By James S. Brust

Today’s photograph collectors have a term to describe cartes de visite of art, celebrities, scenes and other non-personal portraits tucked into albums—filler CDVs. The term assumes these cartes did little more than fill a slot in an empty album page when a better image of a family member or friend was not available.

In fact, filler CDV is a misnomer. Produced in large numbers, these images attracted enough interest to earn them a spot in family albums alongside the personal portraits of loved ones. Evidence suggests that these photographs played an important part of the visual culture of the time. Yet, collectors generally dismiss them today. The term first appeared in MI in 2002, and in Google searches in 2010.

In fact, filler CDV is a misnomer. Produced in large numbers, these images attracted enough interest to earn them a spot in family albums alongside the personal portraits of loved ones. Evidence suggests that these photographs played an important part of the visual culture of the time. Yet, collectors generally dismiss them today. The term first appeared in MI in 2002, and in Google searches in 2010.

To appreciate these overlooked images, one needs to place them in context of the times.

The advent of photography in 1839 was miraculous, allowing literal and lasting pictures of the natural world for the first time. But these early formats—daguerreotypes, ambrotypes and tintypes—were relatively expensive and yielded only a single image, a personal visual document that could not be widely shared.

While these early images changed visual culture, the introduction of the carte de visite in the U.S. about 1860 went even further. This efficient process allowed people of modest means to have affordable portraits made of themselves and their families, and receive multiple prints to exchange with loved ones. Then, as now, it was natural for people to want images of their friends and family as reminders and keepsakes. The Civil War intensified the want to have a likeness made, as soldiers desired to take along images of loved ones, and, faced with the very real danger of never returning, leave behind their own.

As the craze for cartes de visite took hold, specially made albums appeared with slots to hold them. Photographers produced pictures of a non-personal nature as an alternative to family and friends: politicians, military leaders, actors and other newsworthy individuals, scenic places and battlefields, to name a few. The public purchased them in huge numbers. The popularity of these images created a significant revenue stream for photographers eager to boost their income.

Production of these non-personal cartes ranged from large firms to individual photographers. Major galleries, with the advantage of name recognition and urban locations, had easier access to high profile individuals who might be induced to pose. Enterprising photographers of limited means turned to easily available subject matter. Inexpensive popular prints were a ready source of such imagery. It was a simple matter to buy or even borrow a Currier & Ives print, for example, tack it to the wall, photograph it, and then produce multiple cartes for sale.

These works of art were often copied without permission, or “pirated,” a common practice in that era that drew little censure. They would then be issued anonymously with no mention on either side of the mount of the publisher of the copied print, or the photographer who had photographed it. There might or might not have been a pre-printed or even hand-written title on the carte de visite mount, with varying degrees of similarity to the actual title of the copied print. Any identification on the reverse was apt to be that of the distributor of the carte, rather than the maker.

Here, we examine one part of this huge marketplace—works of art, specifically paintings, prints, drawings and cartoons. Some are fine while others crude; some carefully identified but many anonymous. They were inexpensive and readily available, carrying fine artistic images, patriotic symbolism, comforting humor and important political and social messages. These images became quite popular, circulated widely, and had an importance in the visual culture of that era belying the seemingly unimportant term “filler.” As part of the history of photography during the Civil War era and a direct reflection of the popularity of the images portrayed, they are worthy of collection, preservation and study.

Civil War Art

Lithographs by John Henry Bufford

American lithographers produced a substantial share of this country’s popular imagery, and those prints provided inviting subject matter for pirated cartes de visite. Unique among them was the Boston firm of J.H. Bufford, who issued cartes of his own prints. On Guard, Father and Son, left, is a portrait reflecting the nature of Civil War fighting units, where family members and neighbors volunteered to serve together. Bufford’s logo on the print is visible in the photo, and reinforced by words printed on the mount below the image.

A pair of Bufford prints, The Sleeping Sentinel and The Reprieve, center and right, related the story of a soldier sentenced to death for falling asleep while on guard duty, and then pardoned by President Lincoln. Lincoln commuted a number of death sentences during the war.

