By Mike Fitzpatrick

Jacob Roemer suffered seven wounds and injuries in the line of duty during more than three years of active service. The number perhaps comes as no surprise, considering the extreme amount of frontline fighting he experienced as an artillery captain in the Army of the Potomac.

Roemer was also something of a tactical genius. His knack for improvisation, quick thinking and bold action in the face of adversity belied his lack of a formal military education.

The captain had flirted with the military long before the Civil War. Back in his native Hessen-Darmstadt, he had completed a shoemaker’s apprenticeship and went to work at his trade in Worms. In 1838, when he was 20, Roemer abruptly changed course and enlisted in the Prussian army. A horse lover, he looked forward to a cavalryman’s life and promotion. His tenure ended after less than a year when his older sister, who did not approve of his decision to join the military, legally purchased his discharge.

Roemer left Prussia to tour the world. He landed in New York City, where he went to work as a shoemaker in Flushing, married fellow German immigrant Sybiella Mauer and started a family that grew to include seven children. In 1845, he joined a local militia company, the Light Horse Artillery. According to one newspaper report, the company impressed crowds who gathered in June 1847 to watch a two-mile long martial parade to honor visiting President James K. Polk. The artillerymen, “their brave guns flashing back the sunbeams, so bright and polished did they appear, those fearful messengers of destruction to the foes of our country.”

The foes in this case were in Mexico, where war with the U.S. was in progress. No one could have imagined that a rebellion and a civil war lay on the horizon.

When the Civil War came in 1861, Roemer served as first lieutenant of the Light Horsemen. After President Abraham Lincoln called for troops to put down the rebellion, Roemer and his comrades enlisted as Battery L of the 2nd New York Light Artillery.

The battery mustered into federal service in October 1861 and soon reported for duty to the Military District of Washington, D.C. It received a compliment of six 3-inch ordnance rifles, which, with a powder charge of one pound, could send a 10-pound shot 3 1/2 miles. In capable hands, the wrought iron rifle was deadly accurate at any distance under a mile.

In May 1862, Roemer advanced to captain and battery commander. A few months later, as Confederates launched offensive operations into Northern Virginia, the battery fired its first shots in hostility at the August 9 Battle of Cedar Mountain.

First Blood

A few weeks later, the battery participated in some of the thickest of the fighting at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Early on the first day, Roemer’s five guns ripped into charging Confederates with double canister and succeeded in breaking up the assault. Later, Roemer changed his position to counter enemy battery fire. With judicial placement and handling of three of his fieldpieces, Roemer drove off 10 enemy guns. At some point during the day’s action, an enemy blast knocked Roemer down, and caused deafness in his left ear. He continued on without pause.

Fighting continued the next day, during which exploding shell fragments hit Roemer and his horse. Roemer suffered a wound in his right thigh. He had it bandaged and continued the fight until the battery expended 1,217 rounds of ammunition.

Though the battle had ended, the pain in his leg only increased. By the Battle of Antietam a couple of weeks later, the leg bothered him considerably. He later said, “I suffered so much, that I wished a bullet would hit me and end it all.” Fortunately, he and his gunners were lightly engaged. After examining the swollen, discolored leg, one surgeon asked, “How under heaven, could you ride a horse with a leg like that?” He then ordered Roemer to his tent for four weeks with the proviso, “If you come out before that time is up, I will have you court martialed for neglecting yourself.” Twenty-one days passed before Roemer could use his leg again.

Freak Accidents

Roemer suffered two freak accidents in the months after he returned to duty. Both events reveal how dangerous daily life might be for a soldier.

The first accident occurred in February 1863, when Roemer received orders to embark at Aquia Creek in Virginia. “Loading a battery on canal boats is somewhat of a task. Some fifteen cannon-carriages, caissons, battery wagon, forge, ammunition and baggage wagons, seventy-eight horses and ten mules, had to be transferred from the shore to the boats,” Roemer explained. During the onboarding a horse broke free. The frightened animal plunged backwards into the hold and crushed Roemer against a partition. The accident left him with severe bruises and “frightful gashes in his flesh.”

