By Kurt Luther

Photo sleuthing is, at its core, a process of elimination. We start with a mystery photo whose subject could be any of the three million soldiers who fought in the Civil War. Then we use clues and context to narrow down possibilities.

Was he Union or Confederate?

What ranks did he hold?

What regiments did he join?

Where did he enlist and where did he fight?

With plenty of hard work and luck, the sleuth hopes to narrow the large pool of candidates to an airtight identification.

We built the Civil War Photo Sleuth (CWPS) website to help with this process of elimination. The site aims to leverage the complementary strengths of humans and computers. Computers are better at quickly searching through huge piles of images or text, while humans are better at considering details and context.

CWPS provides two forms of automation. First, face recognition, which compares thousands of soldier portraits and returns only the most similar-looking faces. And second, filtering searches thousands of military records to return only the soldiers whose service fits the specified criteria.

But how well do these automated techniques actually work? In this column, I report on a series of tests run by Vikram Mohanty, a Ph.D. student on the CWPS team, to measure the effectiveness of face recognition and filtering on different types of Civil War soldier photos. Based on these results, I offer some practical advice for more successful photo sleuthing with CWPS.

Selecting the test photos

We started the test by selecting a set of photo pairs, i.e., two different photos known to be the same soldier. We could then measure how well CWPS was performing by searching one photo in the pair, and seeing where (if at all) the second photo appeared in the search results.

We wanted to make sure the set of photos was broad enough to represent the many different types of soldiers that users try to identify on CWPS. We settled on seven categories based on several factors that we suspected might influence the software’s performance, including photo format, military service, and race. The categories were: (1) duplicates, e.g., copies of the same CDV; (2) artworks, e.g., lithographs from regimental histories or painted portraits; (3) low-ranked (i.e., enlisted or NCO) Union soldiers; (4) high-ranked (i.e., commissioned officer) Union soldiers; (5) low-ranked Confederate soldiers; (6) high-ranked Confederate soldiers; and (7) black USCT soldiers.

We took several steps to ensure the photo pairs were accurate and high quality. They all came from established public collections with well-known, irrefutable identifications. Also, they were all wartime portraits, as best as we could tell—no cadets or veterans—to avoid confusing the face recognition with age-related differences. Finally, at least one photo in each pair (often both) showed the soldier in uniform, so that we could tag and filter results based on visual clues like clothing and rank insignia.

“While computer algorithms can filter out noise and highlight the best options, only humans can provide the careful analysis and synthesis required for an airtight identification.”

We endeavored to collect five photo pairs for each category. We soon discovered there is no easy way to find such photo pairs. And for some categories, especially low-ranked Confederates and USCT soldiers, few examples appear to survive. After consulting many reference books and a plea for help in the Civil War Faces group on Facebook, we found what we needed: 35 photo pairs across the seven categories, or 70 photos total.

To prepare for the tests, we ensured one photo from each photo pair was in CWPS. If users had not already added it, we did so ourselves, tagging the photo and creating a soldier profile with the correct military records.

Testing the face recognition

We tested the face recognition by simply uploading the second photo in each pair for all categories, without any help from human expertise, tags or filters. Then, we inspected the search results, focusing on three key questions. Did the correct match appear in the search results? If so, how high did it rank in the search results? Finally, how many incorrect matches (false positives) also returned in the search results?

We tested the face recognition by simply uploading the second photo in each pair for all categories, without any help from human expertise, tags or filters. Then, we inspected the search results, focusing on three key questions. Did the correct match appear in the search results? If so, how high did it rank in the search results? Finally, how many incorrect matches (false positives) also returned in the search results?

First, we tested duplicates. Duplicates show the exact same view of the soldier, though possibly a cropped or vignette version, so we expected them to serve as a kind of ceiling or best-case scenario. Sure enough, duplicates performed best of all the categories. For all five pairs, the correct match was included in the search results. Better yet, every correct match was ranked No. 1. However, searches for duplicates also returned plenty of false positives—an average of 611 per pair.

