Second in a multi-part series of Abraham Lincoln imagery by MI Contributing Editor Chris Nelson, featuring photographs from the author’s collection

Abraham Lincoln’s face on the five-dollar bill and penny are most familiar to the world.

A third portrait, rarely seen today, was easily the most popular during the months following Lincoln’s assassination. Taken on Feb. 9, 1864, it pictures the President glancing down at a carte de visite album in his lap while his son, Tad, looks on. It arguably ranks as the most important Lincoln image next to the iconic portraits on currency and coin.

Mary Todd Lincoln included it in her carte de visite album. The vast number of surviving prints of her husband and son indicates that millions of other American inserted the same likeness into their parlor albums. It is a core image in Lincoln iconography.

It perhaps comes as no surprise that this portrait and the two better-known photographs were taken in Mathew Brady’s Washington, D.C., studio. Serious collectors know that Brady didn’t take any of them, although he and fellow entrepreneur Alexander Gardner deserve all possible praise for their essential role in recording and preserving the faces and scenes so important to our understanding of the war and its people.

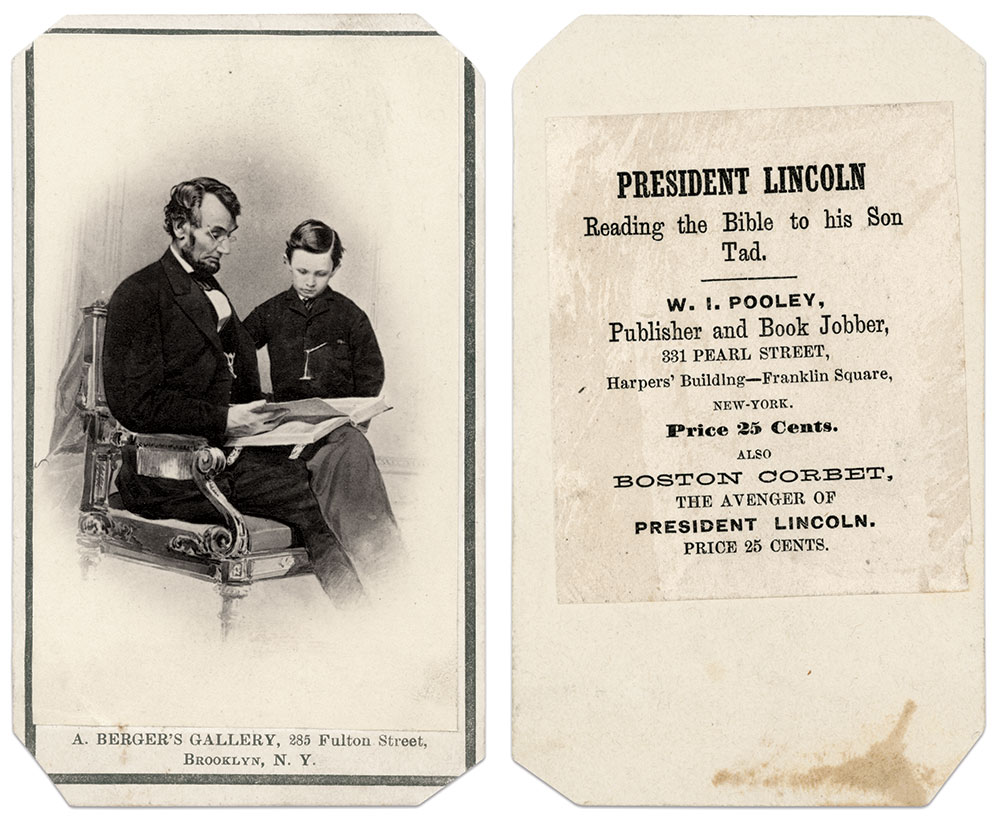

The man behind the camera for all three iconic shots happened to be a Brady employee: Anthony Berger (1832-after 1897). Born Anton Berger in Germany, he immigrated to the United States in 1854 and became a naturalized citizen in 1861. A self-described artist and gifted photographer in Brooklyn, N.Y., prior to the rebellion, he managed Brady’s gallery in the nation’s capital, and traveled to Gettysburg to take photographs days after the battle.

Berger’s charming, intimate look at the beleaguered wartime leader as a family man struck a chord with Americans in the wake of his assassination. “I think a father never loved his children more fondly than he,” observed U.S. Congressman William D. Kelly, a Republican from Pennsylvania who frequently visited the White House. “The President never seemed grander in my sight than when, stealing upon him in the evening, I would find him with a book open before him, as he is represented in the popular photograph, with little Tad beside him.”

