate his responsibility. Indeed, that very act neatly sums up the cavalier and corrupt approach that Baker and his agents took toward their official duties.

On April 23, two days after the first reward posters appeared, Booth and Herold arrived at the tobacco farm of Richard H. Garrett in King George County, Va., following a harrowing journey through swamps and across the Potomac into Virginia’s Northern Neck with the aid of a Southern sympathizer and three ex-Confederate soldiers. Booth played the part of a wounded Confederate soldier for Garrett.

Back in Washington the same day, Baker happened to be in the offices of the War Department when he learned that two men identified as the fugitives had been seen making the Potomac crossing into Virginia. The details of report turned out to be inaccurate, for the men were not Booth and Herold. But the general outline of their travels sparked Baker’s imagination. He knew a great deal about the routes used by Confederate couriers and spies that operated in the Northern Neck, and made an educated guess as to where Booth and Herold might be.

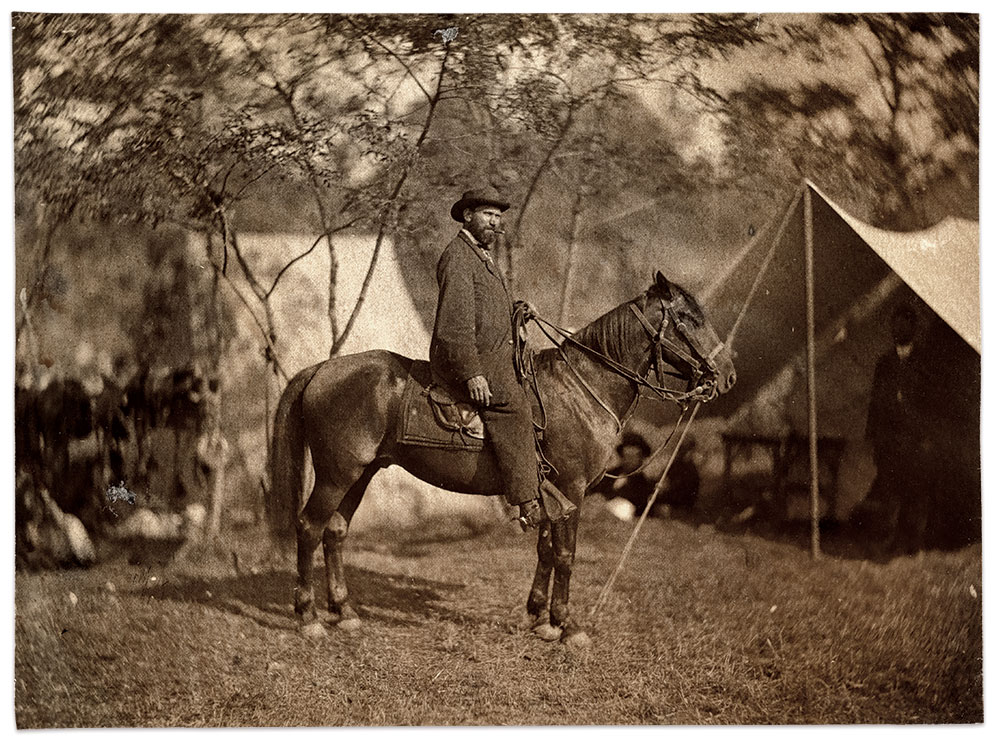

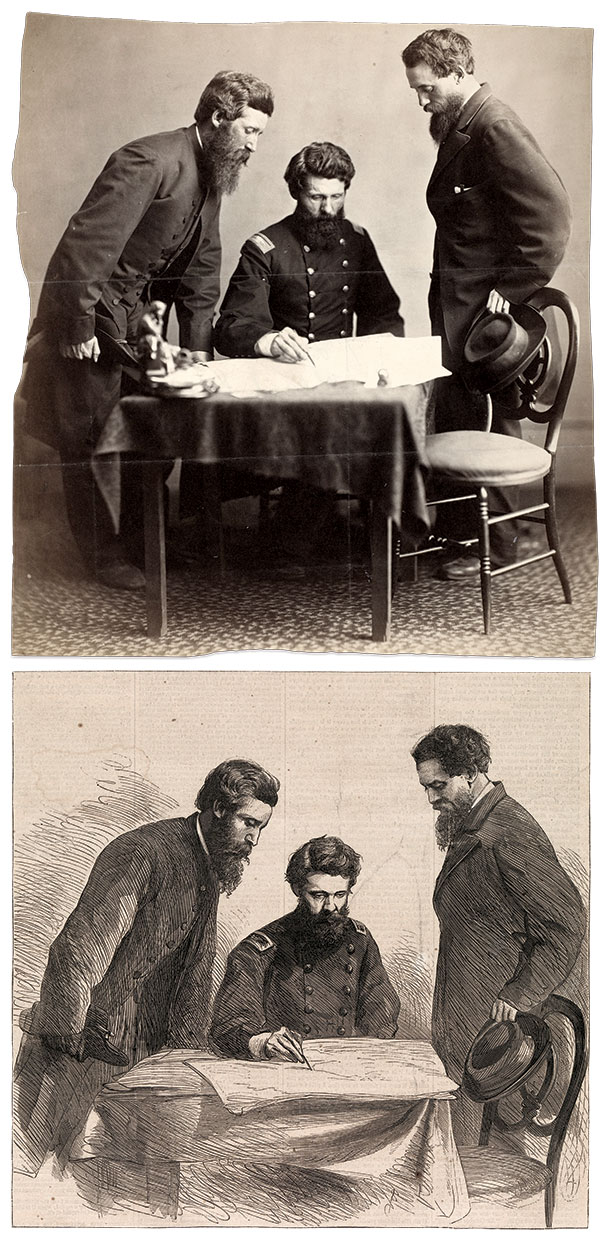

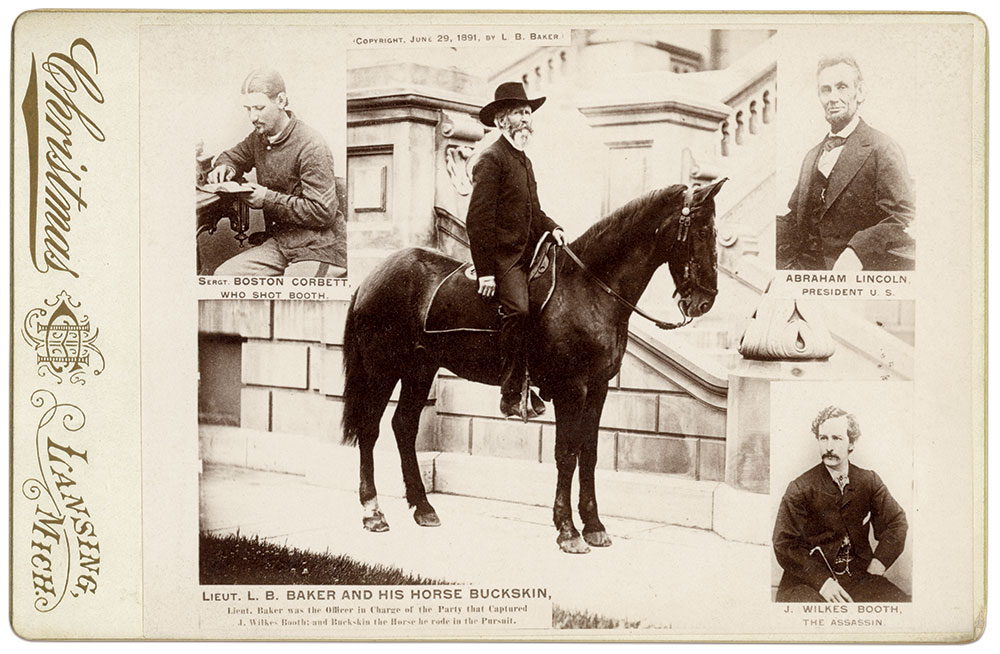

Baker acted on his hunch. He summoned his cousin, Luther Byron Baker, and Everton J. Conger to his headquarters. Veterans of his old cavalry command, both were assigned to Baker as detectives. Baker spread out a map on a small table and pointed to Mathias Point on the Virginia side of the Potomac. “He’s right in there,” Baker said, pointing to a circle he drew on the map. “I want you to go to this place, search the country thoroughly, and get Booth.”