Next, we tested artworks. Since these were hand-made by artists, they were not perfect likenesses. Artists may have changed certain features for aesthetic purposes (or unintentionally). Therefore, we expected artworks to perform worse than actual photo pairs. But because such portraits were common in period newspapers and regimental histories, we hoped they would provide some utility. For artworks, face recognition included the correct match in all but one of the five cases. However, the correct match never ranked number No.1, and often ranked much lower, averaging No. 185. Artworks also returned many false positives—more even than duplicates—averaging 728 each.

Finally, we tested how well pure face recognition performed on white soldiers versus black (USCT) soldiers. Face recognition algorithms struggle with modern photos of non-white people, often for preventable reasons such as biased training data, so we wondered how Civil War-era photos would fare. For black soldiers, face recognition included the correct match in all five cases, compared to 26 out of 30 cases for white soldiers. For both black and white soldiers, the correct match was ranked No. 1 in all but one case (William Matthews and John S. Mosby, respectively). False positives for black soldiers were an order of magnitude lower than white ones (averaging 40 vs. 477, respectively), but still higher than expected, given that less than 2 percent of soldiers in the CWPS database are black.

Testing the filtering

To test CWPS’s other major automated tool, filtering, we conducted two rounds of searches for each photo pair. First, we applied the “army” military filter (Confederate or Union, depending on the soldier’s uniform) and searched. Second, we added the “rank” military filter, based on the rank insignia visible in the soldier’s photo, and repeated the search. For example, a photo depicting a soldier with a dark frock coat and three chevrons on the sleeves would receive the “Union” (army) and “sergeant” (rank) filters, causing CWPS to limit the search results to soldiers with that military service record. For these tests, we used the 25 white and black soldier pairs, excluding the duplicate and artwork categories.

As noted above, face recognition by itself returned the correct match in search results for 16 of the 20 white soldiers and all five black soldiers. Furthermore, all the correct matches were ranked No. 1 except for one white soldier (Mosby) and one black soldier (Matthews). For these two exceptions, we looked at whether filters improved their rankings. For all of the photos, we also looked at two other criteria: Whether the filters inadvertently removed correct matches from search results, and the number of incorrect matches (false positives).