Kelly made these comments in a speech following the assassination. This quote appeared in 1866 in artist Francis B. Carpenter’s Six Months at the White House with Abraham Lincoln, the Story of a Picture. In this memoir Carpenter relates the backstory behind his painting, The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation Before the Cabinet. Carpenter arranged for Berger to photograph Lincoln as reference for the painting—three sittings in February and April 1864.

The Lincoln and Tad portrait was one of seven photographs made by Berger on February 9.

Getting out from under Brady’s shadow proved a difficult, if not impossible, task for Berger. When his portrait of Lincoln and Tad appeared on the cover of the May 5, 1865, edition of Harper’s Weekly, Brady received the attribution. The magazine’s editors, to their credit, published a correction on the back pages of its next issue.

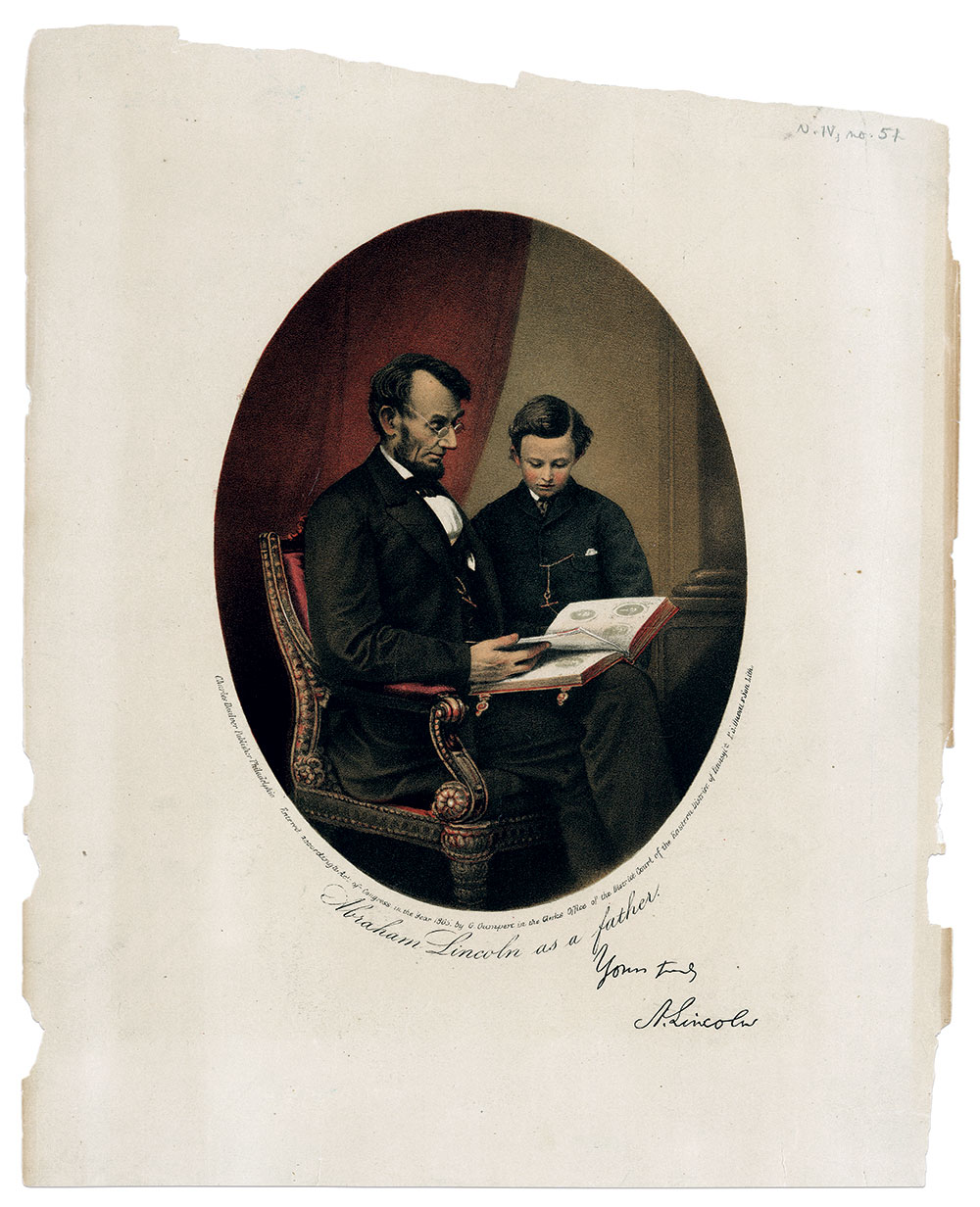

The Harper’s Weekly engraving bears striking similarities to a retouched version of the Lincoln and Tad portrait published by Berger in the carte de visite format with a black mourning border on its cardstock mount. Berger copyrighted it under his own name and Brooklyn studio in 1865. Both have been modified in several ways. The addition of a background suggests a room inside the White House. The photograph album pages were converted to book pages, which, along with the album clasps, suggest father and son studied the Bible. Fabric and fringe may have been added to the chair to distinguish it from a furnishing in Brady’s studio.