Baker dispatched 25 volunteers of the 16th New York Cavalry, along with Luther and Conger, to Mathias Point via the government tugboat John S. Ide. The two detectives knocked on doors, and asked about two men, one with a broken leg, for 12 hours. Finally, Luther Baker learned about a recently returned ex-Confederate soldier who might know something. They found the former rebel and interrogated him at the point of Conger’s revolver.

The man guided them to Garret’s farm, where the cavalrymen discovered the fugitives in a barn. They surrounded the building and summoned Luther and Conger. Luther shouted to Booth and Herold that they had 15 minutes to surrender or, “I will burn this barn down!” Herold surrendered, but Booth remained defiant.

Upon the expiration of Luther’s ultimatum, Conger lit a fire at one corner of the barn to flush Booth out. Luther opened a door on the other side of the barn and peered inside. At that moment, Sgt. Thomas “Boston” Corbett, monitoring the situation through a gap in the barn’s siding, observed Booth approach Luther, who fired his revolver with deadly accuracy.

As Booth lay dying, Conger rode to Washington and found Baker in his office late in the afternoon of April 26. Conger reported that Booth had been killed and Herold captured. He also handed over Booth’s diary, and other personal effects from both men.

Baker scanned the diary and noted that it contained details of Booth’s flight from Washington after the assassination. He telegraphed the War Department that he would be at the city dock waiting for the return of the tugboat and its cargo of special prisoners.

Baker met the vessel and took custody of Herold and other prisoners suspected of being part of the conspiracy. He then marched them off to confinement. He also sent Booth’s remains off for an autopsy. Examiners identified the actor and assassin by a tattoo with the initials “J.W.B.” and a distinct scar on the back of his neck.