Campaign Sketches by Winslow Homer

One of the most famous American artists of the 19th century, Winslow Homer first gained recognition during the Civil War through reproductions of his battlefield sketches as wood engravings in Harper’s Weekly and lithographs published by Louis Prang in Boston. These two cartes were pirated from Campaign Sketches, a set of Homer drawings issued as lithographs by Prang in 1863. The Coffee Call, right, exactly matches the title of the original published print, but does not have any information elsewhere on the mount. The other is marked on the reverse with a crude stamp “Published by F.E. Thurston, Philadelphia,” and a printed title The Pass Time. It remains unclear if Thurston worked as a photographer, or simply a dealer distributing cartes produced by another source. The actual title of Homer’s print is A Pass Time, Cavalry Rest. This carte was put to interesting use. A pencil inscription, faintly visible in the illustration, reads, “146 Regt. on duty, they never get tired.” A 146th infantry (not cavalry) regiment from Oneida County, N.Y., served during the war. Perhaps one member personalized this carte as a reminiscence of his service, or possibly a number of these were colored, inscribed and distributed to members of the regiment as a collective remembrance, for proud display in their family albums.

The humor of Thomas Nast

The humor of Thomas Nast

The caricatures by acclaimed illustrator Thomas Nast ran the gamut, from satire of Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall to a creation of Santa Claus still used today. Nast drew humorous Civil War home front images that appeared on cartes de visite. All three pictured here feature children playing at war, a lighthearted diversion from the actual horror of the battlefield. Unusual among artists at that time, he appears to have issued some of them himself. All three clearly bear standard copyright wording. The Colored Volunteer, center, and The Commander in Chief, on the right, have the back mark of J. Hall & Co. of New York City. The original copied artworks are clearly Nast’s wash drawings. It is unclear if Nast engaged Hall to issue these cartes or vice versa. Either way, these were not pirated. The Domestic Blockade, on the left, followed a different route. The 1863 copyright statement by Nast appears on the verso, but the title is on the reverse along with the logo of the New York Photographic Company, one of the major producers of non-personal cartes. This version appears not to be a wash drawing, but rather the Currier & Ives lithographed version of the same image. Currier & Ives issued lithographed versions of all of these Nast drawings, which in turn were pirated in the usual way. In all the examples, Nast received credit, and presumably income, from sales.

The Empty Sleeve

This carte of the 1866 J.C. Buttre print, The Empty Sleeve: What a Tell-Tale Thing is an Empty Sleeve, by Adelaide R. Sawyer, was issued with only partial title and no artist credit. In an age when amputations were a common sight, they might have been viewed as a badge of honor. Though this soldier appears safely at home, and his beautiful child, though curious, is not horrified, the forlorn look on his face indicates that his scars will not heal easily.

The Civil War art of John R. Chapin

The Civil War art of John R. Chapin

Harper’s Weekly artist John R. Chapin spent a month on duty with a New Jersey state militia light artillery battery that crossed into Pennsylvania during the Confederate invasion of the North in 1863. (See Jerseymen by John Kuhl in the Winter 2019 issue of MI.) Chapin’s art also appeared as engraved book illustrations, some of which were pirated as cartes. Pictured here, clockwise from top left, are Death of Wadsworth, Rally Around the Flag, Who’ll Care for Mother Now, and Mother I’ve Come Home to Die. None have any information printed on the mounts, but all include pencil inscriptions, mostly on the reverse, identifying the title of the print and the name of the artist.

To Arms! Freemen to Arms!

The mount on this tinted carte was trimmed almost to the lower border of the photographic image. The part of the mount removed revealed the title, To Arms! Freemen To Arms!, painted by William Morris Hunt, and copyrighted by him in 1862. The photographer and publisher was John P. Soule of Boston, Mass. The original painting, The Drummer Boy, now at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, served as the basis for this artwork. It is not clear if the actual painting or a print version was photographed.

Home on a Furlough

Issued anonymously, this carte was photographed from an 1864 print, Home on a Furlough, after a painting by Christian Schussele, engraved by John Sartain, and published by Bradley & Co. of Philadelphia. A dedication beneath the title on the original print reads: “To the loyal mothers, wives and daughters, of our country, this engraving is respectfully dedicated.” Despite the absence of all this information on this presumed pirated carte, this scene might appeal to any family who had a loved one fighting in the war.

