By Ronald S. Coddington

The officers of the warship St. Louis arrived in the bustling Moroccan port city of Safi on an August day in 1863 to a warm welcome. The bashaw, or governor, greeted the Americans on the Atlantic beach where they landed. He and an entourage escorted them to his palace and regaled them with a formal tea in the ancient Moorish custom.

The Americans sipped the soothing minty drink inside the executive mansion full in the realization that they were the first U.S. vessel of war to visit the North African port. Their number included Albert Leary Gihon, the charming, intelligent, even-tempered and good-natured ship’s surgeon from Philadelphia.

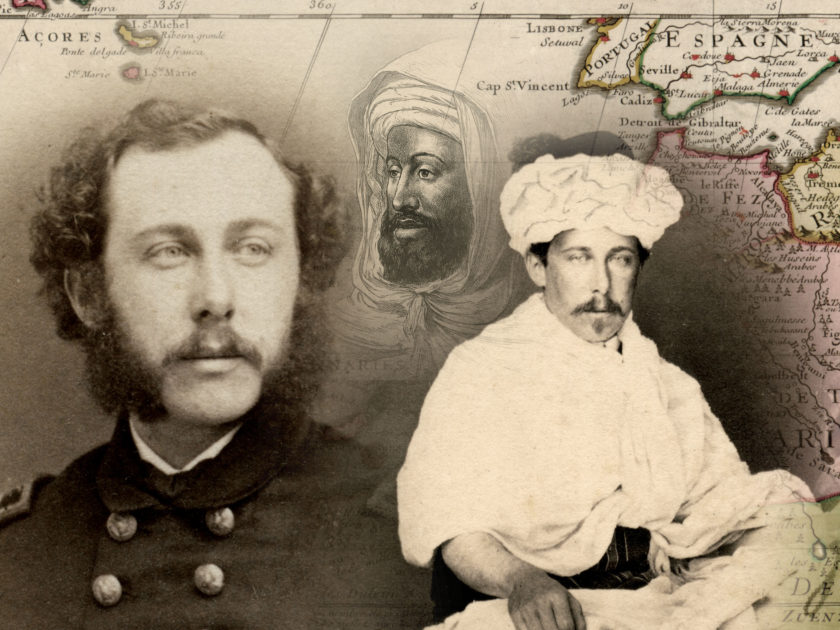

It may have been about this time that Gihon posed for his portrait, sitting cross-legged and dressed in a turban, robe and sandals. The style of clothing is consistent with the Jebala people of the mountains in the northwestern region of the country. He holds a strand of Muslim prayer beads in one hand, his fingers arranged in a way that suggests an awareness of the practice of counting beads during the recital of three prayers, 33 times each.

Below the portrait is his name in Arabic. The inscription, جيحون, or Jayhoun, is a derivation of Gihon, the name of one of the four rivers that flowed through the biblical Garden of Eden.

Why Gihon dressed in traditional Jebala garb is unclear. His character and background suggest several motivating factors: intellectual curiosity, cultural awareness, the intrigue of an exotic location, and a desire to document his travels.

There’s one more—a spirit of adventure. Gihon hailed from a family of globetrotters who dwelled at the intersection of science and art in a young and rapidly expanding United States.

Chief among them was his father, John Hancock Gihon, Jr. His story reads like a four-act play. A medical school graduate, he never practiced his profession. Infected with California fever, he arrived in San Francisco in 1849 and watched his fortunes rise and fall as a newspaperman and bookseller. In Bloody Kansas, he acted as a personal secretary to the territory’s governor and his close friend, John White Geary.

His younger brother, John Lawrence Gihon, followed in their father’s footsteps. After a physical issue prevented his entrance into the U.S. Naval Academy, he landed in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. The move proved a stepping stone to a notable career as a photographer that included memorable images of Confederate prisoners of war at Fort Delaware.

Gihon’s own story began in 1833 in Philadelphia. He was born the first of three children to his aforementioned father and mother, Mary Jane, a woman of which little is known other than a slow and painful death in the prime of her life. Gihon received a rigorous education and had the credentials to show for it: a medical degree from the Philadelphia College of Medicine and Surgery and a Master of Arts from Princeton. In between the two degrees he lectured on chemistry and toxicology. All of this occurred before he turned 22 years old. One admirer later noted that Gihon “earned his spurs as a practical man, as an earnest, conscientious, worker. More than all, he had been appreciated for his humane qualities.”