Baker had one more part to play in Booth’s final act. He took charge of the corpse, now decomposing and preyed upon by souvenir seekers, and whisked it away for a secret burial at Stanton’s request. Baker and Luther boarded a boat with the remains, and rowed several miles down the Potomac to the Old Arsenal Penitentiary (now Fort McNair). There, they off-loaded the body, packed it into an empty musket crate, and dumped it into a deep hole in an old cell. They filled the pit with dirt and replaced the original stone slabs.

National hero

Baker basked in the national spotlight for his role in the manhunt. The New York Times cast him as the mastermind of the operation. Stanton promoted him to brigadier general.

The positive notoriety bolstered Baker’s expectation that a grateful government would further recognize his efforts with the lion’s share of the reward money.

But other players also had legitimate claims. Conger considered himself the leader of the cavalry unit that found Herold and Booth. Luther made a case for his role in the capture. Edward P. Doherty, the lieutenant in command of the 16th New York Cavalry volunteers, proposed that they deserved the bulk of the reward, and that Conger and Luther only came along for the ride. In fact, there were hundreds of claimants, each with a story to tell.

Stanton turned the competing claims over to the military claims court. The court applied Navy regulations governing apportion of money for prize ships. Under these rules, the commanding officer received one-twentieth of the claim, and then awarded $3,750 to Baker from the remaining $75,000. Doherty, deemed the equivalent of a ship’s captain, received a tenth, or $7,500. Luther and Conger were awarded $4,000 each. The rest of the money was divided up among the volunteers of the 16th New York Cavalry (approximately $2,230 each).

Baker might have resigned to protest the paltry share of the reward money he received, but he remained in the War Department, restored to a degree in Stanton’s good graces.

Final fall from power

Baker’s bliss did not last long. Months into the administration of Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, Stanton split with the new president on Reconstruction policies. Johnson fired Stanton, and then turned his attention to Baker.

Johnson found much to dislike after being briefed on wartime accusations against Baker of graft and false imprisonment of his enemies. He grew suspicious that Baker diverted White House detectives to spy on him rather than to provide presidential security.

Johnson had Baker fired and mustered out of the military, ending his reign as spy chief. Baker departed Washington in February 1866 with a burning hatred of Johnson and Stanton, blaming both for sabotaging his career and stiffing him on the reward money. He hired a ghostwriter to recount his wartime services — the highly inflated 704-page History of the United States Secret Service. Baker hoped the book would boost his finances.

One year later, Baker returned to Washington for the impeachment of President Johnson. On Feb. 6, 1867, the House Judiciary Committee questioned its first witness — Baker.

Under oath, Baker told one tall tale after another, including the fanciful revelation that a traitorous Johnson shared military intelligence with Jefferson Davis. He added that he had evidence to prove it.

Baker could not make good on his claim, however. In fact, his testimony did more damage to his reputation than that of Johnson. Two Democrats on the House Committee summed up Baker’s performance: “It is doubtful whether [Baker] has in any one thing told the truth, even by accident.” Their Republican counterparts did not mention Baker in their report.

Baker moved to Philadelphia where, out of power and favor, he became a recluse. Weak book sales nagged at him. In the spring of 1868, he contracted typhoid fever and died in the early morning of July 3. He was 42.

Baker’s death certificate listed spinal meningitis as the cause. Conspiracy theorists claimed Stanton poisoned him to prevent the leaking of salacious state secrets.

The New York Evening Post published an editorial that succinctly summed up his life and times. “He was an adventurer, keen and unscrupulous and active. His services were probably thought necessary during the war, when Washington was full of spies.” The editorial concluded that Baker was ruthlessly efficient at suppressing insurrections but, “very often deceived by the rouges who it was his business to entrap; and kept in profound ignorance of really important plots, while he was excited by false reports. It will always be thus with the head of what is called a ‘secret police’ whose operations are likely to be secret to all honest people, but very transparent to the rogues.”

References: Fishel, The Secret War for the Union, The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War; Baker, History of the United States Secret Service; McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, The Civil War Era; Waller, Lincoln’s Spies; Greenhow, My Imprisonment and the First Year of Abolition Rule at Washington; Hageman, “Lafayette Baker, AKA: Sam Munson,” Signal Corps Association (civilwarsignals.org); Pinkerton, The Spy of the Rebellion; Hamilton and Ostendorf, Lincoln in Photographs, An Album of Every Known Pose; American Civil War Research Database (civilwardata.com); Miller, ed., The Photographic History of the Civil War; Dugard and O’Reilly, Killing Lincoln; Taylor, “Retracing the Steps of the 16th New York” (LincolnConspirators.com).

David Holcomb of Worthington, Ohio, has collected historic photography since the late 1970’s. He sold the bulk of his collection through Cowan’s Auctions in 1999 to raise funds for a commercial building and did not acquire a single image for 12 years as he raised his kids and built his business. In 2012, he returned to collecting with a focus on the Civil War, the Old West and fine daguerreotypes.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.