By Paul Russinoff

A column of dilapidated wagons and carriages drawn by broken-down horses creaked along a neglected Mississippi road one summer’s day in 1863. The thoroughfare stretched for some 20 miles, from Port Gibson to the village of Rodney on the banks of the Mississippi River—towns and territory controlled by federal forces.

The vehicles carried 50 Confederate prisoners, under guard by a battalion of Union soldiers.

The captives were no ordinary prisoners, but well-to-do belles of Port Gibson’s aristocratic families. They were on the way to Vicksburg, to be held as hostages until the Confederates released a group of abducted New England abolitionist schoolteachers forced to cook and clean for the rebel army.

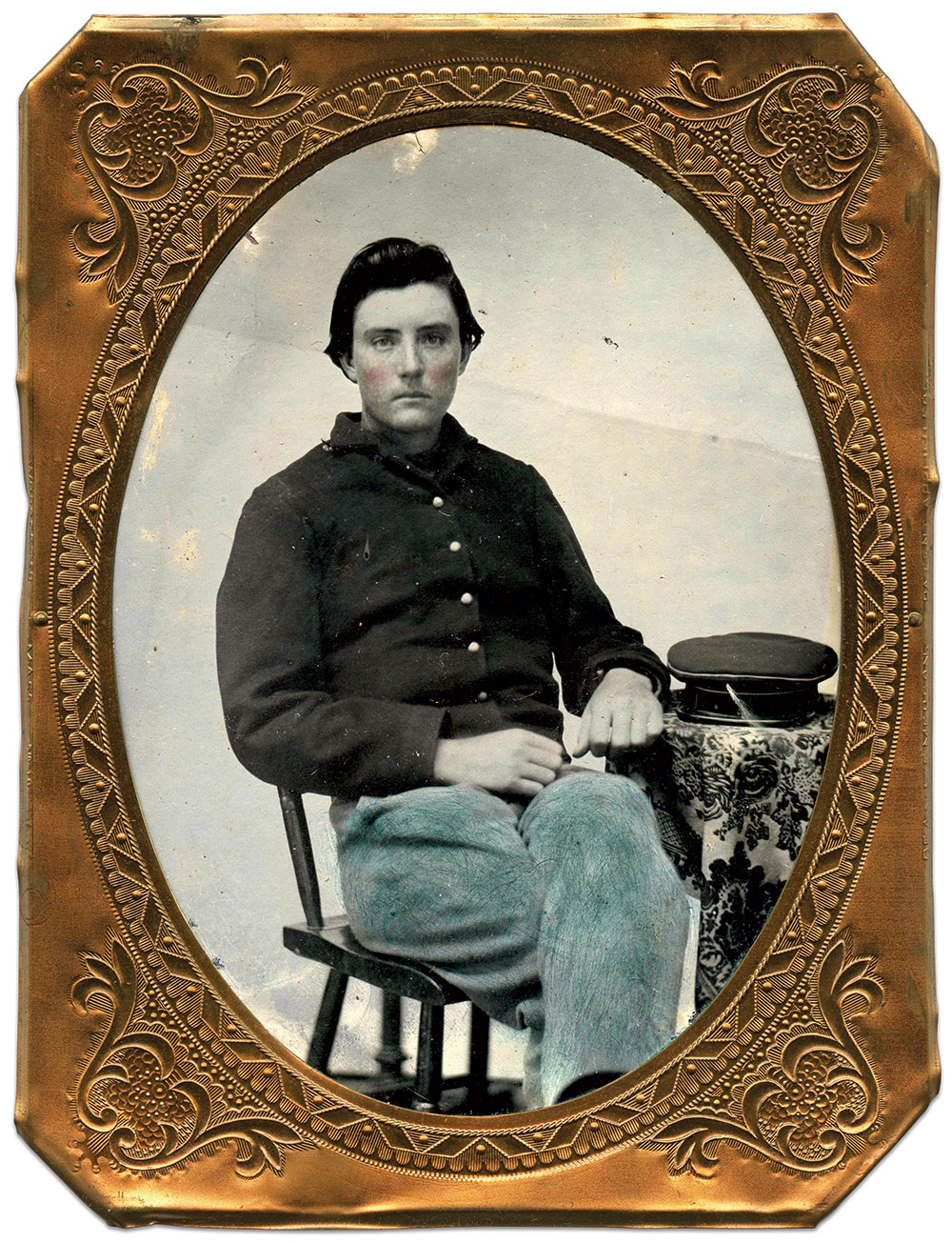

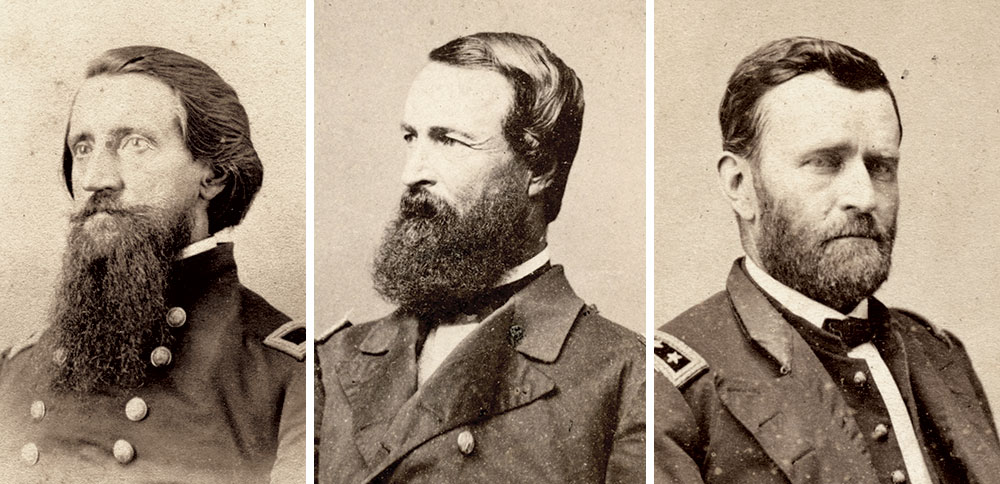

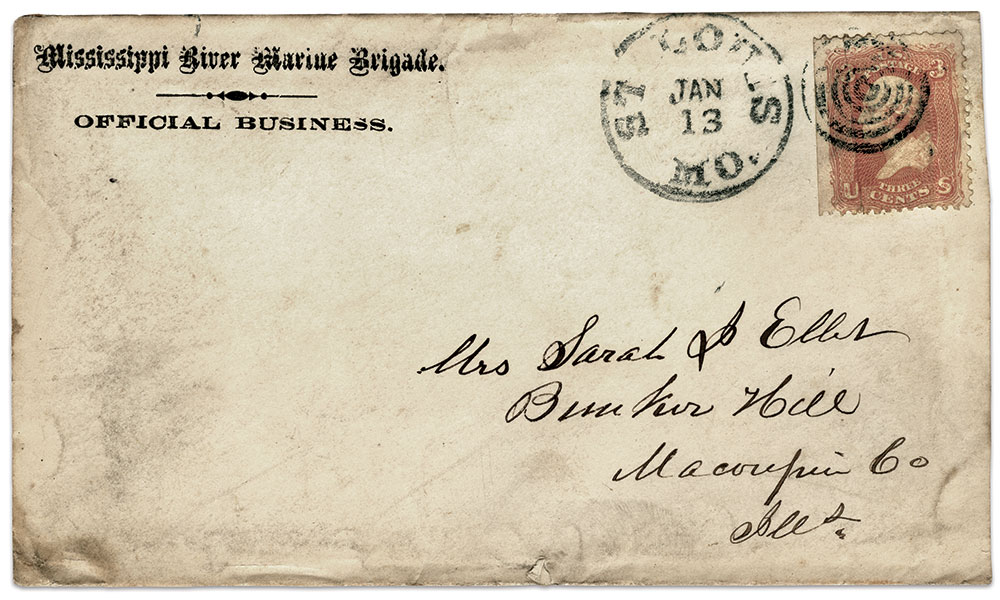

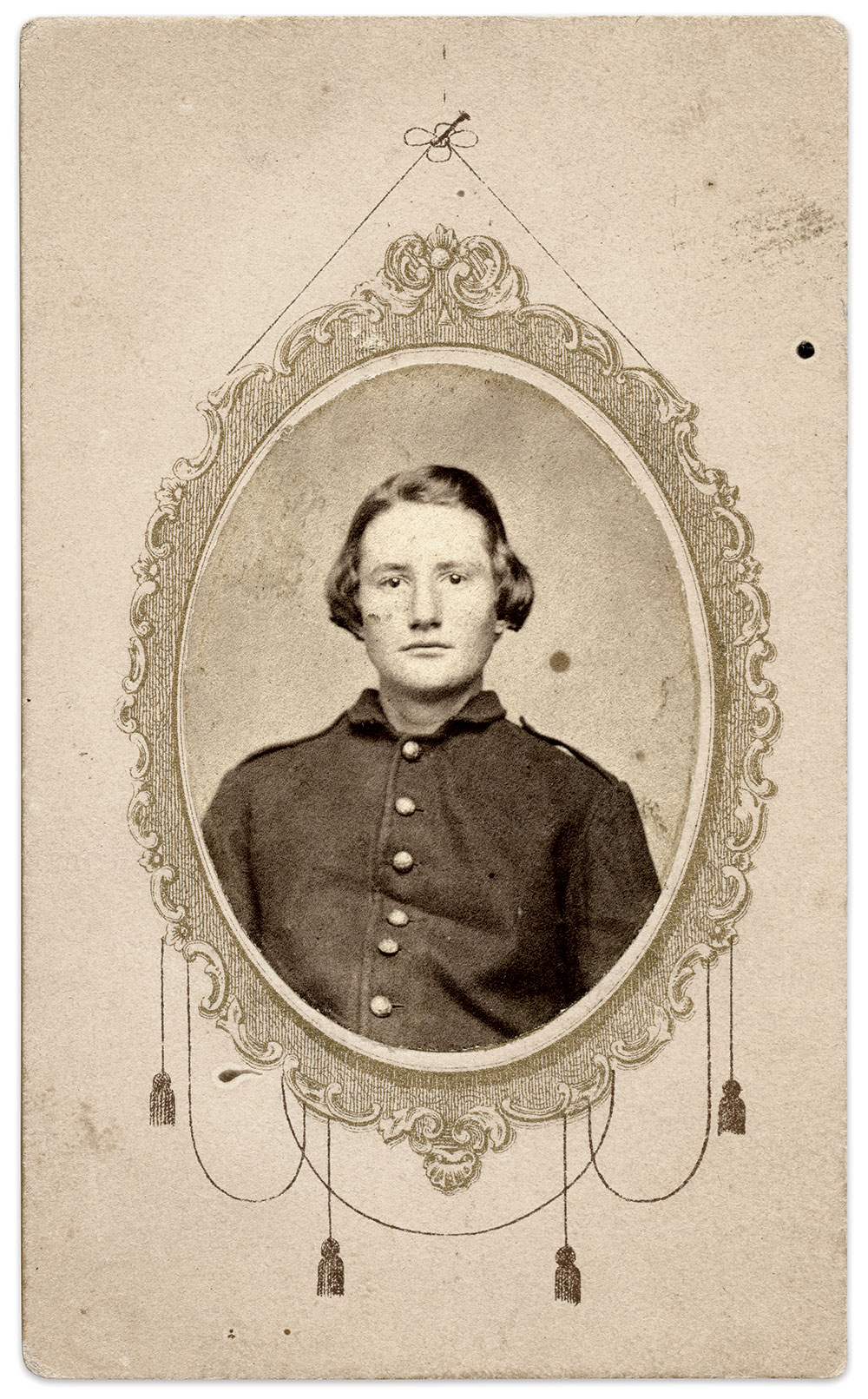

The Union soldiers who guarded the young women were no ordinary fighting men. They belonged to an independent amphibious force organized in late 1862—the Mississippi Marine Brigade. One of its members pictured here displays the Brigade’s distinctive circular-crowned cap. He is William Riley Houts, 19, an ideal candidate for this unconventional unit of warriors. Houts started his war service in