Armed with science and art degrees, Gihon continued his education when he entered the navy as an assistant surgeon in the spring of 1855. Over the next five years, as the political situation at home deteriorated, Gihon cruised the high seas on two notable assignments. The first, aboard the Levant, included a tour of duty with the East India Squadron. Here he came under cannon fire when protecting Americans caught in the middle of hostilities between the British and Chinese that became known as the Second Opium War. The second, on the brig Dolphin, involved a gunboat diplomacy mission to Paraguay. The Dolphin joined a convoy of warships in a show of force in support of ultimately successful negotiations to seek redress for an 1855 incident during which the Paraguayans shelled a navy vessel and killed a sailor.

In April 1860, Gihon landed at Savannah, Ga., where he married Clarissa “Clara” Montfort Campfield, a young woman four years his junior. How and when they became acquainted is not exactly known. Clara’s genealogy yields two possible clues. Her father, Charles Henry Campfield, hailed from New Jersey, where the Gihons lived for a time. The two families may have become acquainted during this period. One of her younger brothers, John Shellman Campfield, became a physician and may have met Gihon through a professional connection.

Any attachment the two physicians might have had ended with the start of the Civil War. Dr. Campfield cast his lot with Georgia and the Confederacy. He spent the majority of the next four years as an army surgeon in and about Savannah.

When the bombardment of Fort Sumter plunged the country into war, the Gihons lived in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he had been assigned to the naval hospital. A couple weeks after rebel forces occupied Sumter, Gihon received orders to report to the brig Perry. The vessel sailed to Florida for duty with the newly established Atlantic Blockading Squadron, part of the strategic Anaconda Plan to suppress the rebellion by shutting down key Southern ports. The Perry scored early successes when it captured two blockade runners and prevented a couple more from delivering supplies.

On July 8, 1861, the Perry left the blockade for repairs and became an unlikely historical footnote. Gihon and the rest of the crew arrived at the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C., on the eve of the First Battle of Bull Run. When word arrived of the stunning federal loss and retreat into the capital city, the Perry sailed into the Potomac to guard against possible Confederate attacks that never materialized.

Diplomatic wars heat up

Meanwhile, international tensions stirred as Union and Confederate statesmen traveled abroad to negotiate strategic alliances with nations large and small. The diplomatic wars were fought on multiple fronts—the high seas, exotic ports of call, remote cities and distant capitals.

One of its earliest and best-known actions occurred in the Atlantic between Cuba and the Bahamas on Nov. 8, 1861. On that day, Union Capt. Charles Wilkes and his San Jacinto stopped the British mail ship Trent and removed Confederate envoys James Mason and John Slidell. Wilkes transported the men to Fort Warren on Georges Island, which guarded the entrance to Boston harbor and served as the Confederate prison. Official Washington and the public initially rejoiced at the news, but the enthusiasm faded with the realization that the diplomats had been taken without legal precedent and against American values. The British government protested, demanding the release and restoration of the envoys. President Abraham Lincoln carefully weighed the matter and in consultation with military and political leaders ordered the release of the men before the end of the year. Lincoln’s decision brought an end to what became known as the Trent Affair.

Gihon headed to diplomacy’s front lines early in the new year. On Jan. 3, 1862, he received orders to report to his native Philadelphia to join the St. Louis, a 20-gun sloop with a compliment of 125 sailors. The date of the orders held meaning for the ship’s commander, Matthias C. Marin, a Union-loyal Floridian, for it marked his 30th year in uniform.

Gihon left Clara, now pregnant with their first child, in New York. Parting had to have been sweet sorrow. There were, however, advantages to life at sea. Gihon found the air and overall climate aboard ship most agreeable, and he contributed his excellent physical and mental health to the efficacy of what he termed “ocean therapy.” In fact, he presented a paper on the subject later in his career.

Gihon soon learned the particulars of the mission. On Jan. 24, 1862, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles directed the St. Louis to proceed across the Atlantic to the archipelago of the Azores. The lush volcanic islands marked the westernmost point of a geographic triangle that included the Canary Islands to the south and the Strait of Gibraltar to the east. Welles indicated they could pick up correspondence from the U.S. minister at the Portuguese capital of Lisbon.

Welles allowed a single exception for leaving the tightly defined area: “You will not go out of these limits unless in search of piratical vessels, upon eligible information received by you of the appearance of such vessels at any particular point.”

Five days later, as the St. Louis prepared to leave Philadelphia, Welles changed the first stop from the Azores to the Spanish port of Cadiz, where the elusive rebel steamer Sumter had been spotted. Commanded by the wily Raphael Semmes, the sleek steamer successfully raided the Union merchant fleet in execution of Confederate strategy to weaken enemy commerce.

The St. Louis departed Philadelphia on January 31 in pursuit.