Berger’s popular photograph proved irresistible to competitors who took advantage of weak copyright laws, and pirated versions for mass production to a public eager to insert this likeness of their fallen leader into their own albums. Representative examples of these variants inspired by the original Lincoln and Tad photograph are pictured here.

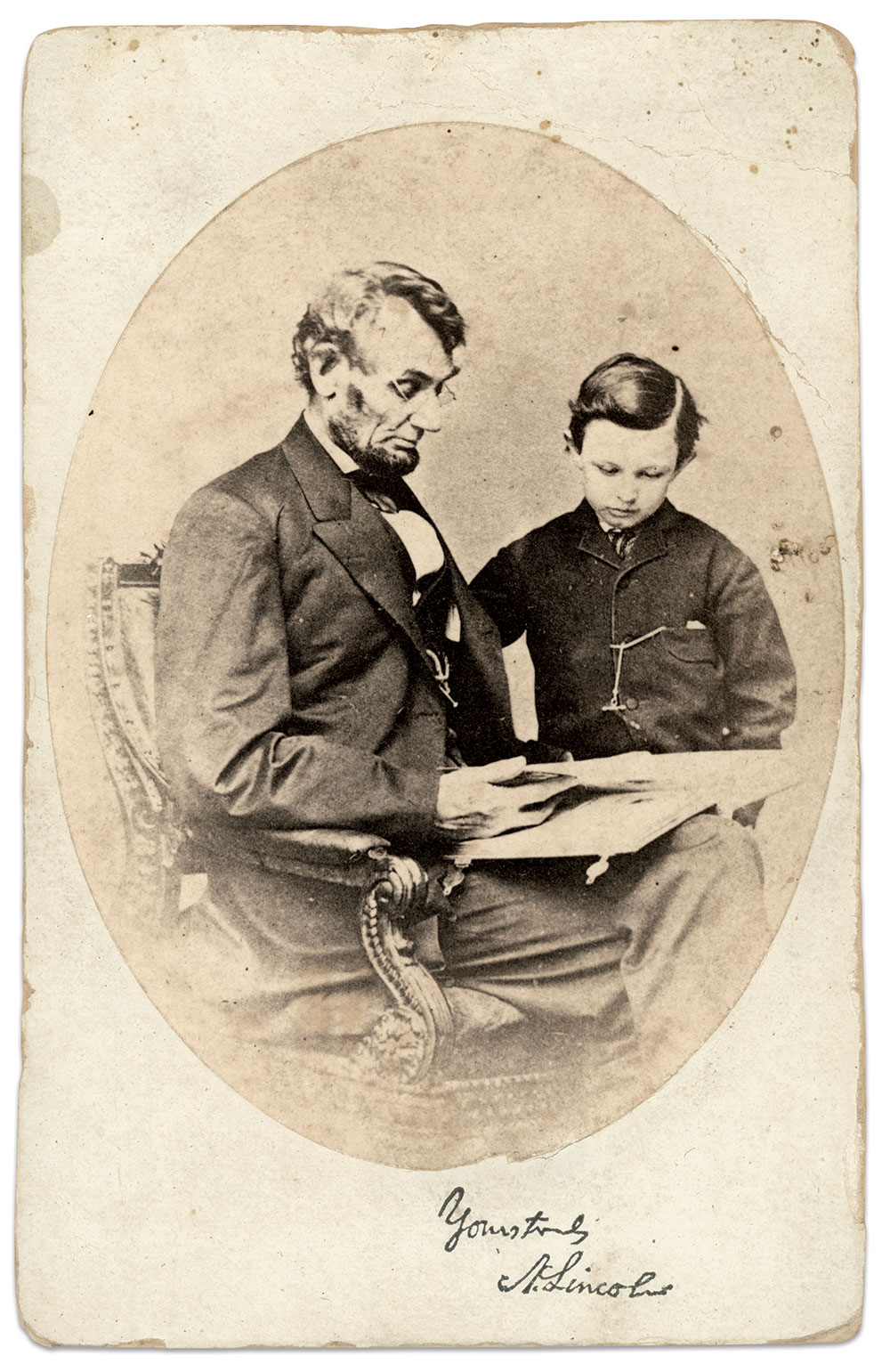

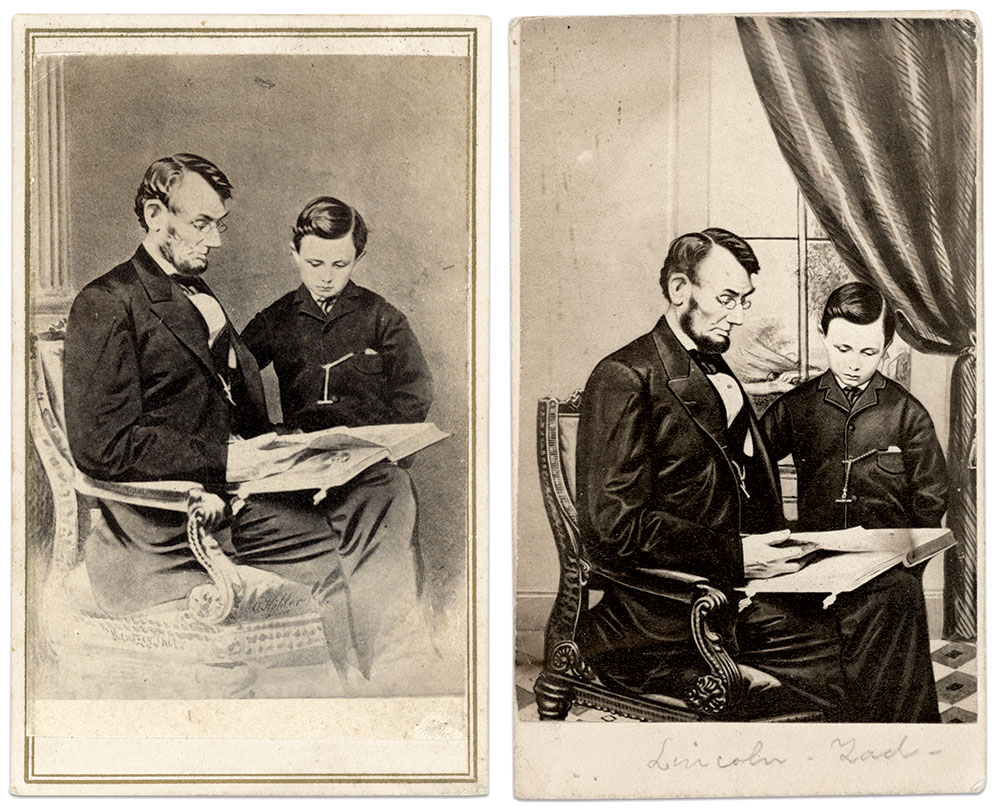

Studio chair with album pages

Berger’s original portrait with the studded studio chair and unaltered album pages enjoyed wide circulation, as evidenced by the number of surviving images compared to other variants.