September 1862 when he mustered into Company K of the 123rd Illinois Infantry. The following month, only days after it left Illinois, the regiment had its first experience in a major battle at Perryville, Ky. While fighting on the Union left as part of Brig. Gen. William R. Terrill’s Division, a rebel shell exploded over Company K, killing three soldiers. One of the shell fragments lodged in Pvt. Houts’ lower back. A surgeon removed it that day, and Houts saved the iron chunk as a souvenir.

While not life-threatening, the wound affected his motion. Still, the plucky Houts remained with his command for a month, riding in an ambulance and performing light duty. By late November, the effects of the wound, as well as a case of mumps and diarrhea, landed Houts in hospitals at two locations in Kentucky, Woodville and Louisville.

It was likely at one of these places that Houts became aware of recruiting handbills, circulated in military hospitals from Cleveland to Nashville, which read, “Soldiering made easy! No hard marching! No carrying knapsacks! There will be but very little marching for any of the troops. They will be provided on the Boats with good cooks and bedding.”

The handbills were written to attract recruits for the Mississippi Marine Brigade; a strike force rooted in another novel organization, the U.S. Ram Fleet.

Dreams of killer rams

Back in the spring of 1862, months before Houts joined the 123rd, the origins of the Brigade took form in an independent fleet of steam rams. This fleet was the brainchild of civil engineer and bridge builder Charles Ellet, Jr., whose interest in naval vessels designed to ram and sink enemy ships began well before the war. The concept dated to Greek rowing galleys of antiquity. Ellet drew further inspiration from a contemporary incident. In 1854, the large passenger and mail vessel Arctic steamed from New York City to Liverpool, when it collided with the small French steamer Vesta off the Newfoundland coast. The Artic sunk with the loss of more than three-quarters of its 400 passengers and crew. The badly damaged Vesta made harbor at St. Johns.

Ellet became convinced that fast-moving steamboats with sharp, iron-reinforced bows could sink formidable ironclad vessels, and pitched the idea to the Russians during the Crimean War. They declined. So did the British, and the Americans too.

By 1861, circumstances had changed considerably. Steam engines were faster and better. The transformation of wood to iron warships became a mandate when the U.S. Congress recommended the construction of such vessels for the Navy.