President Abraham Lincoln

The Lincoln family

Though President and Mrs. Lincoln were photographed separately or with one or more of their children, they never posed together. Images of the entire Lincoln family were supplied only by the printmakers, and worked their way onto cartes de visite and into albums. Here are cartes of two 1865 prints of the Lincoln family, which were in demand after the assassination. His untimely death spurred a market for Lincoln imagery—a phenomenon repeated almost 100 years later following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

The horizontal anonymous carte, top, was copied from a lithograph titled Abraham Lincoln & Family by Henry Atwell Thomas, and published by William C. Robertson of New York. A widely known photograph by Mathew Brady provided the source for the lithograph of Lincoln and his son, Tad. Another Lincoln son, Willie, who died in 1862, sits next to his mother. Oldest son Robert, leaning on his father’s chair, rounds out the scene.

Prest. Lincoln and Family was copied from an 1865 engraving by A.S. Walter after F. Schell, and published by John Dainty of Philadelphia, Pa. The central element of Lincoln and Tad comes from the same Brady photo, with Mary and Robert in a more compact arrangement. Willie appears only as a portrait on the wall. Based on the number of surviving examples, this image represents one of the most popular non-personal cartes ever produced.

The assassination

The Assassination Of President Lincoln, At Ford’s Theater, Washington D.C., April 14th 1865, top, was pirated from a Currier & Ives lithograph. Nathaniel Currier and other popular printmakers had offered views of newsworthy disasters for a quarter of a century when events unfolded at Ford’s Theater. Though their illustrations were often fanciful, the public wanted to “see” what had happened as quickly as possible. The only way photography could compete was to reproduce those prints.

Death Bed of Lincoln is but one of a multitude of similar views produced by printmakers and copied by photographers. The dramatically composed, imaginary scene stretched the room, and filled it with dignitaries past its realistic confines. This one is copied from a lithograph by A. Brett & Co., and published by Jones & Clark of New York. All figures are identifiable. In the foreground on either side, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton sternly eye the viewer. Mary Lincoln kneels and weeps over her husband, while their son, Robert Lincoln, cries into a handkerchief just beyond the head of the bed.

Exaltation

President Lincoln’s tragic martyrdom just days after the Confederate surrender at Appomattox left the Union grief stricken, and in need of comfort that their leader and all who had perished had died in a noble cause. It would reassure those in mourning that Washington, the nation’s first great leader, would be the one to welcome into heaven the man who had now achieved equal stature as a national hero. The two embrace, top, in Washington & Lincoln (Apotheosis). The nation’s first commander-in-chief holds a wreath above the head of the 16th president. This carte was photographed and published in 1865 by the Philadelphia Photographic Company, after a painting by Stephen James Ferris.

Washington Crowning Lincoln offers a variation on the same theme. Published in 1865 by Boston photographer George W. Tomlinson, Washington and Lincoln appear above the clouds, backlit by dramatic rays of sunlight. More awkwardly posed than in the preceding view, Washington again holds a wreath. This representation contains patriotic symbolism as well, with an eagle, motto, shield and drapes supporting the image.

Emancipation

Emancipation

In the center of this tinted carte stands the allegorical figure of Liberty, flanked by a black man and woman linked by an American flag. Liberty points to a scroll, presumably the Emancipation Proclamation. This example was pirated. Other cartes of this image show it was painted by G.G. Fish and photographed and published by photographer John P. Soule in Boston in 1863.

Freedom to the Slaves

This pirated carte of an Currier & Ives lithograph leaves only the title visible. The original included a caption: “Proclaimed January 1st 1863, by Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States. ‘Proclaim liberty throughout All the land unto All the inhabitants thereof.’” Perhaps the photographer omitted this wording because it would have been hard to read once the image was reduced to the smaller carte de visite format.