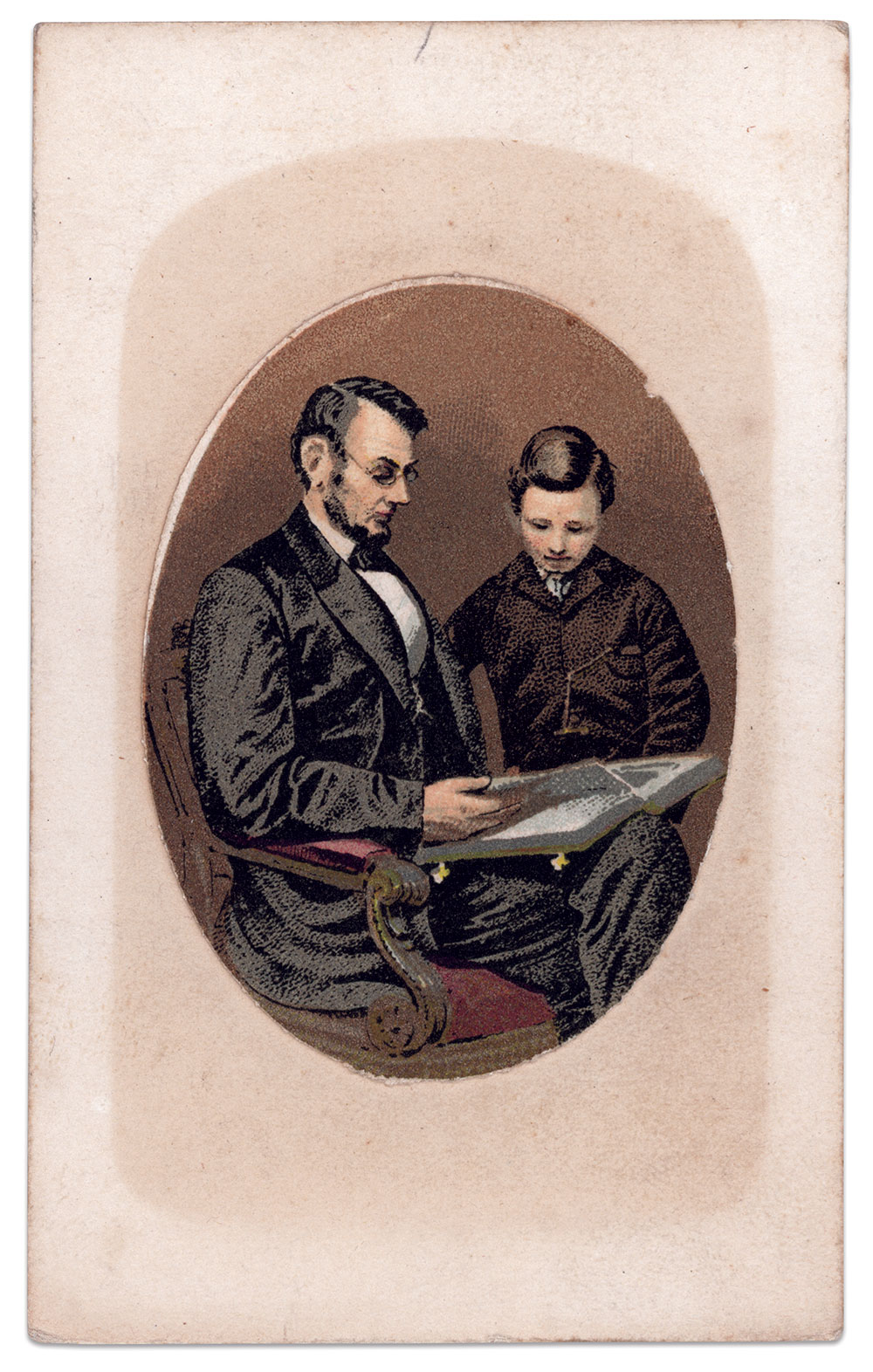

Studio chair with Bible pages

This lithograph with the original studio chair pictures Lincoln turning pages that appear to have columns of text, suggesting the President is imparting lessons from the Bible to his son.

Fringed chair with Bible pages

Berger published a version of Lincoln and Tad retouched to add fringes to the chair and transform the album to a Bible. An advertisement on the back of the mount pairs this image with the likeness of the soldier who shot and killed John Wilkes Booth, Sgt. Thomas H. “Boston” Corbett of the 16th New York Cavalry.