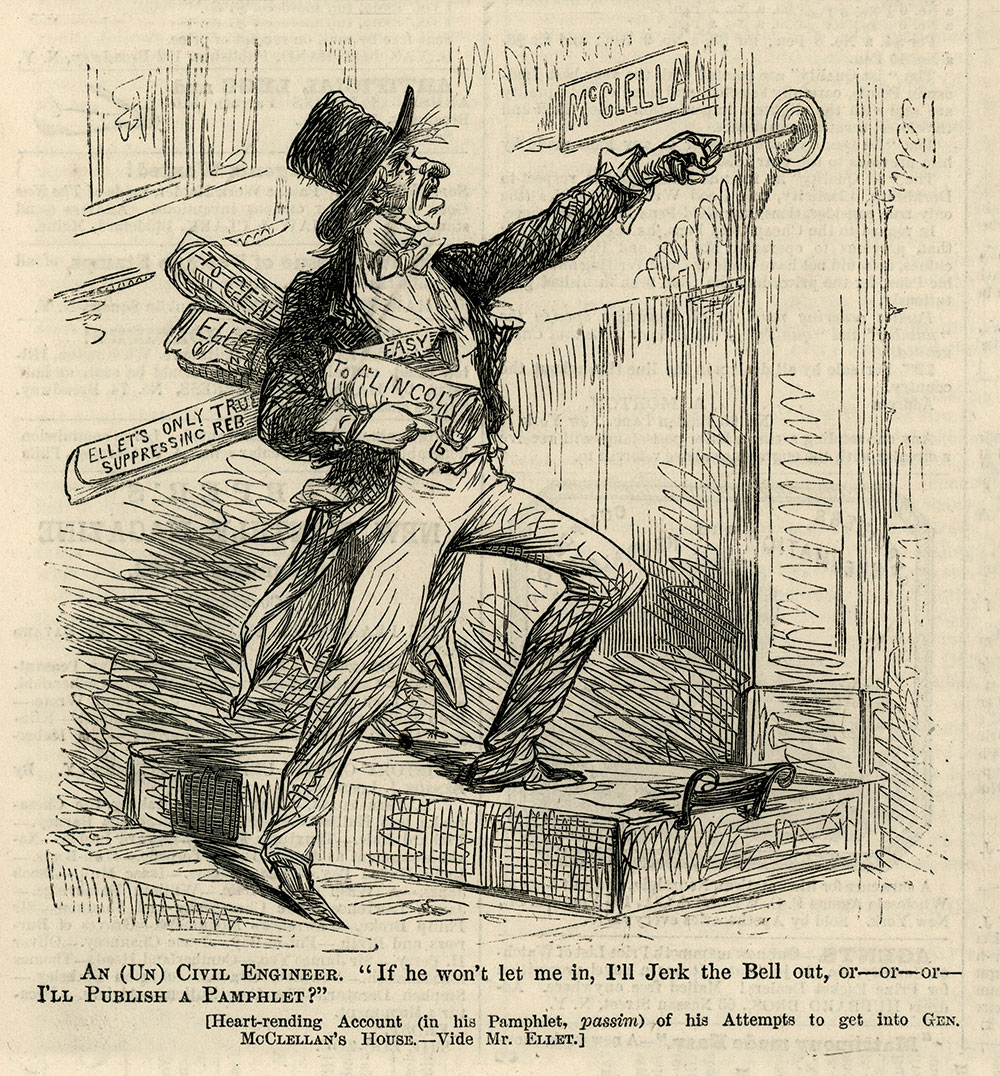

Ellet lobbied the government to sell his ram concept, but success continued to elude him despite the more favorable climate. He needed the right timing, which came in March 1862 after the Monitor and Virginia fought to a draw at Hampton Roads, Va., and ushered in the era of iron fighting ships. Rumors of ram development by the Confederates fueled the federal government’s desire to establish a similar program.

A connection high up in the government— Edwin M. Stanton, President Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of War—made the dream a reality. Stanton, a peacetime attorney, had firsthand knowledge of Ellet’s engineering accomplishments during his work as counsel in a lawsuit involving one of Ellet’s greatest projects, the Wheeling Suspension Bridge spanning the Ohio River in Virginia.

Stanton embraced Ellet’s plan for a fleet of rams despite his lack of military experience—a deficiency that Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles could not get past. In fact, Stanton worked outside traditional military channels, the result of which was Ellet’s force being an independent command that drifted in and out of coordination with the navy and army. One writer described the force as “Stanton’s Private Navy.”

On March 27, Stanton dispatched Ellet to Pittsburgh to “provide steam rams for defense against iron clad vessels on the Western waters.” A colonel’s commission followed, along with detailed instructions that gave Ellet a great deal of authority and resources to purchase a number of vessels, modify them accordingly, and recruit crews.

Stanton also granted Ellet’s request that his younger brother, Alfred Washington Ellet, then a captain of a company in the 59th Illinois Infantry, become second in command. He received a promotion to lieutenant colonel and the transfer of his infantry company to the fleet.

