By Kraig McNutt

On Jan. 16, 1864, Union veterans of the famed Irish Brigade gathered for a magnificent banquet at Irving Hall in New York City. Proud sons of Ireland escorted ladies with mourning badges pinned to their dresses to pay respects to those who had died in battle for their adopted country.

Irish Brigade officers organized the event for non-commissioned officers and privates of the unit. Old and new colors of the Brigade’s original 88th, 69th and 63rd New York regiments decorated the platform area of the grand hall. Thirteen banners bearing the names of battles in which the Brigade had fought during the war, including Malvern Hill, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, adorned the room. Ale, cider and whiskey punch flowed as servers laid out a sumptuous feast before the honored guests.

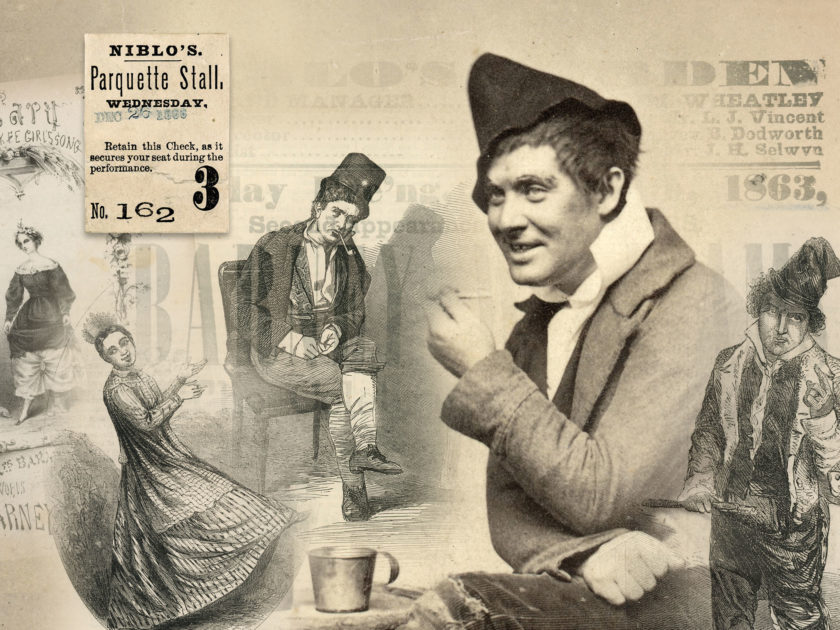

Following speechmaking by Irish Brigade commander Thomas Francis Meagher, subsequent toasting ensued, as did a funeral dirge for the honored dead. Then stepped forward a performer who needed no introduction—Barney Williams. The renowned Irish songster, actor and comedian belted out the popular tune, “Bowld Sojer Boy.”

There’s not a town we march thro’But ladies looking arch thro’The ranks to find their joy,While up the street, each girl you meetWith look so sly, will chat “My eye,Oh isn’t he a darling, the Bowld Sojer Boy!”

The talented Williams is the subject of one of the greatest rags to riches stories in mid-19th century America. Born Bernard O’Flaherty in 1824 in County Cork, Ireland, his parents sought a better life for themselves, and no doubt their son, as they settled in Manhattan in 1831.

The Williams family moved to the Sixth Ward in Manhattan’s Five Points—think The Gangs of New York movie—in 1831, joining tens of thousands of other sons of Eire. Irish immigrants that arrived in America during this period typically sought to escape famine in their ancestral lands. But after they landed in their new country, they soon faced another deathly challenge: the 1832 cholera outbreak. Irish and German immigrant populations were hit hard by the pandemic, which killed more than 3,500 in New York City alone, equivalent to more than 100,000 people today.

Young Williams toiled in odd jobs on the filthy streets of Manhattan to help the family put food on the table. He worked as an errand boy, a fruit seller, and, according to one source, the very first sidewalk newspaper boy in America when The Sun debuted in 1832. If Williams sold all of his 100 newspapers each day, he would have netted 33 cents, or about $10 today.

Williams had much higher aspirations than just running errands for printers, grocers and street vendors. Most likely, Barney got his first taste of the amateur theatre world when he was about 10 years old. Newsboys and bootblacks founded their own tiny playhouse in a Five Points tenement basement on Baxter Street, close to where Barney lived.

By age 12 in 1836, Williams was running errands for the Franklin Theatre, and earning $5 a week as an usher. It was there that he learned many “negro songs and dances.” His first real break came that same year with an invitation to fill in for an actor who had taken ill, getting a professional speaking role in The Ice Witch. The theatre manager considered his performance good enough to keep him on permanently. Williams was immediately entrusted with Irish character roles, such as Pat Rooney in the farce Omnibus. In addition, he performed Irish songs, danced the Irish jig, dabbled in blackface minstrelsy, and even worked for P.T. Barnum in his Moral Lecture Room, a main feature of the fabulous museum. Williams also worked many of the bawdy theaters in New York City, and on the road in theaters in Philadelphia, Pittsburg, Baltimore and New Orleans.

