By Adam Ochs Fleischer

If you haven’t had the opportunity to peruse the Library of Congress’ digitized collection of Civil War glass plate negatives, I encourage you to do so. The high-resolution files, available in the TIFF format, are extraordinary. The granular detail allows the viewer to zoom in almost microscopically and pick out details that are not apparent at first glance. Small things, such as flies on horses, mud-caked boots, and stitched repairs on uniforms, all make for a revelatory experience. Especially compelling (at least to me), are the candid shots of soldiers unaware that their photos were being taken. To view, often with perfect clarity, the weary faces of battle-worn soldiers feels almost voyeuristic

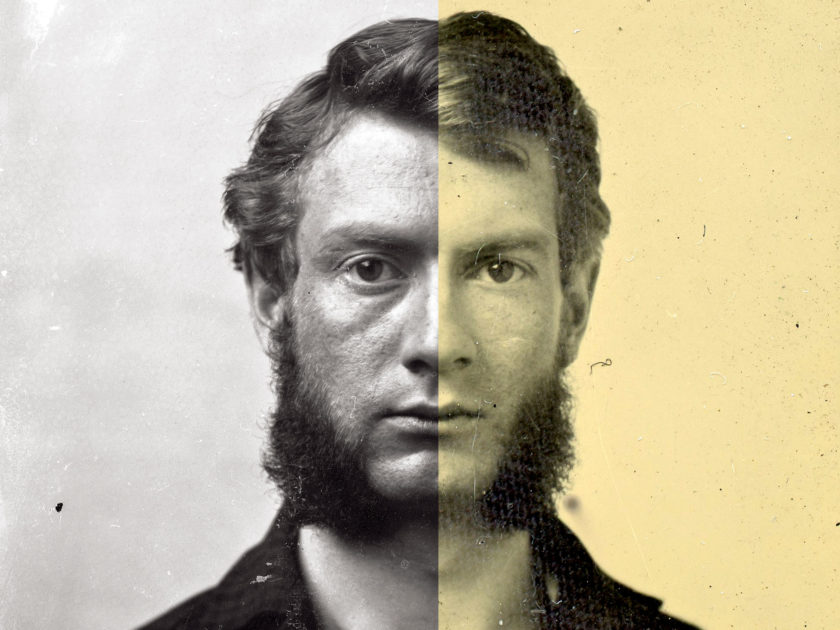

There is one posed portrait in the collection that I’ve always found particularly arresting: That of Lincoln assassination co-conspirator Lewis Powell. Taken by Alexander Gardner aboard the ironclad Saugus or Montauk, Powell is manacled and leans against a turret. While widely known and published, viewing the TIFF file online is nothing short of breathtaking. Details such as the beard stubble on Powell’s face and the texture of his sweater material contribute to dramatic effect, such that the viewer might expect Powell to step out of the photo itself and demand to be uncuffed. Powell appears so modern, so real, that in his upward gaze directly into the camera’s lens makes it easy to become lost entirely in the moment of Gardner’s seconds-long exposure.

For those of us who study and collect hard images, cartes de visite, and albumen prints from the Civil War era, it is hard to look at these scans and not become envious of their superior clarity. But are they in fact superior?

Common ground: Glass plate negatives and ambrotypes

An ambrotype involves a glass plate negative made positive by a black background. Its collodion emulsion differs from a conventional wet plate glass negative so that they appear clearly against a black background.

These two emulsions, however, share a common characteristic: The amount of visual information they contain is essentially the same. This is abundantly clear in the Library of Congress’ negatives. But some of the ambrotype’s detail is lost when it is turned positive.

Several months ago, I began experimenting by scanning ambrotypes that lack a coated black varnish as negatives. I used an Epson Perfection V550 model scanner’s “film negative” feature, which can be utilized by removing the white layer aboard above the glass flatbed.

I found the results impressive. One image of a sailor I scanned nearly made my jaw drop. I considered it a nice image viewed normally as a positive, but as a negative it transformed into a striking portrait—much the same as Lewis Powell. The texture of the subject’s skin was now visible. In his eyes, you could see the reflection of the photographer. And, you could practically count the number of hairs on his face. It was an incredible transformation.

As I scanned more images, I discovered that the results varied by the degree of photo subject focus, how far away from the camera they sat or stood, and the condition of the photo itself. While small emulsion imperfections are easily overlooked when viewing an ambrotype or tintype, they become quite glaring in a negative scan. Still, the visual highlights of most examples richly improved, and investigating the new found detail of these scans has proved as rewarding as exploring those held by the Library of Congress.

Practical application for photo sleuths

For collectors and historians, this process could clarify details previously too blurry or faint to decipher. The belt buckle, thought to be just a bit too out-of-focus even under a jeweler’s loop, might now be easily recognized as a Virginia state seal. The regimental brass number on a kepi, previously considered too grainy to make out, might now be clear enough to read legibly. A universe of small discoveries waits to be made.

A market for prints?

In the art world, one often hears the remark that the relatively low price ceiling of Victorian-era images in the marketplace relies on their size. Even a full-plate image’s wall-power becomes diminutive when compared to most high-resolution prints generated from modern negatives and film regularly exhibited in museums and sold at auction. As evidenced by my scans, it seems conceivable that comparable prints could be generated from clear glass ambrotypes.

This observation begs a question: How desirable would they be?

This observation begs a question: How desirable would they be?

I suspect the answer is that strong markets for ambrotype prints will unlikely materialize. Without removing the painted black backings, which I do not endorse, the possible limited availability of suitable candidates presents a practical restraint. Also, it’s difficult to know whether the material itself would be appealing to vernacular art collectors. While the New Orleans red light district portraits of photographer E.J Bellocq are in vogue, would a print of a 19th century blacksmith or antebellum Southern belle hold the same cachet? Say nothing, too, about copyright. Without opening that Pandora’s box, suffice it to say that the legality of establishing a copyright claim is not currently clear.

Adam Ochs Fleischer is passionate researcher of Civil War photography and an admitted image “addict.” He began collecting in high school, and quickly became obsessed. An MI Contributing Editor, he authors Behind the Backdrop. Adam hails from Delaware, Ohio, but now lives in Chicago.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.