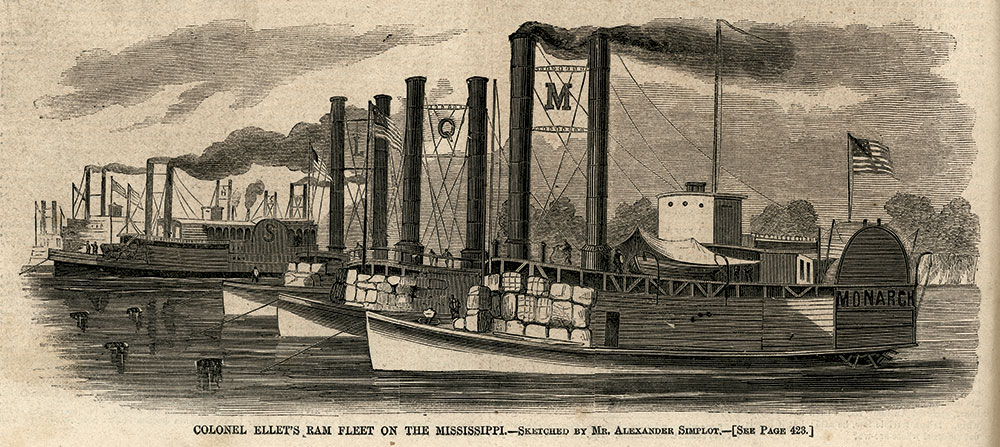

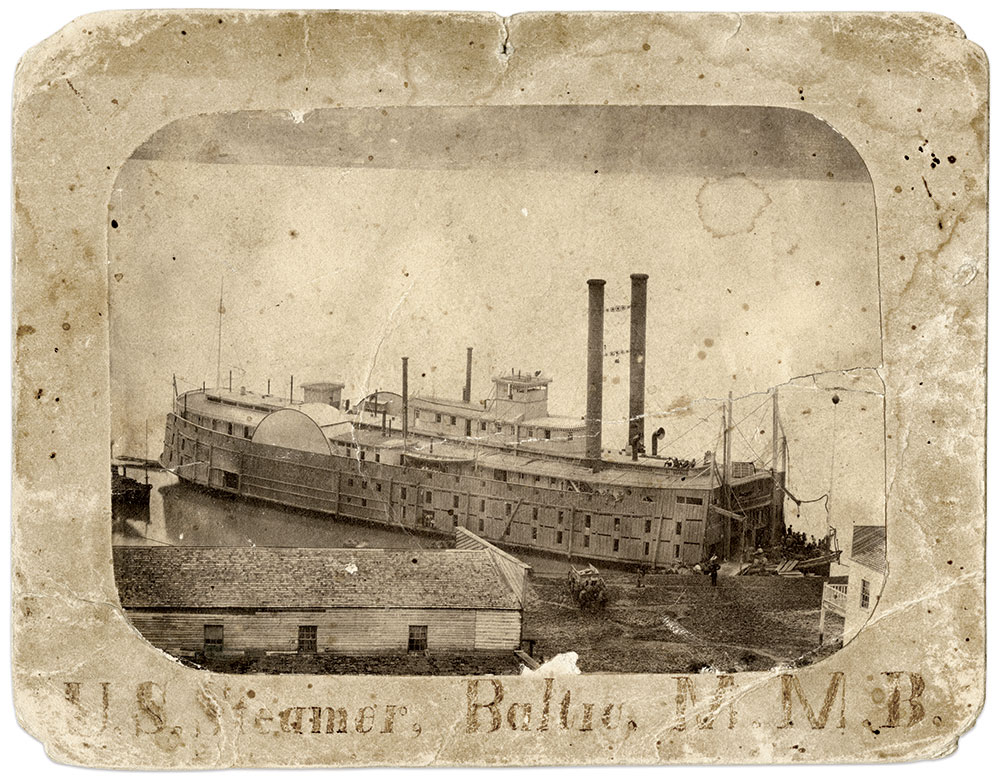

The fleet quickly ramped up. Colonel Ellet put his technical smarts and organizational abilities to work and converted nine civilian steamboats into a fleet of military rams manned by capable crews and troops. By May 1862, Ellet’s armada steamed south along the Mississippi. It included the Dick Fulton, Lancaster, Lioness, Mingo, Monarch, the flagship Queen of the West, Samson, Switzerland and T. D. Horner.

Meanwhile, plans were laid for joint army and navy operations to capture Memphis by way of the Mississippi. Stanton informed Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck and the Navy that Ellet’s ram fleet would participate. Ellet initiated a meeting with his Navy counterpart, Capt. Charles H. Davis, which reportedly proved more cordial than cooperative.

Still, the independent commands managed to pull together when they steamed into range of the defenses of Memphis and faced off against nine enemy rams on June 6, 1862. Davis’ five slower-moving gunboats drew the initial artillery fire as Ellet’s rams swiftly sped through the formation and engaged the rebel rams, sinking one and capturing two. Davis’ gunboats followed up by taking three more of the Confederates vessels, with two captured and the third destroyed.

As the surviving Confederate rams fell back and the Navy attended to the captured vessels, a contingent of officers and crew from the Marine Brigade jumped into a rowboat and made haste for the city. They landed on a wharf, accepted the surrender of Memphis, and hoisted the Stars and Stripes from the top of the post office.

Two days later, Ellet received a telegram from Stanton, congratulating him on his glorious victory. Captain Davis received a similar telegram from his superior, Secretary Welles.

Ellet did not enjoy the glory for long. A knee wound he had received during the fight while aboard the Queen of the West became infected. He succumbed to the injury on June 18, just as the vessel carrying him reached the Union base of operations at Cairo, Ill. Command of the Brigade passed to his brother, Alfred.

Memphis proved the fleet’s greatest military achievement. The rams spent the next few months in cooperation with Rear Adm. David Farragut’s fleet in the vicinity of New Orleans, and Capt. Davis in a failed attempt to take out the Confederate ironclad ram Arkansas.

Birth of the Marine Brigade

In a flurry of activity in Washington during the autumn of 1862, Stanton transferred all Army gunboats from the War Department to the Navy, an organizational move that brought all the vessels of the Mississippi Squadron under a single unified command. Davis was out, promoted to a new post in the Navy Department. Acting Rear Adm. David Dixon Porter replaced him.

Stanton issued another order for Ellet to report to Porter. Details about how this change affected the independence of the ram fleet were an open question, and Ellet wanted answers. He received some clarification soon after in a meeting with Porter. During the conversation, Ellet pointed out the damage Confederate guerrillas were doing to Union military shipping on the Mississippi. Moreover, that a brigade of Marine troops could be effectively deployed against them. Porter agreed and indicated that Ellet should be in charge.

Ellet received more good news in a letter from Stanton, who stated that command of the rams would remain with Ellet, and called him to Washington, D.C., to confer. There, Ellet presented his detailed plan of a Marine strike force able to quickly discharge from a steamboat. The Marines, he suggested, would be ideally suited to intercept and defeat irregular troops and guerrillas operating against the Union Navy on the Mississippi and her tributaries. Ellet proposed organizing his men into a regiment of infantry, a cavalry battalion and four artillery batteries—and the existing ram fleet.