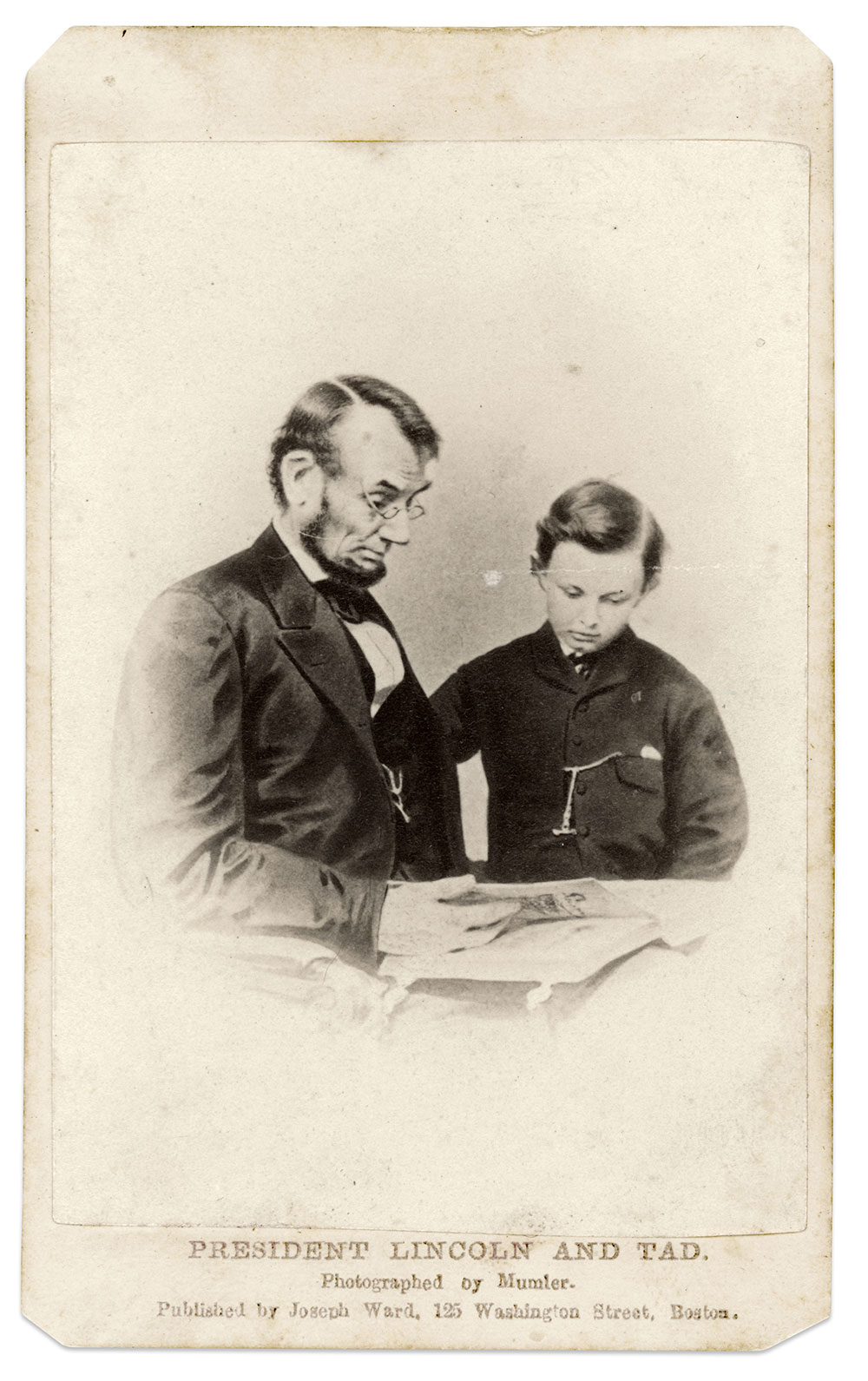

Illustrated page with a subtle spirit?

In this vignetted view, the underside of the single page in Lincoln’s hand appears modified with a human figure with an outstretched arm. The figure may be a creation of spirit photographer William H. Mumler, whose imprint appears at the bottom of the mount.

Environmental backgrounds

The addition of backgrounds place Lincoln and Tad in different environments. In one, a column behind Lincoln’s chair reinforces a studio setting. In the other, a draped window suggests a home setting.

