By Ronald S. Coddington

A new memorial to honor Mathew Brady is scheduled to be unveiled this year near his burial site at Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Years in the making, it recognizes his contributions as a pioneer photographer, technical innovator, entrepreneur, photo team leader and recorder of American history.

The Mathew Brady/Levin Handy Memorial at Historic Congressional Cemetery is the culmination of the vision of Larry J. West, a collector of 19th century photography focused on African American daguerreotypists, photographs connected to the abolition of slavery and the Underground Railroad, and photographic jewelry. Last year, the Smithsonian Institution’s American Art Museum acquired 286 of these objects. The L.J. West Photograph Collection represents the largest single concentration of daguerreotypes by early Black photographers James P. Ball, Glenalvin Goodridge and Augustus Washington.

West’s vision for the memorial traces back to a visit to see Brady’s gravesite some years ago. Brady died in 1896, and his loss ended a celebrated six-decade career during which he rose to become a leading light in the nascent photography industry and the father of photojournalism. His fortunes declined after the war, and he left a modest estate to his widow, Julia Handy Brady.

Levin C. Handy, Brady’s nephew, photographer, and business associate, arranged to have the remains interred in the Handy family plot in Congressional Cemetery. Established in 1807, the 35-acre grounds are a resting place to nearly 70,000 individuals, including notable political and military figures, and other prominent citizens.

During his visit, West noticed that the Handy plot, located on a hill, had open space around it. He inquired with cemetery staff to learn why, and much to his surprise and delight, learned that two adjacent plots had never been sold. West immediately purchased the interment rights to them with a memorial in mind.

West determined that the new memorial would be interactive, educational, photographically intensive and state of the art. Also, that the materials and construction above and below ground last a minimum of 200-250 years—and able to survive earthquakes, such as the one that shook the city in 2011 and damaged the Washington Monument and other structures.

West reached out to Daguerreian scholar Grant Romer, who helped conceptualize the design, and engaged consultants to advise on the structure and the on-site visitor experience.

Their research revealed that four other photographers are buried near Brady, the last passing in 2010. West induced the Congressional Cemetery leadership to name this section Photography Hill in their honor.

The memorial is constructed on a rectangular platform about 9-by-11 feet. The space is dominated by a columbarium and three figures.

The columbarium

The largest feature is a granite columbarium standing nearly 8 feet tall, 8 feet long and 2 feet wide. On one side are two interpretive bronze plaques below the words “The Mathew Brady Memorial.” The plaques detail Brady’s life and contributions in words, including several of his most memorable quotes, such as, “The camera is the eye of history.”

On the other side of the columbarium, facing the two other life-size bronzes, and a ceramic image of Brady, is a wall of 83 fired porcelain, artisanal Italian ceramic images, almost all showcasing iconic photographs taken by Brady or by his teams of photographers, and other practitioners of the craft.

West chose ceramics over etched black granite, a popular modern technique to display the photographs, noting, “The real beauty of basing a memorial on photography is the ability to show actual, detailed images of the people involved.” The ceramics possess superior brightness and clarity, and with their high tech coating will not fade in direct sunlight or severe weather.

The wall of images is arranged in five groupings:

- The Brady family, including his nephew Levin, who began working in Brady’s studio as a boy, took care of the Bradys during their final years, and went on to become the official photographer of the construction of the Library of Congress.

- President Abraham Lincoln, Mary Todd Lincoln, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, and other notable Civil War figures.

- Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth and other African American leaders connected to the Underground Railroad, Black art and culture, and U.S. Colored Troops.

- Prominent individuals in arts and entertainment include John Philip Sousa, Edward Allen Poe, Charles Dickens, and Tom Thumb.

- American history as depicted by Brady images on U.S. postage stamps.

Between the walls in the columbarium are cremation chambers for eight photo historians, among them West and Romer, Civil War collector Dr. Robert Drapkin, and their spouses.