A second accident occurred in mid-1863 along the Mississippi River at the end of a long journey from the East. While disembarking from the steamer Marion near Vicksburg on June 18, horses, mules, cannon and other equipment moved across a long gangplank. It began to give way from the weight of one of the guns and the soft earth below. Roemer and several of his men rushed to support the gangplank using their sheer physical strength. One man had his foot caught under the bridge as it settled into the ground. Roemer’s right hand was crushed, and the third finger cut and wrenched out of its socket.

Roemer avoided injury through the rest of the year despite his participation in the sieges of Vicksburg and Jackson, and operations around Knoxville, before returning to the East with the battery.

High Marks for the “Old Rat”

In January 1864, almost every artilleryman in Roemer’s command reenlisted prior to the expiration of their original 3-year term—69 of 71 men. In appreciation of their service, Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero gave a speech complimentary to the battery in which he “commented on the superior marksmanship of its gunners, the accuracy of their aim, and its superiority in maneuvers on the battlefield.” About this time, military authorities detached Roemer and his command from the 2nd and designated it as the 34th Independent Battery, New York Light Artillery.

The Overland Campaign launched in the spring by Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant advanced the Army of the Potomac to the gates of Richmond over some of the most hotly contested ground of the war.

“Roemer’s Veteran Battery has signalized itself again.”

The veteran captain survived unscathed through The Wilderness in early May, as he and his battery covered infantry movements and turned back one Confederate assault. Soon after, at Spotsylvania Court House, the battery again showed it mettle. Fighting with only four of his six guns, two having been detached to another part of the battlefield, Roemer and his New Yorkers faced off against 10 rebel fieldpieces. Three spent bullets struck Roemer, one of which hit his field glasses and nearly threw him out of the saddle. Yet, Roemer succeeded in driving off the enemy guns before being ordered to relocate. He set up his four guns on a knoll just as the Confederates unleashed a mass infantry charge. Roemer claimed, “In this my 4 Pieces did great service.” His division commander, Brig. Gen. Orlando B. Willcox, proclaimed, “Roemer’s Veteran Battery has signalized itself again.”

Two weeks later during the heavy fighting at Cold Harbor, flying iron hit him in the head and knocked him momentarily senseless. He was struck “an inch above the right eye making a deep cut to the skull and tearing the eyebrow.” In typical Roemer fashion, he continued on, and even coordinated movements between his batteries and two others, the 14th Massachusetts and 7th Maine artilleries.

Still on his feet in the chaos and confusion of battle, Roemer conducted a maneuver that earned him high marks from his superiors. The event came when he recognized a rebel artillery barrage as an attempt to soften Union defenses prior to an infantry charge. Roemer reacted by ordering his men to gradually cease firing and lie down. The Confederates assumed the barrage had been successful—but learned the truth when the infantry stepped out of nearby woods and into the range of Roemer’s battery and those from Massachusetts and Maine. On Roemer’s command the federal fieldpieces—14 total—fired five volleys in unison. As the surprised rebels retreated to the woods, Roemer had the guns fire once more by battery. He noted that the volley “drove them back faster than at the double quick.” Brig. Gen. Willcox declared, “Roemer, you old rat, this is the best trick you played yet.”

The “old rat” had another trick up his sleeve. A few days after Cold Harbor, Roemer devised an innovative solution to lob shells over a hill and into an enemy camp located behind it. He buried the tail end of one of his guns far enough into the ground to give the cannon an elevation of about 45 degrees. This move, along with a reduced powder charge, succeeded in dropping percussion shells over the hill and into the camp, successfully driving the enemy from their quarters. Roemer had, in fact, improvised a mortar out of a rifled gun.

A Lapse of Judgment

Roemer’s clever tactical move at Cold Harbor in June was followed by a singular lapse of judgment that almost cost him his career.