Fortune smiled again on Williams in November 1849 when he married the widow Maria Pray Mestayer. According to one story, he proposed to her during a break in the action on stage, and married during the next break in the same play. Maria, a child actor who emerged as a talented theater star, counseled Williams to stop accepting “negro roles,” and focus on Irish characters, especially the Irish Paddy Ragged Pat.

Williams took his bride’s advice, and within a few years they became millionaires by today’s standards. At the height of his career during the mid-to-late 1850s, Williams earned more than $600 a night, or about $18,000 today. Not bad, considering a carpenter made about $500 a year. During the winter of 1852-53, the couple performed in California and made the equivalent of $350,000 today.

Capitalizing on their fame and at the height of their stardom in 1855, they embarked on a singing tour in Great Britain as the Irish Boy and Yankee Gal. Over the next two years, they earned $100,000—or $3 million today. They performed for the British Royal Family on more than one occasion.

The famous stage artists returned to America and opened to great success at the famous Niblo’s Garden in New York. They continued to pack houses in major cities even after the Civil War engulfed the country.

Williams’ reputation as the best-known Irishman on stage did not go unnoticed by fellow actor John Wilkes Booth. The star of Othello, Macbeth, Hamlet and other Shakespearian masterpieces, Booth turned his nose up at the lowbrow Irish comedy championed by Williams. No doubt Booth might have been a little jealous of Barney’s impressive success. In an 1861 letter to a banker friend, Booth noted that he had watched Williams rehearse in Cincinnati and remarked, “It is rough to see such trash.”

President Abraham Lincoln, by contrast, was a fan of popular comedies. He attended at least two performances by Williams. The first, on Feb. 24, 1863, occurred at Grover’s Theater on Pennsylvania Avenue near the Willard Hotel, at Williams’ personal invitation. Lincoln accepted the request, and watched Williams in The Lakes of Killarney; or, The Brides of Glengariff.

Lincoln might have nodded his head in agreement with the critique of one newspaper: “A more genuine Irish peasant never walked the boards.”

Evidence suggests the president and the Irish comedian met that night. Soon after, Williams sent a note to Lincoln requesting a Naval Academy appointment for his nephew, James Kelly. Lincoln however, could not fulfill the entreaty, at least initially, responding, “I do not think I can put your nephew among the first ten appointments now soon to be made. I really wish to oblige you; but the best I can do is to keep the papers, and try to find a place before long.”

Lincoln did make good on his word more than a year later though, when he wrote to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, “About a year & half ago I almost, if not quite promised Mr. Barney Williams that his nephew James Kelly should be sent to Naval School. I shall be really obliged if you can find a place to put him in. If not now, let it be done as soon as it can be.” Kelly received an at-large appointment from the president on Oct. 5, 1864. But there is no evidence that Kelly ever became a navy officer.

The number of soldiers and sailors entertained by Williams during his many wartime performances in Washington is unavailable. But it can be fairly stated that he provided much-needed laughs to many military men seeking a diversion from the harsh realities of the seemingly endless war. Records show that Williams performed for New York regiments on at least two occasions, in addition to his singing for the Irish Brigade in January 1864. He engaged with members of the 47th New York Infantry as they steamed down the Hudson River in October 1863, and also with the 64th New York Infantry aboard a barge on the Potomac River.

Williams and Maria continued their careers after the war. Aside from a 4-year stint as a theater manager on Broadway in the late 1860s, he spent the majority of his time on stage. Williams’ health began to decline about this time, and his final illness started in March 1876. Newspapers across the nation carried bulletins for weeks as his life hung in the balance. Williams died of a stroke on April 25 at age 53. His remains were buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn. Williams was survived by his mother, a 13-year-old daughter, and his beloved wife. Maria outlived Williams by 35 years. The Yankee Gal retired from performing after Barney’s death, living until 1911.

A Philadelphia newspaper writer praised his work and life. “No man ever personated an Irish peasant with greater fidelity to nature than Mr. Williams. He felt for their situation, and the sound of his voice and the tear in his eye told that it was the man and not the mere stage figure of one. This is true stage action, and this Mr. Williams had in the life of his profession. In private life Barney was open-handed, generous and humane, and he used his wealth to help the poor, succor the needy and raise the downtrodden.” The writer continued, “Hundreds of persons will read this announcement with moistened eyes when they remember the kindnesses which Barney Williams quietly and unostentatiously scattered in their path.”

No doubt aged Civil War veterans remembered him fondly for the cheer he brought them late in the war.

Kraig McNutt has been blogging on the Civil War at CivilWarGazette.com since 1995. He has collected Civil War ephemera and given talks on a myriad of Civil War subjects for more than 20 years. He and his wife live in Colorado Springs, Colo.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.