By Elizabeth A. Topping

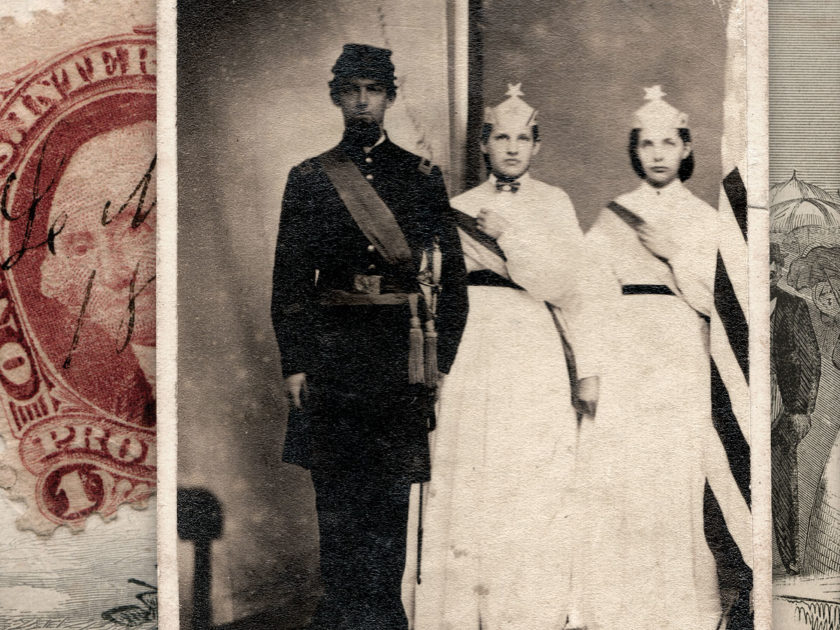

This carte de visite of an officer and ladies taken in Gettysburg, Pa., two years after the momentous battle fought in and about the town begs questions. Why are they dressed this way? Where in town did the photographer take this portrait? Why were they in Gettysburg?

After careful examination of the image and considering the evidence in context to historic events, the research trail led me to a little-remembered event with a time capsule at its center.

Let’s begin with the portrait. The first lieutenant wears a sash that may suggest he was officer of the day or another ceremonial designation. The two young ladies by his side wear Goddess of Liberty costumes with hands placed over their hearts. They stand beside an American flag. The clothing and poses are common for patriotic portraits of the time.

The location, however, is atypical. Where are they? Certainly not in a photographer’s studio. Take a look behind them. Note the open doorway. Also observe the reflective object on the floor. It is not a rug, but a floor cloth coated with a mixture of linseed oil and paint pigment. These cloths were painted to give them the look of carpet but were more durable. They were often used in high traffic areas because they were easier to keep clean than a rug.