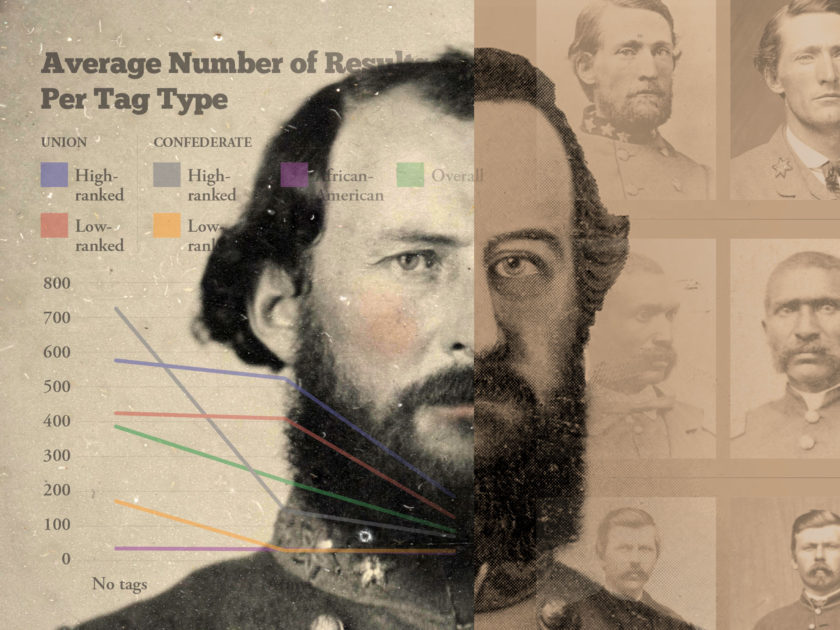

We found that applying the “army” filter benefited all categories of soldiers, but the main advantage was culling false positives for Confederates. The average number of incorrect matches for high-ranked Confederates fell by more than 80 percent (from 726 to 141); for low-ranked Confederates, the average reduction was more than 85 percent (from 175 to 25). For both white and black Union soldiers, the effect of the “army” filter was, in contrast, quite modest, ranging from 4-10 percent. Eliminating false positives, unsurprisingly, also improved rankings for the two correct matches not already ranked No. 1. The “Confederate” filter improved Mosby’s ranking from No. 148 to No. 78, while Matthews’ “Union” filter bumped his ranking from No. 7 to No. 3. No correct matches were excluded.

Applying the “rank” filter was also largely beneficial. Notably, it reduced false positives by an average of about between 50-75 percent for all soldier categories, except one, low-ranked Confederate soldiers, where it made little difference. The average remaining search results ranged from 24 to 179, a much more manageable number. The rank filter also improved rankings for Mosby and Matthews, raising them to positions No. 12 and No. 2, respectively. Unfortunately, there was also one case, Joseph E. Johnston, where the rank filter eliminated a correct match, due to incorrect military records entered by a CWPS user.

Tips and takeaways

Our tests found that CWPS’s face recognition and filtering tools can substantially narrow possibilities, but depending on the type of photo and subject, some techniques are more effective than others. Below, I summarize some key takeaways and tips to help photo sleuths get the most out of these features.

TIP 1: Pay special attention to the top-ranked search result, especially for duplicates.

Our tests found that CWPS’s face recognition, by itself, works pretty well. For 25 of the 30 photo pairs (excluding artworks), face recognition returned the correct match and ranked it No. 1 among a database of over 28,000 possibilities. This performance is even more impressive given that 25 of these pairs showed different views of the same soldier, and represented a diversity of armies, ranks and races.

TIP 2: Review the entire batch of search results, especially for artworks.

As well as face recognition alone performed, it was not perfect. Face recognition matched four of the five artworks, but their rankings averaged No. 185. In four other cases, there was a matching photo of a Union soldier in the database, but face recognition completely missed it. Two more examples occurred where face recognition included the correct match in search results but ranked incorrect matches above it. A user would have to scroll through 148 candidates to find the correct match for John S. Mosby.

Further, face recognition always returned many incorrect matches (false positives). We tested identified photo pairs, so we already knew which search result was the correct match. Users seeking to identify an unknown soldier, of course, will not know, and diligent sleuthing requires them to examine most, if not all, potential matches. Given an average of 477 false positives for white soldiers, this is no small task. Although Thomas Clark’s correct match was ranked No. 1, his search results included 902 other candidates.

TIP 3: Apply filters for both army and rank, especially for Confederates.

Fortunately, our tests also found that CWPS’s filtering feature does a good job of eliminating false positives, helping the user focus attention on the most promising candidates. Applying a combination of army and rank filters reduced false positives by half or more. Filters sometimes improve rankings and almost always preserve the correct match. But as the Johnston example shows, they are beholden to the accuracy of CWPS’s military records added by users.

As always, we encourage photo sleuths to think of the CWPS software, including face recognition, as a starting point in their research, rather than a one-stop shop. While computer algorithms can filter out noise and highlight the best options, only humans can provide the careful analysis and synthesis required for an airtight identification.

Kurt Luther is an assistant professor of computer science and, by courtesy, history at Virginia Tech. He is the creator of Civil War Photo Sleuth, a free website that combines face recognition technology and community to identify Civil War portraits.

Military Images is America’s only magazine solely dedicated to Civil War portrait photography. Not a Military Images member? Consider our special introductory offer for new members only: Subscribe to Military Images magazine for $24.95 a year and receive four quarterly issues PLUS a free upgrade to our digital edition, which includes PDFs of each issue that are yours to keep and unlimited access to our premium web edition—a $5 savings. Subscribe and become a member now.

© Military Images Magazine. The contents of this page may not be reproduced in whole or part without the written consent of the publisher. Views expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent those of Military Images or Military Images, LLC.