The Tangier Affair

As the St. Louis made its monthlong journey across the Atlantic, a diplomatic drama played out in the Triangle reminiscent to the Trent Affair. The events occurred in the Moroccan port of Tangier, a strategic gateway between Africa and Europe. Morocco and the United States had enjoyed a positive relationship for the better part of a century thanks to the efforts of Sultan Muhammad III, a strong proponent of global trade. In 1777, he opened ports under his rule to the fledgling United States, and in doing so became the first country to recognize the new nation. A Treaty of Friendship formalized the relationship in 1786.

Flash forward eight decades. On Feb. 19, 1862, a French vessel bearing two Southerners landed in Tangier on a refueling mission for the Sumter, which had run out of coal. They were Henry Myers, a Georgian who had resigned his U.S. navy commission and joined the Confederate service as paymaster of the Sumter, and Alabamian Thomas T. Tunstall, a former U.S. Consul in Cadiz removed by President Lincoln. The senior American diplomat in Tangier, Consul James De Long, became aware of their arrival and immediately contacted Moorish authorities. They dispatched a military guard who intercepted the Southerners and delivered them to De Long, who had them chained in rooms of the U.S. Consulate.

On February 26, all hell broke loose in the streets of Tangier when several hundred European ex-patriots marched on the Consulate to free the Southerners.

De Long fired off a dispatch to his superiors. While he waited for instructions, European diplomats protested the arrest and imprisonment of Myers and Tunstall. On February 26, all hell broke loose in the streets of Tangier when several hundred European ex-patriots marched on the Consulate to free the Southerners. De Long, who happened to be on his way back with a few officers from the newly arrived U.S. warship Ino, charged the Europeans and forced them to fall back.

The mob soon returned to complete its mission. Fortunately for De Long, his interpreter had already sent word to the Moorish minister, who immediately called on European diplomats to get their subjects off the streets and dispatched a guard to protect the U.S. Consulate—a show of faith on the part of the Moroccans.

De Long reacted with an ultimatum to the Moroccans to open the port that had been temporarily closed, to allow a detail of Marines from the Ino to march into the city, and to provide protection for his consulate. De Long topped it off with a threat—he gave the Moroccans an hour to meet his demands or else “I would strike the American flag and quit the country.”

The Moroccans, true to their friendship with the U.S., complied. By the end of the day, Myers and Tunstall were marched through Tangier as thousands of spectators watched. They were confined aboard the Ino for a trip to Fort Warren in Boston, where Mason and Slidell had been imprisoned after the Trent Affair.

De Long’s threatening ultimatum to friendly Morocco ended his tenure in Tangier. The Lincoln administration moved quickly and decisively to recall him, unlike the weeks-long period of soul-searching and shifting of public opinion during the Trent Affair. The new consul, Jesse H. McMath, a 30-year-old Ohio attorney, soon departed for his new post.

Resolution in the cases of the captured Southerners followed before the end of the summer. Government officials deported Tunstall, a political prisoner, to his native Alabama with orders not to return to the North for the duration of the war. The military held Myers as a prisoner of war—a rare case of a Confederate captured on foreign soil—and exchanged him for a Union officer.

The Sultan’s Decree

Back in Morocco, Consul McMath acclimated to his new post. Along the North African coast and elsewhere in the Triangle, Gihon and the crew of the St. Louis remained vigilant to deter Confederate raiders from destroying commercial vessels.

On the U.S. homeland, the war raged unabated. The momentous Battle of Antietam marked the end of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s first invasion of the North. President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation to clarify his administration’s position on slavery shortly after, bringing freedom to millions held in bondage.

The document acknowledged the “unprovoked and wicked rebellion, which is seeking the destruction of the republic that it may build a new power, whose corner-stone, according to the confession of its chiefs, shall be slavery.”

Two months later, in March 1863, Congress clarified its position on foreign intervention in America’s domestic problems with a set of resolutions. The document acknowledged the “unprovoked and wicked rebellion, which is seeking the destruction of the republic that it may build a new power, whose corner-stone, according to the confession of its chiefs, shall be slavery.” Building on the moral high ground of human rights, the document summarized the hope of rebel leaders for support from foreign powers to maintain the flow of cotton into their factories. It further declared, in blunt terms, that the U.S., backed by a just cause, would crush the rebellion in time. Moreover, that while the Union army and navy performed its duty, any attempt by another nation to encourage the rebellion in any way would be viewed as an unfriendly act.