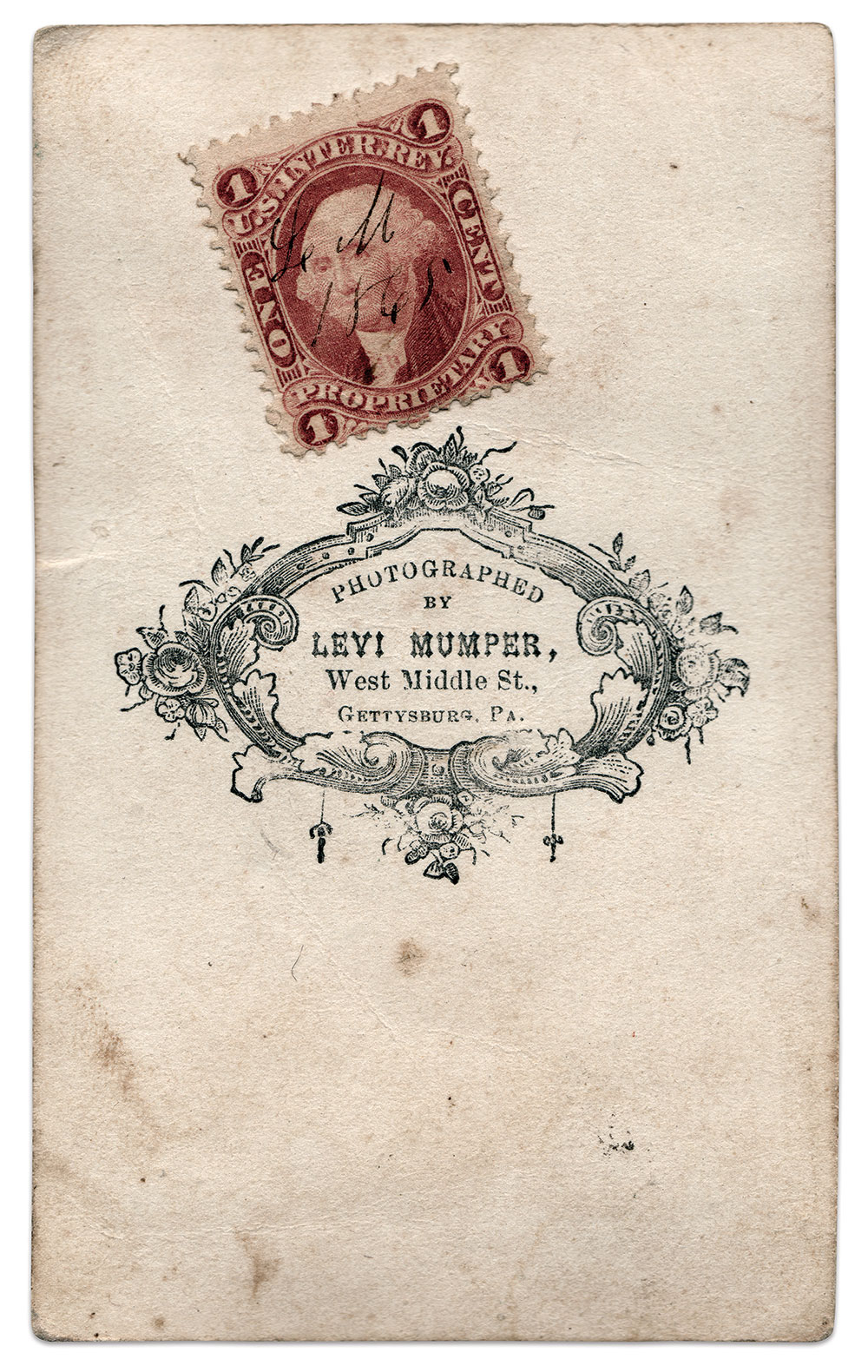

The back of the mount is imprinted with the name of the photographer, Levi H. Mumper. A veteran who had served a nine-month enlistment in the 127th Pennsylvania Infantry, Mumper (1843-1916) had a long career as a photographer. A hand-cancelled tax stamp establishes an 1865 date.

Now, we’ll consider what happened in Gettysburg in 1865 that might have inspired this patriotic portrait. The most impressive events in town this year revolved around Independence Day—the first following the defeat of the Confederacy.

Several days before the July 4 festivities, trains crowded with visitors began arriving in town. Others arrived by foot, in stages and carriages or on horseback. Good humor generally prevailed, despite the intense heat and smothering clouds of red dust.

The military joined the throng. Six companies of the 1st Connecticut Cavalry, Col. Brayton Ives commanding, camped on Culp’s Hill. They were joined by Col. William H. Telford and his 50th Pennsylvania Infantry. Lower down along Rock Creek, ten guns of Brig. Gen. James M. Robertson encamped. Bands from the 56th Massachusetts Infantry and 9th Veteran Reserve Corps also arrived in town to provide music.

By Monday, July 3, Gettysburg was jammed with people. Musical associations, Masons, Odd Fellows and other groups invaded town. According to one estimate, 20,000 people were believed to be in Gettysburg—a much larger crowd than was present at the consecration of the National Cemetery on Nov. 19, 1863.