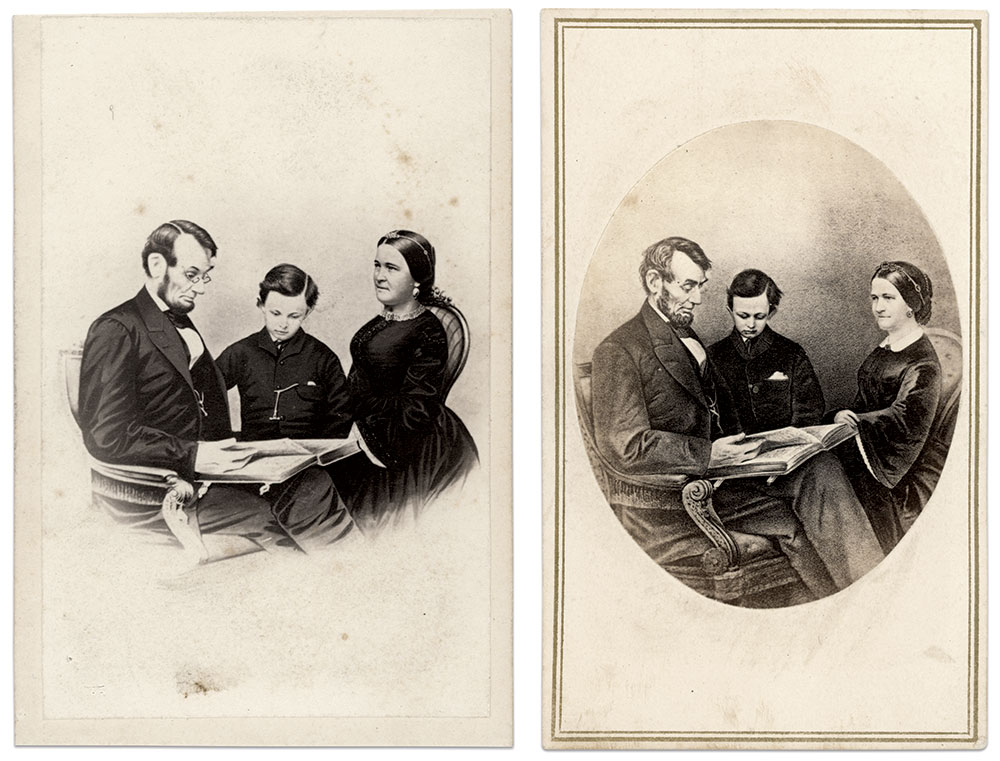

Mary joins her husband and son

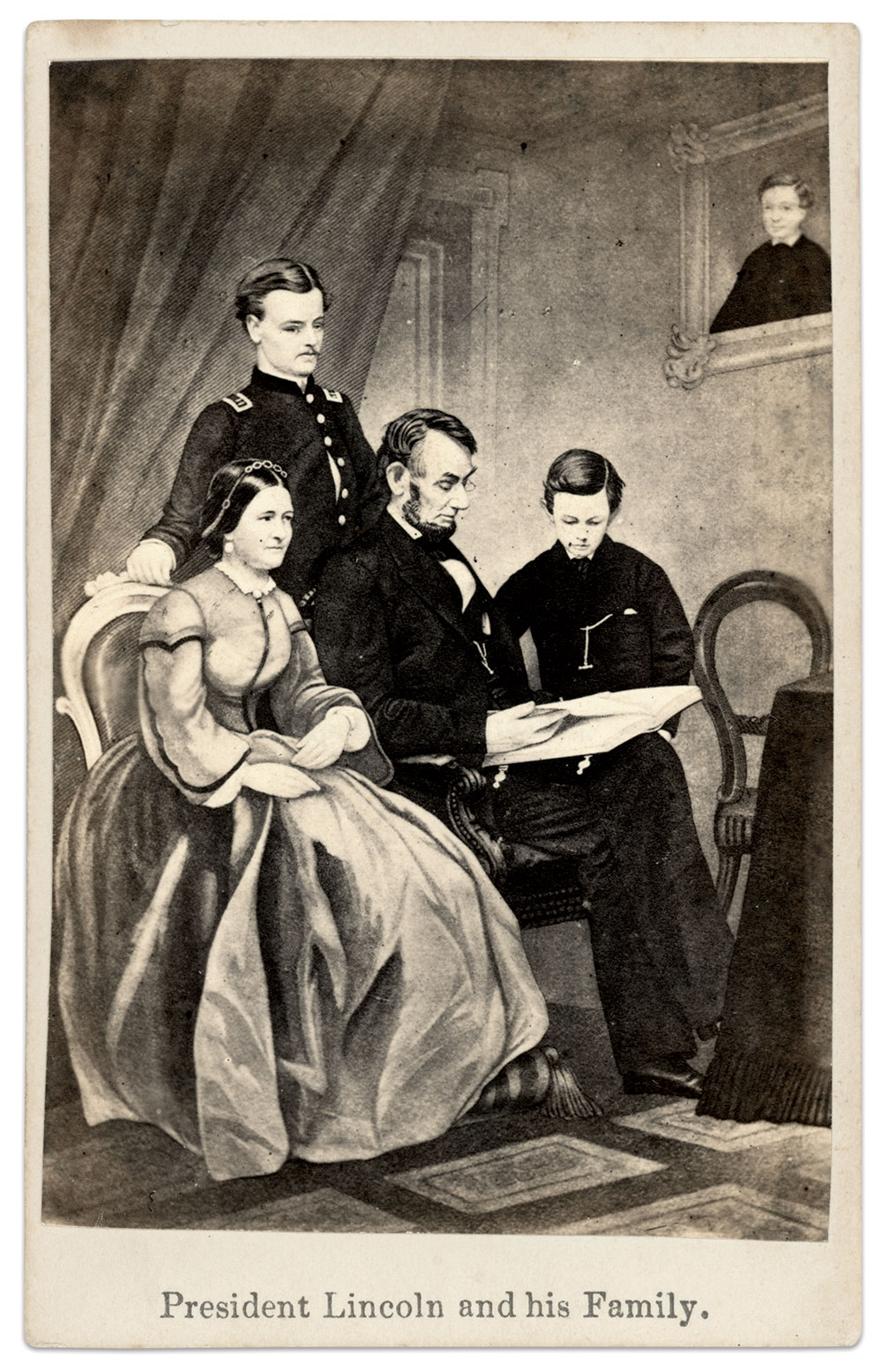

No primary source exists of the Mary Todd and Abraham Lincoln posing together for a photograph. Their eldest son, Robert, confirmed this to Lincoln scholar and collector Frederick Hill Meserve. Surviving photographs pictured here are evidence that the public wanted to see the Lincolns together. Thanks to 1860’s Photoshop, Mary appears next to Lincoln and Tad.