Political Cartoons

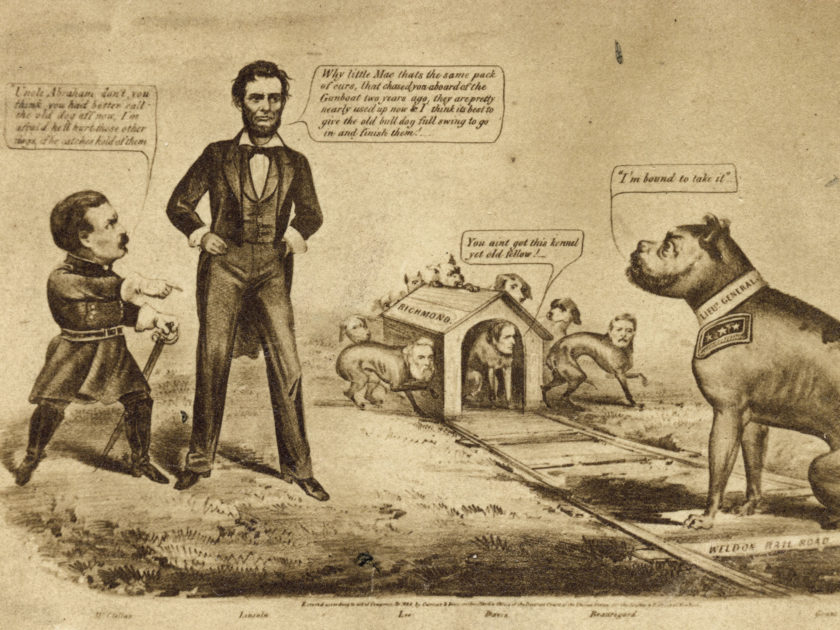

The Old Bull Dog on the Right Track

This 1864 Currier & Ives political cartoon is another pirated carte. The bulldog is Ulysses S. Grant, poised on a Confederate rail line that leads to a doghouse marked “Richmond,” where a group of cowering dogs including Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis and P.G.T. Beauregard await. On the left, a diminutive George McClellan urges caution but Abraham Lincoln says, “… I think it’s best to give the old bull dog full swing to go in and finish them!” Likely issued in support of Lincoln during the 1864 election, someone thought it important enough to circulate this image as a carte, even though the caption might be difficult to read.

The capture of Jefferson Davis

When Union troops captured Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Georgia on May 10, 1865, he reportedly threw his wife’s overcoat around his shoulders as he attempted to flee, leading to rumors that he had tried to escape disguised as a woman. Artists lampooned him in a proliferation of cartoons, such as these Currier & Ives images pirated as cartes. These caricatures humiliated the Southern leader, and expressed the rage felt in the North against the defeated Confederacy.

I’m Not to Blame for Being White, Sir

This pirated carte of a satirical anti-Sen. Charles Sumner cartoon was issued as a lithograph during the 1862 mid-term elections. Some of Sumner’s constituents in Massachusetts were displeased with their senator for appearing more concerned with abolition than with their needs. In the image, two begging children approach the well-dressed and handsome Sumner. Sumner hands a coin to the black child, and ignores the white one. Original impressions of the lithograph are extremely rare, which might lead to the conclusion that it was unpopular. But the appearance of this pirated carte provides evidence that it circulated more widely than realized.

Edgy humor

Beauties of the Draft

This uncommon carte of a drawing or print criticized the draft—or at least spoofed one way in which some evaded it. The patient on the left tells the doctor that he has back pain and can’t serve. When he takes off his coat to be examined there is a $50 bill tucked under his suspenders, which the doctor is taking. Their dialog, printed below the title, reads “Doctor I’m weak in the back.” “Yes, I see it—can’t go—too delicate.” The image is copyrighted 1863, the year that marked the beginning of conscription in the North and draft riots in New York City. The individual who filed the copyright, Austin Augustus Turner, worked as a photographer for the studio of Daniel Appleton in New York City. He almost certainly took this photograph. But his name on the copyright line suggests that he might also have been the artist.

Possible variation on Attack on the Enemy Breast Works

Any title and caption that had originally appeared on the mount of this carte was lost when the owner trimmed it. The back mark identifies Boston lithographer John Henry Bufford as its maker. It also includes a note stating that the illustration is “from his original subject,” though occasionally he used that mount to show artwork of others.

Though the title is missing, the content is clearly risqué. A handsome Civil War soldier gropes the bosom of a pretty young woman clad in a low-cut dress that also reveals her ankles. Behind the fence another young woman, fully clad with bonnet and clothing covering her shoulders (perhaps the soldier’s wife, girlfriend or relative) looks on in horror. At least one other popular lithograph at the time took a similar theme, titled Attack on the Enemy Breast Works, and this one may have had a comparable title. This carte serves as a reminder that risqué subjects can be found in albums.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.