On July 3, 1864, along the Petersburg front, he visited the quarters of his artillery chief, Lt. Col. J. Albert Monroe, bearing a request. Roemer presented Monroe with an application from a Mr. Budenbender for the sutlership of the Ninth Corps artillery. Roemer endorsed Budenbender as a friend and a good man. He did not mention that Budenbender was his wife’s brother-in-law. When Monroe explained that he had received several applications for the position and that a decision would have to wait, Roemer offered him a hundred dollar bill to cover expenses. Monroe declined, and reported Roemer for attempted bribery. The complaint made it up the chain of command to Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, commander of the Ninth Corps. He referred the case to a Military Board, which replied to Burnside with a recommendation for courts martial.

Burnside opted not to send Roemer before judge and jury. Instead, he referred the case to Brig. Gen. Willcox with a recommendation that Willcox read the Military Board’s findings to Roemer, and inform him of Burnside’s “deep regret that charges so grave should have been brought against an officer in whom he has always entertained so much confidence and whose actions in the field have always merited his highest approval and he cannot but feel convinced that Capt. Roemer committed this act under some momentary aberration of mind which was totally at variance with his real character and that in view of his long and valuable services he is willing to pass over this offense provided Capt. Roemer on cool reflection expresses himself to be convinced of the wrong nature of the transaction and his determination that no such act shall tarnish his military history in the future.”

Willcox obeyed orders and determined that Roemer was sufficiently embarrassed and sorry for his actions. Roemer escaped with only a figurative slap on the wrist.

The Red-Whiskered Battery

While the bribery drama played out at headquarters, Roemer suffered another slight wound in the field. This time, a rebel bullet struck him just below the left knee in front of Petersburg on July 9, 1864. The injury did not prevent him from improvising “fire shells” to successfully ignite farm buildings occupied by Confederate sharpshooters. Willcox praised him yet again for his valuable service.

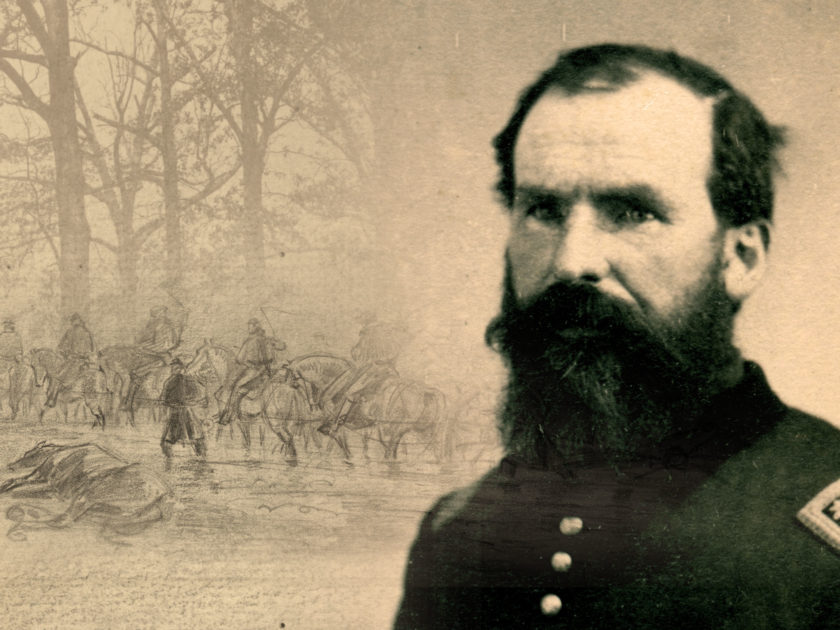

Roemer received more notice about this time from an unexpected source—Confederate gunners manning a battery opposite his own. One of these rebels called out, “Where the devil did that red-whiskered battery come from?” The reference was to Roemer’s thick, ruddy beard.