Dignitaries also attended. They included Gov. Andrew Curtin, who had called for volunteers to defend the Keystone State against invading Confederates in June 1863, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, the victorious commander of the Army of the Potomac, and three of his subordinates, major generals Abner Doubleday, Oliver O. Howard and George Sykes.

Music and a display of rockets and other pyrotechnics filled Centre Square that Monday evening. Gov. Curtin and generals Meade and Howard made speeches.

Gettysburg lodged visitors in just about every available space. Some were invited to the David Wills home, where President Abraham Lincoln had put the finishing touches on his address.

The day of the event dawned clear and pleasant. The Soldier’s Casket, a magazine published in Philadelphia, described the scene, “Early on the morning of the Fourth, bells and cannon chimed and boomed in unison, thus performing the double duty of honoring the day itself, and announcing the approach of the ceremony. The whole time, from sunrise until the hour fixed for the moving of the procession, was spent by the assembled multitude in noisy demonstrations before the head-quarters of each distinguished General present. Perhaps the fact that this demonstration began at so early an hour, is accounted for in the other fact, that the lodging accommodations of the town were so over-taxed that hundreds of visitors were obliged to pass the night of the third on the softest sidewalks or doorsteps they could find.”

Citizen and military marshals were requested to assemble at the Adams County Courthouse on Baltimore Street at 9 am. The sashes they wore easily distinguished them; citizen marshals donning white sashes and military marshals in straw-colored silks. Could our first lieutenant have been a military marshal? As yellow reproduced in dark tones in photographs of this period, the sash he wears is consistent with a straw color.

Mumper’s gallery was just down the street and around the corner from the Courthouse. Could it be possible that Mumper loaded his photographic equipment into a cart and made his way to the Courthouse early on the morning of the 4th to set up a provisional studio inside? The marshals had limited time to have an image struck to preserve the memory of this day and they would not have had time to visit Mumper’s studio. The doorway and presence of the floor cloth in the image supports this theory.

An ad published in Gettysburg’s The Compiler at this time reinforces Mumper as a go-getter. “‘Give Him a Call’ The place to obtain a perfect Photograph or Ambrotype, executed in the best manner is at Mumper’s Gallery in Middle Street.”

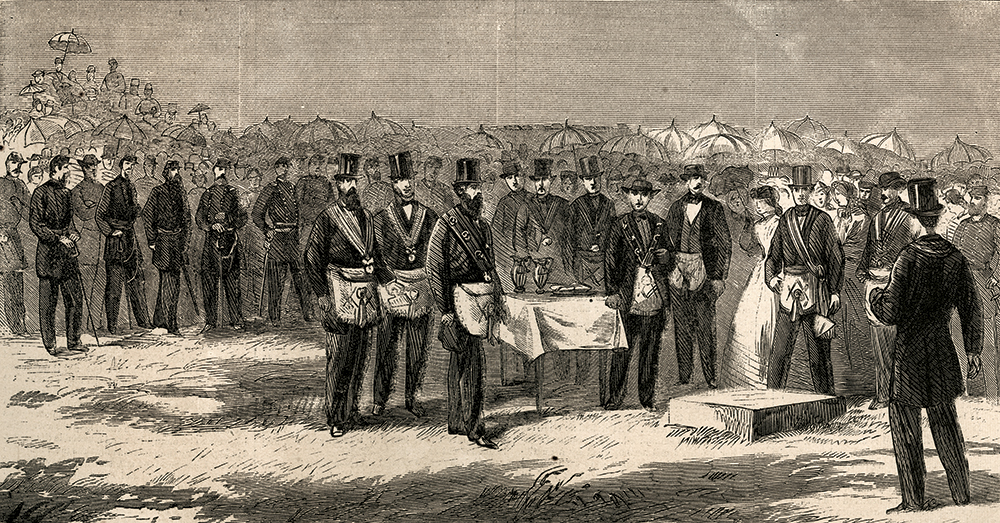

The rest of the procession formed at 10 a.m. and marched from the Courthouse up Baltimore Street to the Cemetery. Various dignitaries, including military and foreign ministers, chaplains, governors and U.S. Sanitary and Christian Commission representatives, joined the marshals. A multitude of citizens brought up the rear on foot, horseback and in carriages.