The figures

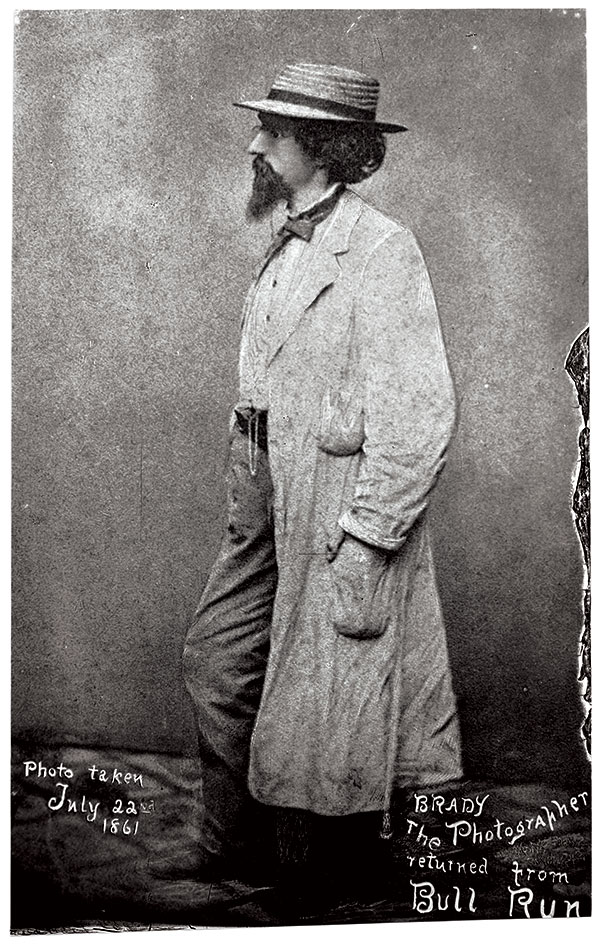

The central figure on the platform is Brady. He is represented in a 5-foot 6-inch full-sized ceramic porcelain set within a granite backer. The image is taken from a photograph of him in July 1861, after he trekked to Manassas, Va., to photograph the battlefield of Bull Run, the war’s first large-scale battle that ended with Union troops and naïve picnic-goers skedaddling back to the safety of Washington, D.C. The rebel victory dispelled any notion that the war would be short and decisive.

Brady wears a straw hat and long smock coat, inside which concealed a sword reportedly given to him to defend himself after being knocked to the ground and suffering the loss of a camera. Next to the Brady ceramic rests a three-dimensional bronze sculpture of his camera.

The other two figures are life-size bronze statues of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. The figures are modeled after Brady portraits. Each man holds a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln holds the document open to reveal its contents, and it is readable to visitors. Douglass holds the document rolled up. His wife, Anna Murray Douglass, is pictured across from him on a ceramic image, mounted on the opposite side of the granite backer to which is attached Brady’s ceramic. A bronze plaque below her portrait details her contributions as an abolitionist and a stationmaster on the Underground Railroad.

Interactive space

The configured space encourages visitors to interact with the memorial. West notes that a person can pose for a photograph between the statues of Lincoln and Douglass or stand with Brady and his camera. West also observes that the memorial is designed to allow docents and others to stand and speak in the middle of the space, or at one end of the platform without obstructing the overall view of the site.

A brochure, Photography Hill at Congressional, will be available on site and online.

The memorial is adjacent to the Handy plot with its original headstones for Brady, wife Julia, and the Handy family intact and undisturbed. Also inside the original plot is a memorial stone erected by a group of Civil War enthusiasts from Warren, Ohio, who visited the site in 1988 and noticed an incorrect death date of 1895 on Brady’s original grave marker. As it turns out, a streetcar had struck Brady in New York City, and he gained admission to a hospital in December 1895. He died on Jan. 15, 1896. The Ohioans corrected the death date on the new marker, and paid tribute to Brady as a “Renowned Photographer of the Civil War.”

West observes that the scope of the new memorial recognizes Brady’s entire career and legacy, saying, “I understood his important role in recording and using war images to become a father of photo-journalism. But I wanted to assure that thousands of D.C. and web visitors came to know him as I do—via a photo-historian plus businessman perspective.”

The platform is in place. West plans on installing the rest of the memorial early this summer.

West mused one day on the site that, “I discovered that standing at the edge of the platform, with the sun at my back, looking down at Brady’s headstone, my shadow falls across his grave just as his life-size porcelain and bronze camera shadow will probably do after construction. Perfect.”

West will measure the new memorial’s success by increasing visitor traffic and raising the profile of Congressional Cemetery as a destination for events and activities, telling stories about African-American history, and raising awareness of Mathew Brady and Levin Handy.

West shared that he also sees the memorial as “a super special place where our group of photo-historians can be buried close to Mathew and Levin in a national historic site in the nation’s capital.”

He adds, “and maybe get to run rampant at nighttime with Mathew’s ghost.”

Call to action: Plans for a dedication ceremony are in progress. To get your invitation and more information about the memorial, contact BradyMemorialat200@gmail.com.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.

1 thought on ““The Camera Is the Eye of History”: A new memorial in Washington, D.C., honors Mathew Brady”

Comments are closed.