The battery received orders to pull out of line in August 1864 and move to the Weldon Railroad. Once there, the men erected earthworks under Roemer’s supervision. During the construction, he suffered another freak accident when an ax slipped from a soldier’s grip. The blade caught Roemer in the left kneecap—the second time in two months that the leg had been damaged. The ax also clipped his hand and nearly severed a finger.

His leg became infected and swelled to extreme proportions. Surgeons suggested an amputation, but Roemer refused, despite efforts of Brig. Gen. Willcox and three doctors to convince him otherwise. They told him “I could not possibly live if I insisted on not having it taken off, as mortification had already set in and my time to live was limited to three days. I said that I preferred to die with my leg if I only had three days to live, rather than have it amputated.”

Roemer’s strong constitution ultimately triumphed. Much to the surprise of his comrades, his leg began to heal and he kept it.

Under Fire One More Time

The year 1865 began on a peaceful note when Roemer requested a furlough to go home on recruiting duty. Back in Flushing, he spent time with his wife and children. He also sat for his carte de visite wearing the shoulder straps of a major. Roemer had recently received the brevet rank for gallantry during Spotsylvania and the Richmond Campaign.

By the end of February, he rejoined his battery at Petersburg. Roemer returned to a relative quiet as soldiers on both sides had hunkered down for the winter.

Everything changed on March 24 when Roemer’s Battery received orders to take up a new position at Fort McGilvery, near the far right of the Union siege lines, about a quarter mile south of the Appomattox River. At approximately 3:30 a.m. the following morning, the sergeant of the guard awoke Roemer, saying, “Captain, there is some disturbance on our left in the direction of Fort Stedman, but I cannot make out what it is.”

Roemer soon found out. Arising in the full dark of night, he heard musket fire at the beginning of a massive pre-dawn attack by nearly a third of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army. The desperate rebels were attempting a breakout through the heavily fortified Union lines that had a choke hold on the Confederate capital.

The firing continued as a half hour passed. The flash of one of Stedman’s guns towards the rear alerted Roemer that the rebels had taken the fort and turned captured artillery on retreating Federals. Roemer responded by shifting three of his guns to embrasures on the left of Fort McGilvery. In the dawn’s early light, Roemer’s Battery fired some 30 shots at Stedman before other Union guns went into action.

Rebel cannon and mortar gunners trained their pieces on Fort McGilvery, their next target. “They had full sweep upon us, and the air was filled with flying shot and shell,” observed Roemer. A column of gray infantry accompanied the artillery barrage, and surged past Fort Stedman into the Union rear.

The rebels advanced through a deep road cut towards the rear of Fort McGilvery. If the Confederates captured McGilvery and silenced Roemer’s Battery, they would control a major road that led to Lt. Gen. Grant’s critical supply base at City Point. Unfortunately, the parapet along the back of the fort lacked embrasures, or openings, for cannons and no guns could be brought to bear on this threat. Roemer moved quickly to check the rebel onslaught. He ordered one of his guns pushed up to the top of the rear parapet. Ten men leapt into action and somehow wrestled the cannon into position.

“The situation was very critical,” Roemer recounted. “There, in our left rear, was the advancing rebel column; here, on the rear parapet of Fort McGilvery, were we with but one gun bearing upon the column. But as this column was very compact in the cut, we felt we could do pretty good execution. I set to work with this one gun and nine men to do all that could be done.”

The first three shots went high. “We must do better or we are gone,” Roemer shouted. He personally sighted the fourth shot to get the range correctly. The next four shells went just where he wanted them. They struck the ground about four yards in front of the column, exploding right in the faces of the leading Confederates.

As this action occurred, enemy artillery pounded away at the front of Fort McGilvery. With Roemer’s lone rear-firing gun sitting fully exposed on the top of the earthworks, it was only a matter of time before one of the incoming missiles found its mark. Just as Roemer was about to fire the ninth round, a Confederate shell exploded in the midst of the crew. John Bauer, the number 3 man of the gun squad, was nearly cut in two and killed instantly. Three or four other cannoneers suffered wounds. A piece of the exploding shell caught Roemer on the right shoulder and hurled him off the parapet. He tumbled about 10 feet to the ground below.

