By Ronald S. Coddington

On May 3, 1855, the council of the Photographic Society of London voted unanimously to investigate a burning question that preoccupied its membership.

Why do paper photographs fade?

The Society appointed a Printing Committee of six to tackle the problem from two angles. First, to collect and examine prints across a wide spectrum, from badly faded to pristine condition. Second, to determine the best method to produce high-quality, durable prints.

The Society also approved a modest sum to embark on the long-term study. Within a week, the organization received a generous donation to support the committee from Prince Albert, the consort of Queen Victoria. The Royals, fascinated by photography and proud of Britain’s contributions, numbered among the medium’s most passionate patrons.

A formal announcement of the Society’s action made the front page of the May edition of its monthly journal. It noted, “The question is one of vital importance, and has already occupied the attention of both the producers and collectors of photographs.”

The question remains relevant to today’s collectors and conservators.

Head-spinning technology upends photography

The timing of the Society’s action followed a series of head-spinning technological advancements that upended the photography industry. Since the advent of commercial photography in 1839, the daguerreotype reigned supreme. These silver-plated masterpieces set a high bar for quality and artistry. Unmatched in beauty and in great demand by the public, they held a virtual monopoly in the marketplace.

While the daguerreotype held the public’s fascination as a means of portraiture, some imagined another role for photography. About the same time the Society laid its plans to study fading, an essay in The Practical Mechanic’s Journal declared, “We must turn our attention to the employment of the photographer for purposes of a more utilitarian class than those with which we usually associate his labours.” Specific examples were cited: Replacing a heavy wagonload of goods with photographs of the items, and adding likenesses of individuals to identification documents, such as passports, hunting licenses and visiting cards.

“Look over the magnificent album that ornaments the parlour centre table and observe how many pictures are in a fading condition, if not already spoiled by the effects of time. … We may find, some day, to our sorrow, that the shadow has not long survived the substance.”

These dreamers glimpsed the future of photography not in artisanal daguerreotypes, but in mass-produced positive paper prints from a negative—a process developed by William Henry Fox Talbot, a British physicist.

Talbot had made his discovery in 1834—five years before the daguerreotype—but chose not to go public due to the complexity of his method. While he experimented with ways to streamline his process for commercial use, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre perfected his procedure and announced it to the world.

Talbot soon followed with the announcement of his Talbotype process, commonly referred to as Calotype, a hybrid term based on the Greek words “beautiful” and “impression.” Though it never quite matched the beauty of the daguerreotype, the Calotype achieved commercial viability and enjoyed a degree of popularity.

Disciples of Talbot improved on his negative-positive process. One of these individuals, Britain’s Frederick Scott Archer, introduced a technique involving a glass plate coated with a light-silver collodion emulsion in 1851. It significantly increased the quality of the negative.

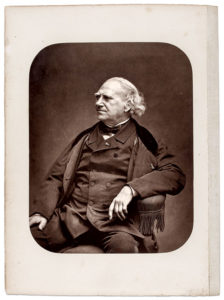

Another believer, French merchant and inventor Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard, made a contribution in 1850 that dominated photography for most of the next half-century.

He invented albumen paper.

Albumen paper: designed for mass production

Blanquart-Evrard explained the process in his 1851 book, Photographie Sur Papier. His method involved a fine sheet of paper coated with albumen (egg whites) and salts that made it light sensitive in a silver nitrate solution. The dried treated paper, when placed against Archer’s collodion coated-glass negative, was exposed in the sun and developed in a darkroom in a chemical bath, which yielded a superior print.

The quality of albumen paper, rapid development time, and ability to make vast numbers of images from a single negative revolutionized photography—and contributed to the daguerreotype’s decline. George Ville, who wrote the introduction to Photographie Sur Papier, observed, “In the current state of photography we cannot obtain from the same negative more than three or four positive tests per day. With the new process of Mr. Blanquart-Evrard, we can raise this number to three or four hundred so that in a factory where 30 or 40 negative proofs would operate daily one could easily produce 5 to 6 thousand positive proofs which would be delivered the same day at a very low price. We can therefore say without exaggeration that the photographic industry is now a fait accompli and that this important fact is the work of Blanquart-Evrard.”

Ville continued, “Blanquart-Evrard’s work puts photography at the service of the industry. From now on we will produce photographic prints with as much ease as lithographs and engravings, and the time is not far off when book publishers will illustrate the finest works with photographs.”

The era of mass production of photographs had arrived.

Alison Nordström, an independent curator of photographs, underscored the importance of Blanquart-Evrard’s invention in a 2014 interview for George Eastman House. “The photograph becomes really important, not just conveyer of knowledge and information, but a shaper of knowledge and information. And it’s the albumen print that made that possible because it was precise, it was detailed, it was cheap, and it could be mass produced and distributed easily.”