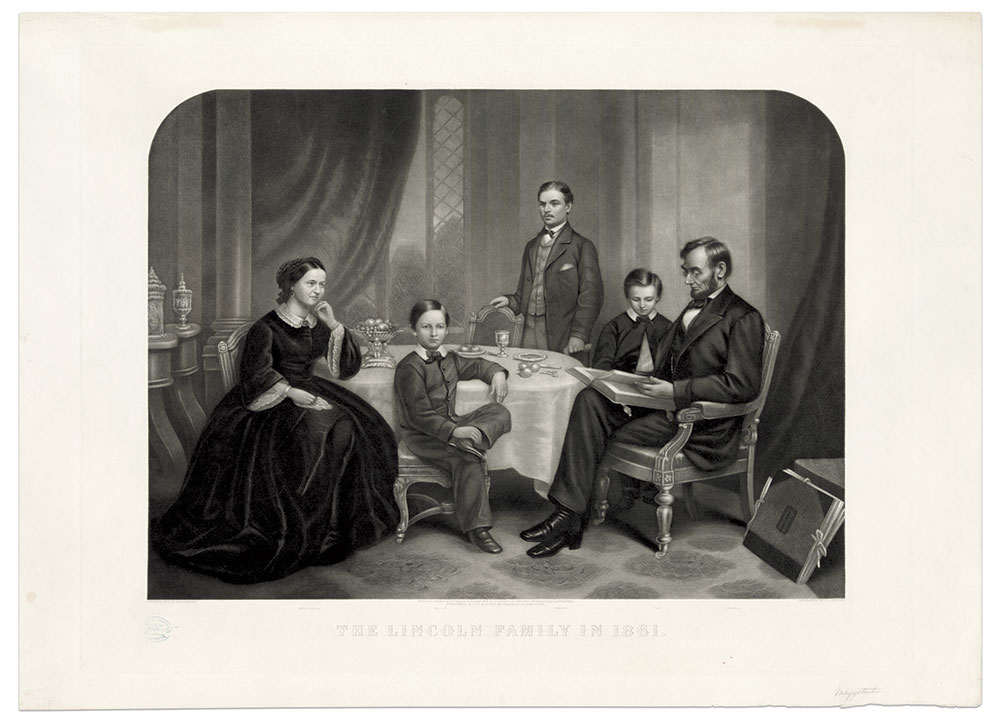

Pictured with the rest of the family

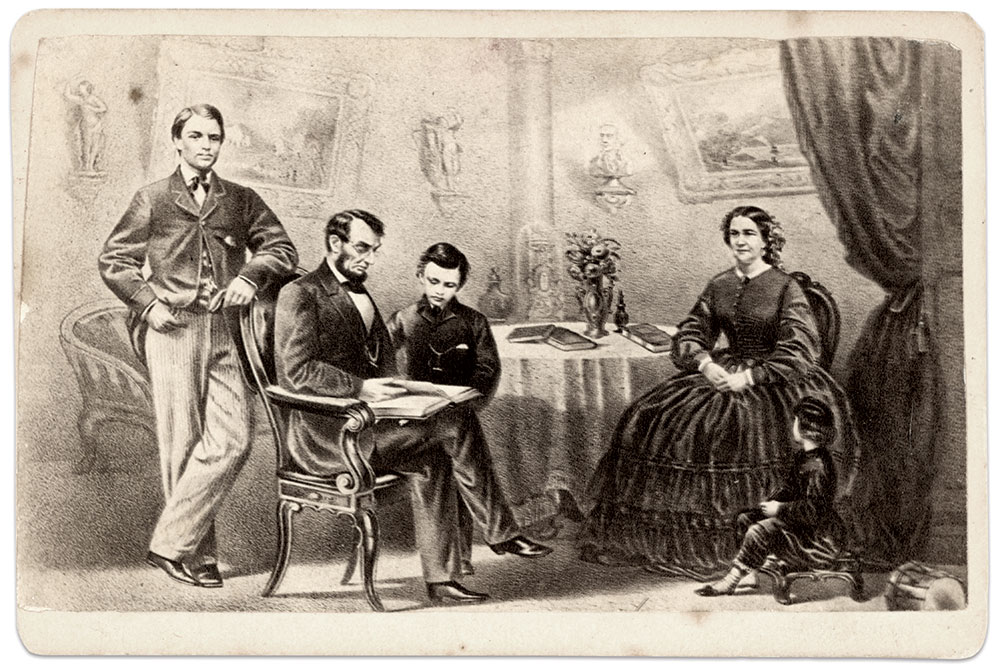

Carpenter’s “The Lincoln Family in 1861” incorporates Berger’s Lincoln and Tad photo into a room presumed inside the White House. Mary sits at the left, glancing towards her husband. Willie, who died in 1862, stares directly at the viewer. Eldest son Robert stands in the background. Other artists adapted Berger’s portrait, likely without consent, for their own family scenes.

New York artist Henry A. Thomas’ drawing angled Tad’s head to make him appear more engaged with the book. Mary sits at the other end of the table. Willie, his face averted in a period convention for portraying dead children, gazes towards his mother.

Philadelphia artist Frederic B. Schell’s family portrait depicts Willie’s likeness in a frame—another convention to portray deceased family members. Schell places Mary close to her husband, and features Robert in the uniform of an army captain, in which capacity he served as a member of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s staff in the waning days of the war.

References: Carpenter, Six Months at the White House with Abraham Lincoln, the Story of a Picture; Heberton, Craig. “February 9, 1864: Lincoln’s Magical Photographic Session with Anthony Berger.” Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg; Harper’s Weekly, May 5 and 12, 1864. abrahamlincolnatgettysburg.wordpress.com/tag/anton-berger/

Chris Nelson is an MI Contributing Editor.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.