Stanton wholeheartedly approved, and further empowered Ellet with a brigadier’s star.

Lincoln, predictably open to experimentation for potential future advantage, supported Stanton.

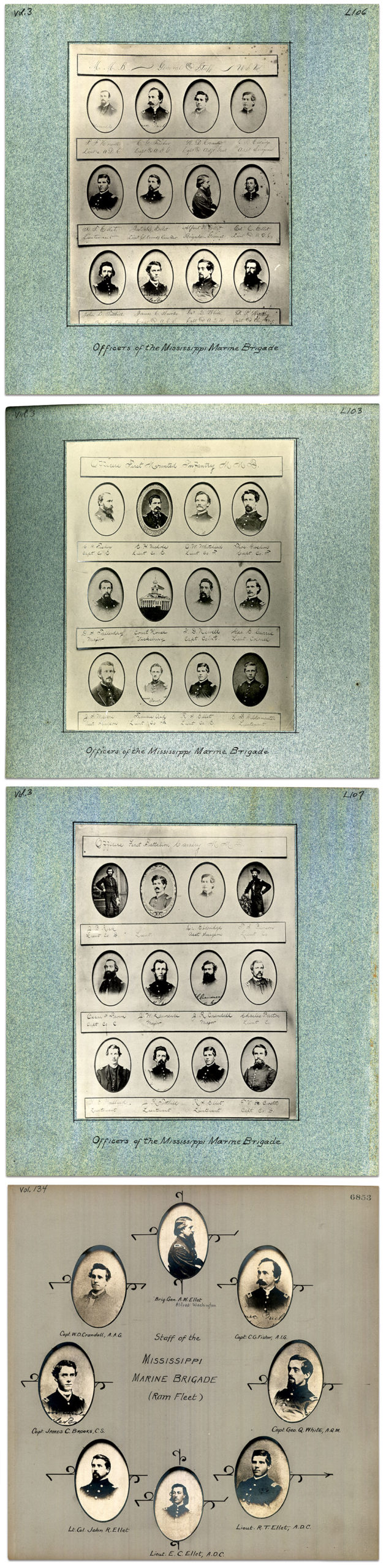

Ellet, following in the footsteps of his late brother, promoted his 19-year-old nephew, Charles Rivers Ellet, from medical cadet to colonel, and detailed the young officer to command of the ram fleet under Porter’s direction. Ellet left his nephew and went to St. Louis, where he spent the remainder of 1862 and early 1863 building the amphibious strike force.

Ellet assigned the task of building a second fleet of seven landing crafts for the Marines to his quartermaster, Capt. James Brooks. These vessels were outfitted with oak planks dotted with musket loopholes, iron-plated pilot houses, cranes that lowered a generous gangplank to deploy men, horses and equipment, and hoses capable of spraying scalding jets of boiler water on enemies that attempted to board.

The intent and design of these vessels are reminiscent of amphibious crafts developed in the next century for beach landings during the world wars and other conflicts.

Ellet delegated recruiting efforts to Capt. William D. Crandall. He can be fairly credited with bringing Houts, still recuperating from his Perryville wound, into the Brigade.

Houts, one of Crandall’s early recruits, signed up on Jan. 14, 1863, and joined Company A, commanded by Capt. Isaac D. Newell. Houts and his fellow Marines received shell jackets with brass shoulder scales or cloth epaulettes and Germanic wheel-hats with leather visors trimmed with green bands and white facings.

Despite a host of attractive inducements, recruitments fell short: 527 infantrymen, 140 artillerymen and 368 cavalrymen. No provisions were made for a chaplain. On the plus side, these men were, like Houts, military veterans. They received extensive basic training uniquely geared to integrate the three military branches represented. Lieutenant Col. George Currie, in charge of daily operations, supervised exercises at Benton Barracks in St. Louis.

In mid-March 1863, the Brigade boarded the new amphibious crafts and steamed south, but problems began almost immediately. On the journey down river, short rations were not living up to recruiting claims. In an apparently coordinated act of insubordination involving four of the vessels, the Marines rioted, upsetting tables and benches in the dining halls of the boats, destroying officers’ quarters, and attacking one officer.

Cattle boats, burning buildings, and the ire of U.S. Grant

On April 26, 1863, at a place where the Duck River empties into the Tennessee, elements of the 6th Texas Cavalry watched and waited for an opportunity to strike enemy targets. When Ellet’s Marines steamed into range, the rebel troopers opened fire with four field cannon and raked three of the vessels with iron. The Texans looked on with evident pleasure at the effects of their handiwork. Their satisfaction turned to shock when the supposed “cattle boats” returned the compliment and fired back. Then, the Union crews pulled the vessels up to the riverbank, lowered the drawbridges and released charging blue knights.

One of the Confederate veterans later recalled it was “the worst his command was ever sold out.” The Marines broke off their pursuit after a 12-mile chase. They returned to their boats, but not before pillaging local farms and a smokehouse. The day’s casualty list included two dead Marines and another wounded, and nine Confederates killed.

Another incident about a month later started under similar circumstances. The Marines were on the way to Vicksburg when their trailing supply vessels came under guerrilla fire near Austin, Miss. Ellet landed 200 cavalry and infantry in the face of surprised villagers. The Union cavalrymen mounted up and dashed off after the enemy—about 800 Arkansas and Mississippi partisan troops armed with artillery. After an 8-mile pursuit, the federals caught up to the Confederates and fought them for two hours until elements of the Marine infantry arrived and forced the enemy to retreat. The Brigade suffered two dead and 19 wounded in the action.