The yellowing problem

All photographic formats suffered limitations. The daguerreotype and its variants, and the ambrotype and tintype, were direct positives and only one could be produced. Talbot’s original salted paper Calotype prints developed from paper negatives lacked the sharpness of the daguerreotype.

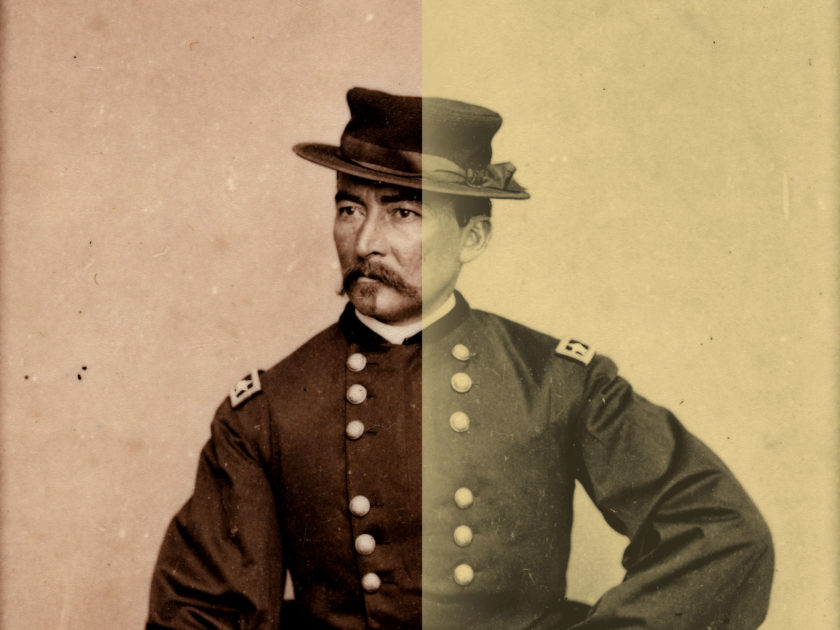

Blanquart-Evrard’s albumen paper and Archer’s collodion plates solved the single-image problem of the daguerreotype and the sharpness issue of the Calotype. Egg whites added a desirable semi-gloss finish. Early issues with tonal flatness of albumens were addressed by the addition of gold chloride after experimentation with other chemical compounds. Gold chloride resulted in deep, rich tones in hues of brown, purple and red. Photographers gravitated to purple hues of the aubergine, or eggplant, as the de facto standard.

Albumen paper also had its limitations. The thinness caused it to curl into tight rolls post development, and so the finished prints had to be mounted to cardstock with adhesive. Its biggest drawback, however, was a yellow discoloration described by one observer as a “cheesy unpleasant hue.” This color change occurred as the print faded from the desired purple to sepia. Some prints exhibited the telltale sign of fading soon after creation, while others held their preferred color over time.

Photographers fretted about the permanence of paper images. Collectors expressed similar concerns. The action by London’s Photographic Society to establish the Printing Committee was as much about solving the fading issue, as it was to head off negative public perceptions. The May 30, 1855, edition of The Manchester Examiner and Times stated as much in a news brief. “The photographic society has just taken a very important step which all lovers of this most wonderful art must admit to be in the right direction.”

Meanwhile, albumen paper emerged as the standard for positive-negative photography. In 1854, it became commercially available to meet the needs of the rapidly expanding marketplace. This same year also marked the filing of a French patent for a camera capable of making multiple exposures of a single view on one plate. The inventor, André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, and the photographic cartes de visite from his newfangled camera had great potential to expand the reach of photography by challenging the daguerreotype as the portrait format of choice.

But would fading thwart progress and kill albumen paper?

“The supposed author of every fading mischief”

The Printing Committee’s first report appeared on New Year’s Day of 1856. It attributed fading to London’s environment, pointing to humid air polluted with hydrogen sulfide. The Committee recommended coating prints with a layer of varnish to shield the image surface from airborne contaminants. It also advocated for a higher quality, less moisture-absorbing adhesive to paste prints to mounts.

Following on the heels of this report, Marc Antoine Auguste Gaudin, editor and publisher of the photography journal La Lumiere and the author of the handbook Traité Pratique de Photographie, pointed to residual silver from the development process as the cause of fading.

Another writer later described silver as “the supposed author of every fading mischief.”

Gaudin was correct. The combination of trace silver and sulfur in egg whites interacting with hydrogen sulfide resulted in overall yellowing of the photograph. It was especially noticeable in the highlights.

Over the next decade, industry leaders focused their efforts on minimizing the yellowing of albumen prints. Suspicions that the combined fixing and toning bath might contribute to the problem prompted a move to separate baths that improved print quality. Using fresh chemical solutions and the introduction of rigorous washing of prints—good development hygiene—became a mantra among photographers.