The government distributed the document to its army of diplomats across the globe. On April 10, 1863, McMath received his copy and arranged a meeting to share its contents with Muhammed Bargash, the Moorish Minister of Foreign Affairs. A pragmatic man some 20 years senior to McMath, Bargash worked as a businessman and accountant prior to accepting the ministerial appointment a year earlier,

McMath met Minister Bargash the following day. “I called, and was very kindly received; and having my interpreter with me, I caused him to read to his excellency, in the Arabic language, the resolutions of Congress,” McMath reported to Secretary of State William H. Seward. McMath then recounted the words of support from Bargash, who confirmed that “his Majesty’s government had for a great many years been the sincere friend of the American nation.” Bargash added that if Morocco found itself at some future point in a domestic rebellion he expected the U.S. government would abide by the same spirit of non-intervention.

Satisfied that he and Bargash stood on common ground, McMath turned his attention to the very real possibility that a Confederate raider might enter a Moroccan port by force or negotiation with sympathetic parties. He requested that the Moroccans not allow rebel ships to enter the country’s ports on pain of seizure. Thus began an exchange of views through the spring and summer of 1863.

As negotiations proceeded, the St. Louis patrolled the Triangle with a new commander at the helm. George Henry Preble, a 47-year-old career officer, had been cashiered the previous summer after the rebel cruiser Florida escaped him at Mobile Bay. Congress intervened on his behalf and overturned the dismissal in early 1863. The St. Louis was Preble’s first active duty assignment since his reinstatement.

Preble, along with Gihon and the rest of the crew, made several stops along the Moroccan coast in the summer of 1863, including the memorable visit to Safi on August 4, where they drank tea in the bashaw’s palace. Preble reported that during the festivities, a supply of beef and bread arrived for the crew of the St. Louis, courtesy of the bashaw. The visit ended later that day and was declared a victory all around. Even European consuls in Safi expressed their satisfaction with the Americans, telling Preble that word of their good deeds would reach the Sultan, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Rahman, also known as Muhammad IV. He had ascended to the Moorish throne four years earlier at about age 29.

On Sept. 23, 1863, Foreign Minister Bargash informed McMath that the Sultan had made a decision regarding American rebels. Bargash distributed orders in the Sultan’s name to the bashaws and other government leaders in Moroccan ports “not to receive any one of the insurgents, so-called Confederate States, for the reason that they are not known to us, nor is there any consul who can make them known to us, therefore they shall not be admitted.”

So much for Confederate hopes for friendly ports along this vibrant trade route, and for European efforts to persuade the Sultan otherwise. A jubilant McMath forwarded the royal decree to Washington.

McMath also passed the news to Preble, who notified Navy Secretary Welles. In his communication, Preble observed that the St. Louis had visited Moroccan ports in August, and therefore “it is reasonable to suppose that her salutes and appearance assisted to the success of these negotiations.”

And what of Gihon’s image in Jebala garb? Considering the content of the portrait and his character in context to the military and political climate, might the pose have generated goodwill that contributed to the diplomatic triumph in Morocco?

Epilogue

The St. Louis continued its Atlantic cruise into 1864, chasing enemy raiders along the way. Preble had a second chance to capture the Florida at the port of Funchal on the Portuguese island of Madeira—but again the enemy vessel slipped beyond his reach. At one point, a cautious Preble ordered his sailors to remove the shot from their guns for fear that they might accidentally fire at the Florida in violation of the port’s neutrality. This act drew the ire of Secretary Welles, who admonished Preble, “Had the Florida violated the neutrality of the port and fired into the St. Louis the honor of our flag would have been compromised, and the act as it stands is humiliating to an officer.”

Preble remained in the navy and retired as rear admiral in 1878. He is best remembered for his extensive library, as the author of several books, including the classic 1872 volume History of the American Flag, and efforts to preserve the original Star-Spangled Banner. He died in 1885.

Consul McMath continued as diplomatic representative in Tangier until 1869. He returned to his native Ohio and the practice of law, and went on to serve as a judge in the court of common pleas in Cleveland. Judge McMath died in 1900. His wife and a daughter survived him.

Foreign Minister Bargash remained in his government position and waged war against European interference with and penetration into his country. In particular, he battled unfair consulate protections that gave Europeans advantages over Moroccans. In 1884, his health failed and he travelled to Europe for treatment. He died there two years later.

The reign of Sultan Muhammad IV suffered due to European influences, and unrest following a war with Spain that ended in defeat and a treaty that put a severe financial burden on Moroccans. His 14-year rule ended with his death in 1873. He was in his early forties.