Company A, including Houts, remained behind to guard the town. When Ellet and the rest of the men returned, the enraged general ordered the town burned. The task fell to Houts and his comrades. They torched the village and a nearby academy, despite an appeal by local townswomen to Ellet. After the deed was done, Lt. Col. Currie expressed his mortification. Houts’ company commander, Capt. Newell, recalled that he complied with a “sad heart” and recalled it was “one of the most unpleasant of all my war experiences.”

Days later, Houts and Company A participated in another unconventional action. On May 30, Ellet’s fleet landed at Snyder’s Bluff, along the Yazoo River several miles north of Vicksburg. Ellet sent Company A off to help secure a supply of fresh water located opposite the Confederate-held city and its bristling defenses. Armed with Spencer rifles supplied by the Navy at Ellet’s request, Company A protected crewmembers and Black laborers as they dug rifle pits behind a levee, and then gathered water for thirsty Marines.

By this time, enemy observers got wind of the activity and soon lobbed shells in their direction. Houts and his pards put their rifles to good work as they harassed Vicksburg’s defenders, who retaliated with a more directed fire on their position. No one was reported injured. The water gathering continued for some days, during which Company A and its Spencers were replaced by a Parrot rifle that kept up a steady and effective fire into the city until Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton surrendered the city on July 4.

Despite this incident, the Marine Brigade irked the overall federal commander at Vicksburg, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Reports of pillaging and other conduct unbecoming of soldiers had been brought to his attention. The frequency of such incidents throughout the life of the Brigade is documented in various reports and other writings.

Grant had another, larger beef with the Brigade: The inefficient and unequal distribution of resources. He made his opinions known in a letter to the Army’s Adjutant General, Lorenzo Thomas, about six weeks after the occupation of Vicksburg.

“Seven of the finest boats on the Mississippi River are kept for the use of this brigade, the brigade not numbering over 800 effective men,” Grant wrote. “They live on board their boats, thus keeping cavalry horses and all with them, I should think very much to the prejudice of their effectiveness and the good of the service.”

Grant requested the transfer of the Brigade to him, following which the vessels would be dispatched for general use, and Ellet’s men mustered out.

The request went nowhere. The Brigade remained independent.

Secret mission to Port Gibson

Though Grant did not get his way, he assigned the Brigade to various tasks, including a secret mission in late August. A Marine who participated in the episode told his story years after the war to journalist Delia T. Davis, a reporter who wrote about women’s wartime contributions. “One day our little battalion of four companies was ordered to steam down the river, disembark at Rodney, march to Port Gibson, and there consult sealed orders in regard to further proceedings. Imagine our surprise upon reading the instructions, to find we were expected to capture and carry back to Vicksburg as prisoners, fifty of the most aristocratic Confederate young women in the city.”

The Marines were in the dark as to the events that prompted the mission. The incursion of Grant’s army into Vicksburg and surrounding environs had liberated uncounted numbers of enslaved people. Northern volunteers traveled to the region to assist the freedmen, including female schoolteachers sponsored by abolitionist groups in New England. Rebel troops operating in lightly defended or reoccupied areas captured some number of the teachers and forced them to cook, sew and perform other menial labor for the Confederate military.

The person who decided to capture and use Southern women as hostages in negotiations for the release of the teachers is unclear. The Marines knew none of this, according to the man interviewed by Davis. He did admit, though, that orders were not to be questioned, and “we set about our bizarre and not too agreeable task.”

The Marines established headquarters at the home of a judge. Then, assisted by guides, squads of Marines fanned out across town and informed the chosen women they were to be taken to Vicksburg as prisoners of war, and that they had two hours to report to the judge’s residence. Failure to comply would result in the burning of their family homes.

All but one of the 50 women reported before the deadline. She showed up an hour late, escorted by a group of the women who petitioned the Marines not to burn her home and asked for permission to fetch her. Transporting the prisoners from the judge’s home across 20 miles of bad road was complicated by the lack of good horses and carriages. The Marines improvised by hitching decrepit horses to old buggies with plough harnesses, rope and whatever else they found.

Thus, the motley procession set off to the sights and sounds of distraught townspeople and crying captives, and finally made it to Rodney, where everyone boarded the vessels and steamed to Vicksburg. There, the women were escorted to the provost marshal, who paroled and confined them to the city limits. Some found lodging with friends. The military secured comfortable quarters for others. The episode ended about a month later with an exchange of the belles for the teachers.

Pillaging, raids and skirmishes

The Marines continued on, spending the rest of 1863 and the first half of 1864 in what amounted to a pattern of small-scale pillaging operations in Mississippi and Louisiana, confiscating horses, mules, foodstuffs and valuables. Stealing cotton—white gold—and selling it to back to federal agents. These acts roused an everlasting hatred by farmers and plantation owners that spanned generations. One unusual capture netted more than $3 million in Confederate currency and financial instruments.

Small and scattered forays against the likes of Brig. Gen. William Wirt Adams and his cavalry, and a series of skirmishes with roving bands of guerrillas proved inconclusive. The Marines transported troops during the Red River Campaign, during which they continued their pillaging ways. They were roughly handled by a Confederate brigade commanded by Acting Brig. Gen. Colton Greene in two actions, first at Greenville, Miss., and again near Lake Village, Ark.