Capt. Henry Dreyer of the 46th New York Infantry reached the fallen major first. “I was the first man to lift his head from the ground, the blood was issuing from his nose and mouth when I raised him to a sitting position.” Sgt. Albert Townsend, one of the survivors of the shattered gun crew, arrived at Roemer’s side. He recalled that “Capt. Dreyer and myself picked him up unconscious bleeding from the mouth and nose.”

Though the shell fragments had taken out Roemer and most of the gun crew, three survivors managed to fire 11 more rounds before the Confederates surrendered. By 8 a.m., Union troops had recaptured Fort Stedman. In his after action report, Brig. Gen. Willcox stated, “This attack was handsomely repulsed by my skirmishers and troops of the Second Brigade in Battery No. 9, assisted by the artillery, particularly one piece of Roemer’s battery, under Major Roemer himself.”

“I was the first man to lift his head from the ground, the blood was issuing from his nose and mouth when I raised him to a sitting position.”

Roemer received prompt attention to determine the nature of his injuries. Capt. Dreyer explained, “His Surgeon and the Colonel of my Regiment were soon at hand and, consciousness restored, the Surgeon examined him and found that he had received a severe contusion on the right shoulder, collar bone & neck was internally injured, and had also injured his left leg, so that he could not walk nor use his right arm.”

The medical director of the Ninth Corps, Surg. John McDonald, laid Roemer on a blanket and diagnosed him with a paralyzed arm, a badly wrenched left leg, a probable rupture and a host of severe injuries across his entire body. Hardly knowing where to begin treatment, the doctor administered morphine. Later that evening, personnel stripped off Roemer’s uniform and conducted another examination of his blackened and bruised body. He remained on morphine for several days.

Surgeon McDonald proclaimed, “Roemer had received more knocking and banging than any one Officer in the 9th Corps and yet lives; he has an iron constitution.”

Epilogue

Roemer regained his strength as the Confederacy weakened. On April 2, just eight days after the rigorous defense of Fort McGilvery, the Confederates abandoned Petersburg and Richmond under the intense Union artillery bombardment. The firing continued until about 3 a.m. on April 3, when it became clear the rebels had evacuated. Roemer, back on his feet but far from recovered, gave his battery the order to cease fire. A live round remained in one of the cannon. Roemer noted, “This gun was fired, and that was the last one fired into Petersburg, and was also, for the 34th New York Battery, the last shot of the war. I looked at my watch and noted the time; it was 3:40 a.m. As the echoes of this last shot died away, I shouted, ‘Petersburg is ours; the war is over; and today is my 47th birthday. Boys you have done nobly.’”

Roemer and the stalwart survivors of the battery mustered out of the army on June 21, 1865, at Hart Island in New York Harbor. Several generals to whom he reported encouraged him to accept a captain’s commission in the regular army. Roemer politely declined, and explained he preferred active fighting to drilling. He reunited with his family in Flushing and returned to shoe manufacturing.

Roemer died in 1896 at age 78. He left an unfinished manuscript of his life and military services. With the assistance of an editor and funding from his estate, Roemer’s Reminiscences of the War of the Rebellion 1861-1865 was published in 1897. Much of this story is drawn from his account, with additional material taken from his military and pension records.

Mike Fitzpatrick has been an avid photo collector for 30 years. He has authored several magazine articles and written a Civil War novel, The Letters From Fiddler’s Green. He is currently writing a history of Annapolis, Md., during the Civil War.

SPREAD THE WORD: We encourage you to share this story on social media and elsewhere to educate and raise awareness. If you wish to use any image on this page for another purpose, please request permission.

LEARN MORE about Military Images, America’s only magazine dedicated to showcasing, interpreting and preserving Civil War portrait photography.

VISIT OUR STORE to subscribe, renew a subscription, and more.