Gihon’s brother, John, did not live to see his 40th birthday. His life was cut short in 1878, the victim of an illness onboard a schooner en route to New York from Venezuela, where he had been under contract to photograph gold mining operations. “Mr. Gihon was master of our art,” observed the Philadelphia Photographer, to which magazine he contributed regularly. “When Mr. Gihon became a photographer, he did not cease to be an artist, and to him as much as to any one in this country is due the elevation of photography from the mere machine routinism of a mechanical operation to the realm of art, where it properly belongs, and on which it confers so much lustre.”

Gihon’s father received a commission as surgeon of the 74th U.S. Colored Infantry during the last months of the Civil War. His adventure continued to Louisiana after the end of hostilities, and he died there in 1875.

Gihon returned to the U.S., where he reunited with Clara and met his 2-year old daughter, Charlotte. He remained in the navy after the end of the war and was assigned to stations at home and abroad. They included Nagasaki, Japan, where Gihon and the crew of their warship, the Idaho, were caught in an 1869 typhoon that wreaked havoc on the city and a host of assorted vessels in the harbor. Gihon rendered medical aid to British, French and Portuguese sailors. He received the decoration of Knight of the Military Order of Christ from the King of Portugal, and formal thanks from the other two governments.

By this time, Gihon had written a travel story, “A Look at Lisbon,” a detailed guide based on his experiences in the city during the war. The narrative appeared in the July 1866 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. He wrote another travel piece for Harper’s based on his wartime experience, the two-part “A Summer Cruise Among the Atlantic Islands” in the March and April 1877 issues. One of the illustrations depicted a man attired in the costume of a citizen of Tenerife, the largest of Spain’s Canary Islands. The face of the man in the engraving is similar in shape and facial hair to Gihon. It is possible that it was based on a photo of Gihon, perhaps one in a series of images of him in native costume that includes the carte de visite of him in Jebala garb. If the theory is true, Gihon cast himself in the role of cultural ambassador to write and illustrate his travels in the Triangle.

Gihon dedicated the vast majority of his writings to medical papers and addresses. Beginning with his 1871 Practical Suggestions in Naval Hygiene, Gihon began a steady climb to national attention as a public health reformer. He called for improved sanitary conditions, advanced medical education, and the study of demography and climatology to the betterment of healthy living. He railed against the use of tobacco and the needless loss of life due to preventable diseases.

The medical establishment honored him in 1885 with the presidency of the progressive American Academy of Medicine, a national organization that encouraged its membership to address a range of societal disorders. The military recognized his achievements with a series of plum assignments and promotions that culminated in commodore and Senior Medical Director of the Navy. He retired in 1895.

Six years later, in November 1901, Gihon suffered a paralytic stroke that effected his left side. Found in his New York City hotel room on the morning of November 14, he was carried to a hospital where he died less than two days later. He outlived daughter Charlotte, who had died in 1885. Clara and two sons, both artists in France, survived him. His remains were buried in the Gihon family plot at Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery. The grave is unmarked, which is consistent with cemetery paperwork that indicates the site “to be plain.”

Special thanks to two individuals without whom this story would not have been possible.

Brendan Mackie of Wilmington, Del., brought the Gihon images to my attention. A military veteran who served in Afghanistan, Mackie, co-authored Images of America: Fort Delaware by Arcadia Publishers.

Abdellah Ajouj generously shared his time and knowledge of Moroccan history and provided transcripts of original Arabic texts. An English professor in Morocco, he earned his MA at Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University in Fez.

References: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies; Text message exchanges with Abdellah Ajouj and Brendan Mackie; Sherman, ed., Fifty Years of Masonry in California; Gihon, Geary and Kansas; Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pa.), Feb. 9, 1875; Philadelphia Inquirer, July 31, 1868; “The Surgeon-Generalship of the United States Navy.” Universal Medical Journal 1 (1893); 1850 U.S. Census; John S. Campfield military service record, National Archives; Watson, ed., Physicians and Surgeons of America; Message to the Two Houses of Congress, Third Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress, Vol. 1; Cadiz Sentinel (Cadiz, Ohio), Feb. 26, 1862; Message to the Two Houses of Congress, First Session of the Thirty-Eighth Congress, Part II; El Fasi, City of Rabat and Its Dignitaries in the 19th and Early 20th Century, 1830-1912; Bookin-Weiner and El Mansour, eds., The Atlantic Connection; Philadelphia Photographer, September 1878; Peitzman, Steven J. “Forgotten Reformers.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine Vol. 58, No. 4 (Winter 1984); Albert L. Gihon pension record, National Archives; Laurel Hill Cemetery records courtesy of Brendan Mackie.

Ronald S. Coddington is Editor and Publisher of MI.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.