The Arkansas action stood out as one of the largest—and the last—engagement for the Brigade. On June 4, 1864, Maj. Gen. Andrew J. Smith set out along the Mississippi River with a 6,000-man force composed of the Marines and elements of the 17th and 26th Corps to destroy Greene’s Brigade of about 800 effectives. The following day, the federals landed and disembarked in a pelting rain a few miles below Lake Village, where Greene’s men were reportedly encamped.

Company A of the Marines, with Houts in the ranks, led the way that wet morning. It soon made contact with Greene’s skirmishers and drove them back to the main defensive line. Taking cover behind anything that they could, Houts’ company faced two full rebel regiments that fired into their position. The Marines returned fire and nervously waited for the other companies, and the main Union force, to navigate through the mud and support them.

They soon arrived. Maj. Gen. Smith deployed his artillery to scatter the enemy. Instead, Greene hit back with his cannon. Smith countered by attacking with his main force and attempted a flanking maneuver that failed after Greene withdrew and left the scene. Smith’s command made its way back to the landing without accomplishing its objective, boarded the transports, and returned to its base. The battle became known as Ditch Bayou and cost the Union about 180 casualties. Greene’s Brigade suffered about 100 killed and wounded.

Dismantling the Brigade

On Aug. 7, 1864, an inspection of the MMB revealed glaring weaknesses. A report by the District of Vicksburg’s new commander, Maj. Gen. Napoleon J.T. Dana, found the Brigade reduced to 613 effectives, and had no cannon or equipment for the artillery company. He also noted that his under strength force required six transport vessels, three towboats, three tugs, two rams and six barges for the cavalry horses. U.S. Grant would surely have been appalled.

Dana’s superior, Maj. Gen. Edward R.S. Canby, did what Grant wanted to do a year earlier—he dissolved the Brigade. Arms, horses and equipment were to be turned over to the Quartermaster’s Department and the remaining men converted into an infantry regiment.

Ellet fumed. He protested on paper, a futile exercise, and ignored orders to report to Washington. Before the end of August, he departed with little fanfare for Philadelphia to await further orders that never came. Ellet resigned his commission and went on to become a wealthy and influential civic leader in El Dorado, Kan., where he died in 1895 at age 74.

More than 40 years after his death, in 1939, the Navy destroyer USS Ellet entered service. Named for the Ellets connected with the ram fleet, the vessel was christened by Elvira Daniel Cabell, a granddaughter of Col. Charles Ellet. The senior officer present, Adm. Clark H. Woodward, noted in formal comments to the officers and crew, “The Ellet will always be a top-notch fighting craft—a credit to the naval service and to those noble gentlemen whose name she bears.”

In the summer of 1941, the Ellet received orders to a new homeport in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The ship and crew were away on assignment during the Japanese attack on December 7. The Ellet served with distinction throughout World War II and was decommissioned in 1945.

Ellet’s men, shunted off to garrison duty in Vicksburg, reacted with anger. At several points, a mutiny threatened to break out. Ellet’s replacement, Col. Frederick A. Starring, arrested 48 of the mutineers, but ultimately released them on promises of good behavior.

Unhappy, idle and stripped of all the inducements that prompted them to enlist, the men collected $500 and hired Vicksburg lawyers James H. Purdy, formerly major of the 59th New York Infantry, and his partner Clark Wright, formerly colonel of the 6th Missouri Infantry, to get them discharged. The duo promised to take the case directly to the highest level of the administration and to arrange a payment of $15 for each soldier favorably discharged.

While this drama played out, Col. Starring consolidated the companies (Houts moved from Company A to Company C). The men received new uniforms, arms and equipment, but only accepted them under protest, as advised by their attorneys.

Purdy traveled to Washington and met with the president’s personal secretary John Hay, and then Lincoln himself, who punted the matter to Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana. Purdy spent months lobbying Dana, and, on Dec. 5, 1864, secured discharges for his clients.

On Jan. 19, 1865, the Marines disbanded, ending an unusual tour of duty.

Houts returned to Illinois and his father’s farm, and then moved to Missouri to farm on his own. In August 1866, he married Queen Esther Conrad and started a family that grew to include six children. The Houts family moved around a fair amount, living in Missouri, Arkansas, and finally Coles County, Ill. Beginning in 1880, Houts supplemented his income with a government pension for his Perryville wound. He died of tuberculosis in 1909 at age 64. His wife lived until 1932.

Houts’ grave marker, in Coles County’s Arthur Cemetery, only mentioned his service in his original regiment, the 123rd Illinois Infantry.

References: History of the Ram Fleet and the Mississippi Marine Brigade; The Butte Miner, Butte, Mont., June 1, 1899; Hearn, Ellet’s Brigade: The Strangest Outfit of All; Official Records of the War of the Rebellion; Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion; Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. III; Mayne, “Mississippi Marine Brigade: Misc. Operational Facts and Its Role on the Mississippi River,” mehnfamily.org; Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 17, 1939; The World, New York City, March 13, 1862.

Paul Russinoff of Baltimore, Md., has been a passionate collector and researcher of photographs from the Civil War since elementary school. A subscriber to MI since its inception, representative images from his collection appeared in the Autumn 2014 issue. He is a senior editor of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.