The honored few assembled on a stand in the center of the National Cemetery decorated with banners, flags, evergreens and flowers. The Soldier’s Casket described the grand solemnity of the occasion: “The Masonic Order is ranged directly in front of the staging, facing it, and a guard of soldiers at its foot. The citizens are massed on the right of these, while the ladies, except those attended by gentlemen, are massed on the left, the military occupying the centre.”

Music played, prayers spoken, and remarks made by the prominent members of the assemblage. President Andrew Johnson, unable to attend due to “severe indisposition,” sent a letter to be read in his absence.

Now we come to the centerpiece of the celebration in the cemetery: The laying of the corner stone of the Soldiers’ National Monument. The Soldier’s Casket stated its significance: “To commemorate the deeds of valor and the patriotic death of those who, at the call of their country, came forth to defend its Constitution and its laws, and to secure the perpetuation of the Union.”

Within the corner stone is held a secret: a tin box filled with articles inserted into a receptacle cut into the stone.

“We have now been called to lay the corner-stone of a monument. This monument is not a mere family record—not the simple memorial of individual fame, nor the silent tribute to genius. It is raised to the soldier. It is a memorial of his life and noble death.”

The Compiler listed the contents: “Among the documents were the Constitutions of all the States whose soldiers fought for the Union in the Gettysburg battle; Constitution of the United States; President’s Emancipation Proclamation; President Lincoln’s personal messages and artifacts; list of soldiers who were killed, and the names of those buried in the Cemetery, together with relics of the Army of the Potomac; an account of the battle of Gettysburg, and a copy of the consecration ceremonies.” A group of items contributed by Pennsylvania were contained in a separate copper box inscribed with its name. Michigan placed its items in a 9 by 5 by 4-inch copper box labeled “State of Michigan, 1865.”

The keynote speaker, one-armed Maj. Gen. Howard, noted in his oration, “We have now been called to lay the corner-stone of a monument. This monument is not a mere family record—not the simple memorial of individual fame, nor the silent tribute to genius. It is raised to the soldier. It is a memorial of his life and noble death. It embraces a patriotic brotherhood of heroes in its inscriptions, and is an unceasing herald of labor, suffering, union, liberty, and sacrifice.” This was followed by several speeches and the benediction.

The majority of visitors left after the official ceremony and continued to filter out of town the next morning. On July 6 the military departed, leaving Gettysburg quiet once again.

I am confident this portrait dates on or about July 4, 1865, and that it pictures a military marshal attended by the Goddesses of Liberty, who numbered among those that participated in the procession and ceremony at the laying of the cornerstone and time capsule for the Soldiers’ National Monument in the National Cemetery.

In its own way, this carte de visite is a time capsule; a gift from Levi Mumper discovered long after the events of a hot July day in 1865.

References: The Compiler, Gettysburg, Pa., July 10, 1865; New York Herald, July 24, 1863; The Soldier’s Casket, Philadelphia, Pa, August 1865.

Elizabeth A. Topping has been a reenactor and living historian for more than 25 years. Her collection and research work focuses on the social and material history of the Civil War years. Her initial study centered on the subject of prostitution, which ultimately led to research on abortion, birth control and childbirth, female job opportunities and working conditions, medical treatment for poor and insane women, class and sex restrictions imposed on 19th-century females, the roles actresses played in society, and the parts women played in aiding the war efforts. Elizabeth enjoys sharing her expertise and artifacts for use in television programs, museums, magazines, conferences and roundtables.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.