Despite efforts by meticulous photographers dedicated to perfecting their craft, the pursuit of long-lasting, high-quality prints remained elusive. The chemicals with which they worked, and the complexities of the multi-stepped production process, proved an ongoing challenge to rookie and veteran photographers alike. Fading could be minimized, but not eradicated.

Some never came to grips with the fading problem and questioned the idea of paper photographs, even after Disdéri’s carte de visite had supplanted the daguerreotype as the dominant format during the first half of the 1860s. In his 1865 essay “On the Durability of Photographs,” American inventor and chemist Silas R. Divine lamented, “Photographs on paper are a convenience which the public seems to demand, although certain to be cheated with pictures that are not permanent. Look over the magnificent album that ornaments the parlour centre table and observe how many pictures are in a fading condition, if not already spoiled by the effects of time. Surely, when an album photograph is the only portrait we have of a lost friend, we are cherishing a very frail memento, and we may find, some day, to our sorrow, that the shadow has not long survived the substance. Photographers know this: what one of them would exchange a Daguerreotype of a dear relative for the best carte de visite ever taken? The public will know it, and at no distant day refuse to have any more such trash as they get now-a-days.”

The disappearing shadow

Albumen paper survived into the mid-1890s, when other paper types emerged and quickly dominated the market. By 1900, the new papers made albumen obsolete. It had outlived its creator, Blanquart-Evrard, who died in 1872, and the carte de visite, which began a slow slide into oblivion after the cabinet card became the format of choice in the mid-1870s.

As the decades of the 20th century ticked by, surviving albumen prints suffered further deterioration. In addition to the yellowing and general fading detailed here, other sources affected the print surface. The adhesive used to affix the print to the mount compromised the albumen paper from the backside. The cardstock mount, a sandwich of two outer layers of fine paper and a middle layer of cheap pulp paper, also caused problems.

Annual and seasonal fluctuations in humidity and temperature added to the deterioration, disrupting the semi-gloss finish, and leaving behind a web of fine cracks visible with a magnifying glass or the naked eye. In some instances, entire flakes of the print area broke off, especially along unprotected edges of the albumen print. Exposed residual silver, or silvering, resulted in a mirror-like sheen. Mold or fungus left telltale signs of its presence in the form of irregular reddish-brown stains, known as foxing.

The net effect of these natural forces dulled the richness and depth of the original semi-gloss, purple-hued prints, leaving in its wake a flat, lifeless image. Retouched areas and tinting added by the photographer or a staff colorist to enhance the sitter’s likeness were largely unaffected, and now appeared garish and heavy-handed in context to the faded print.

During the latter part of the 20th century, studies of albumen prints painted a dire picture of surviving examples created more than a century earlier. In his 1980 work, The Albumen & Salted Paper Book, author James M. Reilly noted that 95 percent of albumen prints produced in the 1850s displayed moderate to severe yellowing. The remaining five percent appeared to have maintained white highlights, though further study revealed the presence of yellowing. Albumen prints created after 1860 did not fare much better: 85/15 percent. “Few albumen prints today at all resemble their original image color,” Reilly concluded. Moreover, he estimated that by the year 2055 “not a single albumen print will at all resemble its original appearance.”

On preservation

Measures can be taken to prevent or slow Reilly’s grim estimate from becoming fact. Conservators, museum professionals and private collectors all have a critical role to play in preserving these irreplaceable visual artifacts from the pioneer days of photography.

The same environmental factors identified by the 1855 Printing Committee in London still impact albumen prints today: air pollution, humidity and temperature. Natural light and poor storage are also major contributors that can hasten the death of a paper photograph.

To combat these contaminants and corrosives, temperature-controlled environments, minimal exposure to light and inert storage materials that pass the Photographic Activities Test (PAT) are critical. Among the many excellent guides to consult include Care, Handling, and Storage of Photographs by the Library of Congress and the Preservation Self-Assessment Program offered by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Special thanks to Rachel K. Wetzel of the Library of Congress for her assistance in preparing this story for publication.

References: The Journal of the Photographic Society, May 21, 1855; Blanquart-Evrard, Photographie Sur Papier; George Eastman House, The Albumen Print – Photographic Processes Series; Rappaport, “Victoria, Albert & their Patronage of Photography,” Stories from the Footnotes of History; Lea and Wilson; Photographic Mosaics, an Annual Record of Photographic Progress, 1867; James, The Book of Alternative Photographic Processes; Sutton, Photographic Notes, Vol. I; New York Times, July 12, 1994; Reilly, The Albumen & Salted Paper Book; Photographic News, 1865; Cycleback, Photograph Identification Guide; Stulick and Kaplan, The Atlas of Analytical Signatures of Photographic Processes: Albumen; Wahl, The Culinary Darkroom: Albumen Photographic Prints; International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) and the Council on Library Resources, Information Leaflet: Care, Handling, and Storage of Photographs; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Preservation Self-Assessment Program.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.